The Failure of a Clerical Proto-State: Hazarajat, 1979 - 1984

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

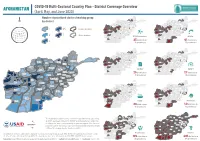

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

Watershed Atlas Part IV

PART IV 99 DESCRIPTION PART IV OF WATERSHEDS I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED II. AMU DARYA RIVER BASIN III. NORTHERN RIVER BASIN IV. HARIROD-MURGHAB RIVER BASIN V. HILMAND RIVER BASIN VI. KABUL (INDUS) RIVER BASIN VII. NON-DRAINAGE AREAS PICTURE 84 Aerial view of Panjshir Valley in Spring 2003. Parwan, 25 March 2003 100 I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED Part IV of the Watershed Atlas describes the 41 watersheds Graphs 21-32 illustrate the main characteristics on area, popu- defined in Afghanistan, which includes five non-drainage areas lation and landcover of each watershed. Graph 21 shows that (Map 10 and 11). For each watershed, statistics on landcover the Upper Hilmand is the largest watershed in Afghanistan, are presented. These statistics were calculated based on the covering 46,882 sq. km, while the smallest watershed is the FAO 1990/93 landcover maps (Shapefiles), using Arc-View 3.2 Dasht-i Nawur, which covers 1,618 sq. km. Graph 22 shows that software. Graphs on monthly average river discharge curve the largest number of settlements is found in the Upper (long-term average and 1978) are also presented. The data Hilmand watershed. However, Graph 23 shows that the largest source for the hydrological graph is the Hydrological Year Books number of people is found in the Kabul, Sardih wa Ghazni, of the Government of Afghanistan – Ministry of Irrigation, Ghorband wa Panjshir (Shomali plain) and Balkhab watersheds. Water Resources and Environment (MIWRE). The data have Graph 24 shows that the highest population density by far is in been entered by Asian Development Bank and kindly made Kabul watershed, with 276 inhabitants/sq. -

Refugees Refugees Unreached & Unengaged People Groups Living in Hamburg, Germany Unreached & Unengaged People Groups Living in Hamburg, Germany

Refugees Refugees Unreached & Unengaged People Groups living in Hamburg, Germany Unreached & Unengaged People Groups living in Hamburg, Germany Refugees in Hamburg, Gemany Languages in Camp Refugees in Hamburg, Gemany Languages in Camp Unrest in the Middle East has Unrest in the Middle East has brought a flood of refugees to Farsi brought a flood of refugees to Farsi Europe. Europe. Hamburg Hamburg Germany has taken in Kurdish Germany has taken in Kurdish over1million refugees in Germany over1million refugees in Germany the past two years. German the past two years. German There are 200 camps in There are 200 camps in Hamburg where about 100,000 refugees reside. English Hamburg where about 100,000 refugees reside. English These refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Eritrea, These refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Eritrea, Albania and other locations have proven to be a Italian Albania and other locations have proven to be a Italian fertile harvest field. fertile harvest field. Population Religion Shared Experience Population Religion Shared Experience Refugee People Groups In the context of a Refugee People Groups In the context of a living in Hamburg include: Islam 99% refugee camp, refugees living in Hamburg include: Islam 99% refugee camp, refugees Iran – Persians, Azer- become a people group. Iran – Persians, Azer- become a people group. baijanis, Armenians, They end up having baijanis, Armenians, They end up having Other <1% Other <1% Turkmen, Afghans and an affinity due to their Turkmen, Afghans and an affinity due to their Sorani Kurds. shared experience. Sorani Kurds. shared experience. Afghanistan – Tajiks, Christian <1% As long as they have Afghanistan – Tajiks, Christian <1% As long as they have Pashtuns, Hazaras, some sort of ability to Pashtuns, Hazaras, some sort of ability to Uzbeks and Balochs. -

Hazara Tribe Next Slide Click Dark Blue Boxes to Advance to the Respective Tribe Or Clan

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Advance to Hazara Tribe next slide Click dark blue boxes to advance to the respective tribe or clan. Hazara Abak / Abaka Besud / Behsud / Basuti Allakah Bolgor Allaudin Bubak Bacha Shadi Chagai Baighazi Chahar Dasta / Urni Baiya / Baiyah Chula Kur Barat Dahla / Dai La Barbari Dai Barka Begal Dai Chopo Beguji / Bai Guji Dai Dehqo / Dehqan Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec. Vol 6; Hazaras Poladi, 37; EE Bacon, P.20-31 Topography, Ethnology, Resources & History of Afghanistan. Part II. Calcutta:, 1871 (p. 628). Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Return to Advance to First slide Hazara Tribe next slide Hazara Dai Kundi / Deh Kundi Dayah Dai Mardah / Dahmarda Dayu Dai Mirak Deh Zengi Dai Mirkasha Di Meri / Dai Meri Dai Qozi Di Mirlas / Dai Mirlas Dai Zangi / Deh Zangi Di Nuri / Dai Nuri Daltamur Dinyari /Dinyar Damarda Dosti Darghun Faoladi Dastam Gadi / Gadai Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec. Vol 6; Hazaras Poladi, 37; EE Bacon, P.20-31 Topography, Ethnology, Resources & History of Afghanistan. Part II. Calcutta:, 1871 (p. 628). Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Return to Advance to First slide Hazara Tribe next slide Hazara Gangsu Jaokar Garhi Kadelan Gavi / Gawi Kaghai Ghaznichi Kala Gudar Kala Nao Habash Kalak Hasht Khwaja Kalanzai Ihsanbaka Kalta Jaghatu Kamarda Jaghuri / Jaghori Kara Mali Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). -

