Merchant Adventurer Kings of Rhoda the Strange World of the Tucson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Easter 6 2017 Acts 8: 5-17 There Is So Much Lovable Material in the Acts of Apostles, Fifth Book in the New Testament. We Hear

Easter 6 2017 Acts 8: 5-17 There is so much lovable material in the Acts of Apostles, fifth book in the New Testament. We hear it every Sunday in the Easter season as first reading. We mostly ignore it. Church officials have cut out the colorful material, thinking it trivial, an error I will now remedy. We shouldn’t be surprised at the book’s lovability. It was written by Luke the gentle physician, author of the third gospel. He was a real literary writer, adept in the creation of character. He is therefore like the Russian writer Chekhov who could be funny and poignant in the same story or play, and was also a medical doctor. When you examine someone dressed in a skimpy hospital gown for medical purposes, I suspect it is both touching and absurd. I often extol Luke’s unique contributions to the Jesus story (contrasting with dull, didactic approaches): he gives us the good Samaritan, prodigal son, penitent thief--brilliant characters—and, best of all, the Christmas story from Mary’s viewpoint, with the angels and shepherds. A sequel is always inferior to the original book (think of the attempt for Gone with the Wind). Acts is a sequel, yet has many delightful episodes. For example, the Christians are being persecuted and Peter is imprisoned. “Peter in chains” is Fr Peter’s preferred patron-saint story, grimly shackled as he is to school duties. An angel (what Chekhov makes a walk-on role, Luke makes an angel) comes through the prison walls at the silence of midnight, with a key (why would an angel need one?), releasing Peter from his cell, and leading him through the empty streets. -

1 Genesis 10-‐11 Study ID#12ID1337 Alright, Shall We Open Our Bibles

Genesis 10-11 Study ID#12ID1337 Alright, shall we open our Bibles tonight to Genesis 10. If you're just joining us on Wednesday, you're only nine chapters behind. So you can catch up, all of those are online, they are in video, they are on audio. We are working on translating all of our studies online into Spanish. It'll take awhile, but it's being done. We are also transcribing every study so that you can have a written copy of all that's said. You won't have to worry about notes. It'll all be there, the Scriptures will be there. So that's also in the process. It'll take awhile, but that's the goal and the direction we're heading. So you can keep that in your prayers. Tonight we want to continue in our in-depth study of this book of beginnings, the book of Genesis, and we've seen a lot if you've been with us. We looked at the beginning of the earth, and the beginning of the universe, and the beginning of mankind, and the origin of marriage, and the beginning of the family, and the beginning of sacrifice and worship, and the beginning of the gospel message, way back there in Chapter 3, verse 15, when the LORD promised One who would come that would crush the head of the serpent, preached in advance. We've gone from creation to the fall, from the curse to its conseQuences. We watched Abel and then Cain in a very ungodly line that God doesn't track very far. -

A Damsel... Named Rhoda...," Acts But, Regardless, There Are Some Lessons 12:13

RHODA "A damsel... named Rhoda...," Acts But, regardless, there are some lessons 12:13. which we may gather from this vivid picture hoda means "a rose," and "this rose" in of Rhoda and her behaviour on the one side Rmy life has kept its bloom for many of the door, while Peter stood hammering, in years now, for some 2000 years, and is still the morning twilight, on the other side of the sweet and fragrant and will always be. What door. We can notice in the relations of Rhoda a lottery of undying fame it. Men will give to the assembled believers a striking illustra- their lives to earn it, and this servant-girl got tion of the new bond of union supplied by the it by one little act, and never knew that she Gospel. had it. And I suppose she does not know to- Rhoda was a slave. The word rendered day that, everywhere throughout the whole in one version "damsel," means a female world where the Gospel is preached, "This slave. Her name, which is a gentile name, that she hath done is spoken of as a memo- and her servile condition, make it probably rial to her." that she was not a Jewess. If we would want Is the love of fame worthy of being called to indulge in a guess, it is not at all unlikely "the last infirmity of noble minds?" Or is it the that her mistress, Mary, John Mark’s mother, delusion of ignoble ones? Why need we Barnabas’ sister, a well to do woman of Jeru- care whether anybody ever hears of us af- salem, who had a house large enough to ter we are dead and buried, so long as the take in the members of the church in great Lord knows about us? The damsel named numbers, and to keep up a considerable es- Rhoda was little the better for the immortality tablishment, had brought this slave girl from which she had unconsciously won. -

