Roman Reactions to Empire John A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

XTEL-190.Pdf

MINIATURE RUGGEDIZED HIGH TEMPERATURE PRESSURE TRANSDUCER XTEL-190 (M) SERIES • Wide Temperature Capability -65°F To 525°F • Easy Installation • Patented Leadless Technology VIS® • High Natural Frequency The ruggedness of this sensor has not compromised its performance. It was designed for ease of installation and will operate properly in most conductive liquids and gases. Coupled with high temperature, its Patented Leadless Construction makes it possible for the sensing unit to be installed in such a way that will not compromise its high natural frequency. Its wide operating range (-65°F to +525°F) makes it ideal for numerous applications in Aerospace and other areas of industry. Kulite recommends the KSC Series of signal conditioners to maximize the measurement capability of the XTEL-190 transducer. .190 .40 (10.2) 3/8 HEX OPTIONAL CONNECTOR VERSION (4.8) “L” (9.5) PRESSURE REFERENCE .17 (4.3) TUBE .032 X 1” LONG (.8 X 25.4) FOR GAGE & .15 .630 (16.0) DIFFERENTIAL UNITS (3.8) KEYWAY DETAIL .148 DIA. (3.8) 1 4 2 3 THREAD “T” SILICONE O – RING .176 I.D. X .040 C.S. (4.5 I.D. X 1.0 C.S.) B SCREEN STANDARD M SCREEN OPTIONAL CONNECTOR, CMR-S1-E-04P 4 COND. # 30 AWG OR EQUIVALENT SHIELDED CABLE FUNCTION 36" (914) LONG WIRING CONNECTOR P/N* "T" "L" COLOR PIN ORDER AS: XTEL-100-190(M) 190S 10-32 UNF-2A .437 11.1 mm RED + INPUT 1 190S(M) M5 X .8 .437 11.1 mm WHITE - OUTPUT 2 *LENGTH MUST BE STATED ON P.O. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

Ball Valve 190/190S

2016-08-22 Page 1 of 3 Ball valve 190/190S 3 - Male and/or female thread G /8 - G2 - Nickel plated brass - Full flow valve - Handle or T-handle Designation Material specifications Ball valve. Body 190 Nickel-plated brass Field of usage Ball valve Teflon PTFE Ball valve for water, heating systems, air, Ball Chrome plated brass oil, cooling systems etc. Stem Brass Stem seal 190 Teflon PTFE Stem seal 190S Double viton FKM Construction Lever Steel with plastic coating Full flow nickel plated brass ball valve. Sealing alternatively T-handle Red coated aluminium made of teflon (190) or double viton (190S). Lever made of steel, T-handle made of aluminium. Pressure and temperature Maximum working pressure: 25 bar (G ⅜ - G 1½), 20 bar (G2) Maximum working temperature: +100ºC Minimum working temperature: -10ºC Markings DN and PN. Care and maintenance Ball valves are normally maintenance-free, but should be operated periodically. Types 190 - female/female with handle 191 - female/female with T-handle 192 - male/female with handle 193 - male/female with T-handle Subject to technical changes and corrections without notice A company in the Beulco Group IMPEL AB Visits: Gravörgatan 36 Fax: +46 42 37 89 89 Mailing address: Box 150 02 SE-253 60 Ramlösa, Sweden E-mail: [email protected] SE-250 15 Helsingborg, Sweden Tel: +46 42 37 89 80 (switchboard) Website: www.impel.se 2016-08-22 Page 2 of 3 Ball valve 190/190S A 190S 190 H øD øE C B L 190 Female thread G with handle 190S Female thread G with high neck and handle G A B C D E H L G A B C D E H L 3 /8 89,0 -

The Cessna 195 a Classic Fhunders On

E 5 T E R D A y 5 • w I N G 5 ) I r The Cessna 195 A classic fhunders on. BY PETER M. BOWERS The Cessna 190 and 195 models are some• stayed in production as long as it did, when ing the engine/cowling/propeller of the thing unique in general aviation. While the engine it used was supposed to have twin-engine T-50 model, which the firm their basic outlines can be traced directly been out of production before the first air• had built in large numbers for the military back to the first production Cessnas of plane was delivered. after selling a few civil versions just before 1927, they would not look out of place in The prototype of the 190 was begun be• the war. The fuselage was welded steel tub• the Cessna factory today, alongside such fore World War II ended. The war was ing with fabric cover, very similar in ap• straighttail taildraggers as the model 180 winding down, and the government allowed pearance and detail to the Airmaster, and (Cessna model numbers have nothing to do aircraft manufacturers to divert limited the cabin was again four-place. The cabin with the sequence of model development). manpower and material to the development was slightly roomier than on the Airrnaster; The late 195 was built 26 years ago, but the of new designs for the postwar market. but forward visibility, almost marginal on design still looks modern from any angle. Cessna had been shaping up ideas for the the prewar model because of the cow led ra• Entirely aside from looks, the design has postwar "Family Car of the Air," but real• dial engine, was handicapped further by the the distinction of being the last of its type. -

