·Translating the Nation, Translating the Subaltern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on the Tribal Struggle in the Novel Kocharethi” Is the Record of Genuine Research Work Done by Me Under the Guidance of Ms

The Voice of the Unheard: A Study on the Tribal Struggle in the Novel Kocharethi Project submitted to the Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam in partial recognition of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in English Language and Literature (Model II – Teaching) Benal Benny Register Number: 170021017769 Sixth Semester Department of English St. Paul’s College Kalamassery 2017-2020 Declaration I do hereby declare that the project “The Voice of the unheard: A Study on the Tribal Struggle in the Novel Kocharethi” is the record of genuine research work done by me under the guidance of Ms. Rosy Milna, Assistant Professor, Department of English, St. Paul’s College, Kalamassery. Benal Benny Certificate This is to certify that the project work “The Voice of the Tribal Struggle n the novel Kocharethi” is a record of the original work carried out by Benal Benny under the supervision and guidance of Ms. Rosy Milna, Assistant Professor, Department of English, St. Paul’s College, Kalamassery. Dr. Salia Rex Ms. Rosy Milna Head of the Deparment Project Guide Department of English Department of English St. Paul’s College St. Paul’s College Kalamassery Kalamassery Acknowledgement I would like to thank Ms. Rosy Milna for her assistance and suggestions during the writing of this project. This work would not have taken its present shape without her painstaking scrutiny and timely interventions. I thank Dr. Salia Rex, Head of Department of English for her suggestions and corrections. I would also thank my friends, teachers and the librarian for their assistance and support. -

Mist: an Analytical Study Focusing on the Theme and Imagery of the Novel

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY– SEPT 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Mist: An Analytical Study Focusing on the Theme and Imagery of the Novel *Arya V. Unnithan Guest Lecturer, NSS College for Women, Karamana, Trivandrum, Kerala Received: May 23, 2018 Accepted: June 30, 2018 ABSTRACT Mist, the Malayalam novel is certainly a golden feather in M.T. Vasudevan Nair’s crown and is a brilliant work which has enhanced Malayalam literature’s fame across the world. This novel is truly different from M.T.’s other writings such as Randamuzham or its English translation titled Bhima. M.T. is a writer with wonderfulnarrative skills. In the novel, he combined his story- telling power with the technique of stream- of- consciousness and thereby provides readers, a brilliant reading experience. This paper attempts to analyse the novel, with special focus on its theme and imagery, thereby to point out how far the imagery and symbolism agrees with the theme of the novel. Keywords: analysis-theme-imagery-Vimala-theme of waiting- love and longing- death-stillness Introduction: Madath Thekkepaattu Vasudevan Nair, popularly known as M.T., is an Indian writer, screenplay writer and film director from the state of Kerala. He is a creative and gifted writer in modern Malayalam literature and is one of the masters of post-Independence Indian literature. He was born on 9 August 1933 in Kudallur, a village in the present day Pattambi Taluk in Palakkad district. He rose to fame at the age of 20, when he won the prize for the best short story in Malayalam at World Short Story Competition conducted by the New York Herald Tribune. -

Women at Crossroads: Multi- Disciplinary Perspectives’

ISSN 2395-4396 (Online) National Seminar on ‘Women at Crossroads: Multi- disciplinary Perspectives’ Publication Partner: IJARIIE ORGANISE BY: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PSGR KRISHNAMMAL COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, PEELAMEDU, COIMBATORE Volume-2, Issue-6, 2017 Vol-2 Issue-6 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396 A Comparative Study of the Role of Women in New Generation Malayalam Films and Serials Jibin Francis Research Scholar Department of English PSG College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Abstract This 21st century is called the era of technology, which witnesses revolutionary developments in every aspect of life. The life style of the 21st century people is very different; their attitude and culture have changed .This change of viewpoint is visible in every field of life including Film and television. Nowadays there are several realty shows capturing the attention of the people. The electronic media influence the mind of people. Different television programs target different categories of people .For example the cartoon programs target kids; the realty shows target youth. The points of view of the directors and audience are changing in the modern era. In earlier time, women had only a decorative role in the films. Their representation was merely for satisfying the needs of men. The roles of women were always under the norms and rules of the patriarchal society. They were most often presented on the screen as sexual objects .Here women were abused twice, first by the male character in the film and second, by the spectators. But now the scenario is different. The viewpoint of the directors as well as the audience has drastically changed .In this era the directors are courageous enough to make films with women as central characters. -

