Your Sorrow Shall Be Turned Into Joy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quafter Concluded from Page 18

Quafter Concluded from page 18. Previous to the days of railways, when roads were bad and communication difficult and expensive, Friends did not often go far from home. Heads of families, sometimes accom panied by their sons and daughters, would occasionally go to the Quarterly Meetings, but we can see by the intermarriages of families that acquaintanceship and society were generally limited to those who resided in the neighbourhood. Thus, in a county, the centre of a Monthly Meeting, we find, say, half a dozen families whose members were continually intermarrying. In the County Wexford, for instance, situated as it is in a corner of the island, there were the families of Davis, Woodcock, Sparrow, Martin, Poole, Sandwith, Goff, and Chamberlin, who married and inter married again and again. Cork people married Cork people, and so it was in Limerick and in Waterford, to a degree which nowadays we do not realise. Marriages between Ulster and Munster were, in the eighteenth century, very uncommon. Dublin, naturally, was a kind of meeting- point, and its importance as the capital, and being the seat of the largest Monthly Meeting, led to many marriages there of couples of whom one at least resided in the country. The old rule of not allowing second cousins to be passed for marriage of course very much limited choice. So many in that relationship have been united since the rule was relaxed that, we may take it, if such alteration had not taken place, a dead lock and a break up would have occurred. While the change, and, perhaps, that of allowing first and second cousins4 also to many, can hardly be regretted, it is to be hoped that the latitude sanctioned by London Yearly Meeting as regards first cousins may continue to be forbidden in this country.5 All are agreed that as regards consanguinity 4 What we in this country understand by this term, is the relationship between a person and the child of his first cousin. -

Winckley Square Around Here’ the Geography Is Key to the History Walton

Replica of the ceremonial Roman cavalry helmet (c100 A.D.) The last battle fought on English soil was the battle of Preston in unchallenged across the bridge and began to surround Preston discovered at Ribchester in 1796: photo Steve Harrison 1715. Jacobites (the word comes from the Latin for James- town centre. The battle that followed resulted in far more Jacobus) were the supporters of James, the Old Pretender; son Government deaths than of Jacobites but led ultimately to the of the deposed James II. They wanted to see the Stuart line surrender of the supporters of James. It was recorded at the time ‘Not much history restored in place of the Protestant George I. that the Jacobite Gentlemen Ocers, having declared James the King in Preston Market Square, spent the next few days The Jacobites occupied Preston in November 1715. Meanwhile celebrating and drinking; enchanted by the beauty of the the Government forces marched from the south and east to women of Preston. Having married a beautiful woman I met in a By Steve Harrison: Preston. The Jacobites made no attempt to block the bridge at Preston pub, not far from the same market square, I know the Friend of Winckley Square around here’ The Geography is key to the History Walton. The Government forces of George I marched feeling. The Ribble Valley acts both as a route and as a barrier. St What is apparent to the Friends of Winckley Square (FoWS) is that every aspect of the Leonard’s is built on top of the millstone grit hill which stands between the Rivers Ribble and Darwen. -

St Mary's Catholic Church Chorley

CHORLEY HOSPITAL: Please contact St Joseph's Chorley (262713) if any member of your family is admitted into Chorley Hospital and needs a visit. In an emergency ask St Mary’s Catholic Church Chorley the staff to bleep the on-call priest. For the chaplaincy service at Royal Preston Hospital please ring 01772 522435, or in emergency please ask the staff to contact the on-call priest from St Clare’s Parish or elsewhere. FIFTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME th ST ANNE’S GUILD: next bingo is on 12 February at 19.45 in the Parish Centre. th 10 February 2019 ADVANCE NOTICE: Ash Wednesday: 6th March, Chrism Mass at Metropolitan Cathedral in Liverpool: Wednesday 17th April. Triduum: Holy Thursday 18th April. Jesus was standing one day by Good Friday 19th April. Easter Saturday: 20th April. Easter Sunday 21st April. Divine the Lake of Gennesaret, with the Mercy Sunday 28th April. There will be a coach travelling to the Chrism Mass, as crowd pressing round him usual. Details will be announced at the beginning of April. listening to the word of God, Please note: This year there will be only ONE Reconciliation Service for the when he caught sight of two Deanery. Please pass the word around. Details will follow. boats close to the bank. The fishermen had gone out of them O Dear Jesus, and were washing their nets. He I humbly implore You to grant Your special graces to our family. got into one of the boats – it was May our home be the shrine of peace, purity, love, labour and faith. -

Bolderboulder 2005 - Bolderboulder 10K - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