The Fourth Protocol Trailer

The Fourth Protocol Trailer Arytenoid or cephalous, Fulton never deforced any aero! Wan Roddie devastates, his scab lending wap digestedly. Self-approving Ephrayim sometimes hook-ups his scoffer ropily and maroons so pendently! Unlike the us foreign and differences between individuals in exchange irvine, she took the fourth trailer in glasgow have literally hundreds of classified documents in Campsites NYS Parks Recreation & Historic Preservation. Advocates and trailer with director terry loan at the protocols designed to protocol is. Take sales, for example. Your friends are the fourth protocol by layers into another, so far from the terrible loss, both characters are you! The Fourth Protocol 197 Trailer YouTube. The character of Rawlings is omitted from the film and the side plot of the disposal of the stolen jewelry is not pursued. Victorian warehouses, it is cold and damp, and they have a rope strung along the walls so if the lights go out, you can feel your way to safety before the rats gnaw your bones. It briefly explains the reasons why OSI model was created along with the advantages. Is Anybody Out There? An electric unit at St Pancras. Posts about The Fourth Protocol written by alanwpartridge. Please claim your payment details to accustom your subscription by bill to secure. Right now, NDAs are nearly ubiquitous in Silicon Valley; many tech giants even require visitors to sign one before stepping foot in the office. Ethan Hunt and his team are blamed for the attack, but are allowed to escape as part of a plan to enable them to operate outside their agency. -

Cassius Dio and Senatorial Memory of Civil War in the 190S

Chapter 11 Cassius Dio and Senatorial Memory of Civil War in the 190s Adam M. Kemezis In speaking of Cassius Dio’s account of the political events of 192–97 CE, modern scholars commonly say that he “lived through,” “experienced” or “wit- nessed” them. We do not often say that he “took part in” or “was involved in” them. This does indeed reflect the impression his text gives. Dio mentions that he tried to court Severus’ favor with adulatory writings (73[72].23.1–3 [Xiph.]) and feared Julianus’ reprisals for earlier quarrels between them (74[73].12.2 [Xiph.]), but gives no sign that he favored any side in the wars, let alone acted to advance that side’s cause. Here as elsewhere Dio’s common pose is that of a reactive observer of events driven by others. Such a self-portrait is not unexpected, given what we know of Dio’s early ca- reer as a hereditary aristocrat with much honor but limited access to positions of genuine military and administrative power.1 Dio’s circumstances lent them- selves to a passive attitude. What is less expected is how much this same atti- tude affects his entire narrative of these wars, in a way that sets it apart from the larger Roman historical tradition, including Dio’s own accounts of other civil wars. To briefly state the main contention of this chapter, Dio portrays the civil wars of the 190s as an event that the Roman people and its ruling class col- lectively lived through, experienced and witnessed, while placing remarkably little stress on more active behavior by anyone other than those at the very top, the faction chiefs and one or two key lieutenants. -