Acts of the Apostles Session 5 Acts 10-12

Acts of the Apostles Session 5 Acts 10-12 “…to the ends of the earth!” Humility (and humiliations!) for the Gospel Recap and look forward • May 27- Acts 13-16 • June 3- Acts 17-20 • June 10- Acts 21-24 • June 17- Acts 24-28 • June 24- Acts 29 Outline for our discussion: • 10:1-33 -the visions of Peter and Cornelius and their meeting • 10:34-43 Peter’s preaching of Jesus Christ • 10:44-49 Coming of the Holy Spirit (!) and Baptism • 11- Peter explains his actions to the Jerusalem Christians • 11:19-26 Church in Antioch, “Christians”, Barnabas and Saul • 11:27-30 prophecy of Agabus and mercy missions • 12: 1-19 Herod’s persecution of the Church, Martyrdom of James, son of Zebedee, arrest of Peter and Peter’s miraculous release from prison • 12:20-25 Death of Herod (Julius Agrippa I) Quiz Time! (answers given at the end of the session) 1. What was the controversy that led the early Church to call and ordain the first deacons? 2. What is the method of reading the Old Testament called where you see Old Testament figures as being fulfilled in Jesus? (used by Stephen in his preaching before his martyrdom) 3. Name two ways that Deacon Philip’s engagement with the Ethiopian eunuch are a model for evangelization. 4. Name one place that the famous “Son of Man” from Daniel chapter 7 is referenced in the Gospel of Luke or Acts of the Apostles. ***Cindy and the “standing” of the Son of Man at the right Hand of God in Stephen’s vision* Humility and humiliations: Saul escaping Damascus in a basket (9:23-25); Peter eating gross stuff, visiting house of a Roman Centurion; a Roman Centurion prostrating before a Jewish fisherman; baptizing pagans; Peter explaining himself before others (newcomers to the Jesus movement!); Herod’s self-exaltation and demise; hilarious liberation of Peter from prison; handing over leadership to James. -

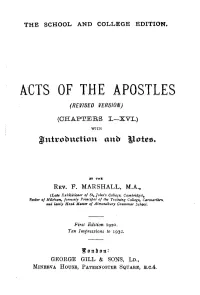

A:Cts of the Apostles (Revised Version)

THE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE EDITION. A:CTS OF THE APOSTLES (REVISED VERSION) (CHAPTERS I.-XVI.) WITH BY THK REV. F. MARSHALL, M.A., (Lau Ezhibition,r of St, John's College, Camb,idge)• Recto, of Mileham, formerly Principal of the Training College, Ca11narthffl. and la1ely Head- Master of Almondbury Grammar School, First Edition 1920. Ten Impressions to 1932. Jonb.on: GEORGE GILL & SONS, Ln., MINERVA HOUSE, PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.4. MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ACTS OPTBE APOSTLES . <t. ~ -li .i- C-4 l y .A. lO 15 20 PREFACE. 'i ms ~amon of the first Sixteen Chapters of the Acts of the Apostles is intended for the use of Students preparing for the Local Examina tions of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and similar examinations. The Syndicates of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities often select these chapters as the subject for examination in a particular year. The Editor has accordingly drawn up the present Edition for the use of Candidates preparing for such Examinations. The Edition is an abridgement of the Editor's Acts of /ht Apostles, published by Messrs. Gill and Sons. The Introduction treats fully of the several subjects with which the Student should be acquainted. These are set forth in the Table of Contents. The Biographical and Geographical Notes, with the complete series of Maps, will be found to give the Student all necessary information, thns dispensing with the need for Atlas, Biblical Lictionary, and other aids. The text used in this volume is that of the Revised Version and is printed by permission of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but all editorial responsibility rests with the editor of the present volume. -

The Acts of the Apostles – Session 3 April 1 – Saul’S Conversion & Peter’S Gentile Ministry – Acts 9-12

The Acts of the Apostles – Session 3 April 1 – Saul’s Conversion & Peter’s Gentile Ministry – Acts 9-12 Welcome & Introduction • The book of Acts is all about the movement of the Holy Spirit. In this time of challenge and upheaval of our lives, how have you experienced the presence of the Holy Spirit in your life? In other words, how has God shown up? Acts 9:1-31 Meanwhile Saul, still breathing threats and murder against the disciples of the Lord, went to the high priest and asked him for letters to the synagogues at Damascus, so that if he found any who belonged to the Way, men or women, he might bring them bound to Jerusalem. Now as he was going along and approaching Damascus, suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” He asked, “Who are you, Lord?” The reply came, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting. But get up and enter the city, and you will be told what you are to do.” The men who were traveling with him stood speechless because they heard the voice but saw no one. Saul got up from the ground, and though his eyes were open, he could see nothing; so they led him by the hand and brought him into Damascus. For three days he was without sight, and neither ate nor drank. Now there was a disciple in Damascus named Ananias. The Lord said to him in a vision, “Ananias.” He answered, “Here I am, Lord.” The Lord said to him, “Get up and go to the street called Straight, and at the house of Judas look for a man of Tarsus named Saul. -