Assessing the Circumstances and Needs of Refugee Communities

HELPING STRANGERS BECOME NEIGHBOURS Assessing The Circumstances And Needs Of Refugee Communities In Derby Upbeat Communities Overdale House 96 Whitaker Road Derby, DE23 6AP [email protected] 01332 916150 www.upbeatcommunities.org CONTENTS Welcome 4 Executive Summary 5 Assessing The Circumstances And Needs Of 6 Refugee Communities In Derby Research Methodology 8 Community Snapshots 10 Eritrean Community 11 Iranian Community 11 Pakistani Community 13 Iraq – Kurdish Community 14 Albanian Community 15 Syrian Community 15 Sri Lanka – Tamil Community 16 Afghanistan – Hazara Community 16 Chinese Community 17 Themes Arising From The Cross-Section 19 Of Communities Stages Of Development Of Refugee Communities 20 Choosing To Stay In Derby Or Not? 21 English Language Provision 22 Refugee Mental Health 24 The Path To Work 25 Concern For The Next Generation 27 Patterns Of Community Engagement 28 Community Organisation And Voice 29 Conclusions And Recommendations 30 Conclusion / Recommendation 31 Appendix 1 33 Communities With Established Organisations 34 Appendix 2 35 New Communities Research 36 Questionnaire 1 – Individuals Appendix 3 39 New Communities Research 40 Questionnaire 2 – Focus Groups Acknowledgements 43 Abbreviations 43 As well as a providing a unique window into each of these communities – their WELCOME hopes, aspirations and concerns – common themes are drawn together which point to Upbeat Communities’ mission specific interventions which would greatly is ‘to help strangers become aid integration. The outcome of this will be neighbours’. We recognise that that refugees choose to stay in the city, becoming, as stated in our conclusion; engaging communities is key to that mission - both the refugee “powerful assets to the City of Derby, communities arriving in the city providing productive labour, generating and the settled community that new jobs and contributing across all areas of society”. -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Afghanistan Ghazni Province Land Cover

W # AFGHANISTAN E C Sar-e K har Dew#lak A N # GHAZNI PROVINCE Qarah Qowl( 1) I Qarkh Kamarak # # # # # Regak # # Gowshak # # # Qarah Qowl( 2) R V Qada # # # # # # Bandsang # # Dopushta Panqash # # # # # # # Qashkoh Kholaqol # LAND COVER MAP # Faqir an O # Sang Qowl Rahim Dad # # Diktur (1) # Owr Mordah Dahane Barikak D # Barigah # # # Sare Jiska # Baday # # Kheyr Khaneh # Uchak # R # Jandad # # # # # # # # # # Shakhalkhar Zardargin Bumak # # Takhuni # # # # # # # Karez Nazar # Ambolagh # # # # # # Barikak # # Hesar # # # # # Yarum # # # A P # # # # # # Kataqal'a Kormurda # # # # Qeshlaqha Riga Jusha Tar Bulagh # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # Ahangari # # Kuz Foladay # Minqol # # # Syahreg (2) # # # Maqa # Sanginak # # Baghalak # # # # # # # # # Sangband # Orka B aba # Godowl # Nayak # # # Gadagak # # # # Kota Khwab Altan # # Bahram # # # Katar # # # Barik # Qafak # Qargatak # # # # # # Garmak (3) # # # # # # # # # # Ternawa # # # Kadul # # # # Ghwach # K # # Ata # # # Dandab # # # # # Qole Khugan Sewak (2) Sorkh Dival # # # # # # # # Qabzar (2) # # Bandali # Ajar # Shebar # Hajegak # Sawzsang Podina N ## # # Churka # Nala # # # # # # # Qabzar-1 Turgha # Tughni # Warzang Sultani # # # # # # # # # # # # # Ramzi Qureh Now Juy Negah # # # # # # # # Shew Qowl # Syahsangak A # # # # # # # O # Diktur (2) # Kajak # # Mar Bolagh R V # Ajeda # Gola Karizak # # # Navor Sham # # Dahane Yakhshi Kolukh P # # # # AIMS Y Tanakhak Qal'a-i Dasht I Qole Aymad # Kotal Olsenak Mianah Bed # # # # N Tarbolagh Mar qolak Minqolak Sare Bed Sare Kor ya Ta`ina -

