“Essential Agony”: the Battle of Dunbar 1650 by Arran Johnston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winckley Square Around Here’ the Geography Is Key to the History Walton

Replica of the ceremonial Roman cavalry helmet (c100 A.D.) The last battle fought on English soil was the battle of Preston in unchallenged across the bridge and began to surround Preston discovered at Ribchester in 1796: photo Steve Harrison 1715. Jacobites (the word comes from the Latin for James- town centre. The battle that followed resulted in far more Jacobus) were the supporters of James, the Old Pretender; son Government deaths than of Jacobites but led ultimately to the of the deposed James II. They wanted to see the Stuart line surrender of the supporters of James. It was recorded at the time ‘Not much history restored in place of the Protestant George I. that the Jacobite Gentlemen Ocers, having declared James the King in Preston Market Square, spent the next few days The Jacobites occupied Preston in November 1715. Meanwhile celebrating and drinking; enchanted by the beauty of the the Government forces marched from the south and east to women of Preston. Having married a beautiful woman I met in a By Steve Harrison: Preston. The Jacobites made no attempt to block the bridge at Preston pub, not far from the same market square, I know the Friend of Winckley Square around here’ The Geography is key to the History Walton. The Government forces of George I marched feeling. The Ribble Valley acts both as a route and as a barrier. St What is apparent to the Friends of Winckley Square (FoWS) is that every aspect of the Leonard’s is built on top of the millstone grit hill which stands between the Rivers Ribble and Darwen. -

Earl of Dunbar and the Founder of HDT WHAT? INDEX

HENRY’S RELATIVES SUB SPE MISS ANNA JANE DUNBAR ASA DUNBAR CHARLES DUNBAR COUSIN CHARLES DUNBAR CYNTHIA DUNBAR THOREAU LOUISA DUNBAR MARY JONES DUNBAR ELIJAH DUNBAR Henry David Thoreau’s great-great-great-grandfather Robert Dunbar was born about 1630-1634 presumably in Scotland, and shortly after 1650 emigrated to Hingham in the Plymouth Colony where he and Rose Dunbar, Thoreau’s great-great-great-grandmother, raised three daughters and eight sons. Robert died on September 19, 1693 and Rose died in November 1700, there in Hingham. Another member of the extended clan and thus a relative of Henry David Thoreau, William Dunbar (1460?-1520?), is considered to have been one of the finest poets produced by Scotland. However, closer to Thoreau genealogically was the Reverend Samuel Dunbar (1704- 1783) of Stoughton MA, whose sermons are preserved by the American Antiquarian Society. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE DUNBAR CLAN THE DUNBARS ANNO DOMINI 835 After the Battle of Scone in which Dursken was slain and his Picts dispersed, King Kenneth I of Scotland awarded a Pict wood-and-wattle strongpoint overlooking the River Forth and the south shore of the entrance to the North Sea inlet known as the Firth of Forth that had been seized and burned by Kenneth Macalpin to a Scots captain named Bar.1 This strongpoint would become known in Gaelic as Dun Bar, or “the tower or fortress of Bar on the hill.” The first person to employ Dunbar as a family name was the Gospatric I who would during the 12th Century rebuild this fortification as a stone castle. -

Now the War Is Over

Pollard, T. and Banks, I. (2010) Now the wars are over: The past, present and future of Scottish battlefields. International Journal of Historical Archaeology,14 (3). pp. 414-441. ISSN 1092-7697. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/45069/ Deposited on: 17 November 2010 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Now the Wars are Over: the past, present and future of Scottish battlefields Tony Pollard and Iain Banks1 Suggested running head: The past, present and future of Scottish battlefields Centre for Battlefield Archaeology University of Glasgow The Gregory Building Lilybank Gardens Glasgow G12 8QQ United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)141 330 5541 Fax: +44 (0)141 330 3863 Email: [email protected] 1 Centre for Battlefield Archaeology, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland 1 Abstract Battlefield archaeology has provided a new way of appreciating historic battlefields. This paper provides a summary of the long history of warfare and conflict in Scotland which has given rise to a large number of battlefield sites. Recent moves to highlight the archaeological importance of these sites, in the form of Historic Scotland’s Battlefields Inventory are discussed, along with some of the problems associated with the preservation and management of these important cultural sites. 2 Keywords Battlefields; Conflict Archaeology; Management 3 Introduction Battlefield archaeology is a relatively recent development within the field of historical archaeology, which, in the UK at least, has itself not long been established within the archaeological mainstream. Within the present context it is noteworthy that Scotland has played an important role in this process, with the first international conference devoted to battlefield archaeology taking place at the University of Glasgow in 2000 (Freeman and Pollard, 2001). -

