Paper (2.670Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guilford Collegian

UBRARY ONLY FOR USE IN THE Guilford College Library Class 'Boo v ' 5 Accessio n \S4o3 Gift FOR USE IN THE LIBRARY ONLY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill http://www.archive.org/details/guilfordcollegia05guil : ' .' •/ ;: ''"V W . r<V iL •<£$%• i - -—-: | tei T'H E - i?i%i^sr r i '' THE GUILFORD COLLEGIAN. OUR TRADE IN Improved New Lee and Patron Cooking Stoves AND NEW LEE AND RICHMOND RANGES Has increased to such an extent that we are now buying them in car load lots. THEY ARE WARRANTED TO BE FIRST QUALITY. Our prices are on the " Live and let live plan," and they account, in part, for the popularity of these Stoves. WMIPCILB!) H)ARP;WAfti <$®» GREENSBORO, N. C. SUMMER VACATION. ILIFF'S Every college man will need to take away in his crip this summer one or two of the latest college song books, which contain all the new and popular University airs We give here the complete list, and any volume will be c ent, postpaid, to any address on receipt of price. THE NEW HARVARD SONG ROOK— All the new Harvard songs of the last three years, with some old favorites. 92 pages. Price $1. 00 postpaid. _ College Songs.—Over 200,000 sold. Containing 91 songs- -all of the old favorites, as well as the new ones: "Don't Forget Dar's a Weddin' To-Night," "DiHe who couldn't Dance,'' "Good-by, my Little Lady," etc Paper, 50 cents. University Songs.—Contains songs of the older colleges — Harvard, Vale, Columbia, Princeton, Rrown, Dartmouth, Williams Bowdoin, Union, and Rutgers Cloth; $2.50. -

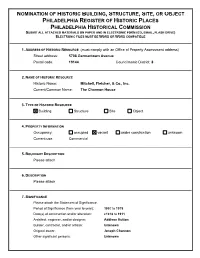

Nomination of Historic Building, Structure, Site, Or Object Philadelphia Register of Historic Places Philadelphia Historical

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address: 5708 Germantown Avenue Postal code: 19144 Councilmanic District: 8 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name: Mitchell, Fletcher, & Co., Inc. Current/Common Name: The Channon House 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use: Commercial 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION Please attach 6. DESCRIPTION Please attach 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): 1857 to 1919 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration: c1818 to 1911 Architect, engineer, and/or designer: Addison Hutton Builder, contractor, and/or artisan: Unknown Original owner: Joseph Channon Other significant persons: Unknown CRITERIA FOR DESIGNATION: The historic resource satisfies the following criteria for designation (check all that apply): (a) Has significant character, interest or value as part of the development, heritage or cultural characteristics of the City, Commonwealth or Nation or is associated with the life of a person significant in the past; or, (b) Is associated with an event of importance to the history of the City, Commonwealth or -

THE CENTURY BUILDING, 33 East 17Th Street and 38-46 East 18Th Street, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 7, 1986; Designation List 186 LP-1539 THE CENTURY BUILDING, 33 East 17th Street and 38-46 East 18th Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1880-1881; architect William Schickel. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 846, Lot 30. On May 14, 1985, the Landmarks Preservation Corrmission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of The Century Building, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Thirty witnesses spoke in favor of designation. Two witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Century Building is a rare surviving Queen Anne style corrmercial building in New York City. Designed by William Schickel and built in 1880- 81, it has been a major presence in Union Square for over a century. Schickel, a German-born architect who practiced in New York, rose to prominence as a leading late-19th century designer of churches and institutional buildings in the United States. He designed the Century Building as a speculative venture for his major clients, the owners of the Arnold Constable department stores. Schickel designed the Century Building in the Queen Anne style, an English import defined by a picturesque use of 17th- and 18th-century motifs. More usually associated in this country with residential architecture, the Queen Anne was also used in commercial buildings, but few of these survive in New York City. -

Rainsford Island: a Boston Harbor Case Study in Public Neglect And

© RAINSFORD ISLAND A Boston Harbor Case Study in Public Neglect and Private Activism First Printing September 3, 2019 Revision December 6, 2020 Copyright: May 13, 2019 William A. McEvoy Jr, & Robin Hazard Ray Dedicated to my wife, Lucille McEvoy 2 © Table of Contents Preface by Bill McEvoy ....................................................................................................................... 4 Introductory Note by Robin Hazard Ray ................................................................................................ 1. The Island to 1854 .................................................................................................................................... 9 2. The Hospital under the Commonwealth, 1854–67 ............................................................................... 14 3. The Men’s Era, 1872–89 ......................................................................................................................... 31 4. The Women’s Era, 1889–95 .................................................................................................................. 43 5. The Infants’ Summer Hospital, 1894–98 ............................................................................................... 60 6. The House of Reformation, 1895–1920 ................................................................................................. 71 7. The Dead of Rainsford Island ........................................................................................................ 94 Epilogue -

Hampden County Memorial Bridge HAER No. MA-114 Spanning the Connecticut River on Memorial Drive Springfield Hampden County Massachusetts

