Rapid Health Impact of the Avenue Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Five Pits Trail

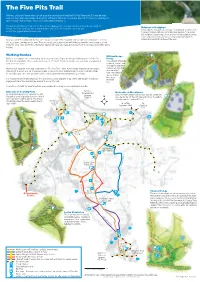

The Five Pits Trail Walkers, cyclists and horse riders can all enjoy the countryside of the Five Pits Trail. Follow the 5.5 mile off-road surfaced route from Grassmoor Country Park to Tibshelf Ponds or extend your route to 7.5 miles by exploring the route through Williamthorpe Ponds and Holmewood Woodlands. The trail mostly follows the route of the Great Central Railway. Since the large collieries and smaller pits along the railway closed, the landscape has changed dramatically. Parts of the land were opencast and Holmewood Sculpture Funded by the Young Roots Heritage Lottery Fund, students from most of the original railway line removed. Deincourt School worked with artists from Gotham-D to design this sculpture. Using metal, stone and wood, the sculpture shows leaves and keys (seeds) and takes its inspiration from both the Now you will find a rolling trail that has some long steep slopes. This may limit some people's access in places - look for natural and industrial heritage of the area. the 'steep slope' symbols on the map. There are no stiles or steps and you will find seats along the way to stop, rest and enjoy the views. Look out for the information boards with large site maps showing some of the heritage and wildlife along the trail. Mansfield Road Walking Routes Williamthorpe Walkers can explore the surrounding landscape on Public Rights of Way by following one of the Five Ponds Pits Trail Circular Walks. These walks are between 2.5 and 5.5 miles in length and each walk is waymarked This network of ponds, with a coloured disc. -

Bolsover, North East Derbyshire & Chesterfield

‘extremewheels roadshows’ Summer 2017 BOLSOVER, NORTH EAST DERBYSHIRE & CHESTERFIELD JULY 15th Chesterfield - Stand Rd Rec Ground 1 - 3pm 15th Tupton - Rugby Club 1 - 3pm 24th Hasland - Eastwood Park 1 - 3pm 15th Chesterfield - Queens Park 6 - 8pm 25th Chesterfield - Stand Rd Rec Ground 1 - 3pm 15th Mickley - Community Hut 6 - 8pm 25th Tupton - Rugby Club 1 - 3pm 16th Hasland - Eastwood Park 1 - 3pm 25th Chesterfield - Queens Park 6 - 8pm 17th Whitwell - Skatepark 1 - 3pm 25th Mickley - Community Hut 6 - 8pm 17th Grassmoor - Barnes Park 1 - 3pm 27th Whitwell - Skatepark 1 - 3pm 17th Hasland - Eastwood Park 6 - 8pm 27th Grassmoor - Barnes Park 1 - 3pm 18th Bolsover - Hornscroft Park 6 - 8pm 27th Hasland - Eastwood Park 6 - 8pm 18th Shirebrook - Skatepark 6 - 8pm 28th Bolsover - Hornscroft Park 6 - 8pm 22nd Chesterfield - Stand Rd Rec Ground 1 - 3pm AUGUST 22nd Tupton - Rugby Club 1 - 3pm 1st Chesterfield - Stand Rd Rec Ground 1 - 3pm 22nd Chesterfield - Queens Park 6 - 8pm 1st Tupton - Rugby Club 1 - 3pm 22nd Mickley - Community Hut 6 - 8pm 1st Chesterfield - Queens Park 6 - 8pm 24th Whitwell - Skatepark 1 - 3pm 1st Mickley - Community Hut 6 - 8pm 24th Hasland - Eastwood Park 6 - 8pm 2nd Hasland - Eastwood Park 1 - 3pm 25th Bolsover - Hornscroft Park 6 - 8pm 2nd Pilsley - Skatepark 6 - 8pm 25th Shirebrook - Skatepark 6 - 8pm 3rd Whitwell - Skatepark 1 - 3pm 29th Chesterfield - Stand Rd Rec Ground 1 - 3pm 3rd Grassmoor - Barnes Park 1 - 3pm 29th Tupton - Rugby Club 1 - 3pm 3rd Hasland - Eastwood Park 6 - 8pm 29th Chesterfield - Queens Park -