Johnston of Warriston

F a m o u s Sc o t s S e r i e s Th e following Volum es are now ready M S ARLYLE H ECT O R . M C HERSO . T HO A C . By C A P N LL N R M Y O L H T SM E T O . A A A SA . By IP AN A N H U GH MI R E T H LE SK . LLE . By W. K I A H K ! T LOR INN Es. JO N NO . By A . AY R ERT U RNS G BR EL SET OUN. OB B . By A I L D O H GE E. T H E BA L A I ST S. By J N DDI RD MER N Pro fe sso H ER KLESS. RICH A CA O . By r SIR MES Y SI MPSON . EV E L T R E S M SO . JA . By B AN Y I P N M R P o fesso . G R E BLA I KIE. T HOMAS CH AL E S. By r r W A D N MES S ELL . E T H LE SK. JA BO W . By W K I A I M L E OL H T SME T O . T OB AS S O L T T . By IP AN A N U G . T O MON D . FLET CHER O F SA LT O N . By . W . R U P Sir GEOR E DO L S. T HE BLACKWOOD G O . By G UG A RM M LEOD OH ELL OO . -

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Dunbar II Designation

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Dunbar II The Inventory of Historic Battlefields is a list of nationally important battlefields in Scotland. A battlefield is of national importance if it makes a contribution to the understanding of the archaeology and history of the nation as a whole, or has the potential to do so, or holds a particularly significant place in the national consciousness. For a battlefield to be included in the Inventory, it must be considered to be of national importance either for its association with key historical events or figures; or for the physical remains and/or archaeological potential it contains; or for its landscape context. In addition, it must be possible to define the site on a modern map with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The aim of the Inventory is to raise awareness of the significance of these nationally important battlefield sites and to assist in their protection and management for the future. Inventory battlefields are a material consideration in the planning process. The Inventory is also a major resource for enhancing the understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of historic battlefields, for promoting education and stimulating further research, and for developing their potential as attractions for visitors. Designation Record Contents Name Date of Addition to Inventory Alternative Name(s) Date of Last Update Date of Battle Overview and Statement of Local Authority Significance NGR Centred Inventory Boundary Inventory of Historic Battlefields DUNBAR II Alternative Names: None 3 September 1650 Local Authority: East Lothian NGR centred: NT 690 767 Date of Addition to Inventory: 21 March 2011 Date of last update: 14 December 2012 Overview and Statement of Significance The battle of Dunbar is significant as the most influential battle fought in Scotland during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. -

A Short Essay About Preston Written by Desiree Le

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasd fghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx cvbnmqwertyuPrestoniopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopThea sdevelopmentdfghjk ofl za cityxc throughoutvbnm qwertyui the centuries opasdfghjklzxcvDesireeb nLe Clairem qSG E/1wertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwEnglischer beit Frauyu Kaphegyiiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz Inhaltsverzeichnis: General Information S. 3 Pre-industrial era “ How the city changed during the S. 4 industrialization Developments in the 20th century S. 5 The city today S. 6 Pictures S. 7 Eigenständigkeitserklärung S. 10 Literatur- und Quellenverzeichnis S. 11 Anhang S. 12 2 Preston The development of a city throughout the centuries 1. General information Preston is a city in the shire county of Lancashire, in the North West of England in the sovereign state of the United Kingdom. It’s “located on the north bank of the River Ribble.” (picture 1) 114,300 people live there (ONS, June 2008).1 With 142.22km² it’s about 65km² smaller than Stuttgart. 2 “… The name Preston is derived from Old English words meaning “Priest settlement” and in the Domesday Book appears as Prestune.” 3 The Domesday Book was completed in 1086 and it’s a collection of the great survey of England and Wales. 4 2. Pre-industrial era (shortly before the IR) The plague in November 1631 killed 1100 people in Preston in 12 month. The civil war from 1630 to 1650 and the Battle of Preston in 1648 have been very bad for the town, too. 5 The Jacobite Battle in November 1715 describes the battle, when the troops of King George defeated a Jacobite Army of 2,000 soldiers in the Church Street of Preston. -

