Travels of a Collector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2015-16.Pdf

CONTENTS Office Bearers 1 President’s Report 2 Finance Report 6 Profit & Loss Statement 6 Balance Sheet 9 Notes to the Financial Reports 10 Independent Audit Report to Members 11 Declaration by Members of the Committee 12 Acknowledgements 13 Club Supporters 14 Club Coach: Season Review 15 1st XI: Season Review 23 1st XI: Award Winners 25 1st XI: Season Statistics 25 Batting 25 Bowling 25 2nd XI: Season Review 26 2nd XI: Award Winners 29 2nd XI: Season Statistics 29 Batting 29 Bowling 30 3rd XI: Award Winners 31 3rd XI: Season Statistics 31 Batting 31 i Bowling 32 4th XI: Award Winners 33 4th XI: Season Statistics 33 Batting 33 Bowling 34 Award Winners 35 Outstanding Performances 37 Batting 37 Bowling 37 Honour Roll 38 Honorary Life Members 43 Hall of Fame & Club Legends 43 Club History 44 ii Office Bearers President – Graeme Cook Treasurer – Alex Steenberg Secretary – Alice Barrow Committee Members Mike Delves, Stephen Stanley, Wayne Stewart, Leigh Watts Cricket Victoria Delegate Graeme Cook, Leigh Watts (Alternate) Cricket Sub-Committee Jeff Harvey (Chair), Alan Melbourne (Secretary), Graeme Cook, Peter Dickson, Phil Lovell, Michael O’Sullivan Hall of Fame Sub-Committee Jeff Harvey (Chair), Alan Melbourne (Secretary), Denis de Lacy, Rob Goldin, George Murray, Roger Page, Ralston Wood 1 Presidents Report The 2015/16 season marked the 30th anniversary of the merged Fitzroy Doncaster Cricket Club and it will remain etched in our memories for a very long time. Winning a First XI premiership is an outstanding achievement by any measure and one that everyone involved with our Club can be proud of and celebrate. -

Charles Kelleway Passed Away on 16 November 1944 in Lindfield, Sydney

Charle s Kelleway (188 6 - 1944) Australia n Cricketer (1910/11 - 1928/29) NS W Cricketer (1907/0 8 - 1928/29) • Born in Lismore on 25 April 1886. • Right-hand bat and right-arm fast-medium bowler. • North Coastal Cricket Zone’s first Australian capped player. He played 26 test matches, and 132 first class matches. • He was the original captain of the AIF team that played matches in England after the end of World War I. • In 26 tests he scored 1422 runs at 37.42 with three centuries and six half-centuries, and he took 52 wickets at 32.36 with a best of 5-33. • He was the first of just four Australians to score a century (114) and take five wickets in an innings (5/33) in the same test. He did this against South Africa in the Triangular Test series in England in 1912. Only Jack Gregory, Keith Miller and Richie Benaud have duplicated his feat for Australia. • He is the only player to play test cricket with both Victor Trumper and Don Bradman. • In 132 first-class matches he scored 6389 runs at 35.10 with 15 centuries and 28 half-centuries. With the ball, he took 339 wickets at 26.33 with 10 five wicket performances. Amazingly, he bowled almost half (164) of these. He bowled more than half (111) of his victims for New South Wales. • In 57 first-class matches for New South Wales he scored 3031 runs at 37.88 with 10 centuries and 11 half-centuries. He took 215 wickets at 23.90 with seven five-wicket performances, three of these being seven wicket hauls, with a best of 7-39. -

