Final Thesis Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking for Podcast Suggestions? We’Ve Got You Covered

Looking for podcast suggestions? We’ve got you covered. We asked Loomis faculty members to share their podcast playlists with us, and they offered a variety of suggestions as wide-ranging as their areas of personal interest and professional expertise. Here’s a collection of 85 of these free, downloadable audio shows for you to try, listed alphabetically with their “recommenders” listed below each entry: 30 for 30 You may be familiar with ESPN’s 30 for 30 series of award-winning sports documentaries on television. The podcasts of the same name are audio documentaries on similarly compelling subjects. Recent podcasts have looked at the man behind the Bikram Yoga fitness craze, racial activism by professional athletes, the origins of the hugely profitable Ultimate Fighting Championship, and the lasting legacy of the John Madden Football video game. Recommended by Elliott: “I love how it involves the culture of sports. You get an inner look on a sports story or event that you never really knew about. Brings real life and sports together in a fantastic way.” 99% Invisible From the podcast website: “Ever wonder how inflatable men came to be regular fixtures at used car lots? Curious about the origin of the fortune cookie? Want to know why Sigmund Freud opted for a couch over an armchair? 99% Invisible is about all the thought that goes into the things we don’t think about — the unnoticed architecture and design that shape our world.” Recommended by Scott ABCA Calls from the Clubhouse Interviews with coaches in the American Baseball Coaches Association Recommended by Donnie, who is head coach of varsity baseball and says the podcast covers “all aspects of baseball, culture, techniques, practices, strategy, etc. -

This Version Has the Raw Data in an Appendix)

Accepted for publication in 2020 by the International Journal of Communication, ijoc.org (this version has the raw data in an appendix) Podcasting as Public Media: The Future of U.S. News, Public Affairs and Educational Podcasts PATRICIA AUFDERHEIDE American University, USA DAVID LIEBERMAN The New School, USA ATIKA ALKHALLOUF American University, USA JIJI MAJIRI UGBOMA The New School, USA This article identifies a U.S.-based podcasting ecology as public media, and then examines the threats to its future. It first identifies characteristics of a set of podcasts in the U.S. that allow them to be usefully described as public podcasting. Second, it looks at current business trends in podcasting as platformization proceeds. Third, it identifies threats to public podcasting’s current business practices. Finally, it analyzes responses within public podcasting to the potential threats. It concludes that currently, the public podcast ecology in the U.S. maintains some immunity from the most immediate threats, but that as well there are underappreciated threats to it both internally and externally. Keywords: podcasting, public media, platformization, business trends, public podcasting ecology As U.S. podcasting becomes an increasingly commercially-viable part of the media landscape, are its public-service functions at risk? This article explores that question, in the process postulating that the concept of public podcasting has utility in describing, not only a range of podcasting practices, but an ecology within the larger podcasting ecology—one that permits analysis of both business methods and social practices, one that deserves attention and even protection. This analysis contributes to the burgeoning literature on podcasting by enabling focused research in this area, permitting analysis of the sector in ways that permit thinking about the relationship of mission and business practice sector-wide. -

Podcasting As Public Media: the Future of U.S

International Journal of Communication 14(2020), 1683–1704 1932–8036/20200005 Podcasting as Public Media: The Future of U.S. News, Public Affairs, and Educational Podcasts PATRICIA AUFDERHEIDE American University, USA DAVID LIEBERMAN The New School, USA ATIKA ALKHALLOUF American University, USA JIJI MAJIRI UGBOMA The New School, USA This article identifies a U.S.-based podcasting ecology as public media and then examines the threats to its future. It first identifies characteristics of a set of podcasts in the United States that allow them to be usefully described as public podcasting. Second, it looks at current business trends in podcasting as platformization proceeds. Third, it identifies threats to public podcasting’s current business practices. Finally, it analyzes responses within public podcasting to the potential threats. The article concludes that currently, the public podcast ecology in the United States maintains some immunity from the most immediate threats, but there are also underappreciated threats to it, both internally and externally. Keywords: podcasting, public media, platformization, business trends, public podcasting ecology As U.S. podcasting becomes a commercially viable part of the media landscape, are its public service functions at risk? This article explores that question, in the process postulating that the concept of public podcasting has utility in describing not only a range of podcasting practices, but also an ecology within the larger podcasting ecology—one that permits analysis of both business methods and social practices, and one that deserves attention and even protection. This analysis contributes to the burgeoning literature on Patricia Aufderheide: [email protected] David Lieberman: [email protected] Atika Alkhallouf: [email protected] Jiji Majiri Ugboma: [email protected] Date submitted: 2019‒09‒27 Copyright © 2020 (Patricia Aufderheide, David Lieberman, Atika Alkhallouf, and Jiji Majiri Ugboma). -

