Torah from Zion: Gentile Conversion and Law Observance in the Septuagint of Isaiah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Old Greek of Isaiah Septuagint and Cognate Studies

The Old Greek Of IsaIah Septuagint and Cognate Studies Editor Wolfgang Kraus Editorial Board Robert Hiebert Karen H. Jobes Siegfried Kreuzer Arie van der Kooij Volume 61 The Old Greek Of IsaIah The Old Greek Of IsaIah an analysIs Of ITs Pluses and MInuses MIrjaM van der vOrM-CrOuGhs SBL Press Atlanta Copyright © 2014 by SBL Press All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, SBL Press, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329, USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Van der Vorm-Croughs, Mirjam. The old Greek of Isaiah : an analysis of its pluses and minuses / Mirjam van der Vorm-Croughs. pages cm. — (Society of Biblical Literature Septuagint and cognate stud- ies ; no. 61) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58983-978-6 (paper binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-58983- 980-9 (electronic format) — ISBN 978-1-58983-979-3 (hardcover binding : alk. paper) 1. Bible. Isaiah. Greek—Versions—Septuagint. 2. Bible. Isaiah—Language, style. 3. Greek language, Biblical. 4. Hebrew language. I. Title. BS1514.G7S486 2014 224’.10486—dc23 2014010033 Printed on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 CONTENTS Preface ix Abbreviations xi CHAPTER 1. -

The Septuagintal Isaian Use of Nomos in the Lukan Presentation Narrative

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects The eptuaS gintal Isaian Use of Nomos in the Lukan Presentation Narrative Mark Walter Koehne Marquette University Recommended Citation Koehne, Mark Walter, "The eS ptuagintal Isaian Use of Nomos in the Lukan Presentation Narrative" (2010). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 33. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/33 THE SEPTUAGINTAL ISAIAN USE OF ΝΌΜΟΣ IN THE LUKAN PRESENTATION NARRATIVE by Mark Walter Koehne, B.A., M.A. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2010 ABSTRACT THE SEPTUAGINTAL ISAIAN USE OF ΝΌΜΟΣ IN THE LUKAN PRESENTATION NARRATIVE Mark Walter Koehne, B.A., M.A. Marquette University, 2010 Scholars have examined several motifs in Luke 2:22-35, the ”Presentation” of the Gospel of Luke. However, scholarship scarcely has treated the theme of νόμος, the Νόμος is .תורה Septuagintal word Luke uses as a translation of the Hebrew word mentioned four times in the Presentation narrative; it also is a word in Septuagintal Isaiah to which the metaphor of light in Luke 2:32 alludes. In 2:22-32—a pivotal piece within Luke-Acts—νόμος relates to several themes, including ones David Pao discusses in his study on Isaiah’s portrayal of Israel’s restoration, appropriated by Luke. My dissertation investigates, for the first time, the Septuagintal Isaian use of νόμος in this pericope. My thesis is that Luke’s use of νόμος in the Presentation pericope highlight’s Jesus’ identity as the Messiah who will restore and fulfill Israel. -

1 Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos

Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos: Some Tentative Thoughts David Berger The deep and systemic tension between contemporary egalitarianism and many authoritative Jewish texts about gentiles takes varying forms. Most Orthodox Jews remain untroubled by some aspects of this tension, understanding that Judaism’s affirmation of chosenness and hierarchy can inspire and ennoble without denigrating others. In other instances, affirmations of metaphysical differences between Jews and gentiles can take a form that makes many of us uncomfortable, but we have the legitimate option of regarding them as non-authoritative. Finally and most disturbing, there are positions affirmed by standard halakhic sources from the Talmud to the Shulhan Arukh that apparently stand in stark contrast to values taken for granted in the modern West and taught in other sections of the Torah itself. Let me begin with a few brief observations about the first two categories and proceed to somewhat more extended ruminations about the third. Critics ranging from medieval Christians to Mordecai Kaplan have directed withering fire at the doctrine of the chosenness of Israel. Nonetheless, if we examine an overarching pattern in the earliest chapters of the Torah, we discover, I believe, that this choice emerges in a universalist context. The famous statement in the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 4:5) that Adam was created singly so that no one would be able to say, “My father is greater than yours” underscores the universality of the original divine intent. While we can never know the purpose of creation, one plausible objective in light of the narrative in Genesis is the opportunity to actualize the values of justice and lovingkindness through the behavior of creatures who subordinate themselves to the will 1 of God. -