Issue 43: Summer 2010/11

Journal of the Melbourne CriCket Club library issue 43, suMMer 2010/2011 Cro∫se: f. A Cro∫ier, or Bi∫hops ∫taffe; also, a croo~ed ∫taffe wherewith boyes play at cricket. This Issue: Celebrating the 400th anniversary of our oldest item, Ashes to Ashes, Some notes on the Long Room, and Mollydookers in Australian Test Cricket Library News “How do you celebrate a Quadricentennial?” With an exhibition celebrating four centuries of cricket in print The new MCC Library visits MCC Library A range of articles in this edition of The Yorker complement • The famous Ashes obituaries published in Cricket, a weekly cataloguing From December 6, 2010 to February 4, 2010, staff in the MCC the new exhibition commemorating the 400th anniversary of record of the game , and Sporting Times in 1882 and the team has swung Library will be hosting a colleague from our reciprocal club the publication of the oldest book in the MCC Library, Randle verse pasted on to the Darnley Ashes Urn printed in into action. in London, Neil Robinson, research officer at the Marylebone Cotgrave’s Dictionarie of the French and English tongues, published Melbourne Punch in 1883. in London in 1611, the same year as the King James Bible and the This year Cricket Club’s Arts and Library Department. This visit will • The large paper edition of W.G. Grace’s book that he premiere of Shakespeare’s last solo play, The Tempest. has seen a be an important opportunity for both Neil’s professional presented to the Melbourne Cricket Club during his tour in commitment development, as he observes the weekday and event day The Dictionarie is a scarce book, but not especially rare. -

Meet... Don Bradman Ebook Free Download

MEET... DON BRADMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Coral Vass | 32 pages | 01 Aug 2016 | Random House Australia | 9781925324891 | English | North Sydney, Australia Meet... Don Bradman PDF Book Teenager who killed 82yo in random, unprovoked bashing pleads for forgiveness. Federer may miss first Australian Open in more than two decades, hints at retirement Posted 3 h hours ago Mon Monday 14 Dec December at am. Straight to your inbox. And this was one of the secrets of his astonishing success with the bat. The former cricketer has taken it upon himself to study and decode Bradman's unorthodox grip and backlift. A simple looking man who introduced himself as "Don" met them at the airport. Enter your email to sign up. Treehouse Fun Book. Abhishek Mukherjee looks at the first magical moment in Indo-Australian sport relationship. Allan Ahlberg , Janet Ahlberg. You can find out more by clicking this link Close. We will have the opportunity of learning something from them. I personally look forward to emulating Sir Donald, in leaving the game in better shape for having been a part of it. No One Likes a Fart. As far as I'm concerned, he's simply the greatest sportsman the world has ever seen," he said. Each Peach Pear Plum. Book With No Pictures. Colossal Book of Colours. Books, Bauer. One can go on for pages on the legend, but this, unfortunately, is a cricket website, so let us revert to the incident in question. Now under cricketer Baheer Shah has come into the limelight for his exceptional batting average, which is even more than the legendary Sir Don Bradman. -

Roger Page Cricket Books

ROGER PAGE DEALER IN NEW AND SECOND-HAND CRICKET BOOKS 10 EKARI COURT, YALLAMBIE, VICTORIA, 3085 TELEPHONE: (03) 9435 6332 FAX: (03) 9432 2050 EMAIL: [email protected] ABN 95 007 799 336 OCTOBER 2016 CATALOGUE Unless otherwise stated, all books in good condition & bound in cloth boards. Books once sold cannot be returned or exchanged. G.S.T. of 10% to be added to all listed prices for purchases within Australia. Postage is charged on all orders. For parcels l - 2kgs. in weight, the following rates apply: within Victoria $14:00; to New South Wales & South Australia $16.00; to the Brisbane metropolitan area and to Tasmania $18.00; to other parts of Queensland $22; to Western Australia & the Northern Territory $24.00; to New Zealand $40; and to other overseas countries $50.00. Overseas remittances - bank drafts in Australian currency - should be made payable at the Commonwealth Bank, Greensborough, Victoria, 3088. Mastercard and Visa accepted. This List is a selection of current stock. Enquiries for other items are welcome. Cricket books and collections purchased. A. ANNUALS AND PERIODICALS $ ¢ 1. A.C.S International Cricket Year Books: a. 1986 (lst edition) to 1995 inc. 20.00 ea b. 2014, 2015, 2016 70.00 ea 2. Athletic News Cricket Annuals: a. 1900, 1903 (fair condition), 1913, 1914, 1919 50.00 ea b. 1922 to 1929 inc. 30.00 ea c. 1930 to 1939 inc. 25.00 ea 3. Australian Cricket Digest (ed) Lawrie Colliver: a. 2012-13, 2013-14, 2014-15, 25.00 ea. b. 2015-2016 30.00 ea 4. -

CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1928-1948 - the Bradman Era

Page:1 Nov 25, 2018 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1928-1948 - The Bradman Era Lot 2072 2072 1930 Victor Richardson's Ashes Medal sterling silver with Australian Coat-of-Arms & 'AUSTRALIAN ELEVEN 1930' on front; on reverse 'Presented to the Members of the Australian Eleven in Commemoration of the Recovery of The Ashes 1930, by General Motors Australia Pty Limited', engraved below 'VY Richardson', in original presentation case. [Victor Richardson played 19 Tests between 1927-36, including five as Australian captain; he is the grandfather of Ian, Greg & Trevor Chappell] 3,000 Lot 2073 2073 1934 Australian Team mounted photograph signed by the entire squad (19) including Don Bradman, Bill Woodfull, Clarrie Grimmett & Bill Ponsford, framed & glazed, overall 52x42cm. 1,500 Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au Nov 25, 2018 CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1928-1948 - The Bradman Era (continued) Lot Type Grading Description Est $A Lot 2074 2074 1934 'In Quest of the Ashes 1934 - The Don Bradman Souvenir Booklet and Scoring Records', published by Wrigleys, with the scarce scoring sheet, and also a letter from Wrigleys to the previous owner, explaining he needed to send 30 wrappers before they would despatch the Cricket Book. 200 Lot 2075 2075 1935-36 Australian Team photograph from South African Tour with 16 signatures including Victor Richardson, Stan McCabe, Bert Oldfield & Bill O'Reilly, overall 39x34cm, couple of spots on photo & some soiling, signatures quite legible. [Australia won the five-Test series 4-0] 400 2076 1936 'The Ashes 1936-1937 - The Wrigley Souvenir Book and Scoring Records', published by Wrigley's, with the scarce scoring sheet completed by the previous owner, front cover shows the two opposing captains Don Bradman & Gubby Allen, some faults. -

Extract Catalogue for Auction

Page:1 May 19, 2019 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1949 Onwards Ex Lot 94 94 1955-66 Melbourne Cricket Club membership badges complete run 1955-56 to 1965-66, all the scarce Country memberships. Very fine condition. (11) 120 95 1960 'The Tied Test', Australia v West Indies, 1st Test at Brisbane, display comprising action picture signed by Wes Hall & Richie Benaud, limited edition 372/1000, window mounted, framed & glazed, overall 88x63cm. With CoA. 100 Lot 96 96 1972-73 Jack Ryder Medal dinner menu for the inaugural medal presentation with 18 signatures including Jack Ryder, Don Bradman, Bill Ponsford, Lindsay Hassett and inaugural winner Ron Bird. Very scarce. 200 Lot 97 97 1977 Centenary Test collection including Autograph Book with 254 signatures of current & former Test players including Harold Larwood, Percy Fender, Peter May, Clarrie Grimmett, Ray Lindwall, Richie Benaud, Bill Brown; entree cards (4), dinner menu, programme & book. 250 98 - Print 'Melbourne Cricket Club 1877' with c37 signatures including Harold Larwood, Denis Compton, Len Hutton, Ted Dexter & Ross Edwards; window mounted, framed & glazed, overall 75x58cm. 100 99 - Strip of 5 reserved seat tickets, one for each day of the Centenary Test, Australia v England at MCG on 12th-17th March, framed, overall 27x55cm. Plus another framed display with 9 reserved seat tickets. (2) 150 100 - 'Great Moments' poster, with signatures of captains Greg Chappell & Tony Greig, limited edition 49/550, framed & glazed, overall 112x86cm. 150 Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au May 19, 2019 CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1949 Onwards (continued) Lot Type Grading Description Est $A Ex Lot 101 101 1977-86 Photographs noted Australian team photos (6) from 1977-1986; framed photos of Ray Bright (6) including press photo of Bright's 100th match for Victoria (becoming Victoria's most capped player, overtaking Bill Lawry's 99); artworks of cricketer & two-up player. -