Work on CASA-1000 to Kick Off Soon

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:IX Issue No:236 Price: Afs.15 WEDNESDAY. APRIL 01 . 2015 -Hamal 12, 1394 HS www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes White House looks to be more serious to bring the Afghan war to a rational end. Obama wanted to end the mission in Afghanistan before the end of his tenure AT Monitoring Desk KABUL: Following the recent vis- as they are currently engaged in Pakistani Taliban groups as they stan has cut its support to the Af- it of Afghan leaders to the United training and assisting Afghan forc- were being hit by terrorist attacks. ghan Taliban, but there is a much States where the US President es. Rubin went on saying that Pres- The Afghan government has more positive environment there, Barack Obama agreed on slowing ident Obama has yet to change the not seen evidence so far that Paki- he said. down its troop s withdrawal from plan of 2016 complete withdraw- Afghanistan, Philadelphia Inquir- al from Afghanistan. Very clearly er quoted an American analyst, the President wanted to end the KABUL: The ex-President Hamid Karzai talking to tribal elders from Trudy Rubin as saying that Presi- war before leaving his office, she southern Uruzgan province at his office on Tuesday. The elders expressed dent Obama is overeager to leave said. Terming Afghan forces brave concerns over reactivation of Bagram prison. Afghanistan. President Ashrf and capably Rubin said that they Ghani and CEO Dr. Abdullah Ab- still needed US help with air, in- dullah trip to Washington last week telligence, and logistic support, as had opened a new chapter in bilat- well as financing after 2016. -

Audio and Podcasting Fact Sheet

NUMBERS, FACTS AND TRENDS SHAPING YOUR WORLD ABOUT FOLLOW MY ACCOUNT DONATE Journalism & Media ARCH MENU RESEARCH AREAS FACT HT JUN 16, 2017 Audio and Podcasting Fact Sheet MOR FACT HT: TAT OF TH NW MDIA Audience conomic The audio news sector in the U.S. is split by modes of delivery: traditional terrestrial (AM/FM) radio and digital formats such as online radio and podcasting. While terrestrial radio reaches almost the entire U.S. population and Ownerhip remains steady in its revenue, online radio and podcasting audiences have continued to grow over the last decade. Explore the patterns and longitudinal data about audio and podcasting below. Data on public radio is available in a Find out more separate fact sheet. Audience The audience for terrestrial radio remains steady and high: In 2016, 91% of Americans ages 12 or older listened to terrestrial radio in a given week, according to Nielsen Media Research data published by the Radio Advertising Bureau, a figure that has changed little since 2009. (Note: This and most data on the radio sector apply to all types of listening and do not break out news, except where noted.) Weekl terretrial radio litenerhip Chart Data hare med % of Americans ages 12 or older who listen to terrestrial (AM/FM) radio in a given week Year % of American age 12 or older who liten to terretrial (AM/FM) radio in a given week 2009 92% 2010 92% 2011 93% 2012 92% 2013 92% 2014 91% 2015 91% 2016 91% ource: Nielen Audio RADAR 131, Decemer 2016, pulicl availale via Radio Advertiing ureau. -

General Manager's Newsletter | June 2021

General Manager's Newsletter | June 2021 WPM on TV! Many public radio networks run spots on sister public television stations to build awareness for radio and to reach audiences that perhaps don’t listen to or know about public radio in their communities. WPM and Wyoming PBS initiated a swap. WPM airs messages about Wyoming PBS’s streaming service that brings public television to audiences who don’t get Wyoming PBS in their area. WPM gets a spot right next to Wyoming PBS’s popular Masterpiece, promoting the availability of public radio throughout Wyoming. Let there be no doubt that both services are seriously dedicated to reaching every nook and cranny in Wyoming! Take a look at WPM’s short message here. You’ll be hearing a new national voice on Morning Edition. A Martínez has been appointed host of NPR’s Morning Edition and Up First, joining Rachel Martin, Noel King and Steve Inskeep in the hosting lineup. He will start on July 6, and NPR will be announcing his first day on-air in the coming weeks. He will be based with the team at NPR West. In reflecting on the new role, A notes, “Nine years ago, I had never listened to public radio. I was about to start a new path that would change my career, and in a deeper way, my perspective on life. The time I’ve spent at KPCC proves that public radio journalism can be accessible, relatable and understandable to ANYONE, regardless of their background or educational pedigree. I’m excited to bring every experience I’ve had along the way to NPR and to represent Los Angeles and California the best way I can.” The Metropolitan Opera draws the curtain on another incredible Act! Mary Jo Heath has spent 15 years at the Met. -

