Kocharethi the Araya Woman 2.7 Let Us Sum up 2.8 Glossary 2.9 Questions 2.10 Suggested Readings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on the Tribal Struggle in the Novel Kocharethi” Is the Record of Genuine Research Work Done by Me Under the Guidance of Ms

The Voice of the Unheard: A Study on the Tribal Struggle in the Novel Kocharethi Project submitted to the Mahatma Gandhi University Kottayam in partial recognition of the requirements for the award of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in English Language and Literature (Model II – Teaching) Benal Benny Register Number: 170021017769 Sixth Semester Department of English St. Paul’s College Kalamassery 2017-2020 Declaration I do hereby declare that the project “The Voice of the unheard: A Study on the Tribal Struggle in the Novel Kocharethi” is the record of genuine research work done by me under the guidance of Ms. Rosy Milna, Assistant Professor, Department of English, St. Paul’s College, Kalamassery. Benal Benny Certificate This is to certify that the project work “The Voice of the Tribal Struggle n the novel Kocharethi” is a record of the original work carried out by Benal Benny under the supervision and guidance of Ms. Rosy Milna, Assistant Professor, Department of English, St. Paul’s College, Kalamassery. Dr. Salia Rex Ms. Rosy Milna Head of the Deparment Project Guide Department of English Department of English St. Paul’s College St. Paul’s College Kalamassery Kalamassery Acknowledgement I would like to thank Ms. Rosy Milna for her assistance and suggestions during the writing of this project. This work would not have taken its present shape without her painstaking scrutiny and timely interventions. I thank Dr. Salia Rex, Head of Department of English for her suggestions and corrections. I would also thank my friends, teachers and the librarian for their assistance and support. -

Shareholding Pattern 30.09.2020

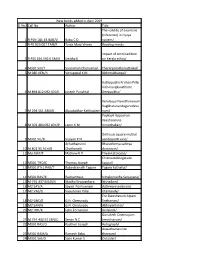

RP-SanjivGoenka '., Group , Growing Legacies cesc1VENTURES 20 October,2020 Manager (Listing) National Stock Exchange of India Limited Exchange Plaza, 5th Floor, Plot No. C/1, G- Block, Bandra – Kurla Complex, Bandra (East), Mumbai – 400 051 SCRIP CODE: CESCVENT The Secretary BSE Limited Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Dalal Street, Mumbai – 400 001 SCRIP CODE: 542333 The Secretary The Calcutta Stock Exchange Limited 7, Lyons Range, Kolkata – 700 001 SCRIP CODE:13343 Dear Sir, Shareholding Pattern under Regulation 31 of SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 In terms of Securities and Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015, we enclose herewith the shareholding pattern of the Company for the quarter ended 30 September, 2020 in the prescribed format. Yours faithfully, COMPANY SECRETARY Encl: CESC VENTURES LIMITED Regd. Office: CESC House, Chowringhee Square, Kolkata - 700 001, India e-mail : [email protected] □ Tel : +91 33 2225 6040 □ CIN : L74999WB2017PLC219318 □ Web: www.cescventures.com (Formerly known as RP-SG Business Process Services Limited) CESC VENTURES LIMITED Shareholding Pattern under Regulation 31 of SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 1. Name of Listed Entity: CESC Ventures Limited 2. Scrip Code/Name of Scrip/Class of Security: 542333 (BSE) CESCVENT ( NSE) 3. Share Holding Pattern Filed under: Reg. 31(1)(b) 4 For Quarter ending 30 September, 2020 5 Declaration: The Listed entity is required to submit the -

List of Teachers Posted from the Following Schools to Various Examination Centers As Assistant Superintendents for Higher Secondary Exam March 2015

