Alexander Pope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sophocles, Ajax, Lines 1-171

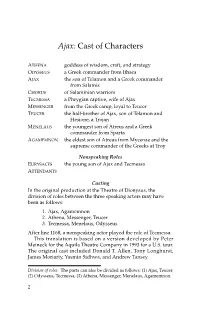

SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 2 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax: Cast of Characters ATHENA goddess of wisdom, craft, and strategy ODYSSEUS a Greek commander from Ithaca AJAX the son of Telamon and a Greek commander from Salamis CHORUS of Salaminian warriors TECMESSA a Phrygian captive, wife of Ajax MESSENGER from the Greek camp, loyal to Teucer TEUCER the half-brother of Ajax, son of Telamon and Hesione, a Trojan MENELAUS the youngest son of Atreus and a Greek commander from Sparta AGAMEMNON the eldest son of Atreus from Mycenae and the supreme commander of the Greeks at Troy Nonspeaking Roles EURYSACES the young son of Ajax and Tecmessa ATTENDANTS Casting In the original production at the Theatre of Dionysus, the division of roles between the three speaking actors may have been as follows: 1. Ajax, Agamemnon 2. Athena, Messenger, Teucer 3. Tecmessa, Menelaus, Odysseus After line 1168, a nonspeaking actor played the role of Tecmessa. This translation is based on a version developed by Peter Meineck for the Aquila Theatre Company in 1993 for a U.S. tour. The original cast included Donald T. Allen, Tony Longhurst, James Moriarty, Yasmin Sidhwa, and Andrew Tansey. Division of roles: The parts can also be divided as follows: (1) Ajax, Teucer; (2) Odysseus, Tecmessa; (3) Athena, Messenger, Menelaus, Agamemnon. 2 SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 3 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax SCENE: Night. The Greek camp at Troy. It is the ninth year of the Trojan War, after the death of Achilles. Odysseus is following tracks that lead him outside the tent of Ajax. -

HOMERIC-ILIAD.Pdf

Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power Contents Rhapsody 1 Rhapsody 2 Rhapsody 3 Rhapsody 4 Rhapsody 5 Rhapsody 6 Rhapsody 7 Rhapsody 8 Rhapsody 9 Rhapsody 10 Rhapsody 11 Rhapsody 12 Rhapsody 13 Rhapsody 14 Rhapsody 15 Rhapsody 16 Rhapsody 17 Rhapsody 18 Rhapsody 19 Rhapsody 20 Rhapsody 21 Rhapsody 22 Rhapsody 23 Rhapsody 24 Homeric Iliad Rhapsody 1 Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power [1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles. 8 So, which one of the gods was it who impelled the two to fight with each other in strife [eris]? 9 It was [Apollo] the son of Leto and of Zeus. For he [= Apollo], infuriated at the king [= Agamemnon], [10] caused an evil disease to arise throughout the mass of warriors, and the people were getting destroyed, because the son of Atreus had dishonored Khrysēs his priest. Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

1 (Disclaimers Moved to End of Document) the ILIAD of HOMER

(Disclaimers moved to end of document) THE ILIAD OF HOMER Rendered into English Prose for the use of those who cannot read the original by Samuel Butler BOOK I The quarrel between Agamemnon and Achilles--Achilles withdraws from the war, and sends his mother Thetis to ask Jove to help the Trojans--Scene between Jove and Juno on Olympus. Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. Many a brave soul did it send hurrying down to Hades, and many a hero did it yield a prey to dogs and vultures, for so were the counsels of Jove fulfilled from the day on which the son of Atreus, king of men, and great Achilles, first fell out with one another. And which of the gods was it that set them on to quarrel? It was the son of Jove and Leto; for he was angry with the king and sent a pestilence upon the host to plague the people, because the son of Atreus had dishonoured Chryses his priest. Now Chryses had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom: moreover he bore in his hand the 1 sceptre of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant's wreath, and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. "Sons of Atreus," he cried, "and all other Achaeans, may the gods who dwell in Olympus grant you to sack the city of Priam, and to reach your homes in safety; but free my daughter, and accept a ransom for her, in reverence to Apollo, son of Jove." On this the rest of the Achaeans with one voice were for respecting the priest and taking the ransom that he offered; but not so Agamemnon, who spoke fiercely to him and sent him roughly away. -

