The Ontological Status of Sin in the Theology of Hans Urs Von Balthasar Craig W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antiphonary of Bangor and Its Musical Implications

The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications by Helen Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Helen Patterson 2013 The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications Helen Patterson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hymns of the Antiphonary of Bangor (AB) (Antiphonarium Benchorense, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana C. 5 inf.) and considers its musical implications in medieval Ireland. Neither an antiphonary in the true sense, with chants and verses for the Office, nor a book with the complete texts for the liturgy, the AB is a unique Irish manuscript. Dated from the late seventh-century, the AB is a collection of Latin hymns, prayers and texts attributed to the monastic community of Bangor in Northern Ireland. Given the scarcity of information pertaining to music in early Ireland, the AB is invaluable for its literary insights. Studied by liturgical, medieval, and Celtic scholars, and acknowledged as one of the few surviving sources of the Irish church, the manuscript reflects the influence of the wider Christian world. The hymns in particular show that this form of poetical expression was significant in early Christian Ireland and have made a contribution to the corpus of Latin literature. Prompted by an earlier hypothesis that the AB was a type of choirbook, the chapters move from these texts to consider the monastery of Bangor and the cultural context from which the manuscript emerges. As the Irish peregrini are known to have had an impact on the continent, and the AB was recovered in ii Bobbio, Italy, it is important to recognize the hymns not only in terms of monastic development, but what they reveal about music. -

The Centrality of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass at Christendom College

THE CENTRALITY OF THE HOLY SACRIFICE OF THE MASS AT CHRISTENDOM COLLEGE The Church teaches that the Eucharist is “the source and summit of the Christian life”1 and that the celebration of the Mass “is a sacred action surpassing all others. No other action of the Church can equal its efficacy.”2 That is why “as a natural expression of the Catholic identity of the University. members of this community . will be encouraged to participate in the celebration of the sacraments, especially the Eucharist, as the most perfect act of community worship.”3 Those central truths are taught and lived at Christendom College, a “Catholic coeducational college institutionally committed to the Magisterium”4 of the Church, in the following ways: The Celebration of the Sacred Liturgy The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass • Mass is offered frequently: twice daily Monday through Thursday, three times on MONDAY (Friday), twice on Saturday, and once on Sunday (the day on which we gather as one family). • Mass in the Roman Rite is celebrated in all the ways offered by the Church: in the Ordinary Form in both English and Latin, and in the Extraordinary Form from one to three times per week, as circumstances permit. • The Ordinary Form of the Mass is celebrated with the solemnity appropriate to each feast, utilizing worthy sacred vessels and vestments, and drawing upon the Church’s rich tradition of chant, polyphony, and hymnody. • The Ordinary Form of the Mass is celebrated reverently and with rubrical fidelity. • No classes or other activities are scheduled during Mass times. • The majority of the College community attends daily Mass regularly and with great devotion. -