How to Listen to Podcasts

How to Listen to Podcasts Podcasts are radio programs that you can access on demand. For every interest, you can find several podcasts: true crime, news, sports, fictional stories, soap operas, etc. All you need is a smartphone or tablet! 1. Find your device’s app store. For Apple products, it’s called the App Store. For Google and Android, it’s called Google Play. 2. Search for Podcast, and you can download the Podcast app for your device. Other podcast apps include Stitcher, Overcast, TuneIn, Spotify, and many more. 3. Once the app is downloaded, open it to start searching for podcasts. 4. When you find a podcast to listen to, you listen to it or download it for later. If you enjoy the episode, you can tap on the Subscribe button to receive new episodes as they are published. Listening in the Car All you need is your device And an Auxiliary Audio Cable Plug on end of the cable into your device and the other end of the cable into your car’s AUX outlet to enjoy podcasts in your car! Parts of a Podcast Subscribe — Ensures you get each episode as it comes out. Add Episode — Allows you to add individual episodes to your list. Download — Downloads the episode to your device. Ratings and Reviews—Where you can share your thoughts on the show. Some Popular Podcasts If you enjoy true crime and mysteries, try Serial, Serial Killers, Cults, Hollywood & Crime, Accused, Criminal, Crimetown, Dirty John, In the Dark, Small Town Murder, Someone Knows Something, The Vanished, Undisclosed, Unsolved Murders, Young Charlie If you enjoy learning about science and social science, try Invisibilia, Criminal, The Allusionist, StoryCorps, Hidden Brain If you enjoy myths and legends, try Lore, Myths & Legends, Astonishing Legends If you enjoy news, try The Daily, Left, Right and Center, Up First, The Editors Other fun podcasts.. -

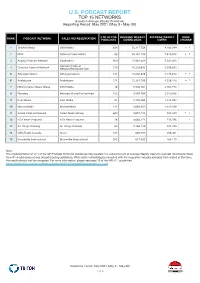

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30)

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30) # OF ACTIVE AVERAGE WEEKLY AVERAGE WEEKLY RANK RANK PODCAST NETWORK SALES REPRESENTATION PODCASTS DOWNLOADS USERS CHANGE 1 Stitcher Media SXM Media 459 35,317,758 9,163,399 1 2 NPR National Public Media 55 35,162,199 7,425,526 1 3 Audacy Podcast Network Cadence13 500 17,982,442 5,542,005 Cumulus Podcast 4 Cumulus Podcast Network Network/Westwood One 270 15,225,592 3,556,832 5 AdLarge/cabana AdLarge/cabana 134 13,050,876 4,173,613 1 6 Audioboom Audioboom 274 12,281,759 4,326,418 1 7 NBCUniversal News Group SXM Media 46 9,926,761 2,764,770 8 Wondery Wondery Brand Partnerships 102 9,589,764 2,910,636 9 Kast Media Kast Media 93 3,795,469 1,514,087 10 WarnerMedia WarnerMedia 114 3,698,251 1,437,168 11 Salem Podcast Network Salem Media Group 662 2,691,743 534,539 1 12 FOX News Podcasts FOX News Podcasts 48 2,665,171 735,796 1 13 All Things Comedy All Things Comedy 52 2,166,142 944,325 14 CBC/Radio-Canada Acast 333 685,707 236,461 15 Bonneville International Bonneville International 252 647,352 184,170 Note: The implementation of v2.1 of the IAB Podcast Technical Guidelines has resulted in a reduced count of Average Weekly Users for podcast downloads made from IP v6 addresses across all participating publishers. While both methodologies complied with the respective industry standard that existed at that time, the results should not be compared. -

Fluency Packet 45

FLUENCY PACKET FOR 4 - 5 GRADE BAND 40 Passages Instructions: The packet below can be used regularly over the course of a school year to help students build fluency. There are enough passages to work on one per week. We recommend that students who need it, practice reading one passage at least 3x daily for a week (15-20 repetitions). 1. First give students the opportunity to listen to a reading by a fluent reader, while “following along in their heads.” It is essential that students hear the words pronounced accurately and the sentences read with proper punctuation attended to! 2. Then have students read the passage aloud while monitored for accuracy. 3. When reading aloud, students should focus on reading at an appropriate pace, reading words and punctuation accurately, and reading with appropriate expression. 4. Students need feedback and active monitoring on their fluency progress. One idea is to do a “performance” toward the end of the week where students are expected to read the selection perfectly and be evaluated. 5. Students need to be encouraged. They know they do not read as well as they ought to and want to. It is very good to explain fluency and explain that it is fixable and has nothing at all to do with intelligence! 6. Students need to know they are obligated to understand what they read at all times. For this reason, comprehension questions and a list of high-value vocabulary words are also included with each passage. After mastery of one passage, students should move on to the next passage and repeat the process. -