Rapid Health Impact Assessment of the Avenue Development August 2016

Rapid Health Impact Assessment of the Avenue development August 2016 Author Richard Keeton, Public Health Manager, Derbyshire County Council Contributors Steering group members Julie Hirst, Public Health Principal, Derbyshire County Council Mandy Chambers, Public Health Principal, Derbyshire County Council Jim Seymour, Transport Strategy Manager, Derbyshire County Council Alan Marsden, Project Officer - Transportation Projects, Derbyshire County Council Tamsin Hart, Senior Area Manager, Homes & Communities Agency Martyn Handley, Economic Development Projects Officer, North East Derbyshire District Council Sean Johnson, Public Health, Lincolnshire County Council Steve Buffery, Derbyshire County Council Andrew Grayson, Chesterfield Borough Council Community consultation leads Susan Piredda, Public Health Development Worker, Derbyshire County Council Louise Hall, Public Health Development Worker, Derbyshire County Council Fiona Unwin, Public Health Development Worker, Derbyshire County Council Lianne Barnes, Public Health Development Worker, Derbyshire County Council Appraisal panel members Joe Battye, Derbyshire County Council Councillor Allen, Cabinet Member, Health and Communities (Public Health), Derbyshire County Council Neil Johnson, Economic Growth and Regeneration Lead, Chesterfield Borough Council Allison Westray-Chapman, Joint Assistant Director Economic Growth, Bolsover District Council & North East Derbyshire District Council Steve Brunt, Assistant Director Streetscene, Bolsover District Council & North East Derbyshire District -

EAST MIDLANDS REGION - Wednesday 8 June 2016

MINUTES OF THE DECISIONS OF THE COMMISSION ON THE INITIAL PROPOSALS FOR THE EAST MIDLANDS REGION - Wednesday 8 June 2016 Session 1: Wednesday 8 June 2016 Present: David Elvin QC, Commissioner Neil Pringle, Commissioner Sam Hartley, Secretary to the Commission Tony Bellringer, Deputy Secretary to the Commission Tim Bowden, Head of Reviews Glenn Reed, Review Manager Sam Amponsah, Review Officer Mr Reed and Mr Amponsah presented the Secretariat's schemes to Commissioners. Lincolnshire The Commissioners considered that, due to its almost whole allocation of constituencies with a Theoretical Entitlement (TE) to 6.97 constituencies, Lincolnshire could be treated on its own and should continue to be allocated seven constituencies. Commissioners considered that the two constituencies of Gainsborough, and South Holland and the Deepings could remain wholly unchanged, while Grantham and Stamford CC, and Louth and Horncastle CC would be changed following changes to local government ward boundaries. The electorate of the existing Sleaford and North Hykeham CC constituency was too large at 86,652, while that of its neighbouring constituencies of Lincoln BC (at 67,115) and Boston and Skegness CC (66,250) were too small. Commissioners therefore agreed that the five wards comprising the town of North Hykeham, and the Waddington West ward be included in the new Lincoln constituency, which in turn loses the Bracebridge Heath and Waddington East ward to the Sleaford constituency. It would not be possible to retain this ward in the Lincoln constituency without dividing the town of North Hykeham. In order to further reduce the electorate of the existing Sleaford and North Hykeham constituency, and to increase that of Boston and Skegness, Commissioners also agreed the transfer of the additional two wards of Kirkby la Thorpe and South Kyme, and Heckington Rural from the existing Sleaford constituency. -

