Synthesizing Dance and Conducting Pedagogy for Heightened Creativity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The B-Boy Summit Internationally Acclaimed B-Boy/B-Girl Event

THE B-BOY SUMMIT INTERNATIONALLY ACCLAIMED B-BOY/B-GIRL EVENT Produced by No Easy Props OVERVIEW The B-boy Summit continues to be a major trendsetter in Hip-Hop street dance, art and music culture. Established in 1994, The Summit presented innovative ideas in Hip-Hop culture, offering a conference forum complete with competitions, performances, panels, workshops, and a marketplace for consumer friendly products marketed toward the Hip-Hop community. Never content with success, The B-boy Summit continues its mission to bring the hottest street dance, art, and music above ground to the masses. The B-boy Summit has grown into an internationally acclaimed 3 day festival incorporating all aspects of Hip-Hop in different plateaus, including the most intense battles, rawest circles, theatre performances, a DJ/MC Talent Showcase and live aerosol art painting. The B-boy Summit was created in 1994 out of the need for a community orientated Hip-Hop event that encompassed knowledge of the history of Hip-Hop culture and the skills of B-boying and B-girling. At that point in time B-boys and B-girls didn’t have a platform in which to come together, dance and pay homage to the traditional dance of Hip-Hop. Each year the event has expanded to encompass B-boys, B-girls, MCs, Aerosol Artists, and DJs from across the globe, steadily building into what is now the foremost Hip-Hop cultural event in the world. More recently, The Summit has become one of the most important events for Lockers, Poppers, Freestyle and House Dancers to take part in during The Summit’s Funk Fest. -

Table of Contents General Information Locking and Unlocking Seat And

Div: Out put date: April 3, 2001 Table of contents General information Locking and unlocking Seat and seat belts Instruments and controls Starting and driving For pleasant driving Vehicle care For emergencies Maintenance Specifications Div: Out put date: Overview - Instruments and Controls EB21AOHc 1- Front fog lamp switch* → P.4-22 Rear fog lamp switch → P.4-22 2- Electric remote-controlled outside rear-view mirror switch* → P.5-51 LHD 3- Combination headlamps, dipper and turn signal switch → P.4-14 Headlamp washer switch* → P.4-19 4- Supplemental restraint system-air bag (for driver’s seat) → P.3-42 Horn switch → P.4-24 5- Ignition switch → P.5-11 6- Auto-speed (cruise) control lever* → P.5-53 7- Meter and gauges → P.4-2 8- Windscreen wiper and washer switch → P.4-17 Rear window wiper and washer switch → P.4-19 9- Headlamp levelling switch → P.4-16 10- Rheostat (meter illumination control) → P.4-23 11- Fuse box lid → P.8-28 12- Bonnet release lever → P.2-9 13- Fuel tank filler door release lever → P.5-4 B21A600T Div: Out put date: Instruments and Controls 14- Parking brake lever → P.5-42 15- Audio* → P.6-2, 6-17 16- Hazard warning flasher switch → P.4-20 LHD 17- Multi centre display* → P.4-27 18- RV meter* → P.4-40 19- Rear window demister switch → P.4-21 20- Front heater/Manual air conditioning* → P.6-36 Front automatic air conditioning* → P.6-43 21- Ventilators → P.6-35 22- Supplemental restraint system-air bag* (for front passenger’s seat) → P.3-42 23- Ashtray (for front seats) → P.6-60 24- Cigarette lighter → P.6-59 25- Heated seat -

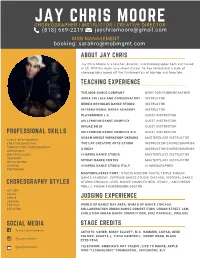

JAY CHRIS MOORE CHOREOGRAPHER I INSTRUCTOR I CREATIVE DIRECTOR (818) 669-2219 [email protected] MOB MANAGEMENT Booking: [email protected] ABOUT JAY CHRIS

