The Bard and the Bible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AE Housman's Poetry

A.E. HOUSMAW'S POETRY: A REASSESSMENT ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of ^t)rto2!opl)p IN ENGLISH BY JALIL UDDIM AHMED Under the Supervision of Dr. Rahatullah Khan Reader DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2008 Topic : A.E. Housman's Poetry: A Reassesmant A cursory glance at the small output shows that Housman may not rank with major Victorian poets with respect to the emotional intensity and thematic variety of their verse. But he can justifiably be called a poet who communicates with utmost verbal directness. Since he has never been rated as a major figure, he has, perhaps, not received the amount of critical attention which, for example, Hopkins did. But the fact that outstanding critics like Edmund Wilson, Randall Jarrell,' William Empson, Christopher Ricks, F.W. Bateson, and Cleanth Brooks have commented on his poetry, clearly indicates that his verse has its own kind of poetic excellence. The present study entitled A.E. Housman's Poetry: A Reassessment aims at studying the major themes of Housman's poetry. Since his death in 1936 Housman's character and personality have attracted more critical attention than his poetry. Housman's poetry has often been praised by his critics for its simplicity of form and meaning. Apparently it does not seem to offer any difficulty. But there is enough truth in what J.P. Bishop has remarked about this simplicity when he says that despite an apparent clarity such that almost any poem seems ready to deliver its meaning at once, there is always something that is not clear, something not brought into the open, something that is left in doubt. -

The Military Image in the Poetry of A. E. Housman

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1970 The Military Image in the Poetry of A. E. Housman Richard Alan Hudson Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Hudson, Richard Alan, "The Military Image in the Poetry of A. E. Housman" (1970). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3782. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/3782 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MILIT MY Hl:AGE IN THE POETRY OF A. E. HOUSMAN BY RICHARD ALAN HUDSON A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts, Major in English, South Dakota State. University 1970 SO TH DAKOTA STAT,E UNIVERSITY· LIBRARY THE MILITARY IMAGE IN THE POETRY OF A. E. HOUSMAN This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investigation by a candidate for the degree, Master of Arts, and is acceptable as meeting the thesis requirements for this degree. Acceptance of this thesis does not imply that -the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. 1 (/ (/ ! hes i g'l Ad Vi s er COate 7 7 Major Adviser Date i:Jiead, English Department iii PREFACE This thesis analyzes the military image in the poems of A. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Fabian Child: English and American Literature and Socialist Reform, 1884-1915 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2q169884 Author Hollander, Amanda Farrell Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Fabian Child: English and American Literature and Socialist Reform, 1884-1915 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Amanda Farrell Hollander 2015 © Copyright by Amanda Farrell Hollander 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Fabian Child: English and American Literature and Socialist Reform, 1884-1915 by Amanda Farrell Hollander Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Joseph E. Bristow, Chair “The Fabian Child: English and American Literature and Socialist Reform, 1884-1915” intervenes in current scholarship that addresses the impact of Fabian socialism on the arts during the fin de siècle. I argue that three particular Fabian writers—Evelyn Sharp, E. Nesbit, and Jean Webster—had an indelible impact on children’s literature, directing the genre toward less morally didactic and more politically engaged discourse. Previous studies of the Fabian Society have focused on George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and Beatrice Webb and Sidney Webb to the exclusion of women authors producing fiction for child readers. After the Fabian Society’s founding in 1884, English writers Sharp and Nesbit, and American author Webster published prolifically and, in their work, direct their socialism toward a critical and deliberate reform of ii literary genres, including the fairy tale, the detective story, the boarding school novel, adventure yarns, and epistolary fiction. -

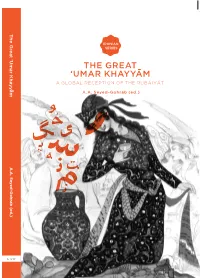

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

The Housman Society Journal Vol.43 (Dec 2017)