51 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

51 bus time schedule & line map 51 Chesterƒeld - Danesmoor View In Website Mode The 51 bus line (Chesterƒeld - Danesmoor) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chesterƒeld: 5:44 AM - 10:30 PM (2) Clay Cross: 11:54 PM (3) Danesmoor: 5:23 AM - 8:45 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 51 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 51 bus arriving. Direction: Chesterƒeld 51 bus Time Schedule 48 stops Chesterƒeld Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:58 AM - 11:00 PM Monday 5:44 AM - 10:30 PM Cemetery, Danesmoor Tuesday 5:44 AM - 10:30 PM Linden Avenue, Danesmoor Kenmere Close, Clay Cross Civil Parish Wednesday 5:44 AM - 10:30 PM Springvale Road Allotments, Danesmoor Thursday 5:44 AM - 10:30 PM Friday 5:44 AM - 10:30 PM Beresford Close, Danesmoor Springvale Road, Clay Cross Civil Parish Saturday 6:13 AM - 10:30 PM Penistone Gardens, Danesmoor Penistone Gardens, Clay Cross Civil Parish Springvale Close, Danesmoor 51 bus Info Dunvegan Avenue, Clay Cross Civil Parish Direction: Chesterƒeld Stops: 48 Gentshill, Danesmoor Trip Duration: 41 min Line Summary: Cemetery, Danesmoor, Linden 75 Cemetery Road, Danesmoor Avenue, Danesmoor, Springvale Road Allotments, Danesmoor, Beresford Close, Danesmoor, Penistone Pilsley Road, Danesmoor Gardens, Danesmoor, Springvale Close, Danesmoor, Gentshill, Danesmoor, 75 Cemetery Road, Bertrand Avenue, Clay Cross Danesmoor, Pilsley Road, Danesmoor, Bertrand Avenue, Clay Cross, Commonpiece Road, Clay Cross, Commonpiece Road, Clay Cross Broadleys, Clay Cross, Bus Station, -

Page 1 of 13 Wingerworth Parish Council Clerk: Charlotte Taylor 36

Wingerworth Parish Council Clerk: Charlotte Taylor 36 Hawksley Avenue Chesterfield S40 4TW 25 June 2019 Dear Councillor Notice of meeting of the Meeting of the Parish Council on Wednesday 3 July 2019 – 7:00pm at the Parish Hall. You are summoned to the next meeting of the Council which will take place as detailed above. The agenda and supporting papers for this meeting are attached. The minutes are enclosed. In the event that you are unable to attend you should inform me in advance of the meeting so that I am able to record your apologies. Yours faithfully Charlotte Taylor Clerk to the Council Page 1 of 13 Wingerworth Parish Council – Meeting of the Council on Wednesday 3 July 2019. 1. Apologies for absence 2. Variation of order of business 3. Declaration of interests 4. Public forum 5. Confirmation of previous minutes 6. Chair’s announcements 7. Review of Action Plan 8. Correspondence received 9. Clerk’s report – information 9.1. Correction to August 2018 payments 9.2. HS2 Phase 2b - Design Refinement Consultation (circulated) 9.3. Confirmation of 2019-20 Council meeting dates 9.4. Session with Bowls Club booked for Sunday 21 July at 1:30pm 9.5. DCC Smoke Free Spaces Consultation (circulated) 9.6. List of upcoming community events for NEDDC Digital Media Officer 10. Clerk’s report – decisions 10.1. Request to carry out work on tennis club edging: quote pending 10.2. Request to carry out additional works at Island Pond to treat bulrushes: £825.00 10.3. Review of Complaints Policy 10.4. -

North East Derbyshire District Council Planning Policy Team 2013 Mill Lane Wingerworth Chesterfield S42 6NG SENT by E-MAIL ONLY

North East Derbyshire District Council Planning Policy Team 2013 Mill Lane Wingerworth Chesterfield S42 6NG SENT BY E-MAIL ONLY TO [email protected] 23 June 2020 Dear Sir / Madam NORTH EAST DERBYSHIRE LOCAL PLAN EXAMINATION – COMMENTS ON HOUSING LAND SUPPLY (HLS) EVIDENCE Thank you for consulting with the Home Builders Federation (HBF) as a participant of North East Derbyshire Local Plan Examination Matter 11 Hearing Session. The HBF is the principal representative body of the house-building industry in England and Wales. Our representations reflect the views of our membership, which includes multi-national PLC’s, regional developers and small, local builders. In any one year, our members account for over 80% of all new “for sale” market housing built in England and Wales as well as a large proportion of newly built affordable housing. We would like to submit the following representations. The Council has provided up dated evidence in the following documents :- • ED95 Five Year Housing Land Supply (5 YHLS) Statement (at adoption), April 2019 ; • ED96 Schedule of Completions 2018/19 ; • ED97 Schedule of Commitments at 31st March 2019 ; • ED98 Rolling 5 YHLS Table, April 2019 ; and • ED99 Housing Trajectory for Plan Period, April 2019. In ED95, the Council’s 5 YHLS position between 2019/20 – 2024/25 is stated as 6.32 years. In this calculation, housing need is 1,827 dwellings (365.4 dwellings per annum) based on :- • housing requirement of 330 dwellings per annum (using standard methodology LHN figure) x 5 years ; • +90 dwellings shortfall up to 2019/20 ; • 5% buffer (as determined by 2019 Housing Delivery Test results). -