MA English Revised (2016 Admission)

KANNUR Li N I \/EttSIl Y (Abstract) M A Programme in English Language programnre & Lirerature undcr Credit Based semester s!.stem in affiliated colieges Revised pattern Scheme. s,'rabus and of euestion papers -rmplemenred rvith effect from 2016 admission- Orders issued. ACADEMIC C SECTION UO.No.Acad Ci. til4t 20tl Civil Srarion P.O, Dared,l5 -07-20t6. Read : l. U.O.No.Acad/Ct/ u 2. U.C of €ven No dated 20.1O.2074 3. Meeting of the Board of Studies in English(pc) held on 06_05_2016. 4. Meeting of the Board of Studies in English(pG) held on 17_06_2016. 5. Letter dated 27.06.201-6 from the Chairman, Board of Studies in English(pc) ORDER I. The Regulations lor p.G programmes under Credit Based Semester Systeln were implernented in the University with eriect from 20r4 admission vide paper read (r) above dated 1203 2014 & certain modifications were effected ro rhe same dated 05.12.2015 & 22.02.2016 respectively. 2. As per paper read (2) above, rhe Scherne Sylrabus patern - & ofquesrion papers rbr 1,r A Programme in English Language and Literature uncler Credir Based Semester System in affiliated Colleges were implcmented in the University u,.e.i 2014 admission. 3. The meeting of the Board of Studies in En8lish(pc) held on 06-05_2016 , as per paper read (3) above, decided to revise the sylrabus programme for M A in Engrish Language and Literature rve'f 2016 admission & as per paper read (4) above the tsoard of Studies finarized and recommended the scheme, sy abus and pattem of question papers ror M A programme in Engrish Language and riterature for imprementation wirh efl'ect from 20r6 admissiorr. -

Colonial Rule in Kerala and the Development of Malayalam Novels: Special Reference to the Early Malayalam Novels

RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary 2021; 6(2):01-03 Research Paper ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online) https://doi.org/10.31305/rrijm.2021.v06.i02.001 Double Blind Peer Reviewed/Refereed Journal https://www.rrjournals.com/ Colonial Rule in Kerala and the Development of Malayalam Novels: Special Reference to the Early Malayalam Novels *Ramdas V H Research Scholar, Comparative Literature and Linguistics, Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady ABSTRACT Article Publication Malayalam literature has a predominant position among other literatures. From the Published Online: 14-Feb-2021 ‘Pattu’ moments it had undergone so many movements and theories to transform to the present style. The history of Malayalam literature witnessed some important Author's Correspondence changes and movements in the history. That means from the beginning to the present Ramdas V H situation, the literary works and literary movements and its changes helped the development of Malayalam literature. It is difficult to estimate the development Research Scholar, Comparative Literature periods of Malayalam literature. Because South Indian languages like Tamil, and Linguistics, Sree Sankaracharya Kannada, etc. gave their own contributions to the development of Malayalam University of Sanskrit, Kalady literature. Especially Tamil literature gave more important contributions to the Asst.Professor, Dept. of English development of Malayalam literature. The English education was another milestone Ilahia College of Arts and Science of the development of Malayalam literature. The establishment of printing presses, ramuvh[at]gmail.com the education minutes of Lord Macaulay, etc. helped the development process. People with the influence of English language and literature, began to produce a new style of writing in Malayalam literature. -