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Prestonpans Designation

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Prestonpans The Inventory of Historic Battlefields is a list of nationally important battlefields in Scotland. A battlefield is of national importance if it makes a contribution to the understanding of the archaeology and history of the nation as a whole, or has the potential to do so, or holds a particularly significant place in the national consciousness. For a battlefield to be included in the Inventory, it must be considered to be of national importance either for its association with key historical events or figures; or for the physical remains and/or archaeological potential it contains; or for its landscape context. In addition, it must be possible to define the site on a modern map with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The aim of the Inventory is to raise awareness of the significance of these nationally important battlefield sites and to assist in their protection and management for the future. Inventory battlefields are a material consideration in the planning process. The Inventory is also a major resource for enhancing the understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of historic battlefields, for promoting education and stimulating further research, and for developing their potential as attractions for visitors. Designation Record and Full Report Contents Name - Context Alternative Name(s) Battlefield Landscape Date of Battle - Location Local Authority - Terrain NGR Centred - Condition Date of Addition to Inventory Archaeological and Physical Date of Last Update Remains and Potential -

Locality and Allegiance: English Lothian, 1296-1318

University of Huddersfield Repository Gledhill, Jonathan Locality and Allegiance: English Lothian, 1296-1318 Original Citation Gledhill, Jonathan (2012) Locality and Allegiance: English Lothian, 1296-1318. In: England and Scotland at War, c.1296-c.1513. Brill, Leiden, pp. 157-182. ISBN 9789004229822 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/14669/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ 7 Locality and Allegiance: English Lothian, 1296-1318 JONATHAN D. GLEDHILL The enforced abdication of King John in July 1296 and the consequent degrading of Scotland from an independent kingdom to a mere land of the English monarchy introduced a difficult political dualism into Scottish politics. The military conquest of Scotland meant that its barons and knights now had to decide whether to accept English claims to overlordship that were directly exercised through a colonial government, or continue to support a series of guardians who acted in King John’s name: a situation that lasted until the negotiated surrender of the guardian John Comyn of Badenoch at Strathord in 1304. -

Declaration of Arbroath Sealants' Information Sheets

Alexander Fraser Alexander Fraser was born into the Touch-Fraser line of the family but his exact date of birth is unknown. In autumn 1307, Alexander Fraser swore fealty to Robert the Bruce and accompanied the king on military campaigns in 1307-08. He fought at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. He may have been knighted before the Battle of Bannockburn and the title seems to have first been used in 1315, when Robert Bruce gave lands to his ‘beloved and faithful’ Alexander Fraser, knight. In about 1316 Alexander Fraser married Mary Bruce, sister of Robert the Bruce. He had become chamberlain of Scotland, the title being used in a charter dated 10 December 1319. He held this position until at least 5 March 1327. At the parliament of 1320, he attached his seal to the Declaration of Arbroath. His other titles included sheriff of Kincardine and sheriff of Stirling, and he held extensive lands north of the Firth of Forth. Alexander Fraser’s extensive estates and alliance to the royal family must have made him an influential figure. He fought and died at the Battle of Dupplin on 10-11 August 1332. Definitions: Fealty = promise to be loyal Chamberlain = manager of a royal household Charter = a legal document that sets out rights or obligations Image: Mike Brooks © Queen’s Printer for Scotland, NRS, SP13/7 January 2021 William Oliphant Sir William Oliphant of Dupplin and Aberdalgie, attached his seal to the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320. The earliest reference to him is in a list of prisoners captured at the Battle of Dunbar in 1296. -