Conversion to Judaism Finnish Gerim on Giyur and Jewishness

Conversion to Judaism Finnish gerim on giyur and Jewishness Kira Zaitsev Syventävien opintojen tutkielma Afrikan ja Lähi-idän kielet Humanistinen tiedekunta Helsingin yliopisto 2019/5779 provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Tiedekunta – Fakultet – Faculty Koulutusohjelma – Utbildningsprogram – Degree Programme Humanistinen tiedekunta Kielten maisteriohjelma Opintosuunta – Studieinriktning – Study Track Afrikan ja Lähi-idän kielet Tekijä – Författare – Author Kira Zaitsev Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Conversion to Judaism. Finnish gerim on giyur and Jewishness Työn laji – Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä– Sidoantal Arbetets art – Huhtikuu 2019 – Number of pages Level 43 Pro gradu Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Pro graduni käsittelee suomalaisia, jotka ovat kääntyneet juutalaisiksi ilman aikaisempaa juutalaista taustaa ja perhettä. Data perustuu haastatteluihin, joita arvioin straussilaisella grounded theory-menetelmällä. Tutkimuskysymykseni ovat, kuinka nämä käännynnäiset näkevät mitä juutalaisuus on ja kuinka he arvioivat omaa kääntymistään. Tutkimuseni mukaan kääntyjän aikaisempi uskonnollinen tausta on varsin todennäköisesti epätavallinen, eikä hänellä ole merkittäviä aikaisempia juutalaisia sosiaalisia suhteita. Internetillä on kasvava rooli kääntyjän tiedonhaussa ja verkostoissa. Juutalaisuudessa kääntynyt näkee tärkeimpänä eettisyyden sekä juutalaisen lain, halakhan. Kääntymisen nähdään vahvistavan aikaisempi maailmankuva -

Symbols in the Book of Revelation and Their Literal Meaning According to Other Passages of Scripture

Symbols in the Book of Revelation and Their Literal Meaning According to Other Passages of Scripture One vital basic rule of bible study is to compare Scripture with In the Footsteps of John: Scripture. Isaiah 28:9-10 “Whom shall He teach knowledge? And whom shall Walking through the Book of Revelation He make to understand doctrine? Them that are weaned from the milk, and drawn from the breasts. For precept must be upon precept, precept with John the Revelator upon precept; line upon line, line upon line; here a little, and there a little”. www.lrhartley.com/john 1 Corinthians 2:13 “Which things also we speak, not in the words which man’s wisdom teacheth, but which the Holy Ghost teacheth; comparing spiritual things with spiritual”. The prophecies of the book of Revelation have only 2 Timothy 3:16-17 “All scripture is given by inspiration of God, and one correct interpretation, and there is only one way to is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in discover it: allow the bible to interpret itself. righteousness: that the man of God may be perfect, thoroughly furnished unto all good works”. Angel Messenger ........................................................................ Daniel 8:16, 9:21; Luke 1:19,26; Hebrews 1:14 Ark of Testimony Ark of covenant; The mercy seat where God dwells ....... Exodus 25:10-22; Psalm 80:1 Babylon Religious apostasy; confusion ......................................... Genesis 10:8-10, 11:6-9: Revelation 18:2,3; 17:1-5 Balaam, Doctrine of Balaam Advancing our own interests, compromise, idolatry ....... Numbers 22:5-25 Beast Kingdom, government, political power .......................... -

Major Lessons from the Minor Prophets Micah: Who Is Like God?

Major Lessons from the Minor Prophets Micah: Who Is Like God? Micah 7:18-20 (ESV) 18 Who is a God like you, pardoning iniquity and passing over transgression for the remnant of his inheritance? He does not retain his anger forever, because he delights in steadfast love. 19 He will again have compassion on us; he will tread our iniquities underfoot. You will cast all our sins into the depths of the sea. 20 You will show faithfulness to Jacob and steadfast love to Abraham, as you have sworn to our fathers from the days of old. “Micah” = Attributes of God’s character we have seen already in Micah: _____________________ Micah 1:2-3 (ESV) 2 Hear, you peoples, all of you; pay attention, O earth, and all that is in it, and let the Lord GOD be a witness against you, the Lord from his holy temple. 3 For behold, the LORD is coming out of his place, and will come down and tread upon the high places of the earth. _____________________ Micah 1:4-6 (ESV) 4 And the mountains will melt under him, and the valleys will split open, like wax before the fire, like waters poured down a steep place. 5 All this is for the transgression of Jacob and for the sins of the house of Israel. What is the transgression of Jacob? Is it not Samaria? And what is the high place of Judah? Is it not Jerusalem? 6 Therefore I will make Samaria a heap in the open country, a place for planting vineyards, and I will pour down her stones into the valley and uncover her foundations. -

