Federal Regulation of Air Transportation: Rates and Business Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recasting the Air Route Pattern by Airline Consolidations and Mergers Paul D

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Southern Methodist University Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 21 | Issue 3 Article 4 1954 Recasting the Air Route Pattern by Airline Consolidations and Mergers Paul D. Zook Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Paul D. Zook, Recasting the Air Route Pattern by Airline Consolidations and Mergers, 21 J. Air L. & Com. 293 (1954) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol21/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. RECASTING THE AIR ROUTE PATTERN BY AIRLINE CONSOLIDATIONS AND MERGERS By PAUL D. ZOOK Associate Professor of Business Administration, Southern Metho- dist University. B.A., 1934; Goshen College; M.A., 1940; Ph.D., 1954; University of Illinois. INTRODUCTION M EASURED by its past, civil air transportation has made great strides in providing safe, efficient and economic service in the United States. A study of the present, however, provides no grounds for complacency. It reveals the need for persistent efforts if the im- proved service possibilities of a technologically young industry are to be realized in a dynamic market. Current analysis also discloses heavy continued reliance on financial support by the public treasury for some parts of the civil air transport system. While public financial support is not necessarily undesirable, the present degree of depend- ence is viewed critically by transportation authorities and has become a matter of concern for the Civil Aeronautics Board. -

Air Travel Consumer Report

Air Travel Consumer Report A Product Of The OFFICE OF AVIATION CONSUMER PROTECTION Issued: June 2021 Flight Delays1 April 2021 Mishandled Baggage, Wheelchairs, and Scooters 1 April 2021 Oversales1 1st Quarter 2021 Consumer Complaints2 April 2021 (Includes Disability and Discrimination Complaints) Airline Animal Incident Reports4 April 2021 Customer Service Reports to the Dept. of Homeland Security3 April 2021 1 Data collected by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Website: http://www.bts.gov 2 Data compiled by the Office of Aviation Consumer Protection. Website: http://www.transportation.gov/airconsumer 3 Data provided by the Department of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Administration 4 Data collected by the Office of Aviation Consumer Protection TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page Section Page Introduction 3 Flight Delays (continued) Flight Delays Table 8 31 Explanation 4 List of Regularly Scheduled Domestic Flights Branded Codeshare Partners 5 with Tarmac Delays Over 3 Hours, By Marketing/Operating Carrier Table 1 6 Table 8A Overall Percentage of Reported Flight List of Regularly Scheduled International Flights with 32 Operations Arriving On-Time, by Reporting Marketing Carrier Tarmac Delays Over 4 Hours, By Marketing/Operating Carrier Table 1A 7 Appendix 33 Overall Percentage of Reported Flight Operations Arriving On-Time, by Reporting Operating Carrier Mishandled Baggage Table 1B 8 Explanation 34 Overall Percentage of Reported Flight Ranking- by Marketing Carrier (Monthly) 35 Operations Arriving On-Time, by Reporting Marketing -

Cred/F Union Assets Pass $5 Million Mark

Veteran TWA Captain Leads Double Life With Off-Duty Study SEE PAGE FIVE VOL. 18, NO. 33 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES WEEKLY EMPLOYEE PUBLICATION AUGUST 18, 1955 DORENE COX PETTY CLINGMAN SUE MORGAN TOMMIE MOFFETT ROBERTA SHOOK MARY LOU WEIHE TWA TWA BNF BNF CAL CAL TWA Applies For New Two TWA Girls Named for $80 Excursion Fares From Coast to Coast Cred/f Union Assets Queen Finals on TV Snow NEW YORK—The lowest trans continental air fare ever offered KANSAS CITY—Dorene Cox, typ ist clerk, and Betty Clingman, by a scheduled U. S. airline was Pass $5 Million Mark hostess, were selected Tuesday announced today by TWA in an night from among 38 contestants application filed with the Civil KANSAS CITY—E. Wiley Barker, president of the TWA Club Credit to represent TWA in the final Exceptions to Aeronautics board. Effective Sep Union, today announced that the assets of the Credit Union went over judging next week for queen of tember 12, upon approval by the the $5,000,000 mark as of July 31. In the past twelve months, the the third annual Airlines ball to CAB, the new "excursion" fare assets have increased $1,060,000. be held Oct. 1. will provide round-trip sky During the same period, deposits increased $1,013,000 and loans in Competing for the queen title CAB Examiner tourist service on regular sched creased $912,000. with the two TWA girls will be uled flights between New York Barker attributed the increase two candidates from each of the and Los Angeles or San Francisco in loans to the tremendous buying other airlines serving Kansas City. -