St George District Cricket Club Was Founded As a Subdistrict Club in 1911 Under the Auspices of the NSW Cricket Association, the President of St George DCC Being Mr J

St George District Cricket Club was founded as a subdistrict club in 1911 under the auspices of the NSW Cricket Association, the President of St George DCC being Mr J. Lister. Hurstville Oval at that time was not an enclosed ground - despite persistent pressure on the Council. The original area of Hurstville Park (of seven acres) was bought from the McMahon Estate in the early years of the century, and vested in the council. The ground was fenced, planted and developed by cricket lovers over a period of several years - and in 1911 famous Australian left-hander Warren Bardsley brought an invitation X1 to Hurstville Oval to play the St. George district team, on the official opening day. St George began playing in First Grade in 1921 and then competed in 1st, 2nd and 3rd grade competitions. They also entered teams in Shires competition in 1926 and continued to play teams in that competition from 1926 to 1947 and again from 1965 to 1968. A 4th grade team had begun to play in 1934 and has continued to the present with a break from 1940 to 1948. With the introduction of 5th grade in 1969 there was no further participation in the Shires competition. Currently, St George DCC Inc fields teams in the 1st to 5th grade competitions, the Poidevin-Gray Shield (Under 21), the A.W.Green Shield (Under 16) and the 1st Grade Limited Overs competition. St George’s best known player is of course Sir Donald Bradman who came to the club in 1926 and later stayed at the Rockdale home of then club secretary Mr F. -

Premier Cricket Awards Welcome Message

2016-17 PREMIER CRICKET AWARDS WELCOME MESSAGE What a season it has We applaud Essendon As the pathway to the state’s The 2016-17 season has been! Tonight is an (2nds), St Kilda (3rds) and elite cricket teams, we were been one to remember and important opportunity for Monash Tigers (4ths) who delighted to see a number I would like to take this celebration as we toast the claimed victory in the other of players debut over the opportunity on behalf of achievements of our best XIs. course of the season. everyone at Cricket Victoria performed players, clubs to congratulate all of our and officials in men’s and award winners. I’d also like to congratulate We especially congratulate women’s cricket over the Essendon Maribyrnong Seb Gotch (Melbourne), course of the summer. Park who won the Women’s Will Pucovski (Melbourne), Enjoy tonight and I look Premier Firsts title for a Evan Gulbis (Prahran), forward to seeing you all I congratulate Fitzroy sixth time. Marcus Harris (St Kilda), again next season. Doncaster, led by coach Makinley Blows (Essendon Mick O’Sullivan and captain Maribyrnong Park), Sophie Led by captain Briana Peter Dickson, on securing Molineux (Dandenong), Binch, the Bombers came WELCOME back to back titles with a Hayleigh Brennan (Box Hill) from fourth place on the hard-fought victory over and Alana King (Prahran) TO THE ladder to defeat Box Hill in Melbourne in the Men’s on making their maiden the final with Molly Strano Premier Firsts Final. Victorian appearances. 2016-17 claiming the Betty Wilson TONY DODEMAIDE Medal. -