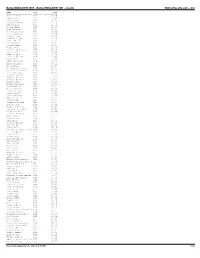

BolderBOULDER 2005 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Michael Aish M28 30:29 Jesus Solis M21 30:45 Nelson Laux M26 30:58 Kristian Agnew M32 31:10 Art Seimers M32 31:51 Joshua Glaab M22 31:56 Paul DiGrappa M24 32:14 Aaron Carrizales M27 32:23 Greg Augspurger M27 32:26 Colby Wissel M20 32:36 Luke Garringer M22 32:39 John McGuire M18 32:42 Kris Gemmell M27 32:44 Jason Robbie M28 32:47 Jordan Jones M23 32:51 Carl David Kinney M23 32:51 Scott Goff M28 32:55 Adam Bergquist M26 32:59 trent r morrell M35 33:02 Peter Vail M30 33:06 JOHN HONERKAMP M29 33:10 Bucky Schafer M23 33:12 Jason Hill M26 33:15 Avi Bershof Kramer M23 33:17 Seth James DeMoor M19 33:20 Tate Behning M23 33:22 Brandon Jessop M26 33:23 Gregory Winter M26 33:25 Chester G Kurtz M30 33:27 Aaron Clark M18 33:28 Kevin Gallagher M25 33:30 Dan Ferguson M23 33:34 James Johnson M36 33:38 Drew Tonniges M21 33:41 Peter Remien M25 33:45 Lance Denning M43 33:48 Matt Hill M24 33:51 Jason Holt M18 33:54 David Liebowitz M28 33:57 John Peeters M26 34:01 Humberto Zelaya M30 34:05 Craig A. Greenslit M35 34:08 Galen Burrell M25 34:09 Darren De Reuck M40 34:11 Grant Scott M22 34:12 Mike Callor M26 34:14 Ryan Price M27 34:15 Cameron Widoff M35 34:16 John Tribbia M23 34:18 Rob Gilbert M39 34:19 Matthew Douglas Kascak M24 34:21 J.D. -

Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper

Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper Notes Contents 1 Visiting the Exhibition 2 The Exhibition 3 Answers to the Trail Page 1 – Family Tree Page 2 – 1689 (James VII and II) Page 3 – 1708 (James VIII and III) Page 4 – 1745 (Bonnie Prince Charlie) 4 After your visit 5 Additional Resources National Museums Scotland Scottish Charity, No. SC011130 illustrations © Jenny Proudfoot www.jennyproudfoot.co.uk Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper Notes 1 Introduction Explore the real story of Prince Charles Edward Stuart, better known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, and the rise and fall of the Jacobites. Step into the world of the Royal House of Stuart, one dynasty divided into two courts by religion, politics and war, each fighting for the throne of thethree kingdoms of Scotland, England and Ireland. Discover how four Jacobite kings became pawns in a much wider European political game. And follow the Jacobites’ fight to regain their lost kingdoms through five challenges to the throne, the last ending in crushing defeat at the Battle of Culloden and Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape to the Isle of Skye and onwards to Europe. The schools trail will help your class explore the exhibition and the Jacobite story through three key players: James VII and II, James VIII and III and Bonnie Prince Charlie. 1. Visiting the Exhibition (Please share this information with your adult helpers) Page Character Year Exhibition sections Important information 1 N/A N/A The Stuart Dynasty and the Union of the Crowns • Food and drink is not permitted 2 James VII 1688 Dynasty restored, Dynasty • Photography is not allowed and II divided, A court in exile • When completing the trail, ensure pupils use a pencil 3 James VIII 1708- The challenges of James VIII and III 1715 and III, All roads lead to Rome • You will enter and exit via different doors. -

Insert Document Title What's New in England 2015 and Beyond for The

Insert Document Title Here What’s New in England 2015 and Beyond For the most up to date guide, please check: http://www.visitengland.org/media/resources/whats_new.aspx 1. Accommodation Bouja by Hoseasons, Devon and Hampshire From 30 January Hoseasons will be introducing ‘affordable luxury breaks’ under new brand Bouja. Set across six countryside and coastal locations, Bouja will offer holiday homes with a deck, patio or private garden, as well as amenities including a flat-screen TV. Bike hire, nature trails and great quality bistros and restaurants will be offered nearby, while quirkier spaces will be provided by the designer Bouja Boutique. Beach Cove Coastal Retreat will be the first location to open, with others following throughout Q1. http://www.hoseasons.co.uk/ The Hospital Club, London January The former hospital turned ‘creative hub’, The Hospital Club, has now added 15 hotel rooms to its Covent Garden venue. The rooms boast sumptuous interiors and stained glass by Russell Sage studios, providing guests with a home away from home. Suites also include a private terrace, rainforest showers and lounge area. Rooms start from £180 per night. http://www.thehospitalclub.com The 25 Boutique, Torquay January A luxury 5 star boutique B&B, is located a 10 minute walk from the centre of Torquay and close by to the Riviera International Centre and Torre abbey. Each room is individually designed and provides different sizes and amenities. http://www.the25.uk/ The Seaside Boarding House, Restaurant & Bar, Burton Bradstock February/March The Seaside Boarding House Restaurant and Bar is set on the cliffs overlooking the sweep of Dorset’s famous Chesil Beach and the wide expanse of Lyme Bay. -