Air Travel Consumer Report

U.S. Department of Transportation Air Travel Consumer Report A Product Of The OFFICE OF AVIATION ENFORCEMENT AND PROCEEDINGS Aviation Consumer Protection Division Issued: August 2015 1 Flight Delays June 2015 1 Mishandled Baggage June 2015 January – June 2015 1 nd. Oversales 2 Quarter 2015 January – June 2015 2 Consumer Complaints June 2015 (Includes Disability and January – June 2015 Discrimination Complaints) Customer Service Reports to the Dept. of Homeland Security3 June 2015 4 Airline Animal Incident Reports June 2015 1 Data collected by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Website: http://www.bts.gov/ 2 Data compiled by the Aviation Consumer Protection Division. Website: http://www.dot.gov/airconsumer 3 Data provided by the Department of Homeland Security, Transportation Security Administration 4 Data collected by the Aviation Consumer Protection Division TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Section Page Page Flight Delays (continued) Introduction Table 11 27 2 List of Regularly Scheduled Flights with Tarmac Flight Delays Delays Over 3 Hours, By Carrier Explanation 3 Table 11A 28 Table 1 4 List of Regularly Scheduled International Flights with Overall Percentage of Reported Flight Tarmac Delays Over 4 Hours, By Carrier Operations Arriving On Time, by Carrier Table 12 29 Table 1A 5 Number and Percentage of Regularly Scheduled Flights Overall Percentage of Reported Flight With Tarmac Delays of 2 Hours or More, By Carrier Operations Arriving On Time and Carrier Rank, Footnotes 30 by Month, Quarter, and Data Base to Date Appendix 31 Table -

The Decade That Terrorists Attacked Not Only the United States on American Soil, but Pilots’ Careers and Livelihoods

The decade that terrorists attacked not only the United States on American soil, but pilots’ careers and livelihoods. To commemorate ALPA’s 80th anniversary, Air Line Pilot features the following special section, which illustrates the challenges, opportunities, and trends of one of the most turbulent decades in the industry’s history. By chronicling moments that forever changed the aviation industry and its pilots, this Decade in Review—while not all-encompassing—reflects on where the Association and the industry are today while reiterating that ALPA’s strength and resilience will serve its members and the profession well in the years to come. June/July 2011 Air Line Pilot 13 The Decade— By the Numbers by John Perkinson, Staff Writer lthough the start of the millennium began with optimism, 2001 and the decade that followed has been infamously called by some “The Lost Decade.” And statistics don’t lie. ALPA’s Economic A and Financial Analysis (E&FA) Department dissected, by the numbers, the last 10 years of the airline industry, putting together a compelling story of inflation, consolidation, and even growth. Putting It in Perspective During the last decade, the average cost of a dozen large Grade A eggs jumped from 91 cents to $1.66, an increase of 82.4 percent. Yet the Air Transport Association (ATA) reports that the average domestic round-trip ticket cost just $1.81 more in 2010 than at the turn of the decade—$316.27 as compared to $314.46 in 2001 (excluding taxes). That’s an increase of just 0.6 percent more. -

ISASI Forum. That Knowledge, and If You Possess That Tion and Planning Concepts

Air Safety Through Investigation OCTOBER-DECEMBER 2016 Journal of the International Society of Air Safety Investigators “JERRY LEDERER WAS LIKE A FATHER TO TOBY, WHO HAS SPENT A LIFETIME WORKING SELFLESSLY TO ENHANCE AVIATION SAFETY AND HAS DONE SO WITH THE UTMOST PROFESSIONALISM AND INTEGRITY. THERE IS NO ONE MORE DESERVING OF THIS PRESTIGIOUS JERRY LEDERER AWARD THAN TOBY.” —ISASI PRESIDENT FRANK DEL GANDIO ISASI 2016: Air Accident Investigators Examine Links to Safety Networks—page 5 Advancing Safety Through Multiple Means—page 11 ISASI Presents Eugene “Toby” Carroll Its 2016 Lederer Award—page 14 Another Way to Assess Turbofan Engine Operation During a Crash—page 16 Crash Scene Hazard Management: An Updated Approach—page 22 Five Receive ISASI Scholarships—page 24 CONTENTS Air Safety Through Investigation Journal of the International Society of Air Safety Investigators FEATURES Volume 49, Number 4 5 ISASI 2016: Air Accident Investigators Examine Links to Publisher Frank Del Gandio Safety Networks Editorial Advisor Richard B. Stone By J. Gary DiNunno, ISASI—Delegates to ISASI 2016 meet in Reykjavik, Iceland, on Editor Esperison Martinez October 18–20 for the Society’s annual international accident investigation and Design Editor Jesica Ferry prevention conference to listen to technical presentations and participate in Associate Editor Susan Fager discussions with the overall theme of “Every Link Is Important.” ISASI Forum (ISSN 1088-8128) is published quar- terly by the International Society of Air Safety 11 Advancing Safety Through Multiple Means Investigators. Opinions expressed by authors do By Kristi Dunks, Ph.D., Office of Aviation Safety, U.S. NTSB—After an aircraft ac- not necessarily represent official ISASI position cident occurs, safety issues are identified and safety recommendations are issued or policy. -