LIST OF TEACHERS POSTED FROM THE FOLLOWING SCHOOLS TO VARIOUS EXAMINATION CENTERS AS ASSISTANT SUPERINTENDENTS FOR HIGHER SECONDARY EXAM MARCH 2015 08001 - GOVT SMT HSS,CHELAKKARA,THRISSUR 1 DILEEP KUMAR P V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04884231495, 9495222963 2 SWAPNA P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9846374117 3 SHAHINA.K 08035-GOVT. RSR VHSS, VELUR, THRISSUR 04885241085, 9447751409 4 SEENA M 08041-GOVT HSS,PAZHAYANNOOR,THRISSUR 04884254389, 9447674312 5 SEENA P.R 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872356188, 9947088692 6 BINDHU C 08062-ST ANTONY S HSS,PUDUKAD,THRISSUR 04842331819, 9961991555 7 SINDHU K 08137-GOVT. MODEL HSS FOR GIRLS, THRISSUR TOWN, , 9037873800 THRISSUR 8 SREEDEVI.S 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9020409594 9 RADHIKA.R 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742552608, 9847122431 10 VINOD P 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR , 9446146634 11 LATHIKADEVI L A 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04742482838, 9048923857 12 REJEESH KUMAR.V 08015-GOVT HSS,CHERUTHURUTHY,THRISSUR 04762831245, 9447986101 08002 - GOVT HSS,CHERPU,THRISSUR 1 PREETHY M K 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR 04802820505, 9496288495 2 RADHIKA C S 08003-GOVT MODEL GHSS, IRINJALAKKUDA, THRISSUR , 9495853650 3 THRESSIA A.O 08005-GOVT HSS,KODAKARA,THRISSUR 04802726280, 9048784499 4 SMITHA M.K 08046-AKM HSS,POOCHATTY,THRISSUR 04872317979, 8547619054 5 RADHA M.R 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872342425, 9497180518 6 JANITHA K 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872448686, 9744670871 1 7 SREELEKHA.E.S 08050-ST ANTONY S HSS,AMMADAM,THRISSUR 04872343515, 9446541276 8 APINDAS T T 08095-ST. PAULS CONVENT EHSS KURIACHIRA, THRISSUR, 04872342644, 9446627146 680006 9 M.JAMILA BEEVI 08107-SN GHSS, KANIMANGALAM, THRISSUR, 680027 , 9388553667 10 MANJULA V R 08118-TECHNICAL HSS, VARADIAM, THRISSUR, 680547 04872216227, 9446417919 11 BETSY C V 08138-GOVT. -

Women at Crossroads: Multi- Disciplinary Perspectives’

ISSN 2395-4396 (Online) National Seminar on ‘Women at Crossroads: Multi- disciplinary Perspectives’ Publication Partner: IJARIIE ORGANISE BY: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PSGR KRISHNAMMAL COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, PEELAMEDU, COIMBATORE Volume-2, Issue-6, 2017 Vol-2 Issue-6 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396 A Comparative Study of the Role of Women in New Generation Malayalam Films and Serials Jibin Francis Research Scholar Department of English PSG College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Abstract This 21st century is called the era of technology, which witnesses revolutionary developments in every aspect of life. The life style of the 21st century people is very different; their attitude and culture have changed .This change of viewpoint is visible in every field of life including Film and television. Nowadays there are several realty shows capturing the attention of the people. The electronic media influence the mind of people. Different television programs target different categories of people .For example the cartoon programs target kids; the realty shows target youth. The points of view of the directors and audience are changing in the modern era. In earlier time, women had only a decorative role in the films. Their representation was merely for satisfying the needs of men. The roles of women were always under the norms and rules of the patriarchal society. They were most often presented on the screen as sexual objects .Here women were abused twice, first by the male character in the film and second, by the spectators. But now the scenario is different. The viewpoint of the directors as well as the audience has drastically changed .In this era the directors are courageous enough to make films with women as central characters. -

MA English Revised (2016 Admission)

KANNUR Li N I \/EttSIl Y (Abstract) M A Programme in English Language programnre & Lirerature undcr Credit Based semester s!.stem in affiliated colieges Revised pattern Scheme. s,'rabus and of euestion papers -rmplemenred rvith effect from 2016 admission- Orders issued. ACADEMIC C SECTION UO.No.Acad Ci. til4t 20tl Civil Srarion P.O, Dared,l5 -07-20t6. Read : l. U.O.No.Acad/Ct/ u 2. U.C of €ven No dated 20.1O.2074 3. Meeting of the Board of Studies in English(pc) held on 06_05_2016. 4. Meeting of the Board of Studies in English(pG) held on 17_06_2016. 5. Letter dated 27.06.201-6 from the Chairman, Board of Studies in English(pc) ORDER I. The Regulations lor p.G programmes under Credit Based Semester Systeln were implernented in the University with eriect from 20r4 admission vide paper read (r) above dated 1203 2014 & certain modifications were effected ro rhe same dated 05.12.2015 & 22.02.2016 respectively. 2. As per paper read (2) above, rhe Scherne Sylrabus patern - & ofquesrion papers rbr 1,r A Programme in English Language and Literature uncler Credir Based Semester System in affiliated Colleges were implcmented in the University u,.e.i 2014 admission. 3. The meeting of the Board of Studies in En8lish(pc) held on 06-05_2016 , as per paper read (3) above, decided to revise the sylrabus programme for M A in Engrish Language and Literature rve'f 2016 admission & as per paper read (4) above the tsoard of Studies finarized and recommended the scheme, sy abus and pattem of question papers ror M A programme in Engrish Language and riterature for imprementation wirh efl'ect from 20r6 admissiorr. -