Provided by the Internet Classics Archive. See Bottom for Copyright

Provided by The Internet Classics Archive. See bottom for copyright. Available online at http://classics.mit.edu//Homer/iliad.html The Iliad By Homer Translated by Samuel Butler ---------------------------------------------------------------------- BOOK I Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. Many a brave soul did it send hurrying down to Hades, and many a hero did it yield a prey to dogs and vultures, for so were the counsels of Jove fulfilled from the day on which the son of Atreus, king of men, and great Achilles, first fell out with one another. And which of the gods was it that set them on to quarrel? It was the son of Jove and Leto; for he was angry with the king and sent a pestilence upon the host to plague the people, because the son of Atreus had dishonoured Chryses his priest. Now Chryses had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom: moreover he bore in his hand the sceptre of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant's wreath and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. "Sons of Atreus," he cried, "and all other Achaeans, may the gods who dwell in Olympus grant you to sack the city of Priam, and to reach your homes in safety; but free my daughter, and accept a ransom for her, in reverence to Apollo, son of Jove." On this the rest of the Achaeans with one voice were for respecting the priest and taking the ransom that he offered; but not so Agamemnon, who spoke fiercely to him and sent him roughly away. -

Sons and Fathers in the Catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233

Sons and fathers in the catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233 ANNETTE HARDER University of Groningen [email protected] 1. Generations of heroes The Argonautica of Apollonius Rhodius brings emphatically to the attention of its readers the distinction between the generation of the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War in the next genera- tion. Apollonius initially highlights this emphasis in the episode of the Argonauts’ departure, when the baby Achilles is watching them, at AR 1.557-5581 σὺν καί οἱ (sc. Chiron) παράκοιτις ἐπωλένιον φορέουσα | Πηλείδην Ἀχιλῆα, φίλωι δειδίσκετο πατρί (“and with him his wife, hold- ing Peleus’ son Achilles in her arms, showed him to his dear father”)2; he does so again in 4.866-879, which describes Thetis and Achilles as a baby. Accordingly, several scholars have focused on the ways in which 1 — On this marker of the generations see also Klooster 2014, 527. 2 — All translations of Apollonius are by Race 2008. EuGeStA - n°9 - 2019 2 ANNETTE HARDER Apollonius has avoided anachronisms by carefully distinguishing between the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War3. More specifically Jacqueline Klooster (2014, 521-530), in discussing the treatment of time in the Argonautica, distinguishes four periods of time to which Apollonius refers: first, the time before the Argo sailed, from the beginning of the cosmos (featured in the song of Orpheus in AR 1.496-511); second, the time of its sailing (i.e. the time of the epic’s setting); third, the past after the Argo sailed and fourth the present inhab- ited by the narrator (both hinted at by numerous allusions and aitia). -

Mediterranean Divine Vintage Turkey & Greece

BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Neapolis Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Abdera Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA JOINAllante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Elimia PydnaMEDITERRANEAN Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Dasaki Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos Torone Hephaistia Dorylaeum BOZCAADA Sigeion Kenchreai Omphatium Gonnus Skione Limnos MYSIA Uludag ESKİŞEHİR Eritium DIVINE VINTAGE Derecik Basilica Sidari Oxynia Myrina Kaz Mt. Passaron Soufli Troas Kebrene Skepsis UNESCO Meliboea Cassiope Gure bath BALIKESİR Dikilitaş Kanlıtaş Höyük Aiginion Neandra Karacahisar Castle Meteora Antandros Adramyttium Corfu UNESCO Larissa Lamponeia Dodoni Theopetra Gülpinar Pioniai Kulluoba Hamaxitos Seyitömer Höyük Keçi çayırı Syvota KÜTAHYA Grava Polimedion Assos Gerdekkaya Assos Mt.Pelion A E GTURKEY E A N S E A &Pyrrha GREECEMadra Mt. (Cotiaeum) Kumbet Lefkimi Theudoria Pherae Mithymna Midas City Ellina EPIRUS Passandra Perperene Lolkos/Gorytsa Antissa Bahses Mt. -

Alexander and the 'Defeat' of the Sogdianian Revolt

Alexander the Great and the “Defeat” of the Sogdianian Revolt* Salvatore Vacante “A victory is twice itself when the achiever brings home full numbers” (W. Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing, Act I, Scene I) (i) At the beginning of 329,1 the flight of the satrap Bessus towards the northeastern borders of the former Persian Empire gave Alexander the Great the timely opportunity for the invasion of Sogdiana.2 This ancient region was located between the Oxus (present Amu-Darya) and Iaxartes (Syr-Darya) Rivers, where we now find the modern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, bordering on the South with ancient Bactria (present Afghanistan). According to literary sources, the Macedonians rapidly occupied this large area with its “capital” Maracanda3 and also built, along the Iaxartes, the famous Alexandria Eschate, “the Farthermost.”4 However, during the same year, the Sogdianian nobles Spitamenes and Catanes5 were able to create a coalition of Sogdianians, Bactrians and Scythians, who created serious problems for Macedonian power in the region, forcing Alexander to return for the winter of 329/8 to the largest city of Bactria, Zariaspa-Bactra.6 The chiefs of the revolt were those who had *An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Conflict Archaeology Postgraduate Conference organized by the Centre for Battlefield Archaeology of the University of Glasgow on October 7th – 9th 2011. 1 Except where differently indicated, all the dates are BCE. 2 Arr. 3.28.10-29.6. 3 Arr. 3.30.6; Curt. 7.6.10: modern Samarkand. According to Curtius, the city was surrounded by long walls (70 stades, i.e. -