Volume Forty-Three 2017 Editor: David Butterfield The Housman Society Founders John Pugh and Joe Hunt President Sir Christopher Ricks, MA, BLitt., FBA Vice-Presidents Prof. Archie Burnett MA, DPhil Peter Clague MA, MBA Prof. Benjamin Franklin Fisher IV Sir Andrew Motion FRSL P.G. Naiditch MA, MLS Jim Page MBE, MA Prof. Norman Page MA, PhD, FRSCan. Sir Tom Stoppard OM, OBE Gerald Symons Chairman Peter Waine BSc. Vice-Chairman Andrew Maund MA, MPhil General Secretary Max Hunt MA, Dip.Ed. Treasurer Richard Aust OBE, M.Ed., MSc, Dip.Sp.Ed. Editor of the Journal David Butterfield MA, MPhil, PhD Editor of the Newsletter Julian Hunt FSA Committee Jane Allsopp BMus. Jennie McGregor-Smith Elizabeth Oakley MA, LRAM, Dip. RSA Pat Tansell Housman Society Journal Volume Forty-Three December 2017 The Chairman’s Notes Peter Waine 4 Chansons d’Outre-tombe Peter Sisley 9 Faith Hymns and Poetry: An Excerpt from a Lecture Timothy Dudley-Smith 46 ‘Arthur the King’ and ‘Arthur the Man’ in Clemence Housman’s The Life of Sir Aglovale De Galis Gabriel Schenk 52 The Carnage of Bebriacum Andrew Breeze 72 ‘A Distracting Entanglement’: Examining Some Assertions in Peter Parker’s Housman Country Alan James 79 ‘Yours every truly’: Signing Off with Housman David Butterfield 100 Biographies of Contributors 106 The Housman Society and Journal 108 Chairman’s Notes 2017 It has been normal practice for the Society’s Chairman to open each Journal with a retrospective of the year’s calendar of events. The election of our new Chairman, Peter Waine, was reported in the Autumn Newsletter when Max Hunt as Secretary gave his summary of the year’s programme. -

The Housman Society Journal (2018)

The Housman Society Journal Volume Forty-Four2018 Editor: Derek Littlewood The Housman Society 80 New Road Bromsgrove WorcestershireB 60 2LA England CharityNumber 100107 ISSN 0305-926X Website: http://www.housman-society.co.uk E-mail: [email protected] TheReproduced illustration by on courtesy the cover of the is Nationalfromthe drawingPortrait ofGallery, A. E. Housman London by Francis Dodd, 1926 The Housman Society Founders John Pugh and Joe Hunt President Sir Christopher Ricks, MA, BLitt., FBA Vice-Presidents Prof. Archie Burnett MA, DPhil Peter Clague MA, MBA Prof. Benjamin Franklin Fisher IV Sir Andrew Motion FRSL P.G. Naiditch MA, MLS Jim Page MBE, MA Prof. Norman Page MA, PhD, FRSCan. Sir Tom Stoppard OM, OBE Gerald Symons Chairman Peter Waine BSc. Vice-Chairman Andrew Maund MA, MPhil General Secretary Max Hunt MA, Dip.Ed. Treasurer Richard Aust OBE, M.Ed., MSc, Dip.Sp.Ed. Editor of the Journal Derek Littlewood BA, MA, PhD Editor of the Newsletter Julian Hunt FSA Committee Jane Allsopp BMus. Jennie McGregor-Smith Jo Slade BA (Hons) Econ. Pat Tansell Housman Society Journal Volume Forty-Four December 2018 Laurence Housman as Literary Executor Julian Hunt of A.E. Housman 1 Letters from Laurence and Clemence Housman Julian Hunt 10 to Ida Stafford Northcote Rutupinaque litora and Lucan vi 67 Andrew Breeze 27 Orcadas and Juvenal ii 161 Andrew Breeze 36 And Thick on Severn Snow the Leaves Andrew Breeze 46 ‘Grasp the Nettle’: Some Thoughts on ASL XVI Darrell Sutton 59 Review of Edgar Vincent, A. E. Housman: Hero of the Hidden Life Andrew Maund 69 Biographies of Contributors 76 The Housman Society and Journal 77 Laurence Housman as Literary Executor of A.E. -

A Critical Study of the Seven Major Victorian Pessimistic Poets Frank W

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research Summer 1969 A critical study of the seven major Victorian pessimistic poets Frank W. Childrey Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Childrey, Frank W., "A critical study of the seven major Victorian pessimistic poets" (1969). Master's Theses. Paper 296. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE SEVEN MAJOR VICTORIAN PESSIMISTIC POETS A Thesis· Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Richmond In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Frank W. Childrey, Jr. August 1969 Approved for the Department of English and the Graduate School by: Direor of Thesis Chairman of the Department of English Dean o~~~ate ett;tL Table of Contents Chapter Page Introduction . 1 I Matthew Arnold . 1 II Edward FitzGerald . 29 III James Thomson 42 IV Algernon Charles Swinburne . 57 V Ernest Dowson . 83 VI Alfred Edward Housman . 95 VII Thomas Hardy . 112 Conclusion . ~ . 139 Bibliography . Vita . • . .· . i INTRODUCTION The following thesis is a critical study of seven sig nificant Victorian pessimistic poets. Having as its basis a seminar paper for Dr. Lewis F. Ball in which four of the Victorian pessimists were discussed, the original study was expanded in order to include the remaining three. -