Region 10 Student Branches

Student Branches in R10 with Counselor & Chair contact August 2015 Par SPO SPO Name SPO ID Officers Full Name Officers Email Address Name Position Start Date Desc Australian Australian Natl Univ STB08001 Chair Miranda Zhang 01/01/2015 [email protected] Capital Terr Counselor LIAM E WALDRON 02/19/2013 [email protected] Section Univ Of New South Wales STB09141 Chair Meng Xu 01/01/2015 [email protected] SB Counselor Craig R Benson 08/19/2011 [email protected] Bangalore Acharya Institute of STB12671 Chair Lachhmi Prasad Sah 02/19/2013 [email protected] Section Technology SB Counselor MAHESHAPPA HARAVE 02/19/2013 [email protected] DEVANNA Adichunchanagiri Institute STB98331 Counselor Anil Kumar 05/06/2011 [email protected] of Technology SB Amrita School of STB63931 Chair Siddharth Gupta 05/03/2005 [email protected] Engineering Bangalore Counselor chaitanya kumar 05/03/2005 [email protected] SB Amrutha Institute of Eng STB08291 Chair Darshan Virupaksha 06/13/2011 [email protected] and Mgmt Sciences SB Counselor Rajagopal Ramdas Coorg 06/13/2011 [email protected] B V B College of Eng & STB62711 Chair SUHAIL N 01/01/2013 [email protected] Tech, Vidyanagar Counselor Rajeshwari M Banakar 03/09/2011 [email protected] B. M. Sreenivasalah STB04431 Chair Yashunandan Sureka 04/11/2015 [email protected] College of Engineering Counselor Meena Parathodiyil Menon 03/01/2014 [email protected] SB BMS Institute of STB14611 Chair Aranya Khinvasara 11/11/2013 [email protected] -

April 2019 Sl.No

New books added in April 2019 Sl.No. Call No. Author Title The validity of anumana (inference) in nyaya 1 R PSN 181.43 BAB/V Babu C D system/ 2 R PE 823.007 TAN/R Tania Mary Vivera Reading minds: Impact of smrti tadition 3 R PSS 294.592 6 SMI/I Smitha K on Kerala ethos/ 4 M301 SIV/T Sivaraman Cheriyanad Theranjedutha kathakal/ 5 M 080 VEN/A Venugopal K M Abhimukhangal/ Kuttippuzha Krishan Pillai Vicharaviplavathinte 6 M 894.812 092 JOS/K Joseph Panakkal Deepasikha/ Keraleeya Navothanavum Vagbhatanandagurudeva 7 M 294.561 ABO/K Aboobakkar Kathiyalam num/ Poykayil Appachan Keezhalarute 8 M 303.484 092 LEN/P Lenin K M Vimochakan/ Delhousi square muthal 9 M301 VIJ/D Vijayan P N aandippatti vare/ Achuthanunni Bharatheeya sahitya 10 M 801.95 ACH/B Chathanath darsanam/ 11 M3 MAT/T Mathew K P Theekkattiloote/ Chitrasalabhagalude 12 M301 THO/C Thomas Joseph kappal/ 13 M301 (ITr.) RAB/T Rabindranath Tagore Tagore kathakal/ 14 M301 RAV/K Ravivarma p Kimakurvatha Sanjayana/ 15 M 791.437 MAD/N Madhu Ervavankara Nishadam/ 16 M2 SAY/A Sayed Ponkunnam Aathmanivedanam/ 17 M2 VAS/U Vasudevan Pillai Utampady/ Ere Dweshavum Alpam 18 M2 GNC/E G.N. Cheruvadu Snehavum/ 19 M2 SAN/A G.N. Cheruvadu Abhayarthikal/ 20 M2 JOH/K John Fernandaz Kollakolli/ Gurudeth Cinemayum 21 M 791.430 92 SEN/G Senan N C Jeevithavum/ 22 M301 KAS/O Kasthuri Joseph Autograph/ Aswathamavinte 23 M301 RAM/A Ramesh Babu theeram/ 24 M301 SAJ/O Sajiv Kumar S Outsider/ 25 M301 VEN/A Venugopalan T P Anunasikam/ Jayasankaran Kunjikrishnanmesiri 26 M301 JAY/K Puthuppalli vivahithanayi/ 27 M3 -