JAY CHRIS MOORE CHOREOGRAPHER I INSTRUCTOR I CREATIVE DIRECTOR (818) 669-2219 [email protected] MOB MANAGEMENT booking: [email protected] ABOUT JAY CHRIS Jay Chris Moore is a teacher, director, and choreographer born and raised in LA. With his roots as a street dancer, he has formulated a style of choreography based off the fundamentals of hip hop and freestyle. TEACHING EXPERIENCE THE MOB DANCE COMPANY DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER AMDA COLLEGE AND CONSERVATORY INSTRUCTOR DEBBIE REYNOLDS DANCE STUDIO INSTRUCTOR INTERNATIONAL DANCE ACADEMY INSTRUCTOR PLAYGROUND L.A. GUEST INSTRUCTOR MILLENNIUM DANCE COMPLEX GUEST INSTRUCTOR KINJAZ DOJO GUEST INSTRUCTOR PROFESSIONAL SKILLS MILLENNIUM DANCE COMPLEX O.C. GUEST INSTRUCTOR URBAN MOVES WORKSHOP UKRAINE MASTERCLASS INSTRUCTOR ARTIST DEVELOPMENT CREATIVE DIRECTING THE LAB CREATIVE ARTS STUDIO INSTRUCTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER COMPETITION CHOREOGRAPHY STEEZY INSTRUCTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER WORKSHOPS MASTERCLASSES CHAPKIS DANCE STUDIO MASTERCLASS INSTRUCTOR SEMINARS MYWAY DANCE CENTRE MASTERCLASS INSTRUCTOR MUSIC MIXING STAGING CHAPKIS DANCE STUDIO ITALY CHOREOGRAPHER COSTUMING MASTERCLASSES CONT.: STUDIO MISSION TOKYO, TRIPLE THREAT D ANCE ACADEMY, SUPREME DANCE STUDIO CHICAGO, VISCERAL DANCE CHOREOGRAPHY STYLES S TUDIO CHICAGO, LEVEL DANCE COMPLEX NEW JERSEY, I AM PHRESH PHILLY, PHUNK PHENOMENON BOSTON HIP HOP KRUMP HOUSE JUDGING EXPERIENCE LOCKING POPPING WORLD OF DANCE BAY AREA, WORLD OF DANCE CHICAGO, BREAKING COLLABORATION URBAN DANCE COMPETITION, URBAN STREET JAM, EVOLUTION URBAN DANCE COMPETITION, KIDZ CARNIVAL, PRELUDE SOCIAL MEDIA STAGE CREDITS fb.me/jaychrismoore ARTISTS: USHER, MISSY ELLIOTT, M.C. HAMMER, LMFAO, KEKE PALMER, SHARYA J, TISHA CAMPBELL, SNOOP DOGG, BLACK @jaychrismoore EYED PEAS @jaychrismoore TELEVISION: AMERICA'S GOT TALENT, LIVE TO DANCE, APPLE IPOD "TECHNOLOGIC" COMMERCIAL, SUPERBOWL XLV . -

Josh Williams

953 N COLE AVE HOLLYWOOD, CA 90038 TEL: 323-957-6680 Cell Phone: 323-680-3858 JOSH WILLIAMS NON-UNION HEIGHT: 5’9 EYES: Brown HAIR: Black TELEVISION TEEN CHOICE AWARDS (FOX) DANCER AMY ALLEN THE FLAMA (CHACHI GONZALES) DANCER WILLDABEAST SO YOU THINK YOU CAN DANCE DANCER NYGEL LYTHGOE STAGE/LIVE PERFORMANCE TEEN CHOICE AWARDS (JASON DERULO) DANCER AMY ALLEN ROSHON (CONCERT) DANCER ROSERO MCCOY THE W HOTEL DANCER ANZE SKRUBE CLUB JETE (TIFFANY BILLINGS) DANCER JOSH WILLIAMS 8TH WONDER DANCER JOSH WILLIAMS CARNIVAL 2014 (TIGHT EYEZ) DANCER TIGHT EYEZ CARNIVAL 2014 (WILLDABEAST) DANCER WILLDABEAST CARNIVAL 2014 (ANTOINE TROUPE) DANCER ANTOINE TROUPE WORLD OF DANCE “SEATTLE 2013” (3rd) DANCER MYRON MARTEN WORLD OF DANCE “BAY AREA 2013” DANCER MYRON MARTEN WORLD OF DANCE “BAY AREA 2012” DANCER MYRON MARTEN UNRATED 2013 DANCER KOLANIE MARKS YTF GLOBAL TOUR YOUTUBE DANCER D-TRIX MUSIC VIDEOS TANK – DANCE WITH ME (LOVE STEP) DANCER ZENA FOSTER TANK – YOU’RE MY STAR DANCER GALEN HOOKS E-40 T.I. CHRIS BROWN – EPISODE DANCER ANTOINE TROUPE E-40 – BAMBOO DANCER FEATURED PHARELL WILLIAMS – HAPPY DANCER FEATURED JASON DERULO – TRUMPETS DANCER FEATURED MATT KEARNY – HEARTBEAT DANCER FEATURED CHIP CHOCOLATE – COOKIE DANCE DANCER FEATURED BRETT KISSEL – RAISE YOUR GLASS DANCER FEATURED COMMERCIALS DESPERADO BEER COMMERCIAL DANCER FEATURED COMEDY CENTRAL PROMO “MARTY PARTY” DANCER FEATURED TIME WARNER CABLE DANCER FEATURED SPECIAL SKILLS HIP HOP, BONE BREAKING, KRUMP, HOUSING, BREAKING, BASKETBALL, FOOTBALL, TRACK & FIELD, BASEBALL, ROLLERBLADING, SWIMMING, BIKING, TRICKING, TURFING, POPPING,TUTTING,WAVING. . -

