ON AQUINAS on EVIL* Abstract Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Problem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The rP oblem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions Edward Matusek University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Matusek, Edward, "The rP oblem of Evil in Augustine's Confessions" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3733 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Problem of Evil in Augustine’s Confessions by Edward A. Matusek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Thomas Williams, Ph.D. Roger Ariew, Ph.D. Joanne Waugh, Ph.D. Charles B. Guignon, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 14, 2011 Keywords: theodicy, privation, metaphysical evil, Manichaeism, Neo-Platonism Copyright © 2011, Edward A. Matusek i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iii Chapter One: Introduction to Augustine’s Confessions and the Present Study 1 Purpose and Background of the Study 2 Literary and Historical Considerations of Confessions 4 Relevance of the Study for Various -

Origen of Alexandria and St. Maximus the Confessor: an Analysis and Critical Evaluation of Their Eschatological Doctrines

Origen of Alexandria and St. Maximus the Confessor: An Analysis and Critical Evaluation of Their Eschatological Doctrines by Edward Moore ISBN: 1-58112-261-6 DISSERTATION.COM Boca Raton, Florida USA • 2005 Origen of Alexandria and St. Maximus the Confessor: An Analysis and Critical Evaluation of Their Eschatological Doctrines Copyright © 2004 Edward Moore All rights reserved. Dissertation.com Boca Raton, Florida USA • 2005 ISBN: 1-58112-261-6 Origen of Alexandria and St. Maximus the Confessor: An Analysis and Critical Evaluation of Their Eschatological Doctrines By Edward Moore, S.T.L., Ph.D. Table of Contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................VI ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................VII PREFACE.....................................................................................................................VIII INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 ORIGEN, MAXIMUS, AND THE IMPORTANCE OF ESCHATOLOGY ....................................... 1 THE HISTORY AND IMPORTANCE OF ESCHATOLOGY IN CHRISTIAN THOUGHT – SOME BRIEF REMARKS. ............................................................................................................. 3 CHAPTER 1: ORIGEN’S INTELLECTUAL BACKGROUND................................... 15 BRIEF BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH...................................................................................... -

Periphyseon' Jonathan Mounts

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 2011 Salvation of the Damned Within the 'Periphyseon' Jonathan Mounts Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Mounts, J. (2011). Salvation of the Damned Within the 'Periphyseon' (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/956 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SALVATION OF THE DAMNED WITHIN THE PERIPHYSEON A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Jonathan G. Mounts April 2011 Copyright by Jonathan G. Mounts 2011 THE SALVATION OF THE DAMNED WITHIN THE PERIPHYSEON By Jonathan G. Mounts Approved April 1, 2011 ________________________ ________________________ L. Michael Harrington, Ph.D Thérèse Bonin, Ph.D Associate Professor of Philosophy Associate Professor of Philosophy Director Committee Member ________________________ ________________________ James Swindal, Ph.D James Swindall, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Philosophy Associate Professor of Philosophy Committee Member Department Chair ________________________ Christopher Duncan, Ph.D. Dean, The McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts iii ABSTRACT THE SALVATION OF THE DAMNED WITHIN THE PERIPHYSEON By Jonathan G. Mounts May 2011 Dissertation supervised by L. Michael Harrington, Ph.D This dissertation shall examine the claim of John Scottus Eriugena, the ninth century Irish philosopher, that all things must ultimately return to unity with their creator. -

These Disks Contain My Version of Paul Spade's Expository Text and His Translated Texts

