John Hodgson Soldier, Surgeon, Agitator and Quaker?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winckley Square Around Here’ the Geography Is Key to the History Walton

Replica of the ceremonial Roman cavalry helmet (c100 A.D.) The last battle fought on English soil was the battle of Preston in unchallenged across the bridge and began to surround Preston discovered at Ribchester in 1796: photo Steve Harrison 1715. Jacobites (the word comes from the Latin for James- town centre. The battle that followed resulted in far more Jacobus) were the supporters of James, the Old Pretender; son Government deaths than of Jacobites but led ultimately to the of the deposed James II. They wanted to see the Stuart line surrender of the supporters of James. It was recorded at the time ‘Not much history restored in place of the Protestant George I. that the Jacobite Gentlemen Ocers, having declared James the King in Preston Market Square, spent the next few days The Jacobites occupied Preston in November 1715. Meanwhile celebrating and drinking; enchanted by the beauty of the the Government forces marched from the south and east to women of Preston. Having married a beautiful woman I met in a By Steve Harrison: Preston. The Jacobites made no attempt to block the bridge at Preston pub, not far from the same market square, I know the Friend of Winckley Square around here’ The Geography is key to the History Walton. The Government forces of George I marched feeling. The Ribble Valley acts both as a route and as a barrier. St What is apparent to the Friends of Winckley Square (FoWS) is that every aspect of the Leonard’s is built on top of the millstone grit hill which stands between the Rivers Ribble and Darwen. -

Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper

Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper Notes Contents 1 Visiting the Exhibition 2 The Exhibition 3 Answers to the Trail Page 1 – Family Tree Page 2 – 1689 (James VII and II) Page 3 – 1708 (James VIII and III) Page 4 – 1745 (Bonnie Prince Charlie) 4 After your visit 5 Additional Resources National Museums Scotland Scottish Charity, No. SC011130 illustrations © Jenny Proudfoot www.jennyproudfoot.co.uk Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper Notes 1 Introduction Explore the real story of Prince Charles Edward Stuart, better known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, and the rise and fall of the Jacobites. Step into the world of the Royal House of Stuart, one dynasty divided into two courts by religion, politics and war, each fighting for the throne of thethree kingdoms of Scotland, England and Ireland. Discover how four Jacobite kings became pawns in a much wider European political game. And follow the Jacobites’ fight to regain their lost kingdoms through five challenges to the throne, the last ending in crushing defeat at the Battle of Culloden and Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape to the Isle of Skye and onwards to Europe. The schools trail will help your class explore the exhibition and the Jacobite story through three key players: James VII and II, James VIII and III and Bonnie Prince Charlie. 1. Visiting the Exhibition (Please share this information with your adult helpers) Page Character Year Exhibition sections Important information 1 N/A N/A The Stuart Dynasty and the Union of the Crowns • Food and drink is not permitted 2 James VII 1688 Dynasty restored, Dynasty • Photography is not allowed and II divided, A court in exile • When completing the trail, ensure pupils use a pencil 3 James VIII 1708- The challenges of James VIII and III 1715 and III, All roads lead to Rome • You will enter and exit via different doors. -

Insert Document Title What's New in England 2015 and Beyond for The

Insert Document Title Here What’s New in England 2015 and Beyond For the most up to date guide, please check: http://www.visitengland.org/media/resources/whats_new.aspx 1. Accommodation Bouja by Hoseasons, Devon and Hampshire From 30 January Hoseasons will be introducing ‘affordable luxury breaks’ under new brand Bouja. Set across six countryside and coastal locations, Bouja will offer holiday homes with a deck, patio or private garden, as well as amenities including a flat-screen TV. Bike hire, nature trails and great quality bistros and restaurants will be offered nearby, while quirkier spaces will be provided by the designer Bouja Boutique. Beach Cove Coastal Retreat will be the first location to open, with others following throughout Q1. http://www.hoseasons.co.uk/ The Hospital Club, London January The former hospital turned ‘creative hub’, The Hospital Club, has now added 15 hotel rooms to its Covent Garden venue. The rooms boast sumptuous interiors and stained glass by Russell Sage studios, providing guests with a home away from home. Suites also include a private terrace, rainforest showers and lounge area. Rooms start from £180 per night. http://www.thehospitalclub.com The 25 Boutique, Torquay January A luxury 5 star boutique B&B, is located a 10 minute walk from the centre of Torquay and close by to the Riviera International Centre and Torre abbey. Each room is individually designed and provides different sizes and amenities. http://www.the25.uk/ The Seaside Boarding House, Restaurant & Bar, Burton Bradstock February/March The Seaside Boarding House Restaurant and Bar is set on the cliffs overlooking the sweep of Dorset’s famous Chesil Beach and the wide expanse of Lyme Bay. -