Brothers Fighting Together in the Iliad

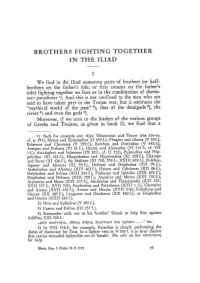

BROTHERS FIGHTING TOGETHER IN THE ILIAD I We find in the Iliad numerous pairs of brothers (or half brothers on the father's side, or first cousins on the father's side) fighting together on foot or in the combination of chario teer-paraibates 1). And this is not confined to the men who are said to have taken part in the Trojan war, but it embraces the "mythical world of the past" 2), that of the demigods 3), the rivers 4) and even the gods 5). Moreover, if we turn to the leaders of the various groups of Greeks and Trojans, as given in book 11, we find that a 1). Such for example are: Ajax Telarnonius and Teucer (the Atav'ts, cf. p. 291), Mynes and Epistrophus (II 692f.), Phegeus and Idaeus (V 10f.), Echemon and Chromios (V 159 f.), Krethon and Orsilochus (V 542 f,), Aesepus and Pedasus (VI 21 f.), Hector and Alexander (VI 514 f., cf. VII 1 f.), Ascalaphus and lalmenus (IX 82f., cf. II 512), Peisandrus and Hip polochus (XI 122 f.), Hippodamus and Hypeirochus (XI 328 f.), Charops and Socus (XI 426 f.), the Molione (XI 750, 709 f.; XXIII 638 f.), Polybus, Agenor and Akarnas (XI 59 f.), Helenos and Deiphobus (XII 94 f,), Archelochus and Akamas (XIV 463 f.), Hector and Cebriones (XII 86 f.), Deiphobus and Polites (XIII 533 f.), Podarces and Iphiclus (XIII 693 f,), Deiphohus and Helenos (XIII 780 f.), Ascanius and Morys (XIII 792 f.), Atymnius and Maris (XVI 317 f.), Antilochus and Thrasymedes (XVI 322; XVII 377 f.; XVII 705), Euphorbus and Polydamas (XVII 1 f.), Chromius and Aretus (XVII 492 f.), Aretus and Hector (XVII 516), Polydorus and Hector (XX 407 f,), Laogonus and Dardanus (XX 460 f.), or Deiphobus and Hector (XXII 226 f.). -

The Successors: Alexander's Legacy

The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy November 20-22, 2015 Committee Background Guide The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy 1 Table of Contents Committee Director Welcome Letter ...........................................................................................2 Summons to the Babylon Council ................................................................................................3 The History of Macedon and Alexander ......................................................................................4 The Rise of Macedon and the Reign of Philip II ..........................................................................4 The Persian Empire ......................................................................................................................5 The Wars of Alexander ................................................................................................................5 Alexander’s Plans and Death .......................................................................................................7 Key Topics ......................................................................................................................................8 Succession of the Throne .............................................................................................................8 Partition of the Satrapies ............................................................................................................10 Continuity and Governance ........................................................................................................11 -

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 IX – BOEOTIA – A COLONY OF THE MINI AND THE FLEGI .....71 X – COLONIZATION -

Classical Reception in Contemporary Women's

CLASSICAL RECEPTION IN CONTEMPORARY WOMEN’S WRITING: EMERGING STRATEGIES FROM RESISTANCE TO INDETERMINACY by POLLY STOKER A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Classics, Ancient History, and Archaeology School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham April 2019 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The reader who rewrites remains a vital interlocutor between the classical past and the modern classicist. However, the neglect of the female reader in classical reception studies is an omission that becomes ever more conspicuous, and surely less sustainable, as women writers continue to dominate the contemporary creative field. This thesis makes the first steps towards fashioning a new aesthetic model for the female reader based on irony, ambivalence, and indeterminacy. I consider works by Virginia Woolf, Alice Oswald, Elizabeth Cook, and Yael Farber, all of whom largely abandon ‘resistance’ as a strategy of rereading and demand a new theoretical framework that can engage with and recognize the multivalence of women’s reading and rewriting.