Danc-Dance (Danc) 1

DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 DANC 1131. Introduction to Ballroom Dance DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 Credit (1) Introduction to ballroom dance for non dance majors. Students will learn DANC 1110G. Dance Appreciation basic ballroom technique and partnering work. May be repeated up to 2 3 Credits (3) credits. Restricted to Las Cruces campus only. This course introduces the student to the diverse elements that make up Learning Outcomes the world of dance, including a broad historic overview,roles of the dancer, 1. learn to dance Figures 1-7 in 3 American Style Ballroom dances choreographer and audience, and the evolution of the major genres. 2. develop rhythmic accuracy in movement Students will learn the fundamentals of dance technique, dance history, 3. develop the skills to adapt to a variety of dance partners and a variety of dance aesthetics. Restricted to: Main campus only. Learning Outcomes 4. develop adequate social and recreational dance skills 1. Explain a range of ideas about the place of dance in our society. 5. develop proper carriage, poise, and grace that pertain to Ballroom 2. Identify and apply critical analysis while looking at significant dance dance works in a range of styles. 6. learn to recognize Ballroom music and its application for the 3. Identify dance as an aesthetic and social practice and compare/ appropriate dances contrast dances across a range of historical periods and locations. 7. understand different possibilities for dance variations and their 4. Recognize dance as an embodied historical and cultural artifact, as applications to a variety of Ballroom dances well as a mode of nonverbal expression, within the human experience 8. -

Hip Hop Dance: Performance, Style, and Competition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank HIP HOP DANCE: PERFORMANCE, STYLE, AND COMPETITION by CHRISTOPHER COLE GORNEY A THESIS Presented to the Department ofDance and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofFine Arts June 2009 -------------_._.. _--------_...._- 11 "Hip Hop Dance: Performance, Style, and Competition," a thesis prepared by Christopher Cole Gorney in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master ofFine Arts degree in the Department ofDance. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Jenife .ning Committee Date Committee in Charge: Jenifer Craig Ph.D., Chair Steven Chatfield Ph.D. Christian Cherry MM Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School 111 An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Christopher Cole Gorney for the degree of Master ofFine Arts in the Department ofDance to be taken June 2009 Title: HIP HOP DANCE: PERFORMANCE, STYLE, AND COMPETITION Approved: ----- r_---- The purpose ofthis study was to identify and define the essential characteristics ofhip hop dance. Hip hop dance has taken many forms throughout its four decades ofexistence. This research shows that regardless ofthe form there are three prominent characteristics: performance, personal style, and competition. Although it is possible to isolate the study ofeach ofthese characteristics, they are inseparable when defining hip hop dance. There are several genre-specific performance formats in which hip hop dance is experienced. Personal style includes the individuality and creativity that is celebrated in the hip hop dancer. Competition is the inherent driving force that pushes hip hop dancers to extend the form's physical limitations. -

Updated 2020-21 IDT Faculty

MEET THE IDT FACULTY! Allison Kelly Allison is IDT’s new tap teacher and she is beyond thrilled to join the IDT family. Her love for dance began at a young age under the tutelage of Anita Johnstone, owner of Highland Dance Academy and she continued studying the Royal Academy Dance techniques until graduating high school in 2016. Along the way, Allison discovered her home within the jazz and tap world through dancing with Kelsey Ruth and Sarah Bordenet at Cascade Dance Academy. Allison taught ballet, tap, and jazz at HDA during her final two years of high school and throughout college. Allison recently graduated with a Bachelors of the Fine Arts in Dance at Seattle’s Cornish College. Please help us in welcoming Allison to the IDT family. Dakota Harwood Dakota joins IDT to teach Jazz, Contemporary & Acro as well as choreograph for our Performing Group. Dancer, photographer, and makeup artist Dakota Elizabeth got her start in Seattle and is thrilled to be returning to her hometown as an educator. She began as a state-ranked gymnast at Gymnastics East before transitioning to dance. Dakota trained primarily at Premiere Dance Center, Westlake, and The Connection (now KreativMndz), specializing in contemporary, hip hop, and tap. She learned from some of the industry’s brightest including Daniel Cruz, Kolanie Marks, Cameron Lee, Melissa Farrar, and Josh Scribner. After earning her degree from the University of Washington, Dakota moved to Los Angeles where she worked as a photographer and makeup artist for companies such as Break the Floor and several independent films. -