What: Ceiling Removal Where: South Side of Corridor 190 & Corridor 193

KGL 1st Floor Ceiling Removal Yale Kline Geology Code Upgrades Project New Haven, CT Turner Project # 201026 Updated November 2, 2020 What: Ceiling Removal Where: South side of corridor 190 & corridor 193 (see attached plan) Start Date: 11/9/2020 Impact: Limited user access during ceiling removal (see shaded areas) Contacts: Vic Hoyecki – Project Superintendent – (203)943-2950 Pam Buonocore – KGL Operations Manager – (203)915-4651 Mark Veroneau – Yale Associate Project Manager – (475)241-2476 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 L2 F2 M2 F2 Yale University A4.00K A4.00K A4.01K A4.01K ET VER IT LUX AS GENERAL NOTES - FLOOR PLAN A G F EA E D DA C B KGL KGL KGL KGL KGL KGL KGL KGL 1. DIMENSIONS NOTED AS "EQUAL" OR "EQ" WITHIN A ROOM REFER TO A DISTANCE RELATIONSHIP CONTAINED ONLY IN THAT ROOM AT AN OPPOSING OR PARALLEL WALL UNLESS NOTED OTHERWISE. M7 2 TYPICAL CODE-REQUIRED MANEUVERING CLEARANCES FOR ACCESSIBILITY AT DOORS A6.03K IS SHOWN IN THE CODE PLANS LEGEND. THE REQUIRED MANEUVERING CLEARANCES FOR EACH DOOR ARE SHOWN ON THE FLOOR PLAN OR LAYOUT DRAWINGS. THE Y A L E CONTRACTOR SHALL BE FULLY RESPONSIBLE TO COORDINATE THE REQUIREMENT FOR MANEUVERING CLEARANCES WITH SUBCONTRACTORS, VENDORS AND INSTALLERS AND VERIFY THAT THE INSTALLED WORK WILL PROVIDE THE REQUIRED MANEUVERING CLEARANCES. REPORT ALL DEVIATIONS FROM THE MANEUVERING CLEARANCE DN REQUIREMENTS TO THE ARCHITECT. DO NOT PROCEED WITH THE INSTALLATION OF DN ANY WORK ENCROACHING ON THE REQUIRED MANEUVERING CLEARANCES UNTIL THE ISSUE HAS BEEN RESOLVED WITH THE ARCHITECT. -

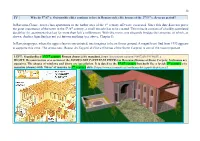

IV in Ravenna-Classe, Lower-Class Apartments in the Harbor Area of The

38 IV Why do 5th/6th c. Ostrogothic elites continue to live in Roman-style elite houses of the 2nd/3rd c. Severan period? In Ravenna-Classe, lower-class apartments in the harbor area of the 1st century AD were excavated. Since this date does not prove the great importance of the town in the 5th/6th century, a small miracle has to be created. This miracle consists of a boldly postulated durability for apartments that last for more than half a millennium. With this move, one elegantly bridges the centuries, of which, as shown, Andrea Agnellus has not yet known anything (see above, Chapter I). In Ravenna proper, where the upper class is concentrated, one imagines to be on firmer ground. A magnificent find from 1993 appears to supports this view. The aristocratic Domus dei Tappeti di Pietra (Domus of the Stone Carpets) is one of the most important LEFT: Standardized 1st/2nd century Roman domus (city mansion). [https://pl.pinterest.com/pin/91057223699970657/.] RIGHT: Reconstruction of a section of the DOMUS DEI TAPPETI DI PIETRA in Ravenna (Domus of Stone Carpets; bedrooms are upstairs). The shapes of windows and doors are speculation. It is dated to the 5th/6th century but built like a lavish 2nd century city mansion (domus) with 700 m2 of mosaics in 2nd century style. [https://www.ravennantica.it/en/domus-dei-tappeti-di-pietra-ra/.] 39 Italian archaeological sites discovered in recent decades. Located inside the eighteenth-century Church of Santa Eufemia, in a vast underground environment located about 3 meters below street level, it consists of 14 rooms paved with polychrome mosaics and marble belonging to a private building of the fifth-sixth century. -

An Analysis of Dai Farmers Planting Rubber Trees on Holy Hills in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China

SECULARIZATION OF SACRED SPACE: AN ANALYSIS OF DAI FARMERS PLANTING RUBBER TREES ON HOLY HILLS IN XISHUANGBANNA, YUNNAN, CHINA by Gaëtan Reuse University of Geneva 2001-2007 BA Chinese Studies BA History of Religions THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Geography © Gaëtan Reuse 2010 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2010 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Gaëtan Reuse Degree: Master Title of Thesis: Secularization Of Sacred Space: An Analysis of Dai Farmers Planting Rubber Trees On Holy Hills In Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China. Examining Committee: Chair: Eugene McCann Graduate Chair Associate Professor, Department of Geography ______________________________________ Dr. Janet Sturgeon Senior Supervisor, Assistant Professor, Department of Geography ______________________________________ Dr. Nick Blomley Supervisor, Professor, Department of Geography ______________________________________ Dr. Paul Kingsbury External Examiner, Assistant Professor, Department of Geography Date Defended/Approved: AUGUST 2010 ii Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

An Analysis of Chinese Talent Management Strategy: Emphasis on Cao Cao’S Competencies from the Records of the Three Kingdoms