April 2019 Sl.No

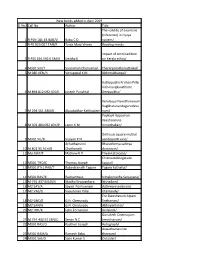

New books added in April 2019 Sl.No. Call No. Author Title The validity of anumana (inference) in nyaya 1 R PSN 181.43 BAB/V Babu C D system/ 2 R PE 823.007 TAN/R Tania Mary Vivera Reading minds: Impact of smrti tadition 3 R PSS 294.592 6 SMI/I Smitha K on Kerala ethos/ 4 M301 SIV/T Sivaraman Cheriyanad Theranjedutha kathakal/ 5 M 080 VEN/A Venugopal K M Abhimukhangal/ Kuttippuzha Krishan Pillai Vicharaviplavathinte 6 M 894.812 092 JOS/K Joseph Panakkal Deepasikha/ Keraleeya Navothanavum Vagbhatanandagurudeva 7 M 294.561 ABO/K Aboobakkar Kathiyalam num/ Poykayil Appachan Keezhalarute 8 M 303.484 092 LEN/P Lenin K M Vimochakan/ Delhousi square muthal 9 M301 VIJ/D Vijayan P N aandippatti vare/ Achuthanunni Bharatheeya sahitya 10 M 801.95 ACH/B Chathanath darsanam/ 11 M3 MAT/T Mathew K P Theekkattiloote/ Chitrasalabhagalude 12 M301 THO/C Thomas Joseph kappal/ 13 M301 (ITr.) RAB/T Rabindranath Tagore Tagore kathakal/ 14 M301 RAV/K Ravivarma p Kimakurvatha Sanjayana/ 15 M 791.437 MAD/N Madhu Ervavankara Nishadam/ 16 M2 SAY/A Sayed Ponkunnam Aathmanivedanam/ 17 M2 VAS/U Vasudevan Pillai Utampady/ Ere Dweshavum Alpam 18 M2 GNC/E G.N. Cheruvadu Snehavum/ 19 M2 SAN/A G.N. Cheruvadu Abhayarthikal/ 20 M2 JOH/K John Fernandaz Kollakolli/ Gurudeth Cinemayum 21 M 791.430 92 SEN/G Senan N C Jeevithavum/ 22 M301 KAS/O Kasthuri Joseph Autograph/ Aswathamavinte 23 M301 RAM/A Ramesh Babu theeram/ 24 M301 SAJ/O Sajiv Kumar S Outsider/ 25 M301 VEN/A Venugopalan T P Anunasikam/ Jayasankaran Kunjikrishnanmesiri 26 M301 JAY/K Puthuppalli vivahithanayi/ 27 M3 -

Tribal, Cultural Identity and Development in Narayan's Kocharethi

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Tribal, Cultural Identity and Development in Narayan’s Kocharethi - The Arya Woman Pramod Kumar Gond Research Scholar Department of English Banaras Hindu University Abstract It is widely seen that Indian society is vast and complex including multiple communities and cultures. The tribals are the most important contributors towards the origin of the Indian society. But due to lack of education, documented history and awareness, their culture has been misinterpreted and assimilated with others under the label of development. It pulls them at periphery and causes the identity crisis. In this article I focused on tribal who are facing a serious identity crisis despite its rich cultural legacy. This study is related to cultural issues, the changes, the reasons and the upliftment of tribal culture with a special reference to the Malayarayar tribes portrayed in Narayan‟s Kocherethi. Key Words: Tribal, Culture, Identity, Development and assimilations. Vol. 2, Issue 4 (March 2017) Dr. Siddhartha Sharma Page 449 Editor-in-Chief www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Tribal, Cultural Identity and Development in Narayan’s Kocharethi - The Arya Woman Pramod Kumar Gond Research Scholar Department of English Banaras Hindu University The conflict between cultural identity and development is major issue in tribal society that is emerging as a focal consideration in modern Indian literary canon. The phrases „Culture‟ and „development‟ which have not always gone together, or been worked upon within the same context. -

Issn 2454-8596

ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NARAYAN’S KOCHARETHI IN THE LIGHT OF POST- COLONIALISM Hardik Udeshi Assistant Professor Department of English Christ College, Rajkot Dr. Paresh Joshi Assistant Professor Department of English Christ College, Rajkot V o l u m e I II I s s u e 6 J u n e - 2 0 1 8 Page 1 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ABSTRACT British people have colonized almost whole world. Colonies were made and those people were convicted in different ways. The present paper proceeds from the conviction that post colonialism and ecocriticism have a great deal to gain from one another. The paper attempts to see with the perspective of how Adivasis, tribes in general are colonized not only with other people but with the people of themselves. The changes associated with globalization have led to the rapid extension and intensification of capital along with an acceleration of the destruction of the environment and a growing gap between the rich and the poor. Narayan in his novel Kocharethi shows how Malayaras are colonized with their land, customs, and traditions and with their identities. The paper will focus on the reading of novel with post-colonial perspective. Keywords: Colonization, Post Colonialism, Forest, Adivasis V o l u m e I II I s s u e 6 J u n e - 2 0 1 8 Page 2 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- History notes that the world has made into colonies by British people. -