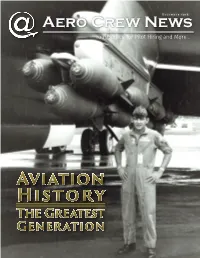

Your Source for Pilot Hiring and More

December 2018 Aero Crew News Your Source for Pilot Hiring and More... Aviation History The Greatest Generation ExpressJet is taking off with a new Pilot Contract Top-Tier Compensation and Work Rules $40/hour first-year pay $10,000 annual override for First Officers, $8,000 for Captains New-hire bonus 100% cancellation and deadhead pay $1.95/hour per-diem Generous 401(k) match Friendly commuter and reserve programs ARE YOU READY FOR EXPRESSJET? FLEET DOMICILES UNITED CPP 126 - Embraer ERJ145 Chicago • Cleveland Spend your ExpressJet career 20 - Bombardier CRJ200 Houston • Knoxville knowing United is in Newark your future with the United Pilot Career Path Program Apply today at expressjet.com/apply. Questions? [email protected] expressjet.com /ExpressJetPilotRecruiting @expressjetpilots Jump to each section Below contents by clicking on the title or photo. December 2018 16 28 22 36 26 Also Featuring: Letter from the Publisher 8 Aviator Bulletins 10 Stepping Back In Time 32 Remembering one from our nation’s “Greatest Generation” 4 | Aero Crew News BACK TO CONTENTS the grid New Airline Updated Flight Attendant Legacy Regional Alaska Airlines Air Wisconsin The Mainline Grid 48 American Airlines Cape Air Delta Air Lines Compass Airlines Legacy, Major, Cargo & International Airlines Hawaiian Airlines Corvus Airways United Airlines CommutAir General Information Endeavor Air Work Rules Envoy Additional Compensation Details Major ExpressJet Airlines Allegiant Air GoJet Airlines Airline Base Map Frontier Airlines Horizon Air JetBlue -

CRUCIAL TEST of CAB MERGER POLICY the Railman's Cry Bf "Merge Or Die" May Soon Become the Watchword of the Air Transport Industry

1962] NOTES THE AMERICAN-EASTERN APPLICATION: CRUCIAL TEST OF CAB MERGER POLICY The railman's cry bf "merge or die" may soon become the watchword of the air transport industry. Even though airlines are subject to detailed regulation-to implement safety as well as economic objectives-, including limitations on entry,' price regulation, and in certain cases, federal sub- sidy,2 competition is permitted "to the extent necessary" to ensure a healthy air transport system "adapted to the needs" of commerce, the postal serv- ice, and national defense.3 The United States maintains the world's only competitive airline system, and individual airlines are complaining not about regulation but about regulated competition. 4 In most major markets, there are at least two trunk airlines competing for supremacy and survival, and although the public has benefited from this competition in long-haul markets, service has deteriorated in shoit-haul and intermediate markets as long-haul equipment has become increasingly unsuited for short trips.5 Indeed, the advent of the jet age has set off an equipment race "unparalleled in any transportation system and unlikely to be duplicated." 6 Gains in net income have not kept pace with increases in gross traffic and revenue, and competition from other forms of transportation, particularly the auto- mobile, has become increasingly effective. 7 Because of the effects of the present degree of competition, the problems of equipment financing and low earnings, and the prospect that supersonic transport may magnify these difficulties, both the airlines ard the Civil Aetonautics Board have been considering merger as a possible solution.3 The most recent merger application-that of American and E~tei-n Aiifiesi the second and fourth largest air carriers in the United States- is in many ways unprecedented. -

Controlled Competition: Three Years of the Civil Aeronautics Act Neil G

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 12 | Issue 4 Article 2 1941 Controlled Competition: Three Years of the Civil Aeronautics Act Neil G. Melone Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Neil G. Melone, Controlled Competition: Three Years of the Civil Aeronautics Act, 12 J. Air L. & Com. 318 (1941) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol12/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. CONTROLLED COMPETITION: THREE YEARS OF THE CIVIL AERONAUTICS ACTt NEIL G. MELONE* INTRODUCTION The Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938 was an attempt to remedy a situation in the air transport industry which was characterized as "chaotic" by the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce.' From 1930 to 1934, the entire aviation industry had been dom- inated by three holding companies. 2 As a result of the so-called "spoils conferences" called by Postmaster General Brown in 1930, certain of these groups had secured the bulk of the government's airmail payments. Investigations by the Black Committee had re- vealed the alleged details of the "spoils conferences" and the extent of the interlocking relationships." On the basis of the testimony, Postmaster General Farley had cancelled the contracts in 1934 with- out notice or hearing.4 The experiment of mail flying by army pilots had proved disastrous, and remedy was sought in the Air Mail Act of 1934.5 Mail contracts were to be awarded after competitive bidding, and routes designated by the Postmaster General.6 The Act required the air transport companies to divorce themselves from manufactur- tAdapted from Thesis submitted to Professor Hart in Seminar on Federal Administration at Harvard Law School. -