A Short Essay About Preston Written by Desiree Le

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasd fghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx cvbnmqwertyuPrestoniopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopThea sdevelopmentdfghjk ofl za cityxc throughoutvbnm qwertyui the centuries opasdfghjklzxcvDesireeb nLe Clairem qSG E/1wertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwEnglischer beit Frauyu Kaphegyiiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz Inhaltsverzeichnis: General Information S. 3 Pre-industrial era “ How the city changed during the S. 4 industrialization Developments in the 20th century S. 5 The city today S. 6 Pictures S. 7 Eigenständigkeitserklärung S. 10 Literatur- und Quellenverzeichnis S. 11 Anhang S. 12 2 Preston The development of a city throughout the centuries 1. General information Preston is a city in the shire county of Lancashire, in the North West of England in the sovereign state of the United Kingdom. It’s “located on the north bank of the River Ribble.” (picture 1) 114,300 people live there (ONS, June 2008).1 With 142.22km² it’s about 65km² smaller than Stuttgart. 2 “… The name Preston is derived from Old English words meaning “Priest settlement” and in the Domesday Book appears as Prestune.” 3 The Domesday Book was completed in 1086 and it’s a collection of the great survey of England and Wales. 4 2. Pre-industrial era (shortly before the IR) The plague in November 1631 killed 1100 people in Preston in 12 month. The civil war from 1630 to 1650 and the Battle of Preston in 1648 have been very bad for the town, too. 5 The Jacobite Battle in November 1715 describes the battle, when the troops of King George defeated a Jacobite Army of 2,000 soldiers in the Church Street of Preston. -

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Prestonpans Designation

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Prestonpans The Inventory of Historic Battlefields is a list of nationally important battlefields in Scotland. A battlefield is of national importance if it makes a contribution to the understanding of the archaeology and history of the nation as a whole, or has the potential to do so, or holds a particularly significant place in the national consciousness. For a battlefield to be included in the Inventory, it must be considered to be of national importance either for its association with key historical events or figures; or for the physical remains and/or archaeological potential it contains; or for its landscape context. In addition, it must be possible to define the site on a modern map with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The aim of the Inventory is to raise awareness of the significance of these nationally important battlefield sites and to assist in their protection and management for the future. Inventory battlefields are a material consideration in the planning process. The Inventory is also a major resource for enhancing the understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of historic battlefields, for promoting education and stimulating further research, and for developing their potential as attractions for visitors. Designation Record and Full Report Contents Name - Context Alternative Name(s) Battlefield Landscape Date of Battle - Location Local Authority - Terrain NGR Centred - Condition Date of Addition to Inventory Archaeological and Physical Date of Last Update Remains and Potential -

Jacobite Gleanings from the State Manuscripts

JACOBITE GLEANINGS FROM STATE MANUSCRIPTS Short Sketches of Jacobites The Transportations in 1745 BY J. MACBETH FORBES OLIPHANT ANDERSON AND FERRIER SAINT MARY STREET, EDINBURGH, AND 21 PATERNOSTER SQUARE, LONDON 1903 SHORT SKETCHES OF JACOBITES Contents SHORT SKETCHES OF JACOBITES ................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I .................................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II THE PRISONERS Landed Proprietors—Students. ............................. 10 CHAPTER III THE PRISONERS The Battle of Prestonpans—Some minor Combatants...................................................................................................................... 14 CHAPTER IV THE PRISONERS Trading Class—Working Class— Professional Class— The Walkinshaws. ......................................................................... 19 CHAPTER V The Epic of the „45—Prince Gustavus Vasa, the Swedish Pretender. ........................................................................................................................ 24 THE TRANSPORTATIONS IN 1745 ................................................................... 27 CHAPTER I Stamping out the Rebellion—Life on board the prison-ships— Suggested cure for sickness at Tilbury Fort. .................................................................. 27 CHAPTER II Drawing lots—Acts as to transportation—Abolition of Heritable Jurisdictions disarming, etc., of Highlanders—Escapes in 1716—Offers to transport -