Laurence Housman Papers, 1898-2007

Alfred Gillett Trust GB2075 LH, Laurence Housman Papers, 1898-2007 LH Laurence Housman Papers 1898-2007 ADMINISTRATIVE AND BIOGRAPHICAL HISTORY Laurence Housman (1865-1959), writer and artist, was the fourth son of the seven children of Edward Housman (1831-1894), solicitor of Perry Hall and the Clock House, Bromsgrove and his wife Sarah Jane Williams (1828-1871) of Woodchester, Gloucestershire. From 1924 Laurence resided in Street, Somerset, with his sister Clemence Housman (1861-1955), wood engraver and novelist. Classicist and poet A E Housman, best known for A Shropshire Lad, was their eldest brother (1859-1936). Laurence was educated at Bromsgrove School whereas Clemence was home educated and then attended the Bromsgrove School of Art. Following the sudden illness of their father, Laurence and Clemence moved to London in 1883 where they both attended Kennington Art School. Clemence trained here as a wood engraver and later worked for illustrated papers, supporting Laurence when he moved onto South Kensington Art School and was also pursuing interests in writing. Clemence was the first to publish, engraving her novel The Were-Wolf (1896) which was illustrated by Laurence. Laurence published his first work the following year and later turned to drama. Both siblings developed strong interests in women’s suffrage from 1908. Laurence became a high-profile activist, speaker and commentator, and Clemence co- founded and ran the Suffrage Atelier, made banners, raised funds for the Women’s Social and Political Union and was briefly imprisoned in 1911. Laurence and Clemence became friends of Roger Clark (1871-1961) and his wife Sarah Bancroft Clark (1877-1973), probably through their shared interests in the suffrage cause, with their friendship intensifying during World War One. -

Laurence Housman (1865-1959)

LAURENCE HOUSMAN (1865-1959) Born in 1865 in rural Worcestershire at his father’s ancestral home, Perry Hall, Bromsgrove, Laurence Housman was the sixth of seven children. The Housman children were a close-knit group of highly literary, artistic and intellectual siblings whose childhood play included writing sonnets and acting plays of their own composition. Housman’s respected eldest brother, Alfred, became the well-known poet and classical scholar, while his beloved sister, William Rothenstein. Drawing of Laurence Clemence, became a writer, wood-engraver, Housman. Lithograph, 1898. Liber and feminist. Laurence lived with Clemence Juniorum: Six Lithographed Drawings, London: 1899. Mark Samuels Lasner most of his life, working with her Collection, University of Delaware Library, Museums and Press. collaboratively on both artistic projects and suffrage campaigns. When he died in 1959, Housman had lived long enough after the Second World War to see the inchoate beginnings of the sexual revolution, second-wave feminism, and the gay-rights and peace movements that would dominate the 1960s. For the venerable Victorian suffragist, pacifist, socialist, homosexual, and advocate for sexual freedom and tolerance, this must have seemed like a glimpse into a new dawn. 1 Laurence Housman had a varied and prolific career over his long life, but one of its most significant aspects was his work as an artist/poet in the tradition of William Blake and the Pre-Raphaelites. His discovery of Gilchrist’s Life of Blake when he was seventeen was critically important to his career. Thereafter Blake was his model and inspiration; fittingly, Housman’s first publication was Selections from the Writings of William Blake (1893), for which he wrote an introductory essay. -