Approval of Purchase Price in Sale of Airline

NOTES APPROVAL OF PURCHASE PRICE IN SALE OF AIRLINE PROPERTIES UNDER THE CIVIL AERONAUTICS ACT The Civil Aeronautics Board, in a recent decision approving the sale of an airlines route by one air carrier to another, has reaffirmed a policy which may have important effects on the future of economic airline regulation., Western Air Lines, a carrier operating primarily in the region west of the Rocky Moun- tains, had in recent years extended its activities eastward by the establishment of a route from Los Angeles to Denver and the acquisition of control of a sub- sidiary operating as far east as Minneapolis and St. Paul. The Denver-Los Angeles route proved profitable to Western in 1946 but, early in 1947, the com- pany found itself in serious financial difficulties in its other operations and it de- termined to abandon its transcontinental ambitions. The prospect of future profitable operation of the Denver-Los Angeles route by Western being extreme- ly poor,2 it was decided that the route should be sold. In March, 1947 an agree- ment was negotiated by which Western was to transfer its certificate of public convenience and necessity for the route to United Air Lines, along with the planes and other physical properties used by Western on the route. The pur- chase price agreed upon was $3,75o,ooo, although the equipment and other tangible items involved were valued at slightly over $2,000,000. As required by statute, the agreement was submitted to the Civil Aeronautics Board for ap- proval. The five members of the Board all agreed that it was in the public interest that Western be allowed to abandon its Denver-Los Angeles route and that the route be transferred to United, into whose system it logically fitted. -

Advisory Circular

U.S. Department Advisory of Transportation Federal Aviatlon Admlnlstration Circular Subject: FAA CERTIFICATED MAINTENANCE Date: 3 /6/g 7 AC No: 140-71 AGENCIES DIRECTORY Initiated by: AN-640 Change: 1. PURPOSE. This advisory circular (AC) transmits a consolidated directory of all certificated Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) repair stations and manufacturer’s maintenancefacilities. The repair stations and manufacturer’s maintenancefacilities were certificated as of January 2 1, 1997, under the authority of Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 145, and the directories are current as of January 21, 1997. 2. CANCELLATION. This AC cancelsAC 140-7H, FAA Certificated Maintenance Agencies Directory, dated July 24, 1995. 3. DESCRIPTION. Appendix 1 is a listing of repair stations and appendix 2 is a listing of manufacturer’s maintenancefacilities, their addresses,ratings, and codes. 4. RATING LEGENDS, CODES, AND EXPLANATIONS. a. FAA certificated repair station rating codesare describedin detail in part -l45, and are: (1) AF-Airframe l-composite construction, small aircraft 2-composite construction, large aircraft 3-all metal construction, small aircraft 4-all metal construction, large aircraft (2) PP-Powerplant l--reciprocating engines,400 hp or less 2-reciprocating engines,more than 400 hp 3-turbine engines (3) PRP-Propeller l--fixed pitch and ground adjustablepropellers - wood, metal, or composite 2-all other propellers, by make (4) RAD-Radio l-communication equipment 2-navigation equipment 3-radar equipment AC 140-71 316197 (5) INS-Instrument l-mechanical 2--electrical 3-gyroscopic 44-electronic (6) AAC-Accessory l-mechanical 2--electrical 3-electronic (7) L--Limited AAC --accessories AF --airframe EE -emergency equipment FAB -aircraft fabric FL0 -floats INS -instruments LG -landing gear NDT -nondestructive testing OT --other PP -powerplant PRP -propellers RAD -radio equipment RB --rotor blades SS ---specialized (8) Ratings may be limited to a specific model of aircraft, powerplant, propeller, radio, instrument, accessory,or parts thereof. -

Air Transport

National Air & Space Museum Technical Reference Files: Air Transport NASM Staff 2017 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 2 Series F0: Air Transport, General............................................................................ 2 Series F1: Air Transport, Airlines........................................................................... 23 Series F2: Air Transport, by Region or Nation..................................................... 182 Series F3: Air Transport, Airports, General.......................................................... 189 Series F4: Air Transport, Airports, USA............................................................... 198 Series F5: Air Transport, Airports, Foreign.......................................................... 236 Series F6: Air Transport, Air Mail......................................................................... 251 National Air & Space Museum Technical Reference Files: Air Transport NASM.XXXX.1183.F Collection Overview Repository: National Air and Space Museum Archives Title: National