These disks contain my version of Paul Spade's expository text and his translated texts. They were converted from WordStar disk format to WordPerfect 5.1 disk format, and then I used a bunch of macros and some hands-on work to change most of the FancyFont formatting codes into WordPerfect codes. Many transferred nicely. Some of them are still in the text (anything beginning with a backslash is a FancyFont code). Some I just erased without knowing what they were for. All of the files were cleaned up with one macro, and some of them have been further doctored with additional macros I wrote later and additional hand editing. This explains why some are quite neat, and others somewhat cluttered. In some cases I changed Spade's formatting to make the printout look better (to me); often this is because I lost some of his original formatting. I have occasionally corrected obvious typos, and in at least one case I changed an `although' to a `but' so that the line would fit on the same page. With these exceptions, I haven't intentionally changed any of the text. All of the charts made by graphics are missing entirely (though in a few cases I perserved fragments so you can sort of tell what it was like). Some of the translations had numbers down the side of the page to indicate location in the original text; these are all lost. Translation 1.5 (Aristotle) was not on the disk I got, so it is listed in the table of contents, but you won't find it. -

Psychological Arguments for Free Will DISSERTATION Presented In

Psychological Arguments for Free Will DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew Kissel Graduate Program in Philosophy The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Richard Samuels, Advisor Declan Smithies Abraham Roth Copyrighted by Andrew Kissel 2017 Abstract It is a widespread platitude among many philosophers that, regardless of whether we actually have free will, it certainly appears to us that we are free. Among libertarian philosophers, this platitude is sometimes deployed in the context of psychological arguments for free will. These arguments are united under the idea that widespread claims of the form, “It appears to me that I am free,” on some understanding of appears, justify thinking that we are probably free in the libertarian sense. According to these kinds of arguments, the existence of free will is supposed to, in some sense, “fall out” of widely accessible psychological states. While there is a long history of thinking that widespread psychological states support libertarianism, the arguments are often lurking in the background rather than presented at face value. This dissertation consists of three free-standing papers, each of which is motivated by taking seriously psychological arguments for free will. The dissertation opens with an introduction that presents a framework for mapping extant psychological arguments for free will. In the first paper, I argue that psychological arguments relying on widespread belief in free will, combined with doxastic conservative principles, are likely to fail. In the second paper, I argue that psychological arguments involving an inference to the best explanation of widespread appearances of freedom put pressure on non-libertarians to provide an adequate alternative explanation. -

Rock of Atheism’

Navigating around Hume’s ‘Rock of Atheism’ by Mike Tonks, Second Master, Shrewsbury School Published in ‘Dialogue: A journal of religion and philosophy’, issue 49, November 2017 _______________________________________________________________________________ Before starting work this morning I decided to check the BBC website to see what the main news headlines were. Exploring further I found myself confronted by numerous illustrations of what ‘philosophers of religion’ might call ‘The Problem of Evil.’ The inescapable truth is that the human condition is punctuated by suffering. At least twenty people had been killed in a bomb attack in Bangkok. The refugee crisis continued in many areas of Europe including France, Italy and Macedonia. Another headline reported the establishment of a new enquiry into child abuse in the Roman Catholic Church of Scotland. A tornado had struck the southern coast of Mexico, fires blazed out of control on the Idaho / Oregon border and a state of emergency had been declared in Ecuador due to growing activity in the Cotopaxi volcano. Reading these and many other similar accounts a question presents itself – ‘Are such events necessary and inevitable?’ Can one imagine a world without such brutality, pain and torment? And perhaps most challenging of all, does this world present itself as the creative work of a supremely perfect, powerful and benevolent personal deity who enjoys a loving relationship with all of his creation? Welcome to the study of what ‘philosophers of religion’ refer to as The Problem of Evil! There is an enormous amount of material available on this topic and therefore part of the challenge at ‘A’ Level lies in establishing a structured approach to your investigations. -