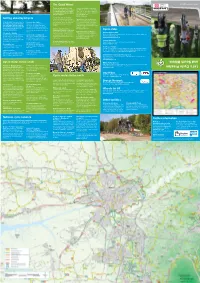

Let's Cycle Preston and South Ribble

The Guild Wheel www.lancashire.gov.uk The Preston Guild Wheel is a 21 mile Stop at the floating Visitor Village where circular cycle route round Preston opened you will find a cafe, shops and information comms: xxxx to celebrate 2012 Guild. Preston Guild centre. There are lakes, hides, walking trails occurs every 20 years and has a history and a play area. The reserve is owned by going back 700 years. Lancashire Wildlife Trust. www.brockholes.org The Guild Wheel links the city with the Getting about by bicycle surrounding countryside and river corridor. Preston Docks – Stop for a drink at one It takes you through the different landscapes of the cafes and pubs by the dockside or Did you know that there are now over 75 Cycle to the station that surround the city, including riverside ride down to the lock gates. When opened km of traffic free cycle paths in Preston Fed up with motorway driving. More and meadows, historic parks and ancient in 1892 it was the largest dock basin in and South Ribble? With new routes like more people are cycling to the station woodland. Europe employing over 500 people. Today the Guild Wheel and 20 mph speed limits and catching the train. A new cycle hub is the dock is a marina. it is becoming more attractive to get opening at Preston station in Summer 2016. Attractions along the route include: www.prestondock.co.uk around the area by bicycle. There is good cycle parking at other stations Avenham and Miller Parks – Ride through Cycle clubs in the area. -

The Colonial Clergy of the Middle Colonies New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania 1628-1776

The Colonial Clergy of the Middle Colonies New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania 1628-1776 BY FREDERICK LEWIS WEIS EDITOR'S NOTE NE of the most useful tools in the chest of the bibliog- O rapher, historian, and librarian is the series of little volumes by Dr. Weis on the colonial clergy. The gap in this series, the volume on the clergy of the Middle Colonies, was proving such a great hindrance to our revision of Evans' American Bibliography, that we have decided to print this volume for our own use, and to publish it in order to share it with others. The first volume of this series. The Colonial Clergy and the Colonial Churches of New England (Lancaster, 1936), is out of print. The Colonial Clergy of Maryland, Delaware, and Georgia (Lancaster, 1950), and The Colonial Clergy of Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina (Boston, 1955) may be obtained of the author (at Dublin, New Hampshire) for $3 a volume. The institutional data which is provided at the end of the New England volume is for the other colonies issued in a separate volume. The Colonial Churches and the Colonial Clergy in the Middle and Southern Colonies (Lancaster, 1938), which is still available from the author. The biographical data on the clergy of the Middle Colonies here printed is also available in monograph form from the American Antiquarian Society. C. K. S. i68 AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [Oct., BENJAMIN ABBOTT, b. Long Island, N.Y., 1732; member of the Philadelphia Conference of Methodists, 1773-1789; preached at Penns- neck, N. -