Talking Black Dance: Inside Out

CONVERSATIONS ACROSS THE FIELD OF DANCE STUDIES Talking Black Dance: Inside Out OutsideSociety of Dance InHistory Scholars 2016 | Volume XXXVI Table of Contents A Word from the Guest Editors ................................................4 The Mis-Education of the Global Hip-Hop Community: Reflections of Two Dance Teachers: Teaching and In Conversation with Duane Lee Holland | Learning Baakasimba Dance- In and Out of Africa | Tanya Calamoneri.............................................................................42 Jill Pribyl & Ibanda Grace Flavia.......................................................86 TALKING BLACK DANCE: INSIDE OUT .................6 Mackenson Israel Blanchard on Hip-Hop Dance Choreographing the Individual: Andréya Ouamba’s Talking Black Dance | in Haiti | Mario LaMothe ...............................................................46 Contemporary (African) Dance Approach | Thomas F. DeFrantz & Takiyah Nur Amin ...........................................8 “Recipe for Elevation” | Dionne C. Griffiths ..............................52 Amy Swanson...................................................................................93 Legacy, Evolution and Transcendence When Dance Voices Protest | Dancing Dakar, 2011-2013 | Keith Hennessy ..........................98 In “The Magic of Katherine Dunham” | Gregory King and Ellen Chenoweth .................................................53 Whiteness Revisited: Reflections of a White Mother | Joshua Legg & April Berry ................................................................12 -

Vidéos Danse Documentaire (2012)

Vidéos Danse Documentaire 2012 2 MÉDIATHÈQUE DE LA MEINAU La Médiathèque de la Meinau vous propose un espace consacré aux Arts du spectacle vivant et développe un fonds important de documents sur la danse, le cirque, le théâtre, l'humour, les comédies musicales, le cinéma et la musique. Vous y trouverez des DVD, des VHS, des CD, des livres, des magazines et des CD-ROM. Nos documents recouvrent tous les types de danse : contemporaine, classique, urbaine, du monde. Dépositaire à sa création du fonds Images de la Culture/danse , la Médiathèque complète ce fonds par des documents du catalogue du Centre National de la Culture, et de l'ensemble de la production actuelle. Plus de 500 vidéos constituent aujourd'hui le fonds, proposées en consultation sur place et/ou à emprunter. La majorité des vidéos est empruntable. Vous trouverez une indication supplémentaire pour les documents consultables sur place. A ce fonds audiovisuel s’ajoutent des magazines spécialisés empruntables, des CD de musique chorégraphique, ainsi que 200 livres pour un public adulte et jeune : histoires de la danse, biographies de danseurs et chorégraphes, ouvrages théoriques sur les pratiques de la danse. Deux espaces de consultation sont mis à votre disposition pour visionner sur place les vidéos du fonds. Les groupes et les classes peuvent réserver la salle d'animation pour une projection collective. Les Samedis de la danse Depuis septembre 2006, l'équipe de la Médiathèque a mis en place un rendez-vous mensuel pour les amoureux ou curieux de la danse. Chaque troisième samedi du mois, à 15h, une projection est organisée pour vous faire découvrir un artiste, un spectacle ou un genre particulier. -

Year of Dance!”