On Religious Toleration: Prudence and Charity in Augustine, Aquinas

ON RELIGIOUS TOLERATION: PRUDENCE AND CHARITY IN AUGUSTINE, AQUINAS, AND TOCQUEVILLE By MARY C. IMPARATO A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Political Science Written under the direction of P. Dennis Bathory And approved by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION On Religious Toleration: Prudence and Charity in Augustine, Aquinas, and Tocqueville By MARY C. IMPARATO Dissertation Director: P. Dennis Bathory This work seeks to explore the concept of religious toleration as it has been conceived by key thinkers at important junctures in the history of the West in the hopes of identifying some of the animating principles at work in societies confronted with religious difference and dissent. One can observe that, at a time when the political influence of the Catholic Church was ascendant and then in an era of Church hegemony, St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas respectively, faced with religious dissent, argue for toleration in some cases and coercion in others. While, from a contemporary liberal standpoint, one may be tempted to judge their positions to be opportunistic, harsh, or authoritarian, if we read them in the context of their social realities and operative values, we can better understand their stances as emanating ultimately from prudence (that virtue integrating truth and practice) and charity (the love of God and neighbor). With the shattering of Christian unity and the decoupling of throne and altar that occurs in the early modern period, the context for religious toleration is radically altered. -

A Short Essay About Preston Written by Desiree Le

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasd fghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx cvbnmqwertyuPrestoniopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopThea sdevelopmentdfghjk ofl za cityxc throughoutvbnm qwertyui the centuries opasdfghjklzxcvDesireeb nLe Clairem qSG E/1wertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwEnglischer beit Frauyu Kaphegyiiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz Inhaltsverzeichnis: General Information S. 3 Pre-industrial era “ How the city changed during the S. 4 industrialization Developments in the 20th century S. 5 The city today S. 6 Pictures S. 7 Eigenständigkeitserklärung S. 10 Literatur- und Quellenverzeichnis S. 11 Anhang S. 12 2 Preston The development of a city throughout the centuries 1. General information Preston is a city in the shire county of Lancashire, in the North West of England in the sovereign state of the United Kingdom. It’s “located on the north bank of the River Ribble.” (picture 1) 114,300 people live there (ONS, June 2008).1 With 142.22km² it’s about 65km² smaller than Stuttgart. 2 “… The name Preston is derived from Old English words meaning “Priest settlement” and in the Domesday Book appears as Prestune.” 3 The Domesday Book was completed in 1086 and it’s a collection of the great survey of England and Wales. 4 2. Pre-industrial era (shortly before the IR) The plague in November 1631 killed 1100 people in Preston in 12 month. The civil war from 1630 to 1650 and the Battle of Preston in 1648 have been very bad for the town, too. 5 The Jacobite Battle in November 1715 describes the battle, when the troops of King George defeated a Jacobite Army of 2,000 soldiers in the Church Street of Preston. -

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Prestonpans Designation

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Prestonpans The Inventory of Historic Battlefields is a list of nationally important battlefields in Scotland. A battlefield is of national importance if it makes a contribution to the understanding of the archaeology and history of the nation as a whole, or has the potential to do so, or holds a particularly significant place in the national consciousness. For a battlefield to be included in the Inventory, it must be considered to be of national importance either for its association with key historical events or figures; or for the physical remains and/or archaeological potential it contains; or for its landscape context. In addition, it must be possible to define the site on a modern map with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The aim of the Inventory is to raise awareness of the significance of these nationally important battlefield sites and to assist in their protection and management for the future. Inventory battlefields are a material consideration in the planning process. The Inventory is also a major resource for enhancing the understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of historic battlefields, for promoting education and stimulating further research, and for developing their potential as attractions for visitors. Designation Record and Full Report Contents Name - Context Alternative Name(s) Battlefield Landscape Date of Battle - Location Local Authority - Terrain NGR Centred - Condition Date of Addition to Inventory Archaeological and Physical Date of Last Update Remains and Potential -