Tribal, Cultural Identity and Development in Narayan's Kocharethi

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Tribal, Cultural Identity and Development in Narayan’s Kocharethi - The Arya Woman Pramod Kumar Gond Research Scholar Department of English Banaras Hindu University Abstract It is widely seen that Indian society is vast and complex including multiple communities and cultures. The tribals are the most important contributors towards the origin of the Indian society. But due to lack of education, documented history and awareness, their culture has been misinterpreted and assimilated with others under the label of development. It pulls them at periphery and causes the identity crisis. In this article I focused on tribal who are facing a serious identity crisis despite its rich cultural legacy. This study is related to cultural issues, the changes, the reasons and the upliftment of tribal culture with a special reference to the Malayarayar tribes portrayed in Narayan‟s Kocherethi. Key Words: Tribal, Culture, Identity, Development and assimilations. Vol. 2, Issue 4 (March 2017) Dr. Siddhartha Sharma Page 449 Editor-in-Chief www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Tribal, Cultural Identity and Development in Narayan’s Kocharethi - The Arya Woman Pramod Kumar Gond Research Scholar Department of English Banaras Hindu University The conflict between cultural identity and development is major issue in tribal society that is emerging as a focal consideration in modern Indian literary canon. The phrases „Culture‟ and „development‟ which have not always gone together, or been worked upon within the same context. -

AMERICAN COLLEGE JOURNAL of ENGLISH LANGUAGE and LITERATURE ( an International Refereed Research Journal of English Language and Literature )

Number 2 March 2013 ISSN: 2278 876X AMERICAN COLLEGE JOURNAL OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE ( An international refereed research journal of English Language and Literature ) Postgraduate and Research Department of English American College Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India ©ACJELL 2012 American College journal of English Language and Literature is published once a year. All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form and by any means without prior permission from the Editor, ACJELL, Postgraduate and Research Department of English, American College, Madurai, Tamilnadu, India. ISSN: 1725 2278 876X Annual Subscription International: US $ 20 India Rs.500 Cheques/ Demand Drafts may be made from any nationalized bank in favour of “The Editor, ACJELL,” Postgraduate and Research Department of English, American College payable at Madurai. To OUR FORMER PROFESSORS Who thought differently taught effectively & built the Department of English The city on a Hill EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. STANLEY MOHANDOSS STEPHEN (Editor- in- Chief) Head, Postgraduate And Research Department Of English American College, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India Dr. FRANCIS JARMAN Hildesheim University, Germany Dr. SUNDARSINGH Head, Dept. Of English, Karunya University, Coimbatore Dr. PREMILA PAUL Associate Professor, American College, Madurai Dr. DOMINIC SAVIO, Associate Professor, American College, Madurai EDITORIAL “A journal is sustained by the citations it receives” said Dr. Kalyani Mathivanan, Vice –Chancellor of Madurai- Kamaraj University, while releasing the first issue of ACJELL in September 2012. The seed is sown. We wait in silence for it to sprout. ` Out of the forty five articles received for publication, the reviewers have selected thirty four. Of these, twenty two are on Literature and twelve on Language. -

March 2020 Achievers

U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas District 1 A NOEL MASON BART SMITH District 1 BK PAUL BUTT BOB HENNESSY EVAN SHOCKLEY District 1 CN MITCH BUEHLER District 1 CS CHRIS CLARK MICHEL DAMMERMAN DARREL GRATHWOHL BILLY KELLEY BRENDA MC CLUSKIE GARY SWEITZER ANGANETTA TERRY LISA TOMAZZOLI ALAN WATT EILEEN WILKINS District 1 D VERNON DAY RONALD FLUEGEL RICHARD HOLMES MARY MENDOZA DARYL ROSENKRANS PAUL SHADDICK MONIQUE WEAVER District 1 F THOMAS FREMGEN ROBERT MC CARTY District 1 G HAROLD DEHART MARY TWADDLE District 1 H DARRELL PIERCE SARA ROBISON District 1 J SUSAN BRUNEAU MICHELE NEEDHAM DANIEL PURCELL District 1 M JOE ELKS JAMES FERRERO PAULA RIDER MIKE WALKER District 10 U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas RONALD BEACOM MARK BOSHAW DAN CRANE WILLIAM NELSON District 11 A1 LINDA CLARK District 11 A2 SONNY EPLIN SANDRA ROACH District 11 B2 MARSHA BROWN DONALD BROWN PAUL SCHINCARIOL THOMAS SHOEMAKER District 11 C1 RONALD HANSEN JOAN HEINZ LARRY HOLSTROM JENNIFER STEWARD WILLIAM SUTTON JOHN SUTTON District 11 C2 CHRISTINA ANDRE YVONNE CHRISTOPHER WILLIAMS District 11 D1 ADAM ANDERSON GARY BURROWS JASON LUOKKA District 11 D2 BRUCE BRONSON KATHERINE KELLY LARRY LATOUF WILLIAM SAMPSON DEBRA STEEB DAVID THUEMMEL District 12 L DANNY TACKER District 12 N LAURA BAILEY WILLIAM MCDONALD DAVID WATSON District 12 O JUDY BRATCHER CARLDEAN CARMACK JANIE HUGHES PETER LEGRO District 12 S SEAN DRIVER TONY GRIFFITH KATIE GUTHRIE-SHEARIN JEFF HARDY U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas JASPER SMITH ANDREA WILSON District 13 OH1 MICHEAL GIBBS REGINALD -