“Another Great Year of Dance!” Rugcutterz Danz Artz EXtravaganza! 2009 YEARBOOK A Message From SPECTACULAR SPA SPECIALS Enjoy Spa’z Classical Esthetics all Year Long for one low price - choose from five incredible beauty packages!* The Silky Skin Package The Skin Glow Package Pampered Hands and WAXING FACIALS Feet Package Unlimited for 1 Year! Buy 3, Get 3 FREE! Full Leg & Bikini, Underarms, Arms, 12 Pedicures and 24 Manicures Eyebrow & Upper Lip, Back Regular $600 SAVE $300 Regular $1,080 SAVE $781 Regular $1,984 SAVE $1,685 $ 99* $ 99* $ 99* Only 299 Only 299 Only 299 Regular price based on 12 Full Leg & Bikini, 24 Underarms,12 Arms, 24 Eyebrow, 24 Upper Lip, 4 Back (Classic or Beauty Lift Only) excluding Microdermabrasion Classic Skin Renewal Package The Ultimate Skin Therapy Package 80 SESSIONS Regular $2,800 SAVE $1,800 $ 99* LASERLIFE COLD LASER THERAPY MICRODERMABRASION Only 999 The non-surgical option to enhancing your skin tone and improve the appearance of Buy 3, Get 3 FREE! scars and other skin conditions. 40 SESSIONS Regular $1,400 SAVE $800 Treatment areas to include: Facial Firming and Toning, Cellulite Reduction, Breast Regular $900 SAVE $450 Lifting, Arm and Thigh Toning. $ 99* Only 599 * 20 SESSIONS Regular $700 SAVE $400 Reveal $ 99 younger looking skin Only449 $ 99* *Regular price based on $150 per session. Only 299 RECEIVE A 20% DISCOUNT ON ALL OUR EXCEL OR BIODROGA PRODUCTS WITH THE PURCHASE OF ANY PACKAGE *All packages include 20% off all skin care products at Spa'z Classical Esthetics. Packages are valid for 1 year from the date of purchase and are non-transferable. -

Streetdance and Hip Hop - Let's Get It Right!

STREETDANCE AND HIP HOP - LET'S GET IT RIGHT! Article by David Croft, Freelance Dance Artist OK - so I decided to write this article after many years studying various styles of Street dance and Hip Hop, also teaching these styles in Schools, Dance schools and in the community. Throughout my years of training and teaching, I have found a lack of understanding, knowledge and, in some cases, will, to really search out the skills, foundation and blueprint of these dances. The words "Street Dance" and "Hip Hop" are widely and loosely used without a real understanding of what they mean. Street Dance is an umbrella term for various styles including Bboying or breakin (breakin is an original Hip Hop dance along with Rockin and Party dance – the word break dance did not exist in the beginning, this was a term used by the media, originally it was Bboying. (Bboy, standing for Break boy, Beat boy or Bronx boy)…….for more click here Conquestcrew Popping/Boogaloo Style was created by Sam Soloman and Popping technique involves contracting your muscles to the music using your legs, arms, chest and neck. Boogaloo has a very funky groove constantly using head and shoulders. It also involves rolling the hips and knees. Locking was created by Don Campbell. This involves movements like wrist twirls, points, giving himself “5”, locks (which are sharp stops), knee drops and half splits. (Popping/Boogaloo and Locking are part of the West Coast Funk movement ). House Dance and Hip Hop. With Hip Hop coming out of the East Coast (New York) and West Coast Funk from the west (California) there was a great collaboration in cultures bringing the two coasts together. -

Hip Hop Terms

1 Topic Page Number General Hip Hop Definitions ………………………………………………. 3 Definitions Related to Specific Dance Styles: ♦ Breaking ………………………………………………………………………. 4 ♦ House ………………………………………………………..………………… 6 ♦ Popping / Locking …………………………………………….….……… 7 2 GENERAL • Battle A competition in which dancers, usually in an open circle surrounded by their competitors, dance their routines, whether improvised (freestyle) or planned. Participants vary in numbers, ranging from one on one to battles of opposing breaking crews, or teams. Winners are determined by outside judges, often with prize money. • • Cypher Open forum, mock exhibitions. Similar to battles, but less emphasis on competition. • Freestyle Improvised Old School routine. • Hip Hop A lifestyle that is comprised of 4 elements: Breaking, MCing, DJing, and Graffiti. Footwear and clothing are part of the hip hop style. Much of it is influenced by the original breaking crews in the 1980’s from the Bronx. Sneakers are usually flat soled and may range from Nike, Adidas, Puma, or Converse. Generally caps are worn for spins, often with padding to protect the head. To optimize the fast footwork and floor moves, the baggy pants favored by hip hop rappers are not seen. o Breaking Breakdancing. o MCing Rapping. MC uses rhyming verses, pre‐written or freestyled, to introduce and praise the DJ or excite the crowd. o DJing Art of the disk jockey. o Graffiti Name for images or lettering scratched, scrawled, painted usually on buildings, trains etc. • Hip Hop dance There are two main categories of hip hop dance: Old School and New School. • New School hip hop dance Newer forms of hip hop music or dance (house, krumping, voguing, street jazz) that emerged in the 1990s • Old School hip hop dance Original forms of hip hop music or dance (breaking, popping, and locking) that evolved in the 1970s and 80s.