Crystalloid Coloading Vs. Colloid Coloading in Elective Caesarean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparison of Norepinephrine and Cafedrine/Theodrenaline Regimens for Maintaining Maternal Blood Pressure During

IBIMA Publishing Obstetrics & Gynecology: An International Journal http://www.ibimapublishing.com/journals/GYNE/gyne.html Vol. 2015 (2015), Article ID 714966, 12 pages DOI: 10.5171/2015.714966 Research Article Comparison of Norepinephrine and Cafedrine/Theodrenaline Regimens for Maintaining Maternal Blood Pressure during Spinal Anaesthesia for Caesarean Section Hoyme, M.1, Scheungraber, C.2, Reinhart, K.3 and Schummer, W.3 1Department of Internal Medicine I (Cardiology, Angiology, Pneumology) Friedrich Schiller University, Jena, Germany 2Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Friedrich Schiller University, Jena, Germany 3Clinic of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, Friedrich Schiller University, Jena, Germany Correspondence should be addressed to: Schummer, W.; [email protected] Received date: 9 January 2014; Accepted date: 4 April 2014; Published date: 26 August 2015 Academic Editor: Dan Benhamou Copyright © 2015. Hoyme, M., Scheungraber, C., Reinhart, K. and Schummer, W. Distributed under Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 Abstract Common phenomena of spinal anaesthesia for caesarean sections are hypotension and cardiovascular depression, both of which require immediate action. Akrinor® (theodrenaline and cafedrine), a sympathomimetic agent commonly used in Germany for such cases, was phased out with little notice at the end of 2005. Phenylephrine was not and is not an approved drug. Norepinephrine became the first-line drug. The outcome in neonates delivered by elective caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia was studied. At our university hospital, all elective caesarean sections under spinal anaesthesia from 2005 and 2006 were analysed regarding hypotension and the vasopressor administered. If maternal arterial pressure decreased by more than 20% of baseline, patients in 2005 received Akrinor®; patients in 2006 received norepinephrine. -

Hypotension After Spinal Anesthesia for Cesarean

REVIEW CURRENT OPINION Hypotension after spinal anesthesia for cesarean section: how to approach the iatrogenic sympathectomy Christina Massotha, Lisa To¨pelb, and Manuel Wenkb Purpose of review Hypotension during cesarean section remains a frequent complication of spinal anesthesia and is associated with adverse maternal and fetal events. Recent findings Despite ongoing research, no single measure for sufficient treatment of spinal-induced hypotension was 05/25/2020 on BhDMf5ePHKbH4TTImqenVDezntqwKeJGjCYTUOBBz0EyVSh+WquM7uJo3U//pWTO by http://journals.lww.com/co-anesthesiology from Downloaded Downloaded identified so far. Current literature discusses the efficacy of low-dose spinal anesthesia, timing and solutions for adequate fluid therapy and various vasopressor regimens. Present guidelines favor the use of from phenylephrine over ephedrine because of decreased umbilical cord pH values, while norepinephrine is http://journals.lww.com/co-anesthesiology discussed as a probable superior alternative with regard to maternal bradycardia, although supporting data is limited. Alternative pharmacological approaches, such as 5HT3-receptor antagonists and physical methods may be taken into consideration to further improve hemodynamic stability. Summary Current evidence favors a combined approach of low-dose spinal anesthesia, adequate fluid therapy and vasopressor support to address maternal spinal-induced hypotension. As none of the available vasopressors by is associated with relevantly impaired maternal and fetal outcomes, none of them should -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 De Juan Et Al

US 200601 10428A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2006/0110428A1 de Juan et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 25, 2006 (54) METHODS AND DEVICES FOR THE Publication Classification TREATMENT OF OCULAR CONDITIONS (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Eugene de Juan, LaCanada, CA (US); A6F 2/00 (2006.01) Signe E. Varner, Los Angeles, CA (52) U.S. Cl. .............................................................. 424/427 (US); Laurie R. Lawin, New Brighton, MN (US) (57) ABSTRACT Correspondence Address: Featured is a method for instilling one or more bioactive SCOTT PRIBNOW agents into ocular tissue within an eye of a patient for the Kagan Binder, PLLC treatment of an ocular condition, the method comprising Suite 200 concurrently using at least two of the following bioactive 221 Main Street North agent delivery methods (A)-(C): Stillwater, MN 55082 (US) (A) implanting a Sustained release delivery device com (21) Appl. No.: 11/175,850 prising one or more bioactive agents in a posterior region of the eye so that it delivers the one or more (22) Filed: Jul. 5, 2005 bioactive agents into the vitreous humor of the eye; (B) instilling (e.g., injecting or implanting) one or more Related U.S. Application Data bioactive agents Subretinally; and (60) Provisional application No. 60/585,236, filed on Jul. (C) instilling (e.g., injecting or delivering by ocular ion 2, 2004. Provisional application No. 60/669,701, filed tophoresis) one or more bioactive agents into the Vit on Apr. 8, 2005. reous humor of the eye. Patent Application Publication May 25, 2006 Sheet 1 of 22 US 2006/0110428A1 R 2 2 C.6 Fig. -