Hampden County Memorial Bridge HAER No. MA-114 Spanning the Connecticut River on Memorial Drive Springfield Hampden County Massachusetts 7 .C PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA • Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Department of the Interior Washington, DC 20013-7127 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD i-spn?, • HAMPDEN COUNTY MEMORIAL BRIDGE HAER No MA-114 Location: Spanning the Connecticut River on Memorial Drive, between the City of Springfield and the Town of West Springfield, Hampden County, Massachusetts UTM: Springfield South, Mass., Quad. 18/466335/6988400 Date of Construction: 1922 Structural Type Seven-span reinforced concrete deck arch bridge Engineer: Fay, Spofford & Thorndike, Boston, engineers Haven & Hoyt, Boston, consulting architects Builder: H.P. Converse & Company Use: Vehicular and pedestrian bridge Previous Owner: Hampden County, Massachusetts Present Owner: Massachusetts Department of Public Works, Boston Significance: The Hampden County Memorial Bridge's main span is the longest concrete deck arch span in Massachusetts. The bridge is a finely-engineered example of a rare self- supporting arch rib reinforcement technique, derived from the Melan tradition. Once encased in concrete, the steel arch reinforcing truss acts as a partner with the concrete in bearing the dead load of the structure. Although the deck is supported on spandrel columns, they are concealed behind a fascia spandrel wall, conveying the Impression of a solid structure. The consulting architects, Haven & Hoyt, embellished the structure with artificial stone, notably in the four pylons of the main channel span. Project Information: Documentation of the Hampden County Memorial Bridge is part of the Massachusetts Historic Bridge Recording Project, conducted during the summer of 1990 under the co-sponsorship of HABS/HAER and the Massachusetts Department of Public Works, in cooperation with the Massachusetts Historical Commission. -

Augustus Saint-Gaudens's the Puritan Founders' Statues, Indian

Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s The Puritan Founders’ Statues, Indian Wars, Contested Public Spaces, and Anger’s Memory in Springfield, Massachusetts Author(s): Erika Doss Source: Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 46, No. 4 (Winter 2012), pp. 237-270 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/669736 Accessed: 28-11-2016 15:01 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms The University of Chicago Press, Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Winterthur Portfolio This content downloaded from 129.74.116.6 on Mon, 28 Nov 2016 15:01:40 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s The Puritan Founders’ Statues, Indian Wars, Contested Public Spaces, and Anger’s Memory in Springfield, Massachusetts Erika Doss Dedicated in 1887 in Springfield, Massachusetts, The Puritan is a large bronze statue of a menacing figure clutching a huge Bible. Commissioned as a memorial to Deacon Samuel Chapin (1595–1675), The Puritan was designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and erected in an urban park surrounded by factories and tenements. -

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts “Hatfield’s Forgotten Industrial Past: The Porter-McLeod Machine Works and the Connecticut Valley Industrial Economy, 1870-1970.” Author: Robert Forrant Source: Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 46, No. 2, Summer 2018, pp. 106-157. Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/number/date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/. 106 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2018 Porter-McLeod Machine Lathe Courtesy of the Hatfield Historical Museum, Hatfield, MA 107 Hatfield's Forgotten Industrial Past: The Porter-McLeod Machine Works and the Connecticut River Valley Industrial Economy, 1870-1970 ROBERT FORRANT Editor’s Introduction: Rural and agricultural Hatfield, Massachusetts, one-time onion capital of the Commonwealth and today known primarily for its potato fields, was once home to a nationally-known gun manufacturer and a thriving machine works company that produced lathes and served customers across the United States and around the world. At its peak, the C. S. Shattuck Arms Company (c. 1875-1910) turned out 15,000 guns annually. The nearby Porter Machine Works (c. 1886-1900), renamed Porter-McLeod Machine Tool Company (c. -

Frank Furness's Library of the University of Pennsylvania and The

"The Happy Employment of Means to Ends" Frank Furness'sLibrary of the University of Pennsylvania and the IndustrialCulture of Philadephia I N 1885 THE PROVOST of the University of Pennsylvania, William Pepper, M.D., called for the construction of a new library building to form the centerpiece of his academic program to incorporate research methods into instruction. Restored in 1991 by Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates and reopened as the university's Fine Arts Library, Frank Furness's building has been cleaned of a century of grime to reveal fiery red hues that highlight its exuberant shapes and forms. Designed with the in- put of the era's best-known library experts, it was initially hailed as the most successful college library of its day. However, its original style caused it to be almost immediately forgotten as a model for other libraries.' Frank Furness is now enjoying a surge of popularity, replacing Henry Hobson Richardson as the best-known American Victorian architect. But even to- day the cognoscenti have trouble understanding what Furness intended in his University of Pennsylvania Library. This article offers an explanation for Furness's masterpiece as a manifestation of the city's innovative indus- trial culture while also providing an important clue to Fumess's success in supposedly conservative Philadelphia. In the 1880s the role of the college library was changing. No longer just 'Much of the research for this paper was undertaken a decade ago as the basis for the restoration of Furness's library at the University of Pennsylvania. It owes much to the early interest in libraries of James F. -