On Pain and the Privation Theory of Evil

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PhilPapers ON PAIN AND THE PRIVATION THEORY OF EVIL IRIT SAMET King’s College London Abstract. The paper argues that pain is not a good counter-example to the privation theory of evil. Objectors to the privation thesis see pain as too real to be accounted for in privative terms. However, the properties for which pain is intuitively thought of as real, i.e. its localised nature, intensity, and quality (prickly, throbbing, etc.) are features of the senso-somatic aspect of pain. This is a problem for the objectors because, as findings of modern science clearly demonstrate, the senso-somatic aspect of pain is neurologically and clinically separate from the emotional-psychological aspect of suffering. The intuition that what seems so real in pain is also the source of pain’s negative value thus falls apart. As far as the affective aspect of pain, i.e. ‘painfulness’ is concerned, it cannot refute the privation thesis either. For even if this is indeed the source of pain’s badness, the affective aspect is best accounted for in privative terms of loss and negation. The same holds for the effect of pain on the aching person. INTRODUCTION ‘Just as there is no target set up for misses, so there is no nature of evil in the universe either’. (Epictetus, Encheiridion 27) Philosophers since Plato have been making a striking claim about evil: evil, they said, is essentially devoid of being, an absence of good. This seemingly absurd statement became the standard conclusion of rationalistic investigations into the ontology of evil. -

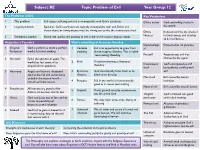

Problem of Evil Year Group: 12

Subject: RE Topic: Problem of Evil Year Group: 12 The Problems of Evil Key Vocabulary 1 The problem Evil causes suffering and evil is incompatible with God’s attributes. Divine action God controlling events in 2 Logical problem Epicurus: God’s attributes are logically incompatible with evil. Either evil, the world benevolence or omnipotence must be wrong to resolve the inconsistent triad Divine Irenaeus said we are created likeness in God’s image and develop 3 Evidential problem Rowe: the quality and quantity of evil in the world causes religious doubt. to be his likeness Augustine’s Theodicy Hick’s reworking of Irenaean theodicy Dysteleologic Existence has no purpose 1 Original God is perfect so made a perfect 1 Irenaean Evil is an opportunity to grow from al Perfection world. It lacked nothing theodicy divine image to likeness. This is called ‘soul-making’ theodicy Freewill Autonomous and free 2 Privation Evil is the absence of good. The choices by the agent world has lost some of its 2 Hick Modern reworking of Irenaeus’ Inconsistent God’s omnipotence and original divine goodness theodicy triad benevolence conflict with 3 Harmony Angels and humans disobeyed 3 Epistemic God intentionally hides from us to evil God at the Fall and so harmony distance allow us to develop ended in the natural world – Moral evil Evil caused by human natural evil now occurs 4 Purpose Evil in the world is instrumentally intention good as it causes soul-making Natural evil Evil caused by natural events 4 Punishment All humans are punished for 5 Freewill Moral growth must be autonomous, Adam’s sin because God is just not forced by God Original God’s creation was good 5 Grace God sent Jesus out of love and to perfection and lacked nothing create to possibility of 6 Virtues We only learn virtues like charity in forgiveness and salvation suffering Privatio boni Absence of goodness (privation) 6 Freewill God had to give us freewill as it 7 Universal We all suffer and so are all saved and is more loving, despite the evil salvation go to heaven. -

The Problem of Evil

3 The Problem of Evil For what is that which we call evil but the absence of good?1 espite being conceived in secular terms in much contemporary Dthought, the “problem of evil” has traditionally been a theological one concerned with the question of how to reconcile the existence of suf- fering, and hence evil, in the world, with the characterization of the Judeo-Christian God as benevolent, omniscient, and omnipotent. Formally articulated by Epicurus (341–270 BCE) and originally quoted in the work of Lactantius (c. 260–340 CE), the “problem of evil” is tradi- tionally presented as follows: God either wishes to take away evils, and is unable; or He is able, and is unwilling; or He is neither willing nor able, or He is both willing and able. If He is willing and is unable, He is feeble, which is not in accordance with the character of God; if He is able and willing, He is envious, which is equally at variance with God; if He is neither willing nor able, He is both envious and feeble and, therefore not God; if He is both willing and able, which alone is suitable to God, from what source then are evils? Or why does He not remove them?2 Presented syllogistically, the problem is this: God is benevolent. God is omnipotent (which should be taken to include omniscience). There is evil in the world. If the first two propositions are true, the third cannot be. R. Jeffery, Evil and International Relations © Renée Jeffery 2008 34 EVIL AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Now the third is true as a matter of observable fact. -