Malayalam - Novel

NEW BOMBAY KERALEEYA SAMAJ , LIBRARY LIBRARY LIST MALAYALAM - NOVEL SR.NO: BOOK'S NAME AUTHOR TYPE 4000 ORU SEETHAKOODY A.A.AZIS NOVEL 4001 AADYARATHRI NASHTAPETTAVAR A.D. RAJAN NOVEL 4002 AJYA HUTHI A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4003 UPACHAPAM A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4004 ABHILASHANGELEE VIDA A.P.I. SADIQ NOVEL 4005 GREEN CARD ABRAHAM THECKEMURY NOVEL 4006 TARSANUM IRUMBU MANUSHYARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4007 TARSANUM KOLLAKKARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4008 PATHIMOONNU PRASNANGAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4009 ABC NARAHATHYAKAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4010 HARITHABHAKALKK APPURAM AKBAR KAKKATTIL NOVEL 4011 ENMAKAJE AMBIKA SUDAN MANGAD NOVEL 4012 EZHUTHATHA KADALAS AMRITA PRITAM NOVEL 4013 MARANA CERTIFICATE ANAND NOVEL 4014 AALKKOOTTAM ANAND NOVEL 4015 ABHAYARTHIKAL ANAND NOVEL 4016 MARUBHOOMIKAL UNDAKUNNATHU ANAND NOVEL 4017 MANGALAM RAHIM MUGATHALA NOVEL 4018 VARDHAKYAM ENDE DUKHAM ARAVINDAN PERAMANGALAM NOVEL 4019 CHORAKKALAM SIR ARTHAR KONAN DOYLE D.NOVEL 4020 THIRICHU VARAVU ASHTAMOORTHY NOVEL 4021 MALSARAM ASHWATHI NOVEL 4022 OTTAPETTAVARUDEY RATHRI BABU KILIROOR NOVEL 4023 THANAL BALAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4024 NINGAL ARIYUNNATHINE BALAKRISHNAN MANGAD NOVEL 4025 KADAMBARI BANABATTAN NOVEL 4026 ANANDAMADAM BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJI NOVEL 4027 MATHILUKAL VIKAM MOHAMMAD BASHEER NOVEL 4028 ATTACK BATTEN BOSE NOVEL 4029 DR.DEVIL BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4030 CHANAKYAPURI BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4031 RAKTHA RAKSHASSE BRAM STOCKER NOVEL 4032 NASHTAPETTAVARUDEY SANGAGANAM C.GOPINATH NOVEL 4033 PRAKRTHI NIYAMAM C.R.PARAMESHWARAN NOVEL 4034 CHUZHALI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4035 VERUKAL PADARUNNA VAZHIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4036 ATHIRUKAL KADAKKUNNAVAR C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4037 SAHADHARMINI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4038 KAANAL THULLIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4039 POOJYAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4040 KANGALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4041 THEVADISHI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4042 KANKALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4043 MRINALAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4044 KANNIMANGAKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4045 MALAKAMAAR CHIRAKU VEESHUMBOL C.V. -

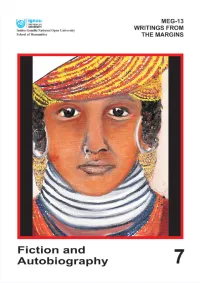

Kocharethi the Araya Woman 2.7 Let Us Sum up 2.8 Glossary 2.9 Questions 2.10 Suggested Readings