A. E. HOUSMAN a REASSESSMENT Also by Alan W

A. E. HOUSMAN A REASSESSMENT Also by Alan W. Holden MOLLY HOLDEN Selected Poems (zuith a Memoir of Molly Holde1z) Also by]. Roy Birch UNKIND TO UNICORNS Selected Comic Verse of A. E. Housman A. E. Houstnan A Reassessment Edited by Alan W. Holden and J. Roy Birch First published in Great Britain 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-333-65803-1 First published in the United States of America 2000 by ST. MARTIN'S PRESS, INC., Scholarly and Reference Division, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York. N.Y. 10010 ISBN 978-1-349-62281-8 ISBN 978-1-349-62279-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-62279-5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A E. Housman: a reassessment I edited by Alan W. Holden and J. Roy Birch. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Housman, A E. (Alfred Edward), 1859-1936-Criticism and interpretation. I. Holden, Alan W., 1926- ll. Birch, J. Roy. PR4809.H15A849 1999 821'.912-dc21 99-12180 CIP Selection, editorial matter and Introduction ©Alan W. Holden and J. Roy Birch 2000 Text© Macmillan Press Ltd 2000 Soft cover reprint of the hardcover I st edition 2000 978-0-312-22318-2 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written pennission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

The Housman Society Journal Vol.42 (Dec 2016)

Volume Forty-Two 2016 Editor: David Butterfield The Housman Society Founders John Pugh and Joe Hunt President Sir Christopher Ricks MA, BLitt., FBA Vice-Presidents Professor Archie Burnett MA, DPhil. Peter Clague MA, MBA Colin Dexter OBE, MA Professor Benjamin Franklin Fisher IV Paul Naiditch MA, MLS Jim Page MBE, MA Professor Norman Page MA, PhD, FRSCan. Sir Tom Stoppard OM, OBE Gerald Symons Chairman Vacancy Vice-Chairman Andrew Maund MA, MPhil. General Secretary Max Hunt MA, Dip. Ed. 7 Dowles Road, Bewdley, DY12 8HZ Treasurer Peter Sisley Ladywood Cottage, Baveney Wood, Cleobury Mortimer, DY14 8HZ Editor of the Journal David Butterfield MA, MPhil, PhD Queens’ College, Cambridge, CB3 9ET Editor of the Newsletter Julian Hunt FSA Committee Jane Allsopp BMus. Sonia French BA, Dip. Lib., Soc. Sci. Jennie McGregor-Smith Elizabeth Oakley MA, LRAM, Dip. RSA Pat Tansell Daniel Williams BA, PGCE Housman Society Journal Volume Forty-Two December 2016 The Housman Lecture Peter Parker 5 Laurence Housman and the Lord Chamberlain Elizabeth Oakley 25 A.E. Housman’s early biographers Martin Blocksidge 35 The Clock House Julian Hunt 62 Wake: The Silver Dusk Returning Andrew Breeze 71 William Housman in Brighton Julian Hunt 82 ‘Your affectionate but inefficient godfather’: the letters of A.E. Housman to G.C.A. Jackson David Butterfield 89 Biographies of Contributors 102 The Housman Society and Journal 104 The Housman Lecture: May 2016 The Name and Nature of Poetry Peter Parker This lecture takes its name from one given, very unwillingly, by A.E. Housman in Cambridge on 9 May 1933. It was as a poet rather than as a Classics scholar that Housman was invited to deliver the annual Leslie Stephen Lecture, which was named in honour of the critic and founder- editor of the Dictionary of National Biography. -

Fitzgerald's Rubáiyát

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The Australian National University FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát: A Victorian Invention Esmail Zare-Behtash A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University August 1994 Unless otherwise indicated, this thesis is based on original research conducted by the author as a research scholar in the Department of English at the Australian National University. (Signed) . ii Contents page Introduction 1 Chapter I: FitzGerald and His Invention 6 1.1. FitzGerald’s literary career and milieu 1.2. Omar’s life and time 1.3. Literature Review Chapter II: Persian Sources and Their Reception 83 2.1. Reception of Persian Literature in Britain 2.2. FitzGerald and Persian Literature Chapter III: FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát as a Victorian Product 131 3.1. FitzGerald’s Reinvented Poem 3.2. Victorian Poetry and FitzGerald’s Poem Chapter IV: Reception of the Rubáiyát by theVictorians 188 Bibliography 209 iii Acknowledgment I wish to express my heartfelt thanks to my supervisor Dr. Simon Haines who was always available and helpful and contributed greatly to the preparation of my thesis. I also wish to thank my adviser Professor A. H. Jones from Asian Studies of A. N. U. whose prompt and helpful comments were most valuable, especially with regard to sections on Omar’s life and time. Dr. David Parker, my adviser and former convener of the postgraduate program, provided constant encouragement and reassurance. I would like to thank Professor Stephen Prickett, a visiting-fellow at A. N. U., for several fruitful conversations in which he introduced me to the background of faith and doubt in the Victorian period.