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20130289061A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2013/0289061 A1 Bhide et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 31, 2013 (54) METHODS AND COMPOSITIONS TO Publication Classi?cation PREVENT ADDICTION (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: The General Hospital Corporation, A61K 31/485 (2006-01) Boston’ MA (Us) A61K 31/4458 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. (72) Inventors: Pradeep G. Bhide; Peabody, MA (US); CPC """"" " A61K31/485 (201301); ‘4161223011? Jmm‘“ Zhu’ Ansm’ MA. (Us); USPC ......... .. 514/282; 514/317; 514/654; 514/618; Thomas J. Spencer; Carhsle; MA (US); 514/279 Joseph Biederman; Brookline; MA (Us) (57) ABSTRACT Disclosed herein is a method of reducing or preventing the development of aversion to a CNS stimulant in a subject (21) App1_ NO_; 13/924,815 comprising; administering a therapeutic amount of the neu rological stimulant and administering an antagonist of the kappa opioid receptor; to thereby reduce or prevent the devel - . opment of aversion to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Also (22) Flled' Jun‘ 24’ 2013 disclosed is a method of reducing or preventing the develop ment of addiction to a CNS stimulant in a subj ect; comprising; _ _ administering the CNS stimulant and administering a mu Related U‘s‘ Apphcatlon Data opioid receptor antagonist to thereby reduce or prevent the (63) Continuation of application NO 13/389,959, ?led on development of addiction to the CNS stimulant in the subject. Apt 27’ 2012’ ?led as application NO_ PCT/US2010/ Also disclosed are pharmaceutical compositions comprising 045486 on Aug' 13 2010' a central nervous system stimulant and an opioid receptor ’ antagonist. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,264,917 B1 Klaveness Et Al

USOO6264,917B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,264,917 B1 Klaveness et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 24, 2001 (54) TARGETED ULTRASOUND CONTRAST 5,733,572 3/1998 Unger et al.. AGENTS 5,780,010 7/1998 Lanza et al. 5,846,517 12/1998 Unger .................................. 424/9.52 (75) Inventors: Jo Klaveness; Pál Rongved; Dagfinn 5,849,727 12/1998 Porter et al. ......................... 514/156 Lovhaug, all of Oslo (NO) 5,910,300 6/1999 Tournier et al. .................... 424/9.34 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (73) Assignee: Nycomed Imaging AS, Oslo (NO) 2 145 SOS 4/1994 (CA). (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 19 626 530 1/1998 (DE). patent is extended or adjusted under 35 O 727 225 8/1996 (EP). U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. WO91/15244 10/1991 (WO). WO 93/20802 10/1993 (WO). WO 94/07539 4/1994 (WO). (21) Appl. No.: 08/958,993 WO 94/28873 12/1994 (WO). WO 94/28874 12/1994 (WO). (22) Filed: Oct. 28, 1997 WO95/03356 2/1995 (WO). WO95/03357 2/1995 (WO). Related U.S. Application Data WO95/07072 3/1995 (WO). (60) Provisional application No. 60/049.264, filed on Jun. 7, WO95/15118 6/1995 (WO). 1997, provisional application No. 60/049,265, filed on Jun. WO 96/39149 12/1996 (WO). 7, 1997, and provisional application No. 60/049.268, filed WO 96/40277 12/1996 (WO). on Jun. 7, 1997. WO 96/40285 12/1996 (WO). (30) Foreign Application Priority Data WO 96/41647 12/1996 (WO). -

Phosphodiesterase (PDE)