Session 6 the Forerunner Message in Isaiah 18-19

INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PRAYER UNIVERSITY - MIKE BICKLE Forerunner Study Track: The Forerunner Message in Isaiah 1-45 Session 6 The Forerunner Message in Isaiah 18-19 I. THE CONTEXT OF ETHIOPIA AND EGYPT IN THE END TIMES (DAN. 11:42-43) A. The Antichrist will attack Egypt and gain control over Ethiopia (Dan. 11:42-43). Ultimately, Jesus will destroy the Antichrist’s armies and will redeem Ethiopia (Isa. 18:7) and Egypt (Isa. 19:16-25). 42He [Antichrist] shall stretch out his hand against…Egypt…43He shall have power over the treasures of gold and silver…also the…Ethiopians shall follow at his heels [cooperate with him]. (Dan. 11:42-43) 1. Egypt will be temporarily occupied by the Antichrist’s military forces, giving the Antichrist control of their national finances resources. 2. The Ethiopians “shall follow at his heels,” or be in step, in cooperation, with the Antichrist. 3. The Antichrist shall invade the Glorious Land of Israel (11:45). He will plant part of his headquarters around Jerusalem. The “glorious holy mountain” speaks of the temple site in Jerusalem. The two seas are the Mediterranean Sea (in the west) and the Dead Sea (in the east). 45“And he [Antichrist] shall plant the tents of his palace between the seas [Mediterranean Sea and the Dead Sea] and the glorious holy mountain [Jerusalem]...” (Dan. 11:45) B. Outline 18:1-3 Instructions for the ambassadors sent to and from Ethiopia 18:4-6 God’s message for Ethiopia and the nations 18:7 The Ethiopians will worship the Lord in Jerusalem C. -

Sermon Notes & References “Two Destinies” Isaiah 65:1-16 June 17

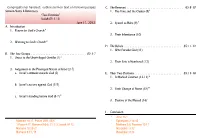

Congregational handout; outline sermon text on following pages C. The Remnant . 65:8-10 Sermon Notes & References 1. The Vine and the Cluster (8) E “Two Destinies” Isaiah 65:1-16 June 17, 2012 2. Spared as Heirs (9) F A. Introduction 1. Prayer for God’s Church A 3. Their Inheritance (10) 2. Warning to God’s Church B D. The Rebels . 65:11-12 1. Who Forsake God (11) B. The Two Groups . 65:1-7 1. Grace to the Unprivileged Gentiles (1) C 2. Their Fate is Numbered (12) 2. Judgement of the Privileged Nation of Israel (2-7) a. Israel’s attitude towards God (2) E. Their Two Destinies . 65:13-16 1. A Marked Contrast (13-14) G b. Israel’s actions against God (3-5) 2. Their Change of Name (15) H c. Israel’s standing before God (6-7) D 3. Destiny of the Blessed (16) I F. Conclusion E John 15:1 A Matthew 18:17, Psalm 28:9, 85:6 F Ephesians 2:14-16 B 1 Peter 4:17; Romans 9:6-8; 11:1, 5; Isaiah 64:12 G Matthew 5:6, Romans 10:11 C Romans 10:20-21 H Revelation 3:12 D Romans 3:11, 15 I Revelation 3:14 —{1}. Isaiah 65:1-16. Two Destinies A. Introduction 1. Prayer for God’s Church a. that word ‘church’ in the NT is used to translate the Greek word ekklesia, from which you will recognize we get our English word ‘ecclesiastical’, the name of the OT book, ‘Ecclesiastes’, and so forth b. -

Micah at a Glance

Scholars Crossing The Owner's Manual File Theological Studies 11-2017 Article 33: Micah at a Glance Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Article 33: Micah at a Glance" (2017). The Owner's Manual File. 13. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/owners_manual/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theological Studies at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Owner's Manual File by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MICAH AT A GLANCE This book records some bad news and good news as predicted by Micah. The bad news is the ten northern tribes of Israel would be captured by the Assyrians and the two southern tribes would suffer the same fate at the hands of the Babylonians. The good news foretold of the Messiah’s birth in Bethlehem and the ultimate establishment of the millennial kingdom of God. BOTTOM LINE INTRODUCTION QUESTION (ASKED 4 B.C.): WHERE IS HE THAT IS BORN KING OF THE JEWS? (MT. 2:2) ANSWER (GIVEN 740 B.C.): “BUT THOU, BETHLEHEM EPHRATAH, THOUGH THOU BE LITTLE AMONG THE THOUSANDS OF JUDAH, YET OUT OF THEE SHALL HE COME FORTH” (Micah 5:2). The author of this book, Micah, was a contemporary with Isaiah. Micah was a country preacher, while Isaiah was a court preacher. -