Jacobite Gleanings from the State Manuscripts

JACOBITE GLEANINGS FROM STATE MANUSCRIPTS Short Sketches of Jacobites The Transportations in 1745 BY J. MACBETH FORBES OLIPHANT ANDERSON AND FERRIER SAINT MARY STREET, EDINBURGH, AND 21 PATERNOSTER SQUARE, LONDON 1903 SHORT SKETCHES OF JACOBITES Contents SHORT SKETCHES OF JACOBITES ................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I .................................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II THE PRISONERS Landed Proprietors—Students. ............................. 10 CHAPTER III THE PRISONERS The Battle of Prestonpans—Some minor Combatants...................................................................................................................... 14 CHAPTER IV THE PRISONERS Trading Class—Working Class— Professional Class— The Walkinshaws. ......................................................................... 19 CHAPTER V The Epic of the „45—Prince Gustavus Vasa, the Swedish Pretender. ........................................................................................................................ 24 THE TRANSPORTATIONS IN 1745 ................................................................... 27 CHAPTER I Stamping out the Rebellion—Life on board the prison-ships— Suggested cure for sickness at Tilbury Fort. .................................................................. 27 CHAPTER II Drawing lots—Acts as to transportation—Abolition of Heritable Jurisdictions disarming, etc., of Highlanders—Escapes in 1716—Offers to transport -

Let's Cycle Preston and South Ribble

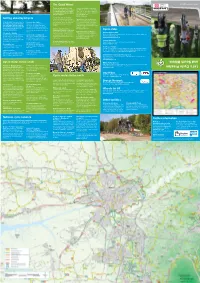

The Guild Wheel www.lancashire.gov.uk The Preston Guild Wheel is a 21 mile Stop at the floating Visitor Village where circular cycle route round Preston opened you will find a cafe, shops and information comms: xxxx to celebrate 2012 Guild. Preston Guild centre. There are lakes, hides, walking trails occurs every 20 years and has a history and a play area. The reserve is owned by going back 700 years. Lancashire Wildlife Trust. www.brockholes.org The Guild Wheel links the city with the Getting about by bicycle surrounding countryside and river corridor. Preston Docks – Stop for a drink at one It takes you through the different landscapes of the cafes and pubs by the dockside or Did you know that there are now over 75 Cycle to the station that surround the city, including riverside ride down to the lock gates. When opened km of traffic free cycle paths in Preston Fed up with motorway driving. More and meadows, historic parks and ancient in 1892 it was the largest dock basin in and South Ribble? With new routes like more people are cycling to the station woodland. Europe employing over 500 people. Today the Guild Wheel and 20 mph speed limits and catching the train. A new cycle hub is the dock is a marina. it is becoming more attractive to get opening at Preston station in Summer 2016. Attractions along the route include: www.prestondock.co.uk around the area by bicycle. There is good cycle parking at other stations Avenham and Miller Parks – Ride through Cycle clubs in the area. -

John Hodgson Soldier, Surgeon, Agitator and Quaker?

220 JOHN HODGSON SOLDIER, SURGEON, AGITATOR AND QUAKER? n 1954 Alan Cole presented "More Light on John Hodgson" in relation to the Peace Testimony of 1659 and two Quaker tracts of Ithat year, "A Letter from a Member of the Army, to the Committee of Safety, and Councell of Officers of the Army" and "Love, Kindness, and due Respect".1 Cole's piece was, in part, a response to an earlier consideration of the two tracts and their authorship.2 Unlike the 1950 piece Cole convincingly argued that the John Hodgson who signed both tracts was the same man. "It would certainly be a rather striking coincidence if two writers of the same name had published tracts with such marked similarities of argument and style as we find in these two pamphlets...".3 The other key point in Cole's article was that John Hodgson the Quaker, the author of both tracts, was "a civilian in the summer of 1659 when he addressed his paper, 'Love, Kindness, and due Respect' to the restored Rump... and that he subsequently enlisted or re-enlisted in the Army".4 Although Cole was unable to detail who Hodgson the Quaker might have been the 1950 piece very briefly dismissed a Captain John Hodgson as a possible author of the two tracts.5 However a more detailed consideration of this Captain John Hodgson does suggest that he may be the author of these tracts. There are some interesting parallels between what is known of John Hodgson the Quaker author and this Captain John Hodgson, soldier.6 Captain John Hodgson entered a company of foot in Sir Thomas Fairfax's regiment in his native Yorkshire in late 1642.