Issn 2454-8596

ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NARAYAN’S KOCHARETHI IN THE LIGHT OF POST- COLONIALISM Hardik Udeshi Assistant Professor Department of English Christ College, Rajkot Dr. Paresh Joshi Assistant Professor Department of English Christ College, Rajkot V o l u m e I II I s s u e 6 J u n e - 2 0 1 8 Page 1 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ABSTRACT British people have colonized almost whole world. Colonies were made and those people were convicted in different ways. The present paper proceeds from the conviction that post colonialism and ecocriticism have a great deal to gain from one another. The paper attempts to see with the perspective of how Adivasis, tribes in general are colonized not only with other people but with the people of themselves. The changes associated with globalization have led to the rapid extension and intensification of capital along with an acceleration of the destruction of the environment and a growing gap between the rich and the poor. Narayan in his novel Kocharethi shows how Malayaras are colonized with their land, customs, and traditions and with their identities. The paper will focus on the reading of novel with post-colonial perspective. Keywords: Colonization, Post Colonialism, Forest, Adivasis V o l u m e I II I s s u e 6 J u n e - 2 0 1 8 Page 2 ISSN 2454-8596 www.vidhyayanaejournal.org An International Multidisciplinary Research e-Journal ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- History notes that the world has made into colonies by British people. -

Livelihood Benefit Statement

STATEMENT OF LIVELIHOOD BENEFITS GRANTED TO HOUSE EVICTEES OF COCHIN INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT PROJECT LAC. Sl.No Year Name & Address of LAC Holder/s Benefit Beneficiary Remarks No. Poulose S/o Jacob, Chinnu W/o Poulose, Alukkaputhussery, 1 207 94 Pre Paid Taxi Chiso Paul (439) Avanamcode. 2 232 94 Pengan, S/o Palliyan, Ambattuthara Pre Paid Taxi A. P Mani (404) Kutty, W/o Pallipadan, Baby, D/o Pallipadan, Perayikkottam, External loader (DLO 3 312 94 Chandran A.K Edanadu List) Abdul Kareem, S/o Kunjumarakar, Nabeesa, W/o Abdul 4 349 94 Pre Paid Taxi Ghais P A (456) Kareem, Pallathukadavil Pre Paid Taxi Permit 5 466 94 Poulose, S/o Mathen, Puthenputhussery, Avanamcode. offered Sasi S/o Kuttappan , Eechira Kutty, Gokulan Kuttappan, External loader (DLO 6 470 94 T. K Sasi Thottathil List) Varghese S/o Mathew (Mathew Varghese), Areeckal, 7 533 94 Pre Paid Taxi Mathew Vargese (318) Avanamcode. External loader (DLO 8 635 94 Sanku Parabhakaran, Oloppilly, Thuravumkara O.S. Prabhakaran List) 9 647 94 Lakshmy W/o Prabhakaran, Padanadan AI/ GH Agencies Shibu P. P Satheesan S/o Parameswaran, Moolethu, Vasanthi W/o Pre Paid Taxi Permit 10 659 94 Satheesan, Moolethu offered 11 673 94 Jacob S/o Poulo, Kooran, Avanamcode AI/ GH Agencies Biju K. Y Pre Paid Taxi Raju K. V (141) 12 674 94 Varghese S/o Poulo, Kooran Avanamcode CIAL Staff Sheeba John 13 675 94 Poulose S/o Poulo, Kooran, Avanamcode CIAL Staff Eldho Paul 14 691 94 Palakkadi,W/o Omal Kurumban, Kizhakkumkudikoottam CIAL Staff Rajan K. K Page 1 of 55 LAC.