Afghanistan: Floods

P a g e | 1 Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Afghanistan: Floods DREF Operation n° MDRAF008 Glide n°: FL-2021-000050-AFG Expected timeframe: 6 months For DREF; Date of issue: 16/05/2021 Expected end date: 30/11/2021 Category allocated to the disaster or crisis: Yellow EPoA Appeal / One International Appeal Funding Requirements: - DREF allocated: CHF 497,700 Total number of people affected: 30,800 (4,400 Number of people to be 14,000 (2,000 households) assisted: households) 6 provinces (Bamyan, Provinces affected: 16 provinces1 Provinces targeted: Herat, Panjshir, Sar-i-Pul, Takhar, Wardak) Host National Society(ies) presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): Afghan Red Crescent Society (ARCS) has around 2,027 staff and 30,000 volunteers, 34 provincial branches and seven regional offices all over the country. There will be four regional Offices and six provincial branches involved in this operation. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: ARCS is working with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) and International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) with presence in Afghanistan. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: (i) Government ministries and agencies, Afghan National Disaster Management Authority (ANDMA), Provincial Disaster Management Committees (PDMCs), Department of Refugees and Repatriation, and Department for Rural Rehabilitation and Development. (ii) UN agencies; OCHA, UNICEF, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Organization for Migration (IOM) and World Food Programme (WFP). (iii) International NGOs: some of the international NGOs, which have been active in the affected areas are including, Danish Committee for Aid to Afghan Refugees (DACAAR), Danish Refugee Council (DRC), International Rescue Committee, and Care International. -

LAND RELATIONS in BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 Village Case Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Case Studies Series LAND RELATIONS IN BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 village case study Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit By Liz Alden Wily February 2004 Funding for this study was provided by the European Commission, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and the governments of Sweden and Switzerland. © 2004 The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU). All rights reserved. This case study report was prepared by an independent consultant. The views and opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of AREU. About the Author Liz Alden Wily is an independent political economist specialising in rural property issues and in the promotion of common property rights and devolved systems for land administration in particular. She gained her PhD in the political economy of land tenure in 1988 from the University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. Since the 1970s, she has worked for ten third world governments, variously providing research, project design, implementation and policy guidance. Dr. Alden Wily has been closely involved in recent years in the strategic and legal reform of land and forest administration in a number of African states. In 2002 the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit invited Dr. Alden Wily to examine land ownership problems in Afghanistan, and she continues to return to follow up on particular concerns. About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research organisation that conducts and facilitates action-oriented research and learning that informs and influences policy and practice. -

LAND RELATIONS in BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 Village Case Study

Case Studies Series LAND RELATIONS IN BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 village case study Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit By Liz Alden Wily February 2004 Funding for this study was provided by the European Commission, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and the governments of Sweden and Switzerland. © 2004 The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU). All rights reserved. This case study report was prepared by an independent consultant. The views and opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of AREU. About the Author Liz Alden Wily is an independent political economist specialising in rural property issues and in the promotion of common property rights and devolved systems for land administration in particular. She gained her PhD in the political economy of land tenure in 1988 from the University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. Since the 1970s, she has worked for ten third world governments, variously providing research, project design, implementation and policy guidance. Dr. Alden Wily has been closely involved in recent years in the strategic and legal reform of land and forest administration in a number of African states. In 2002 the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit invited Dr. Alden Wily to examine land ownership problems in Afghanistan, and she continues to return to follow up on particular concerns. About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research organisation that conducts and facilitates action-oriented research and learning that informs and influences policy and practice. AREU also actively promotes a culture of research and learning by strengthening analytical capacity in Afghanistan and by creating opportunities for analysis, thought and debate. -

Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Urban Studies Senior Seminar Papers Urban Studies Program 11-2009 Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan Benjamin Dubow University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/senior_seminar Dubow, Benjamin, "Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan" (2009). Urban Studies Senior Seminar Papers. 13. https://repository.upenn.edu/senior_seminar/13 Suggested Citation: Benjamin Dubow. "Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan." University of Pennsylvania, Urban Studies Program. 2009. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/senior_seminar/13 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ethnicity, Space, and Politics in Afghanistan Abstract The 2004 election was a disaster. For all the unity that could have come from 2001, the election results shattered any hope that the country had overcome its fractures. The winner needed to find a way to unite a country that could not be more divided. In Afghanistan’s Panjshir Province, runner-up Yunis Qanooni received 95.0% of the vote. In Paktia Province, incumbent Hamid Karzai received 95.9%. Those were only two of the seven provinces where more than 90% or more of the vote went to a single candidate. Two minor candidates who received less than a tenth of the total won 83% and 78% of the vote in their home provinces. For comparison, the most lopsided state in the 2004 United States was Wyoming, with 69% of the vote going to Bush. This means Wyoming voters were 1.8 times as likely to vote for Bush as were Massachusetts voters. Paktia voters were 120 times as likely to vote for Karzai as were Panjshir voters.