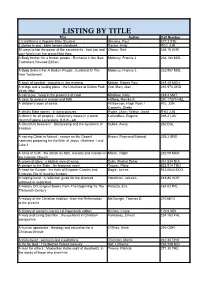

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

Newsletter 2020 I

NEWSLETTER EMBASSY OF MALAYSIA TO THE HOLY SEE JAN - JUN 2020 | 1ST ISSUE 2020 INSIDE THIS ISSUE • Message from His Excellency Westmoreland Palon • Traditional Exchange of New Year Greetings between the Holy Father and the Diplomatic Corp • Malaysia's contribution towards Albania's recovery efforts following the devastating earthquake in November 2019 • Meeting with Archbishop Ian Ernest, the Archbishop of Canterbury's new Personal Representative to the Holy See & Director of the Anglican Centre in Rome • Visit by Secretary General of the Ministry of Water, Land and Natural Resources • A Very Warm Welcome to Father George Harrison • Responding to COVID-19 • Pope Called for Joint Prayer to End the Coronavirus • Malaysia’s Diplomatic Equipment Stockpile (MDES) • Repatriation of Malaysian Citizens and their dependents from the Holy See and Italy to Malaysia • A Fond Farewell to Mr Mohd Shaifuddin bin Daud and family • Selamat Hari Raya Aidilfitri & Selamat Hari Gawai • Post-Lockdown Gathering with Malaysians at the Holy See Malawakil Holy See 1 Message From His Excellency St. Peter’s Square, once deserted, is slowly coming back to life now that Italy is Westmoreland Palon welcoming visitors from neighbouring countries. t gives me great pleasure to present you the latest edition of the Embassy’s Nonetheless, we still need to be cautious. If Inewsletter for the first half of 2020. It has we all continue to do our part to help flatten certainly been a very challenging year so far the curve and stop the spread of the virus, for everyone. The coronavirus pandemic has we can look forward to a safer and brighter put a halt to many activities with second half of the year. -

ABSTRACT Love Itself Is Understanding: Balthasar, Truth, and the Saints Matthew A. Moser, Ph.D. Mentor: Peter M. Candler, Jr., P

ABSTRACT Love Itself is Understanding: Balthasar, Truth, and the Saints Matthew A. Moser, Ph.D. Mentor: Peter M. Candler, Jr., Ph.D. This study examines the thought of Hans Urs von Balthasar on the post-Scholastic separation between dogmatic theology and the spirituality of Church, which he describes as the loss of the saints. Balthasar conceives of this separation as a shattering of truth — the “living exposition of theory in practice and of knowledge carried into action.” The consequence of this shattering is the impoverishment of both divine and creaturely truth. This dissertation identifies Balthasar’s attempt to overcome this divorce between theology and spirituality as a driving theme of his Theo-Logic by arguing that the “truth of Being” — divine and creaturely — is most fundamentally the love revealed by Jesus Christ, and is therefore best known by the saints. Balthasar’s attempted re-integration of speculative theology and spirituality through his theology of the saints serves as his critical response to the metaphysics of German Idealism that elevated thought over love, and, by so doing, lost the transcendental properties of Being: beauty, goodness, and truth. Balthasar constructively responds to this problem by re-appropriating the ancient and medieval spiritual tradition of the saints, as interpreted through his own theological master, Ignatius of Loyola, to develop a trinitarian and Christological ontology and a corresponding pneumatological epistemology, as expressed through the lives, and especially the prayers, of the saints. This project will follow the structure and rhythm of Balthasar’s Theo-Logic in elaborating the initiatory movement of his account of truth: phenomenological, Christological, and pneumatological. -

Fr Cantalamessa Gives First Advent Reflection to Pope and Roman Curia

Fr Cantalamessa gives first Advent reflection to Pope and Roman Curia The Preacher of the Papal Household, Fr Raniero Cantalamessa, gives his first Advent reflection at the Redemptoris Mater Chapel in the Apostolic Palace. Below is the full text of his sermon. P. Raniero Cantalamessa ofmcap BLESSED IS SHE WHO BELIEVED!” Mary in the Annunciation First Advent Sermon 2019 Every year the liturgy leads us to Christmas with three guides: Isaiah, John the Baptist and Mary, the prophet, the precursor, the mother. The first announced the Messiah from afar, the second showed him present in the world, the third bore him in her womb. This Advent I have thought to entrust ourselves entirely to the Mother of Jesus. No one, better than she can prepare us to celebrate the birth of our Redeemer. She didn’t celebrate Advent, she lived it in her flesh. Like every mother bearing a child she knows what it means be waiting for somebody and can help us in approaching Christmas with an expectant faith. We shall contemplate the Mother of God in the three moments in which Scripture presents her at the center of the events: the Annunciation, the Visitation and Christmas. 1. “Behold, / am the handmaid of the Lord” We start with the Annunciation. When Mary went to visit Elizabeth she welcomed Mary with great joy and praised her for her faith saying, “Blessed is she who believed there would be a fulfillment of what was spoken her from the Lord” (Lk 1:45). The wonderful thing that took place in Nazareth after the angel’s greeting was that Mary “believed,” and thus she became the “mother of the Lord.” There is no doubt that the word “believed” refers to Mary’s answer to the angel: “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word (Lk 1:38). -