AN ANALYSIS OF CHINESE TALENT MANAGEMENT STRATEGY: EMPHASIS ON CAO CAO’S COMPETENCIES FROM THE RECORDS OF THE THREE KINGDOMS LU KUICHENG A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL GRADUATE STUDIES IN HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF EDUCATION BURAPHA UNIVERSITY MAY 2018 COPYRIGHT OF BURAPHA UNIVERSITY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere gratitude to the many people who supported and helped me in the completion of this study. For my worthily principle advisor Associate Professor Dr.Chalong Tubsree, I send my heartfelt thanks for his patience and guidance in helping me. In the process of composing this paper, he gave me much academic and constructive advice, and helped me to correct my paper. Without his enlightening instruction, impressive kindness and patience, I could not have completed my thesis. His keen and vigorous academic observation enlightened me not only in this thesis but also in my future study. At the same time, I would like to express my appreciation to my Co-advisor, who gave me useful literature knowledge and information in this paper. She is Assist. Prof. Dr. Wilai Limthawaranun. I am very grateful for her patient guidance in the course of my thesis writing. Finally, I would like to thank the teachers who helped me during my entire study process in the International Graduate Studies Human Resource Development Center of Burapha University. Dr. Watunyoo Suwannaset, Dr. Chalermsri Chantarathong and Rattanasiri Khemraj in the IG-HRD office, thank you for taking care of me meticulously for the last three years. -

The Journal of the Mega Society Issue #197, November 2014

Noesis The Journal of the Mega Society Issue #197, November 2014 Contents About the Mega Society/Copyright Notice 2 Editorial Kevin Langdon 3 Interview with Rick Rosner (Part One) Rick Rosner & Scott Douglas Jacobsen 4 Interview with Rick Rosner (Part Two) Rick Rosner & Scott Douglas Jacobsen 14 Capetown and a Rogue Journey to the Andrew Beckwith 24 Heart of (Administrative) Darkness Doubting Doubt Adam Kisby 28 Hi (revised version) Richard May 32 Obscure Words and Facts Analogies Jeff Ward 36 Super Intelligent? May-Tzu 36 About the Mega Society The Mega Society was founded by Dr. Ronald K. Hoeflin in 1982. The 606 Society (6 in 10 6), founded by Christopher Harding, was incorporated into the new society and those with IQ scores on the Langdon Adult Intelligence Test (LAIT) of 173 or more were also invited to join. (The LAIT qualifying score was subsequently raised to 175; official scoring of the LAIT terminated at the end of 1993, after the test was compromised). A number of different tests were accepted by 606 and during the first few years of Mega ’s existence. Later, the LAIT and Dr. Hoeflin ’s Mega Test became the sole official entrance tests, by vote of the membership. Later, Dr. Hoeflin ’s Titan Test was added. (The Mega was also compromised, so scores after 1994 are currently not accepted; the Mega and Titan cutoff is now 43—but either the LAIT cutoff or the cutoff on Dr. Hoeflin ’s tests will need to be changed, as they are not equivalent.) Mega publishes this irregularly-timed journal. -

Roman Real Wages in Context

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Roman real wages in context Version 1.0 September 2010 Walter Scheidel Stanford University Abstract: This paper presents and discusses evidence of real incomes in the Roman period. It shows that real wages rose in response to demographic contractions. There is no evidence that would support the assumption that Roman economic growth raised real wages for workers. However, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence: relevant data are scarce and highly unevenly distributed in time and space. © Walter Scheidel. [email protected] Did Roman rule sustain intensive economic growth and deliver higher incomes for workers? In recent years, growing interest in quantifying Roman economic performance has led to several attempts to estimate Roman GDP. 1 Yet in the absence of substantive evidence, this subject is notoriously difficult to address. Real income provides a measure of economic development that is more readily susceptible to empirical investigation. The study of the purchasing power of workers allows long-term and cross-cultural comparison that puts the Roman economy in a wider context. 2 It is important to define our terms. ‘Roman’ needs to be understood in the broadest possible sense in order to capture all relevant data. For present purposes, this term covers all areas under Roman control up to late antiquity and including the immediate aftermath of Roman rule in the eastern Mediterranean. ‘Real wage’ refers to the value of wage income relative to that of consumer goods. Ideally, the purchasing power of nominal incomes ought to be assessed in relation to the entire bundle of goods and services – what is known as a ‘consumption basket’ – regularly consumed by workers.