Agenda, Parish Council, 2020-12-10

Wingerworth Parish Council Clerk: Charlotte Taylor 42 Hawksley Avenue Chesterfield S40 4TN 3 December 2020 Dear Councillor Notice of meeting of the Meeting of the Parish Council on Thursday 10 December 2020 – 7:00pm via Zoom (the link and code will be forwarded via email). You are summoned to the next meeting of the Council which will take place as detailed above. The agenda and supporting papers for this meeting are attached. The minutes are enclosed. In the event that you are unable to attend you should inform me in advance of the meeting with the reasons for tendering your apologies, so that I am able to record your apologies. Yours faithfully Charlotte Taylor Clerk to the Council Page 1 of 12 Agenda – Meeting of the Council on Thursday 10 December 2020 1. Apologies for absence ................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Variation of order of business.................................................................................................................... 3 3. Declaration of interests ............................................................................................................................. 3 4. Public forum ............................................................................................................................................... 3 5. Confirmation of previous minutes ............................................................................................................. 3 6. Chair’s announcements -

Available Property 15

Available Property 13/09/2017 to 19/09/2017 15 Properties Listed Bid online at www.rykneldhomes.org.uk 01246 217670 Properties available from 13/09/2017 to 19/09/2017 Page: 1 of 6 Address: Churchside, Calow, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S44 5BH Ref: 1004622 Type: 2 Bed Bungalow Rent: £ 90.21 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Address: Cemetery Road, Clay Cross, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S45 9RS Ref: 1009581 Type: 2 Bed House Rent: £ 87.26 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Address: Penncroft Lane, Clay Cross, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S45 9HN Ref: 1020037 Type: 1 Bed Bungalow Rent: £ 84.20 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Properties available from 13/09/2017 to 19/09/2017 Page: 2 of 6 Address: Stonelow Green, Dronfield, Derbyshire S18 2ET Ref: 1034555 Type: 2 Bed Flat Rent: £ 87.26 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Address: Berry Avenue, Eckington, Derbyshire S21 4AR Ref: 1040068 Type: 1 Bed Bungalow Rent: £ 82.74 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Address: William Street, Eckington, Derbyshire S21 4GD Ref: 1051156 Type: 3 Bed House Rent: £ 95.63 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Properties available from 13/09/2017 to 19/09/2017 Page: 3 of 6 Address: Mill Lane, Grassmoor, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S42 5AA Ref: 1062380 Type: 2 Bed House Rent: £ 84.35 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Address: Whitmore Avenue, Grassmoor, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S42 5AE Ref: 1065447 Type: 3 Bed House Rent: £ 85.39 per week Landlord: Rykneld Homes Address: Beech Crescent, Killamarsh, Derbyshire S21 1AE Ref: 1077185 Type: 1 Bed Flat Rent: £ 78.08 per week Landlord: Rykneld -