Podcasts Shared by Harry Cronson

The Wonderful World of Podcasts Shared by Harry Cronson Podcast Basics Podcasts are episodes of a program available on the internet that enable listeners to enjoy great content from around the world. Most are free. Podcasts allow users to subscribe so that they can automatically receive new programs. If you download a podcast via Wi Fi to storage on your phone memory or if you stream via Wi Fi then you are not using data. If you are listening to a podcast from a website or your phone and you are not connected to Wi Fi, then you are using data. Listening to podcasts is relatively simple. You only need access to the internet and an internet enabled device, such as a smart phone. Find a podcast platform or app that suits you and then sample some of the many thousands of podcasts from around the world. Other features enable you to be in complete control of the listening experience. You can pause and then continue where you left off, skip the commercials, rewind and listen to a part you missed, and play at different speeds. In addition, you can listen with earphones or in some later model hearing aids through Bluetooth (a short-range Wi Fi). On your Computer One way to listen to podcasts is on a web browser like Chrome, Safari or Microsoft Edge. You can do this from a computer or from the web browser on your phone. • For example, in Safari, select Podcast in applications, then Search or Browse in the Podcast window. • Select the podcast you like. -

Percy Dwight Bentley (1885-1968)

NATIONAL ATTENTION: LOCAL CONNECTION La Crosse’s contributions to the Arts and Entertainment in America Compiled by Richard Boudreau, Professor UW-La Crosse, La Crosse, WI 2013 Copyright applied for 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1, Early Poets 5 2. Brick Pomeroy/George W. Peck 9 3. Doc Powell 13 4. Egid Hackner 18 5. Sandor Landau 23 6. Sterling/Dupree 27 7. Percy Bentley 31 8. The Beaches 34 9. Howard Mumford Jones 37 10. Rudolf Kvelve 41 11. Arthur Kreutz 44 12. Walter Ristow 47 13. Joseph Losey 51 14. Alonso Hauser 57 15. Nicholas Ray 61 16. John Toland 73 17. James Cameron 80 18. Don Herbert 85 19. Robert Moevs 89 20. Elmer Petersen 92 21. Frank Italiano/Hugo Jan Huss 96 22. John Judson 100 3 23. Kati Casida 104 24. Arganbright/Weekley 107 25. Charles Dierkop 111 26. John Solie 115 27. Sr. Thea Bowman 119 28. Bill Miller 123 29. Amy Mills 126 30. Scott Thorson 129 4 Compiler’s Notes First--I owe thanks to many people from the past and in the present. All of those people of local importance who recorded their reminiscences for later generations (Egid Hackner and Howard Mumford Jones, for example) and such local historians as David O. Coate, early and long-time professor of English at UW-La Crosse, current teacher and writer, David Marcou, professor of Speech, Charles Haas, and retired librarian, Ed Hill. Most of all, I owe thanks to the great local reporters of the past and present whose original stories and columns I gleaned along the way. -

Top Podcast Companies to Present Winter Podcast Upfront at United

Top podcast companies to present Winter Podcast Upfront at United Talent Agency ESPN, iHeartRadio, NPR, PMM, Stitcher, WNYC Studios and Wondery will bring marquee podcast talent to unveil industry announcements Feb. 13, 2019 LOS ANGELES – Seven of the industry’s top podcast networks will present Winter Podcast Upfront – the first-ever West Coast podcast upfront event – on Feb. 20 at leading global talent and entertainment company United Talent Agency’s headquarters in Beverly Hills. The Winter Podcast Upfront will give advertisers, agencies and media a first look at the newest partnerships, talent and shows slated for 2019. Presentations will feature stars, producers and leading industry executives. Among the highlights planned for the upcoming Winter Podcast Upfront: Stitcher and its advertising arm, Midroll, will be joined by actor and comedian Paul Scheer, who launched his movie critique podcast “Unspooled” on Stitcher’s Earwolf comedy podcast network last year and is the host of Earwolf’s long-running hit show “How Did This Get Made?” Sean Rameswaram, host of “Today Explained,” will also join Stitcher onstage to unveil its expanding slate of partnerships and new and returning shows including “Voyage to the Stars,” “First Day Back” and “LeVar Burton Reads.” NPR podcast hosts Sam Sanders (“It’s Been a Minute”); Kelly McEvers (“Embedded”); and David Greene (“Up First”) discuss creativity, building community with their audiences, the power of audio storytelling and innovation at NPR. NPR’s Senior Vice President of Programming and Audience Development Anya Grundmann will share updates on new seasons of hit podcasts “Invisibilia,” “Embedded” and “Rough Translation,” and with new programming announcements.