Reading Henry Hobson Richardson's Trains Stations: the Context of Locale

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1994 Reading Henry Hobson Richardson's Trains Stations: The Context of Locale Janel Elizabeth Houton University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Houton, Janel Elizabeth, "Reading Henry Hobson Richardson's Trains Stations: The Context of Locale" (1994). Theses (Historic Preservation). 271. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/271 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Houton, Janel Elizabeth (1994). Reading Henry Hobson Richardson's Trains Stations: The Context of Locale. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/271 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reading Henry Hobson Richardson's Trains Stations: The Context of Locale Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Houton, Janel Elizabeth (1994). Reading Henry Hobson Richardson's Trains Stations: The Context of Locale. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/271 UNIVERSlTYy PENNSYL\^\NL\ UBKARIE5 READING HENRY HOBSON RICHARDSON'S TRAINS STATIONS: THE CONTEXT OF LOCALE Janel Elizabeth Houton A THESIS in Historic FVeservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 1994 ^^U*^A ^ • 2^-^^-^^^ George E. -

Alphabetical Bios

The following individuals are featured in Maine Voices from the Civil War and To the Highest Standard: Maine’s Civil War Flags at the Maine State Museum. They may have owned or used objects, written letters or diaries, or are mentioned by name. MSM volunteers Bob Bennett [RB] and Dave Fuller [DF] researched most of the individuals. Jane Radcliffe [JR] and Laurie LaBar [LL] added information for a few more. MSM numbers refer to the accession number of the artifact in the Maine State Museum collection. A few objects from other collections are included as well. Regimental names have been abbreviated for convenience. Thus, the 3rd Regiment Maine Infantry Volunteers is referred to as the 3rd Maine. If no branch of the service is mentioned, the regiment is infantry. Cavalry and artillery regiments are referred to as such. Austin, Nathaniel Artifact: letter to “cousin Moses,” MSM 68.9 Nathaniel Austin was born December 27, 1803 in Nobleboro, Maine, the youngest of four children of John Austin and Hannah Hall Austin. After Hannah’s 1809 death, John married her sister, Deborah, and they had seven children. One of them was named Moses, which would have made him Nathaniel’s half-brother, not cousin. No other Moses Austin has been found. Nathaniel was also married twice. His first wife was Mary Ann Cotter, and they had six children. Nathaniel’s second wife was Nancy B. Cotter (believed to be Mary Ann’s sister), and they had five children. The Austin and Hall families were sailors, merchants and ship builders in the Mid-Coast area of Maine (Nobleboro, Damariscotta, Newcastle, and Wiscasset). -

Ten Commandments Bible Law Course Moses in Washington D.C

Lesson One - Page 1 The Ten Commandments Bible Law Course Moses in Washington D.C. Exodus 20:3-17 governmental history is recorded in the Bible’s books of Joshua, Judges, Kings and Chronicles. The kings of Israel wrote several books of your Bible; Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes and The Song of Solomon. The prophets, such as Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel were sent to the government of the nation. They delivered God’s word to the king. The Gospels are about the Kingdom of Heaven. In Acts 9:15, Paul was commissioned by Christ to bear His name before kings. Revelation 5:10 reads, ..and we (Christians) shall reign on the earth. In fact, at least 71% of your Bible is about government. As previously mentioned, two sculptures of Moses are in our nation’s Capitol building. One is in the subway for all visitors to see. The other is on the north wall, in the chamber of the House of Moses wrote the first five books of the Bible. The Representatives. It is directly across from the Book of Deuteronomy is the fifth book. This course is Speaker’s seat. How about that! Christian art in a based on Moses’s fifth book. government building! The east-side of the U. S. Supreme Court building is Of all the men on earth, Moses was the most quali- decorated with an eighteen-foot high sculpture of fied to give instruction in government. Why? Moses holding the Ten Commandments. The govern- Because, in addition to experience in the govern- mental buildings and monuments of Washington ments of Egypt, Cush and Israel. -

Stockbridge Mohicans Past and Present

Mohicans Past & Present: a Study of Cultural Survival Lucianne Lavin, Ph.D. Mrs. Phoebe Ann Quinney A Scholar-in-Residence Project supported by Mass Humanities, state-based affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities February, 2011 Stockbridge Mohicans Past & Present: A Study of Cultural Survival Lucianne Lavin, Ph.D. Institute for American Indian Studies Washington, CT February, 2011 Abstract Study of artifacts collected from Stockbridge Mohicans living in Wisconsin between 1929 and 1937 and associated documents show that although they had been Christianized, victimized and precariously depopulated through European diseases, poverty and warfare over the past 300 years, the Mohicans remained a tribal community throughout the historical period. They achieved this through adherence to core cultural and spiritual traditions and strong leadership that focused tribal members on several key survival strategies, which allowed the Mohican people to remain together physically and politically. Their story is one of courage and persistence in the face of seemingly unbeatable odds. Introduction This paper is a result of my research during the summer/fall of 2010 as the Scholar in Residence at the Stockbridge Mission House in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. The program is funded by Mass Humanities, a state-based affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities, to advance ―the interpretation and presentation of history by Massachusetts history organizations‖.1 The goal of this particular project was to broaden our understanding of the