Beauty As a Transcendental in the Thought of Joseph Ratzinger

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2015 Beauty as a transcendental in the thought of Joseph Ratzinger John Jang University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Jang, J. (2015). Beauty as a transcendental in the thought of Joseph Ratzinger (Master of Philosophy (School of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/112 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School of Philosophy and Theology Sydney Beauty as a Transcendental in the Thought of Joseph Ratzinger Submitted by John Jang A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy Supervised by Dr. Renée Köhler-Ryan July 2015 © John Jang 2015 Table of Contents Abstract v Declaration of Authorship vi Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 Structure 3 Method 5 PART I - Metaphysical Beauty 7 1.1.1 The Integration of Philosophy and Theology 8 1.1.2 Ratzinger’s Response 11 1.2.1 Transcendental Participation 14 1.2.2 Transcendental Convertibility 18 1.2.3 Analogy of Being 25 PART II - Reason and Experience 28 2. -

Hans Urs Von Balthasar - Ein Grosser Churer Diözesan SCHRIFTENREIHE DER THEOLOGISCHEN HOCHSCHULE CHUR

Peter HENR1c1 (Hrsg.) Hans Urs von Balthasar - ein grosser Churer Diözesan SCHRIFTENREIHE DER THEOLOGISCHEN HOCHSCHULE CHUR Im Auftragder Theologischen Hochschule Chur herausgegeben von Michael DURST und Michael FIEGER Band7 Peter HENRICI (Hrsg.) Hans Urs von Balthasar - ein grosser Churer Diözesan Mit Beiträgen von Urban FINK Alois M. HAAS Peter HENRICI KurtKocH ManfredLOCHBRUNNER sowie einer Botschaft von Papst BENEDIKT XVI. AcademicPress Fribourg BibliografischeInformation Der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografischeDaten sind im Internetüber http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Die Druckvorlagen der Textseiten wurden vom Herausgeber der Reihe als PDF-Datei zur Verfügunggestellt. © 2006 by Academic Press Fribourg / Paulusverlag Freiburg Schweiz Herstellung: Paulusdruckerei Freiburg Schweiz ISBN-13: 978-3-7278-1542-3 ISBN-10: 3-7278-1542-6 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort . 7 Abkürzungsverzeichnis . 9 Bischof Kurt KOCH Von der Schönheit Gottes Zeugnis geben . 11 Alois M. HAAS Evangelisierung der Kultur . 19 Weihbischof Peter HENRICI Das Gleiche auf zwei Wegen: Karl Rahner und Hans Urs von Balthasar . 39 Manfred LOCHBRUNNER Hans Urs von Balthasar und seine Verbindung mit dem Bistum Chur . 55 Urban FINK „Ihr stets im Herrn ergebener Hans Balthasar“. Hans Urs von Balthasar und der Basler Bischof Franziskus von Streng . 93 Botschaft von Papst BENEDIKT XVI. an die Teilnehmer der Internationalen Tagung in Rom (Lateran-Universität) anlässlich des 100. Geburtstages des Schweizer Theologen Hans Urs von Balthasar . 131 Die Autoren . 135 5 Vorwort Hans Urs VON BALTHASAR ist wohl der weltweit bekannteste katholische Theologe der Deutschschweiz im 20. Jahrhundert. Dass der gebürtige Luzerner und „Basler Theologe“ Churer Diözesanpriester war, ist weit weniger bekannt. Sein 100. -