Jack Marsh History Lecture 2015

JACK MARSH HISTORY LECTURE 2015 Written and delivered by Gideon Haigh Sydney Cricket Ground Wednesday 21 January 2015 JackHISTORY Marsh LECTURE “When he came he (2 opened the windows of the mind to a new vision of what batting could be” How Victor Trumper Changed Cricket Forever (1) My title, which seems to combine Aldous Huxley’s doors (1) Feline tribute: Gideon with his cat ‘Trumper’ of perception with Dusty Springfield’s windmills of your mind, is actually from a rather less exotic source, Johnnie Moyes. The journalist and broadcaster Moyes may be unique in tightness of affiliation with both Victor Trumper and Donald Bradman: he was an opponent of the former, a biographer of the latter, a friend and idolator of both. He also links the man in whose name tonight’s inaugural lecture has been endowed. Six-year-old Moyes first met Trumper one summer evening in December 1900 when his father, a schoolteacher, invited the visiting New South Wales team to their home in Adelaide. In The Changing Face of Cricket, Moyes recalled that he was at first less taken by Trumper than by his teammate Jack Marsh: “I do not remember now whether I had seen a coloured man, but certainly I hadn’t seen one who was playing first-class (2) Iconic image: the photo that began the Trumper legend cricket, and Marsh fascinated me. What a grand bowler he must have been!” It was only a few weeks later that Trumper and Marsh participated in the Federation Sports Carnival, finishing first and second in the competition for throwing a cricket ball here. -

Issue 40: Summer 2009/10

Journal of the Melbourne Cricket Club Library Issue 40, Summer 2009 This Issue From our Summer 2009/10 edition Ken Williams looks at the fi rst Pakistan tour of Australia, 45 years ago. We also pay tribute to Richie Benaud's role in cricket, as he undertakes his last Test series of ball-by-ball commentary and wish him luck in his future endeavours in the cricket media. Ross Perry presents an analysis of Australia's fi rst 16-Test winning streak from October 1999 to March 2001. A future issue of The Yorker will cover their second run of 16 Test victories. We note that part two of Trevor Ruddell's article detailing the development of the rules of Australian football has been delayed until our next issue, which is due around Easter 2010. THE EDITORS Treasures from the Collections The day Don Bradman met his match in Frank Thorn On Saturday, February 25, 1939 a large crowd gathered in the Melbourne District competition throughout the at the Adelaide Oval for the second day’s play in the fi nal 1930s, during which time he captured 266 wickets at 20.20. Sheffi eld Shield match of the season, between South Despite his impressive club record, he played only seven Australia and Victoria. The fans came more in anticipation games for Victoria, in which he captured 24 wickets at an of witnessing the setting of a world record than in support average of 26.83. Remarkably, the two matches in which of the home side, which began the game one point ahead he dismissed Bradman were his only Shield appearances, of its opponent on the Shield table. -

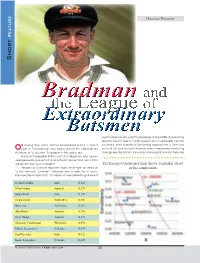

Feature Short

GANGAN PRATHAP Feature Short quality of performance (batting average) and quantity of performing opportunities (number of innings played). Sachin is probably the most N Boxing Day 2012, Kumar Sangakkara joined a select successful when quantity of performing opportunities is taken into O club of Test batsmen who had reached the extraordinary account. On quality of performance, when measured by the batting milestone of 10,000 runs. The players in this league are: average (we depart from the usual cricketing practice and here take Is Sachin the greatest in this club? Or is it Bradman, who had an average nearly double that of all in the list above? And, who of this galaxy, was the most consistent? The Exergy-Consistency map shows Tendulkar ahead Readers of Science Reporter might remember an exercise of the competition to find the most “consistent” batsmen from a select list of iconic batsmen (September 2011). “Consistency” was defined to go beyond Sachin Tendulkar India 15,645 Ricky Ponting Australia 13,378 Rahul Dravid India 13,288 Jacques Kallis South Africa 12,980 Brian Lara West Indies 11,953 Allan Border Australia 11,174 Steve Waugh Australia 10,927 Shivnarine Chanderpaul West Indies 10,696 Mahela Jayawardene Sri Lanka 10,674 Sunil Gavaskar India 10,122 Kumar Sangakkara Sri Lanka 10,045 SCIENCE REPORTER, FEBRUARY 2013 30 Short Feature This is a composite that combines quality and consistency along with quantity. If such an indicator is an acceptable measure for batting performance, then Tendulkar is once again ahead of the rest of the competition. Sachin is probably the most successful when quantity of performing opportunities is taken into account.