Edward J. Young, "Isaiah 34 and Its Position in the Prophecy," Westminster Theological Journal 27.2 (May 1965): 93-114

ISAIAH 34 AND ITS POSITION IN THE PROPHECY EDWARD J. YOUNG N THE structure of Isaiah's prophecy chapter 34 occupies I ~ pivotal position!1 Gesenius was one of the first to suggest identity of authorship with chapters 13-14.2 Ewald, however, attributed the chapter to the writer of Jeremiah 50-51,3 and Duhm sought to combine these two views.4 Kissane declares that not even the most conservative critics (and among these he ranks Feldmann and Fischer) will attribute the poem to Isaiah, but he, himself, seems to think that Isaiah may be the author,s and advances some considerations against a post exilic date.6 Torrey makes the chapter the beginning of the I For a recent discussion of the relation of this chapter to what follows cf. Marvin Pope: "Isaiah 34 In Relation To Isaiah 35, 40-66" in Journal of Biblical Literature, vo!. 71, 1952, pp. 235-243. • Gesenius (Commentar iiber den Jesaia, Leipzig, 1821, pp. 908 f.) held that both 34 and 35, like 40-66, clearly belong to the last period of the exile. This position "bedarf ... keines ausfiihrlichen Beweises". These two chapters therefore have a close relationship with other passages from the same period such as 13 and 14, and this renders the identity of author ship probable. Gesenius compares 34:4 with 13:9, 10; 24:19 ff.; 34:11 ff. and 13:20-22; 35:2 with 40:5, 9 and 60:1; 35:3-5 with 40:1, 2, 9 and 42:16; 35:6, 7 with 43:19, 20; 48:21 and 49:10, 11; 35:8 with 40:3, 4; 49:11 and 62 :10, etc. -

SBL Press Atlanta Copyright © 2014 by SBL Press

LXX ISAIAH 24:1–26:6 AS INTERPRETATION AND TRANSLATION Press SBL S eptuagint and Cognate Studies Wolfgang Kraus, Editor Robert J. V. Hiebert Karen Jobes Arie van der Kooij Siegfried Kreuzer Philippe Le Moigne Press SBL Number 62 LXX ISAIAH 24:1–26:6 AS INTERPRETATION AND TRANSLATION A METHODOLOGicAL DISCUSSION By Wilson de Angelo Cunha Press SBLSBL Press Atlanta Copyright © 2014 by SBL Press All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, SBL Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cunha, Wilson de Angelo, author. LXX Isaiah 24:1–26:6 as interpretation and translation : a methodological discussion / by Wilson de Angelo Cunha. p. cm. — (Septuagint and cognate studies ; number 62) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-62837-022-5 (paper binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-62837-023-2 (electronic format) — ISBN 978-1-62837-024-9 (hardcover binding : alk. paper) 1. Bible. Isaiah, XXIV-XXVI, 6—Criticism, interpretation, etc. 2. Bible. Old Testa- ment. Greek—Versions—Septuagint. I. Title. II. Series: Septuagint and cognate studies series ; no. 62. BS1515.52.C86 2014 224'.10486—dc23 2014027665 Press Printed on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 SBLstandards for paper permanence. -

E Z E K I E L

E Z E K I E L —prophet to the exiles in Babylon, early sixth century. Name means “God will strengthen” 1. Date Ezekiel dates his prophecies very frequently, as much or more than any other OT book. There are 14 time-posts in Ezekiel, all in chronological order except 29:17 that has a logical connection to its context of Oracles against the Nations: 1:1 30th year (of what?) 1:2 5th year of Jehoiachin’s captivity 8:1 6th “ 20:1 7th 24:1 9th 26:1 11th 29:1 10th 29:17 27th 30:20 11th 31:1 11th 32:1 12th 32:17 12th 33:21 12th year of our captivity 40:1 25th “ Jehoiachin’s captivity started in 597 BC, the apparent terminus a quo: 5th year = 593 BC 27th year = 571 BC Note that many of these prophecies were given during his 11th and 12th years of captivity. That would be 587-586 BC, just during and after the fall and destruction of Jerusalem (cf. 33:21). Ezekiel 1:1 poses a question: the “30th year” of what? It could be the 30th year of the Neo-Babylonian empire (about 596 BC, assuming its beginnings under Nabopolassar in 626 BC), the year after Jehoiachin was taken captive, two years before Ezekiel’s call related in chapter 1. Another possibility is that it is Ezekiel’s age at the time of his call (cf. Num. 4:3, and the lives of John the Baptist and of Jesus, Lk. 3:23). The old critical view of C.