MEG-13 Writings From the Margins Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Humanities Block 7 FICTION AND AUTOBIOGRAPHY UNIT 1 Mother Forest: The Unfinished Story of C.K. Janu 5 UNIT 2 Kocharethi: The Araya Woman – Background to the Text and Context 19 UNIT 3 Kocharethi: The Araya Woman – A Study of the Novel 24 EXPERT COMMITTEE Prof. Shyamla Narayan (Retired) Prof. Satyakam Jamia Millia Islamia Director (SOH). Dr. Anand Prakash (Retired) English Faculty, SOH Delhi University Prof. Anju Sahgal Gupta Prof. Neera Singh Dr. Payal Nagpal Prof. Malati Mathur Janki Devi College Prof. Nandini Sahu Delhi University Dr. Pema E Samdup Dr. Ivy Hansdak Ms. Mridula Rashmi Kindo Jamia Millia Islamia Dr. Parmod Kumar Dr. Malthy A. Dr. Richa Bajaj Hindu College Delhi University COURSE COORDINATION AND EDITING Ms. Mridula Rashmi Kindo Dr. Anand Prakash (Retd. DU.) IGNOU Ms. Mridula Rashmi Kindo COURSE PREPARATION Dr. Ivy Hansdak Prof. Anand Mahanand (Unit 2 & 3) Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi Hyderabad University and Ms. Rajitha Venugopal (Unit 1) Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi PRINT PRODUCTION C. N. Pandey Section Officer (Publication) SOH, IGNOU, New Delhi January, 2019 Indira Gandhi National Open University, 2019 ISBN : 978-93-88498-61-6 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the Indira Gandhi National Open University. Further information on Indira Gandhi National Open University courses may be obtained from the University's office at Maidan Garhi. New Delhi-110 068 or visit University’s web site http://www.ignou.ac.in Printed and published on behalf of the Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi by Prof. -

English Books in Ksa Library

Author Title Call No. Moss N S ,Ed All India Ayurvedic Directory 001 ALL/KSA Jagadesom T D AndhraPradesh 001 AND/KSA Arunachal Pradesh 001 ARU/KSA Bullock Alan Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thinkers 001 BUL/KSA Business Directory Kerala 001 BUS/KSA Census of India 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 1 - Kannanore 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 9 - Trivandrum 001 CEN/KSA Halimann Martin Delhi Agra Fatepur Sikri 001 DEL/KSA Delhi Directory of Kerala 001 DEL/KSA Diplomatic List 001 DIP/KSA Directory of Cultural Organisations in India 001 DIR/KSA Distribution of Languages in India 001 DIS/KSA Esenov Rakhim Turkmenia :Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union 001 ESE/KSA Evans Harold Front Page History 001 EVA/KSA Farmyard Friends 001 FAR/KSA Gazaetteer of India : Kerala 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India 4V 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India : kerala State Gazetteer 001 GAZ/KSA Desai S S Goa ,Daman and Diu ,Dadra and Nagar Haveli 001 GOA/KSA Gopalakrishnan M,Ed Gazetteers of India: Tamilnadu State 001 GOP/KSA Allward Maurice Great Inventions of the World 001 GRE/KSA Handbook containing the Kerala Government Servant’s 001 HAN/KSA Medical Attendance Rules ,1960 and the Kerala Governemnt Medical Institutions Admission and Levy of Fees Rules Handbook of India 001 HAN/KSA Ker Alfred Heros of Exploration 001 HER/KSA Sarawat H L Himachal Pradesh 001 HIM/KSA Hungary ‘77 001 HUN/KSA India 1990 001 IND/KSA India 1976 : A Reference Annual 001 IND/KSA India 1999 : A Refernce Annual 001 IND/KSA India Who’s Who ,1972,1973,1977-78,1990-91 001 IND/KSA India :Questions -

STRIDE, Stride Is the Pride Newsletter of Symbiosis Law School, Hyderabad

Volume 5 - 2018 Editor : Dr. Sukhvinder Badan Singh Dari Co-Editors: Dr. Prageetha G Raju K Shanthi STRIDE, Stride is the Pride Newsletter of Symbiosis Law School, Hyderabad. The main objective of this Newsletter is to provide specialized information to the outside world about the ongoing activities on a day to day basis at our splendid campus. This earnest effort will reach the prospective law graduates who may be in search of one of the best law schools to pursue their law graduation, and for the parents who wish to see their young progenies as prolic and dynamic legal professionals. Our STRIDE standpoints for: S- Success: Being successful for the fourth consecutive year since its launch in 2015, we share the success stories of our student toppers in academics, moot-court competitions, curricular and extra- curricular activities. T-Thriving: A newsletter which thrives to give a glance of massive multitudinous events in the campus. R-Resplendent: It is lled with extensive news of the dignitary visits to the campus I-Innovative: Paves a way for the novel accomplishments D-Developing: Gives an insight of the community based development programs that provide monitoring, supervision and services to people through our legal aid centers and digital aid centers E-Eminence: Shares a vision of its in-house faculty members and students who have great zeal, and potential and are couched with prociencies and always exuberant to unveil the curricular and extra-curricular activities, to the world. 3 IN THIS ISSUE 1. Director’s Desk 05 2. Editor’s Note 06 3. Faculty team 07 4.