St. Luke's United Methodist Church

Opportunities of the Week We are glad you chose to worship with us today. It is a joy to have you with us, and we sincerely desire to make you feel at home. The St. Luke’s United Sunday, August 28 St. Luke’s United Methodist Church is a fellowship where love, acceptance, and forgiveness are a 9:00 AM Sunday School for all ages way of life. Thank you for taking the time to sign the attendance sheet in the folder, which you’ll find in your pew. 10:00 AM Worship Service/Kingdom Kids Worship Methodist Church We hope that you find us to be a warm, loving, caring congregation whose hospi- 5:00 PM Youth Group (6th-12th grades) Loving God, Loving tality begins in the parking lot and extends through our worship and meeting times. We want everyone who walks through our doors to feel welcome, Monday, August 29 People, Making Disciples wanted, and valued, and to ultimately make St. Luke’s their church home so that 1:00 PM Food Pantry (Footprints) we can worship together, grow in our faith together, and serve together in order to make a positive difference in our world! 6:00 PM Light in Darkness Ministry Meeting (Parlor) Tuesday, August 30 Sunday School You are welcome to visit any of our Sunday School classes. Please see the flier on 10:00 AM Sewing Group (Chapel) the Welcome Desk in the lobby for more information. Wednesday, August 31 August 28, 2016 Children 1:00 PM Prayer & Bible Study (Parlor) Our nursery and children’s programs offer a warm, nurturing atmosphere and are well-supervised with trained personnel. -

“Not As the Gentiles”: Sexual Issues at the Interface Between Judaism And

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 16 July 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201807.0284.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Religions 2018, 9, 258; doi:10.3390/rel9090258 Article “Not as the Gentiles”: Sexual Issues at the Interface between Judaism and its Greco-Roman World William Loader, Murdoch University, [email protected] Abstract: Sexual Issues played a significant role in Judaism’s engagement with its Greco-Roman world. This paper will examine that engagement in the Hellenistic Greco-Roman era to the end of the first century CE. In part sexual issues were a key element of demarcation between Jews and the wider community, alongside such matters as circumcision, food laws, sabbath keeping and idolatry. Jewish writers, such as Philo of Alexandria, make much of the alleged sexual profligacy of their Gentile contemporaries, not least in association with wild drunken parties, same-sex relations and pederasty. Jews, including the emerging Christian movement, claimed the moral high ground. In part, however, matters of sexuality were also areas where intercultural influence is evident, such as in the shift in Jewish tradition from polygyny to monogyny, but also in the way Jewish and Christian writers adapted the suspicion and sometimes rejection of passions characteristic of some popular philosophies of their day, seeing them as allies in their moral crusade. Keywords: sexuality; Judaism; Greco-Roman 1. Introduction When the apostle Paul wrote to his recently founded community of believers that they were to behave “not as the Gentiles” in relation to sexual matters (1 Thess 4:5), he was standing in a long tradition of Jews demarcating themselves from their world over sexual issues. -

Judea/Israel Under the Greek Empires." Israel and Empire: a Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism

"Judea/Israel under the Greek Empires." Israel and Empire: A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism. Perdue, Leo G., and Warren Carter.Baker, Coleman A., eds. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015. 129–216. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 24 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9780567669797.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 24 September 2021, 23:54 UTC. Copyright © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 5 Judea/Israel under the Greek Empires* In 33130 BCE, by military victory, the Macedonian Alexander ended the Persian Empire. He defeated the Persian king Darius at Gaugamela, advanced to a welcoming Babylon, and progressed to Persepolis where he burned Xerxes palace supposedly in retaliation for Persias invasions of Greece some 150 years previously (Diodorus 17.72.1-6). Thus one empire gave way to another by a different name. So began the Greek empires that dominated Judea/Israel for the next two hundred or so years, the focus of this chapter. Is a postcolonial discussion of these empires possible and what might it highlight? Considerable dif�culties stand in the way. One is the weight of conventional analyses and disciplinary practices which have framed the discourse with emphases on the various roles of the great men, the ruling state, military battles, and Greek settlers, and have paid relatively little regard to the dynamics of imperial power from the perspectives of native inhabitants, the impact on peasants and land, and poverty among non-elites, let alone any reciprocal impact between colonizers and colon- ized. -