Phosphodiesterase (PDE) Phosphodiesterase (PDE) is any enzyme that breaks a phosphodiester bond. Usually, people speaking of phosphodiesterase are referring to cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases, which have great clinical significance and are described below. However, there are many other families of phosphodiesterases, including phospholipases C and D, autotaxin, sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase, DNases, RNases, and restriction endonucleases, as well as numerous less-well-characterized small-molecule phosphodiesterases. The cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases comprise a group of enzymes that degrade the phosphodiester bond in the second messenger molecules cAMP and cGMP. They regulate the localization, duration, and amplitude of cyclic nucleotide signaling within subcellular domains. PDEs are therefore important regulators ofsignal transduction mediated by these second messenger molecules. www.MedChemExpress.com 1 Phosphodiesterase (PDE) Inhibitors, Activators & Modulators (+)-Medioresinol Di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (R)-(-)-Rolipram Cat. No.: HY-N8209 ((R)-Rolipram; (-)-Rolipram) Cat. No.: HY-16900A (+)-Medioresinol Di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside is a (R)-(-)-Rolipram is the R-enantiomer of Rolipram. lignan glucoside with strong inhibitory activity Rolipram is a selective inhibitor of of 3', 5'-cyclic monophosphate (cyclic AMP) phosphodiesterases PDE4 with IC50 of 3 nM, 130 nM phosphodiesterase. and 240 nM for PDE4A, PDE4B, and PDE4D, respectively. Purity: >98% Purity: 99.91% Clinical Data: No Development Reported Clinical Data: No Development Reported Size: 1 mg, 5 mg Size: 10 mM × 1 mL, 10 mg, 50 mg (R)-DNMDP (S)-(+)-Rolipram Cat. No.: HY-122751 ((+)-Rolipram; (S)-Rolipram) Cat. No.: HY-B0392 (R)-DNMDP is a potent and selective cancer cell (S)-(+)-Rolipram ((+)-Rolipram) is a cyclic cytotoxic agent. (R)-DNMDP, the R-form of DNMDP, AMP(cAMP)-specific phosphodiesterase (PDE) binds PDE3A directly. -

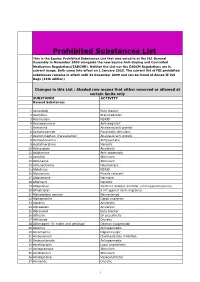

Prohibited Substances List

Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). Neither the List nor the EADCM Regulations are in current usage. Both come into effect on 1 January 2010. The current list of FEI prohibited substances remains in effect until 31 December 2009 and can be found at Annex II Vet Regs (11th edition) Changes in this List : Shaded row means that either removed or allowed at certain limits only SUBSTANCE ACTIVITY Banned Substances 1 Acebutolol Beta blocker 2 Acefylline Bronchodilator 3 Acemetacin NSAID 4 Acenocoumarol Anticoagulant 5 Acetanilid Analgesic/anti-pyretic 6 Acetohexamide Pancreatic stimulant 7 Acetominophen (Paracetamol) Analgesic/anti-pyretic 8 Acetophenazine Antipsychotic 9 Acetylmorphine Narcotic 10 Adinazolam Anxiolytic 11 Adiphenine Anti-spasmodic 12 Adrafinil Stimulant 13 Adrenaline Stimulant 14 Adrenochrome Haemostatic 15 Alclofenac NSAID 16 Alcuronium Muscle relaxant 17 Aldosterone Hormone 18 Alfentanil Narcotic 19 Allopurinol Xanthine oxidase inhibitor (anti-hyperuricaemia) 20 Almotriptan 5 HT agonist (anti-migraine) 21 Alphadolone acetate Neurosteriod 22 Alphaprodine Opiod analgesic 23 Alpidem Anxiolytic 24 Alprazolam Anxiolytic 25 Alprenolol Beta blocker 26 Althesin IV anaesthetic 27 Althiazide Diuretic 28 Altrenogest (in males and gelidngs) Oestrus suppression 29 Alverine Antispasmodic 30 Amantadine Dopaminergic 31 Ambenonium Cholinesterase inhibition 32 Ambucetamide Antispasmodic 33 Amethocaine Local anaesthetic 34 Amfepramone Stimulant 35 Amfetaminil Stimulant 36 Amidephrine Vasoconstrictor 37 Amiloride Diuretic 1 Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). -

Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Tariff Schedule 2

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACOTIAMIDUM 185106-16-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 -