The Evidential Problem of Evil

To put it simply The Problem of Evil topic but simplified and sometimes a bit chattier than it should be. The Specification The problem of evil • The concept of evil (natural and moral) and the logical and evidential problem of evil • Religious responses to the problem of evil. Credit will be given for relevant knowledge of any theodicy, but candidates are expected to be familiar with the following: – The main themes of theodicies in the Augustinian tradition – The free will defence – John Hick’s ‘vale of soul making’ theodicy (from the Irenaean tradition) – Responses to evil in process thought Issues arising • The success of the theodicies as a response to the problem of evil • What poses the greatest challenge to faith in God – natural evil or moral evil? • Is free will a satisfactory explanation for the existence of evil in a world created by God? • The strengths and weaknesses of these responses to the problem of evil The concept of evil (natural and moral) and the logical and evidential problem of evil Natural (or non-moral) evil refers to evils caused by the natural state of things i.e. they are nothing to do with human intentions and choices. They are evils brought about by the laws of nature and the state of the world. We would include natural disasters and death under this definition. Moral evil refers to evils that have come about as a direct result of human intentions and choices. These are evils that simply wouldn’t have occurred if it hadn’t have been for humans. -

Neoplatonism, Then And

NEOPLATONISM, THEN AND NOW Date: 2-11-2014 OPENING WORDS Earlier this year, I undertook a twelve-week philosophy course at Sydney Community College, in Rozelle. It was a fairly easy- going, yet exhaustive course that saw us cover everything from the pre-Socratic philosophers of ancient Greece, right up to the musings of Jürgen Habermas in the twentieth century. We covered Descartes and Spinoza, Hegel and the Hindus, amongst others – the span of time we examined stretched over more than 2,500 years. Not at all bad for a course that only lasted three months. Needless to say, I found a lot to think about in this time, and in the months since – not least of all, which philosophical traditions I find myself most agreeing with. In the months since the course concluded, I have worked out that I am much more a rationalist than an empiricist, certainly much more a virtue ethicist than a consequentialist, and almost certainly a monist, rather than a dualist (that is to say, in a metaphysical sense, I find myself agreeing more with Spinoza than Descartes, and notably more with Hinduism than Christianity in its view of God and the universe). Though, I must admit, I’m still not certain whether my own personal philosophy fits in more with the analytic or continental tradition – I’ll have to work that one out. Seriously, though, I find philosophy fascinating – it is, after all, the study of and attempt to make sense of the general and fundamental problems of all existence, problems that every human being (provided they’re bothered to think about it) has grappled with since time immemorial, and continues to do so today. -

I. Richard Swinburne's Theism

UNIVERSITY OF NAVARRA ECCLESIASTICAL FACULTY OF PHILOSOPHY Alex Mbonimpa The Providence of God according to Richard Swinburne: A Critical Study under the Guidance of St. Thomas Aquinas. Thesis for a Doctorate supervised by Prof. Dr. Rev. Enrique Moros Pamplona 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ................................................................ 11 Method.............................................................................. 15 Biographical Note............................................................. 19 Acknowledgements .......................................................... 24 I. RICHARD SWINBURNE’S THEISM ............................ 27 1. Justification and Knowledge ............................................ 29 1.1 Subjective Justification ............................................. 30 1.2 Objective Justification .............................................. 32 1.3 The Quest for an Ultimate Explanation .................... 35 a) How Explanation Works ........................................ 37 b) The Truth of an Explanation .................................. 41 c) Candidates for an Ultimate Explanation ................ 46 1.4 The Justification of Theism ...................................... 47 a) The Simplicity of Theism....................................... 47 b) The Limit of Scientific Explanation ....................... 50 2. The Attributes of God....................................................... 53 2.1 What Swinburne