Jacobite Gleanings from the State Manuscripts

JACOBITE GLEANINGS FROM STATE MANUSCRIPTS Short Sketches of Jacobites The Transportations in 1745 BY J. MACBETH FORBES OLIPHANT ANDERSON AND FERRIER SAINT MARY STREET, EDINBURGH, AND 21 PATERNOSTER SQUARE, LONDON 1903 SHORT SKETCHES OF JACOBITES Contents SHORT SKETCHES OF JACOBITES ................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I .................................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II THE PRISONERS Landed Proprietors—Students. ............................. 10 CHAPTER III THE PRISONERS The Battle of Prestonpans—Some minor Combatants...................................................................................................................... 14 CHAPTER IV THE PRISONERS Trading Class—Working Class— Professional Class— The Walkinshaws. ......................................................................... 19 CHAPTER V The Epic of the „45—Prince Gustavus Vasa, the Swedish Pretender. ........................................................................................................................ 24 THE TRANSPORTATIONS IN 1745 ................................................................... 27 CHAPTER I Stamping out the Rebellion—Life on board the prison-ships— Suggested cure for sickness at Tilbury Fort. .................................................................. 27 CHAPTER II Drawing lots—Acts as to transportation—Abolition of Heritable Jurisdictions disarming, etc., of Highlanders—Escapes in 1716—Offers to transport -

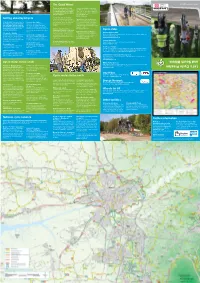

Let's Cycle Preston and South Ribble

The Guild Wheel www.lancashire.gov.uk The Preston Guild Wheel is a 21 mile Stop at the floating Visitor Village where circular cycle route round Preston opened you will find a cafe, shops and information comms: xxxx to celebrate 2012 Guild. Preston Guild centre. There are lakes, hides, walking trails occurs every 20 years and has a history and a play area. The reserve is owned by going back 700 years. Lancashire Wildlife Trust. www.brockholes.org The Guild Wheel links the city with the Getting about by bicycle surrounding countryside and river corridor. Preston Docks – Stop for a drink at one It takes you through the different landscapes of the cafes and pubs by the dockside or Did you know that there are now over 75 Cycle to the station that surround the city, including riverside ride down to the lock gates. When opened km of traffic free cycle paths in Preston Fed up with motorway driving. More and meadows, historic parks and ancient in 1892 it was the largest dock basin in and South Ribble? With new routes like more people are cycling to the station woodland. Europe employing over 500 people. Today the Guild Wheel and 20 mph speed limits and catching the train. A new cycle hub is the dock is a marina. it is becoming more attractive to get opening at Preston station in Summer 2016. Attractions along the route include: www.prestondock.co.uk around the area by bicycle. There is good cycle parking at other stations Avenham and Miller Parks – Ride through Cycle clubs in the area. -

Gazetteer of Selected Scottish Battlefields

Scotland’s Historic Fields of Conflict Gazetteer: page 1 GAZETTEER OF SELECTED SCOTTISH BATTLEFIELDS LIST OF CONTENTS ABERDEEN II ............................................................................................................. 4 ALFORD ...................................................................................................................... 9 ANCRUM MOOR...................................................................................................... 19 AULDEARN .............................................................................................................. 26 BANNOCKBURN ..................................................................................................... 34 BOTHWELL BRIDGE .............................................................................................. 59 BRUNANBURH ........................................................................................................ 64 DRUMCLOG ............................................................................................................. 66 DUNBAR II................................................................................................................ 71 DUPPLIN MOOR ...................................................................................................... 79 FALKIRK I ................................................................................................................ 87 FALKIRK II ..............................................................................................................