Customs Tariff - Schedule

CUSTOMS TARIFF - SCHEDULE 99 - i Chapter 99 SPECIAL CLASSIFICATION PROVISIONS - COMMERCIAL Notes. 1. The provisions of this Chapter are not subject to the rule of specificity in General Interpretative Rule 3 (a). 2. Goods which may be classified under the provisions of Chapter 99, if also eligible for classification under the provisions of Chapter 98, shall be classified in Chapter 98. 3. Goods may be classified under a tariff item in this Chapter and be entitled to the Most-Favoured-Nation Tariff or a preferential tariff rate of customs duty under this Chapter that applies to those goods according to the tariff treatment applicable to their country of origin only after classification under a tariff item in Chapters 1 to 97 has been determined and the conditions of any Chapter 99 provision and any applicable regulations or orders in relation thereto have been met. 4. The words and expressions used in this Chapter have the same meaning as in Chapters 1 to 97. Issued January 1, 2019 99 - 1 CUSTOMS TARIFF - SCHEDULE Tariff Unit of MFN Applicable SS Description of Goods Item Meas. Tariff Preferential Tariffs 9901.00.00 Articles and materials for use in the manufacture or repair of the Free CCCT, LDCT, GPT, UST, following to be employed in commercial fishing or the commercial MT, MUST, CIAT, CT, harvesting of marine plants: CRT, IT, NT, SLT, PT, COLT, JT, PAT, HNT, Artificial bait; KRT, CEUT, UAT, CPTPT: Free Carapace measures; Cordage, fishing lines (including marlines), rope and twine, of a circumference not exceeding 38 mm; Devices for keeping nets open; Fish hooks; Fishing nets and netting; Jiggers; Line floats; Lobster traps; Lures; Marker buoys of any material excluding wood; Net floats; Scallop drag nets; Spat collectors and collector holders; Swivels. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0 -

BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027935 on 5 May 2019. Downloaded from BMJ Open is committed to open peer review. As part of this commitment we make the peer review history of every article we publish publicly available. When an article is published we post the peer reviewers’ comments and the authors’ responses online. We also post the versions of the paper that were used during peer review. These are the versions that the peer review comments apply to. The versions of the paper that follow are the versions that were submitted during the peer review process. They are not the versions of record or the final published versions. They should not be cited or distributed as the published version of this manuscript. BMJ Open is an open access journal and the full, final, typeset and author-corrected version of record of the manuscript is available on our site with no access controls, subscription charges or pay-per-view fees (http://bmjopen.bmj.com). If you have any questions on BMJ Open’s open peer review process please email [email protected] http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ on September 26, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. BMJ Open BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027935 on 5 May 2019. Downloaded from Treatment of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a protocol for a systematic review and evidence map Journal: BMJ Open ManuscriptFor ID peerbmjopen-2018-027935 review only Article Type: Protocol Date Submitted by the 15-Nov-2018 Author: Complete List of Authors: Dobler, Claudia; Mayo Clinic, Evidence-Based Practice Center, Robert D. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,158,152 B2 Palepu (45) Date of Patent: Apr

US008158152B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,158,152 B2 Palepu (45) Date of Patent: Apr. 17, 2012 (54) LYOPHILIZATION PROCESS AND 6,884,422 B1 4/2005 Liu et al. PRODUCTS OBTANED THEREBY 6,900, 184 B2 5/2005 Cohen et al. 2002fOO 10357 A1 1/2002 Stogniew etal. 2002/009 1270 A1 7, 2002 Wu et al. (75) Inventor: Nageswara R. Palepu. Mill Creek, WA 2002/0143038 A1 10/2002 Bandyopadhyay et al. (US) 2002fO155097 A1 10, 2002 Te 2003, OO68416 A1 4/2003 Burgess et al. 2003/0077321 A1 4/2003 Kiel et al. (73) Assignee: SciDose LLC, Amherst, MA (US) 2003, OO82236 A1 5/2003 Mathiowitz et al. 2003/0096378 A1 5/2003 Qiu et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2003/OO96797 A1 5/2003 Stogniew et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2003.01.1331.6 A1 6/2003 Kaisheva et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 1560 days. 2003. O191157 A1 10, 2003 Doen 2003/0202978 A1 10, 2003 Maa et al. 2003/0211042 A1 11/2003 Evans (21) Appl. No.: 11/282,507 2003/0229027 A1 12/2003 Eissens et al. 2004.0005351 A1 1/2004 Kwon (22) Filed: Nov. 18, 2005 2004/0042971 A1 3/2004 Truong-Le et al. 2004/0042972 A1 3/2004 Truong-Le et al. (65) Prior Publication Data 2004.0043042 A1 3/2004 Johnson et al. 2004/OO57927 A1 3/2004 Warne et al. US 2007/O116729 A1 May 24, 2007 2004, OO63792 A1 4/2004 Khera et al.