Official Opening New Building Chesterfield School

Derbyshire County Council _________ The Excepted District of the Borough of Chesterfield. _________ CHESTERFIELD BOROUGH Founded 1594 EDUCATION COMMITTEE OFFICIAL OPENING of the NEW BUILDING for CHESTERFIELD SCHOOL by Sir Philip B. Dingle, C.B.E., LL.D. Thursday, 19th October, 1967 DERBYSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL ____________ THE EXCEPTED DISTRICT OF THE BOROUGH OF CHESTERFIELD ____________ The Worshipful The Mayor COUNCILLOR G. A. WIGFIELD, J.P. The Chairman of the Borough Education Committee ALDERMAN E. SWALE, C.B.E., D.F.C., J.P. Vice-Chairman of the Borough Education Committee ALDERMAN H. C. MARTIN Town Clerk: Borough Education Officer: R. A. KENNEDY B. MATTHEWS, B.Sc. Headmaster: W. E. GLISTER, M.A., J.P. P R O G R A M M E ___________ 1. Alderman E. Swale, C.B.E., D.F.C.. J.P., Chairman of the Borough Education Committee and Chesterfield School Governors, will preside. 2. The Borough Education Ofiicer will explain the purpose of the school. 3. The Chairman will welcome Sir Philip Dingle and invite him to open the school. 4. Opening by Sir Philip B. Dingle. C.B.E., LL.D. At the conclusion of his address, Sir Philip Dingle will be invited to unveil the commemorative plaque in the entrance hall. The audience is asked to remain in-the hall during this period and it is hoped that the unveiling will be seen in the hall by means of closed circuit television. 5. The Chairman of the County Education Committee, Alderman J. W. Trippett, LL.B., will propose a vote of thanks to Sir Philip Dingle, which will be seconded by Councillor V. -

Land at Blacksmith's Arms

Land off North Road, Glossop Education Impact Assessment Report v1-4 (Initial Research Feedback) for Gladman Developments 12th June 2013 Report by Oliver Nicholson EPDS Consultants Conifers House Blounts Court Road Peppard Common Henley-on-Thames RG9 5HB 0118 978 0091 www.epds-consultants.co.uk 1. Introduction 1.1.1. EPDS Consultants has been asked to consider the proposed development for its likely impact on schools in the local area. 1.2. Report Purpose & Scope 1.2.1. The purpose of this report is to act as a principle point of reference for future discussions with the relevant local authority to assist in the negotiation of potential education-specific Section 106 agreements pertaining to this site. This initial report includes an analysis of the development with regards to its likely impact on local primary and secondary school places. 1.3. Intended Audience 1.3.1. The intended audience is the client, Gladman Developments, and may be shared with other interested parties, such as the local authority(ies) and schools in the area local to the proposed development. 1.4. Research Sources 1.4.1. The contents of this initial report are based on publicly available information, including relevant data from central government and the local authority. 1.5. Further Research & Analysis 1.5.1. Further research may be conducted after this initial report, if required by the client, to include a deeper analysis of the local position regarding education provision. This activity may include negotiation with the relevant local authority and the possible submission of Freedom of Information requests if required. -

Hunloke Park Primary School, Dear Parents/Carers Our Week Ahead

Hunloke Park Primary School, Lodge Drive, Wingerworth, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S42 6PT Tel. 01246 276831 Head teacher: Ms J. Cadman Deputy Headteacher: Mrs J Murphy 11th September 2017 Dear Parents/Carers Year 6 transition to Secondary School Applications for Secondary School are now open and should be completed by 31st October 2017. The easiest way to apply for a school place is online at www.derbyshire.gov.uk/admissions. If you would like more details call 01629 533190 or visit the website, it might also a good idea to attend some of our local secondary schools’ open evenings – details are as follows: Tupton Hall School – Thursday 14 September - 5.30 pm to 7.30 pm Whittington Green School – Tuesday 19 September – 5.00 pm to 7.00 pm Brookfield Community School – Wednesday 20 September - 7.00 pm to 9.00 pm Lady Manners School – Thursday 28 September – 4.00 pm to 6.30 pm Highfields School – Thursday 5 October – 2.00 pm – 4.00 pm and 6.30 pm to 8.30 pm You only make one application and you are invited to state three preferences on it. This is the only application form you need to fill in - whether you do that by phone or online. Online or phone applications will be acknowledged automatically. Year 5 Swimming The swimming programme for Year 5 begins on Monday 18th September. Year 5 children need to ensure they have their kit, 50p for a locker and a fruit snack if they wish. FLU Immunisation forms Pupils in Y1, Y2, Y3 and 4 recently received Influenza Vaccination Consent Forms from the Schools Immunisation Team.