1 the SUN BEHIND the SUN Frank Shirbroun, St. Augustine's In

1 THE SUN BEHIND THE SUN Frank Shirbroun, St. Augustine’s in-the-Woods, April 30, 2017 INTRODUCTION: Teresa and I are highly honored to have a part in the series of Celtic Christian Eucharists that begins today. Last fall, at the invitation of Father Eric Stelle, we did a similar series at St. John’s, Gig Harbor. Many there found the series especially nourishing to their own spiritual pilgrimages and we did, too. So, when St. Augustine’s Adult Formation Committee asked us to do something similar here, we were happy to say, “Yes!” What Teresa and I will do each Sunday in this series is to lift up several Celtic Christians who are identified with the distinctive themes of Celtic Christian spirituality. Our hope is this: if we learn something about these Celtic Christians and their faith, we may gain enlightenment and encouragement for our own Christian pilgrimage. I don’t know how much you know about “Celtic Christian Spirituality”, so, perhaps I should begin by saying something about the meaning of this term as we shall use it during this series. We are talking about a unique way of being Christian found in lands around the Irish Sea, especially Scotland, Northern Britain, Wales, Cornwall, and Ireland. It is a very early form of Christianity that flourished there mainly from the fifth to the ninth centuries A.D., up to the Viking raids in the 800s, which sacked and destroyed many Celtic Christian communities. Now, I am being careful to use the term “Celtic Christian Spirituality” because we are not talking about a Celtic church in the sense of an institution with a central organization, or a hierarchy, or a uniform set of practices like our Episcopal church. -

How Do the Writings of Pope Benedict XVI on "Transformation" Apply to a Couple's Growth in Holiness in Sacramental Marriage?

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 How do the writings of Pope Benedict XVI on "transformation" apply to a couple's growth in holiness in sacramental marriage? Houda Jilwan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Jilwan, H. (2018). How do the writings of Pope Benedict XVI on "transformation" apply to a couple's growth in holiness in sacramental marriage? (Master of Philosophy (School of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/194 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW DO THE WRITINGS OF POPE BENEDICT XVI ON “TRANSFORMATION” APPLY TO A COUPLE’S GROWTH IN HOLINESS IN SACRAMENTAL MARRIAGE? Houda Jilwan A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy School of Philosophy and Theology The University of Notre Dame Australia 2018 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1: The universal call to holiness .................................................................................. 11 1.1 Meaning of holiness ..................................................................................................... 11 1.2 A quick overview of the universal call to holiness in Scripture and Tradition .................. -

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8. -

1 Introduction David Moss, Edward T

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89147-9 - The Cambridge Companion to Hans Urs von Balthasar Edited by Edward T. Oakes and David Moss Excerpt More information 1 Introduction david moss, edward t. oakes At least among professional theologians, Hans Urs von Balthasar tends to perplex more than he manages to inspire. To be sure, he can inspire. For example, the journal he founded, Communio, now appears in twelve languages (including Arabic). But subscribers never exceed the number – itself already quite small – usual for most other professional theological journals. More to the point, few Catholic departments of theology in Europe or North America consider it essential to have a Balthasarian expert on their respective faculties (a similar attitude towards liberation theology, transcendental Thomism, or feminist theology, by comparison, would seem vaguely revanchist). To some extent, however, this situation has begun to change. In fact, this volume in the Cambridge Companion series testifies to what seems to be an incipient sea change in attitudes towards this unusually productive, subtle, and complex theologian.1 For that reason, the editors wish to stress that this collection of essays by a wide array of scholars wishes not so much to inspire as to address the perplexity that seems to be an inherent part of everyone’s reaction to Balthasar’s thought. We make no claim to have resolved the perplexity that so many readers feel upon encountering his theology for the first (or even umpteenth) time. Perhaps, after all, perplexity is but the reader’s inevitable response to an author’s complexity. Thus, all that the following chapters can realistically hope to accomplish is to address that perplexity through a careful exposition and critique of his complex thought.