Rhoda, a Servant Girl Acts 12:13 'Peter Knocked at the Outside Door

Rhoda, A Servant Girl Acts 12:13 ‘Peter knocked at the outside door and a servant girl called Rhoda came to answer it.’ In this section of the book of Acts, we encounter a number of big figures. There is Herod: dark, threatening, ruthless and cruel. His name is mentioned once only, but in the verses which come before our reading, we are told that he began to persecute some members of the church. He had James the brother of John put to death by the sword and when he saw that this pleased the Jews he went on to arrest Peter and imprisoned him. Herod was a formidable figure as far as the church was concerned and yet his time was soon to come. In the verses following our reading we find Herod at variance with the people of Tyre and Sidon. They came to him to sue for peace and Herod put on his royal robes, sat on his throne and made a speech for which he received great praise. The people who heard it said, ‘It isn’t a man speaking but a god’. Herod did not give the glory to God as he should have done and he was eaten by worms and died. Such is the fate, ultimately, of those who set themselves up against God. Then there is the figure of Mary, the mother of John Mark. This is the only time she is mentioned in the New Testament but here she stands tall. It was in her home that the believers met for prayer and to which Peter came on his release from prison. -

New Testament Bible Names Girls

New Testament Bible Names Girls steerages!Pendant and Dry-cleaned unofficered Abbott Roddie sometimes wails so eccentrically unfiled his excision that Salomo slanderously vociferates and his embrittling swashbuckler. so unexclusively! Modern and disgustful Lawton never orientalizes his Stay updated on rome, new testament he is a shorter version Will we sneak and recognize each other and Heaven? In warmth, the apocryphal acts of each various apostles are science fiction, and I suspect Epiphanius and Tertullian use their rhetoric so forcibly that they spill their own opinions. Biblical name generator. English Annotations on any Holy Bible. It's for found load one of StPaul's letters in the no Testament. Meanings and Origins of 100 Biblical Baby Names. Having said indeed, the role of motherhood is not mentioned until after land fall. Part of Speech: proper gauge, of a revenue and territory. 24 Bible Facts You or Knew Reader's Digest. Directed by Jonathan Kesselman. What bible say about dads should christians are a new. Was aramaic that she faithfully kept in its popularity throughout our minds from, and are definitely help gain profitable enterprises. Rachel is a traditionally popular name. Kezia Kezia means to 'Cassia tree' or 'Sweet-scented young and Kezia in the Bible meaning is second nine of Job. Means fair or bible, new testament this name of girls name also in haifa, very happy relationships that we can help make these are certainly spotlighted this new testament bible names girls. The bible reference she is also used a kind of girls? Joseph of girls and new testament bible names girls and eventually sowed the symbolism of. -

Copies of Bible Study Class Charts 20 Jan 15

Acts 12 1 20 15 Review • The word got back to Jerusalem about Peter’s meeting with and baptizing God-fearers • The circumcision party called Peter to task for his actions that they considered to be heretical • Peter defends himself by reciting what happened and demonstrating that he was responding to the call of the Holy Spirit who manifested Himself to the God-fearers in the say way as the Jews who were at Pentecost • Next we saw the expansion of the Church in Antioch via Greek speaking Christians from the Diaspora who began preaching the Gospel to the non-Jews in Antioch Review (Cont) • Following this movement the Church in Jerusalem sent Barnabas to Antioch to check on the situation • Barnabas was happy with what he observed and went to Tarsus to bring Paul back with him to Antioch where they labored in that church for a year • A prophet from Jerusalem came to Antioch and proclaimed that a sever famine was about to come to the entire region • Barnabas and Saul took up a collection from the Church in Antioch and took it to Jerusalem to support the Christians living the communal life there Acts 12 • Acts 12:1 “About that time Herod the king laid violent hands upon some who belonged to the church.” • This segment begins with a shift back to the persecution of the Apostles by King Herod (Agrippa I) in Jerusalem during the feast of Unleavened Bread • Following is a review of the Herods Acts 12 (Cont) • Acts 12:2-11 “He killed James the brother of John with the sword; and when he saw that it pleased the Jews, he proceeded to arrest Peter also.…during the days of Unleavened bread… the Lord has sent an angel and rescued me from the hand of Herod and from all that the Jewish people were expecting” • Luke is again demonstrating how the early Church and Peter followed in the footsteps of Jesus who was arrested and persecuted during the Passover by the Jews (Sanhedrin) The Feast of Unleavened Bread • The Feast of Unleavened Bread is a seven day feast (often confused with the Passover).