Cromwell Study Day: October 2014 66

CROMWELL STUDY DAY: OCTOBER 2014 ‘…LOOKED ON AS A WONDER, THAT NEVER BEHELD HIS ENEMIES IN THE FACE BUT RETURNED FROM THEM CROWNED ALWAYS WITH RENOWN AND HONOUR…’: CROMWELL’S CONTRIBUTION TO PARLIAMENT’S MILITARY VICTORIES, 1642–51.1 By Prof Peter Gaunt Mercurius Civicus, London’s Intelligencer of Truth Impartially Related from Thence to the Whole Kingdom, in its edition for the week 23–30 April 1646, by which time full parliamentarian victory in the main civil war was in sight, gushingly reported as its lead news item that: The active, pious and gallant commander, Lieutenant General Cromwell, being come to the city of London, not for any ease or pleasure, but with the more speed to advance the great cause in hand for the reformation of religion and the resettling the peace and government of the kingdom, he on this day, April 23rd, repaired to the parliament. As he passed through the hall at Westminster he was looked on as a wonder, that never beheld his enemies in the face but returned from them crowned always with renown and honour, nor ever brought his colours from the field but he did wind up victory within them. Having taken his place in the House of Commons, Mr Speaker by order of the whole House gave him great thanks for the unwearied services undertaken by him for the honour and safety of the parliament and the welfare of the kingdom. Samuel Pecke’s A Perfect Diurnall of Some Passages in Parliament of 20–27 April reported the same incident in similarly flowery tones, noting the return to London and to the Commons of ‘the ever renowned and never to be forgotten Lieutenant-General Cromwell’, upon whose arrival in the chamber his fellow MPs gave way to ‘much rejoicing at his presence and welfare’ and to giving ‘testimony of their true respects to his extraordinary services for the kingdom’. -

The Castlecary Hoard and the Civil War Currency Of

THE CASTLECARY HOARD AND THE CIVIL WAR CURRENCY OF SCOTLAND DONAL BATESON THIS publication of an unrecorded hoard from Castlecary, ending with coins of the 1640s, presents an opportunity to examine the Civil War coin hoards from Scotland and the Scottish currency of the period. The hoard This is an enigmatic hoard in so far as it was recently re-discovered, in the National Museums of Scotland merely with a note saying, 'Castlecary Hoard 1926'. Nothing more is known of the circumstances of its finding or indeed whether it was brought to the then National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland in 1926 or subsequently. In any event it appears to have been put to one side and not returned to.1 Castlecary is a small village in Stirlingshire situated to the west of Falkirk.2 The find contains 134 coins, all of silver. The majority are English, issues of the Tower Mint, of Elizabeth I, James I and Charles I. In addition there are three Scottish coins of James VI as well as four of his Irish shillings. It includes no foreign coin. A summary shows: 8 shillings and 36 sixpences of Elizabeth I (1558-1603) 1 half-crown, 10 shillings and 8 sixpences of James I (1603-25) 26 half-crowns, 31 shillings and 7 sixpences of Charles I (1625-49) 2 thistle merks and 1 thirty shillings (Scots) of James VI (1567-1625) 4 Irish shillings of James I The face value of the English, and Irish, coins in the mid-seventeenth century was £7 6 s Od. -

Treatment of Prisoners of War in England During the English Civil Wars, 22 August, 1642 - 30 January, 1648/49

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1968 Treatment of prisoners of war in England during the English Civil Wars, 22 August, 1642 - 30 January, 1648/49 Gary Tristram Cummins The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cummins, Gary Tristram, "Treatment of prisoners of war in England during the English Civil Wars, 22 August, 1642 - 30 January, 1648/49" (1968). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3948. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3948 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRBATJ^MT OF PRISONERS OF WAR IN EM6LAND 0URIM6 THE ENGLISH CIVIL WARS 22 AUGUST 1642 - 30 JANUARY 1648/49 by ISARY TRISTRAM C»#IIN8 i.A, University oi Mmtam, 1964 Presented In partial fulftll»©nt of th« requirements for the d®gr®e of Master of Arts University of Montana 19fi8 Approved: .^.4.,.3dAAsdag!Ac. '»€&iat« December 12, 1968 Dste UMI Number EP34264 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

PRESTON TITHEBARN REGENERATION, PRESTON, Lancashire

PRESTON TITHEBARN REGENERATION, PRESTON, Lancashire Archaeological desk-based assessment Oxford Archaeology North November 2007 Ramboll Whitybird, on behalf of the Preston Tithebarn Partnership NGR (centred): SD 541 294 OA North Ref No: L9902 Preston Tithebarn Regeneration Area, Preston, Lancashire: Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................5 1. INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................7 1.1 Circumstances of Project.....................................................................................7 2. METHODOLOGY .........................................................................................................9 2.1 Project Design.....................................................................................................9 2.2 Legislative Framework........................................................................................9 2.3 Planning Policy Context....................................................................................10 2.4 Desk-Based Assessment....................................................................................12 2.5 Walkover Survey...............................................................................................13 2.6 Assessment Methodology