INTERTIDAL ZONATION Introduction to Oceanography Fall 2017 The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERTIDAL ZONATION Introduction to Oceanography Spring 2017 The

INTERTIDAL ZONATION Introduction to Oceanography Spring 2017 The Intertidal Zone is the narrow belt along the shoreline lying between the lowest and highest tide marks. The intertidal or littoral zone is subdivided broadly into four vertical zones based on the amount of time the zone is submerged. From highest to lowest, they are Supratidal or Spray Zone Upper Intertidal submergence time Middle Intertidal Littoral Zone influenced by tides Lower Intertidal Subtidal Sublittoral Zone permanently submerged The intertidal zone may also be subdivided on the basis of the vertical distribution of the species that dominate a particular zone. However, zone divisions should, in most cases, be regarded as approximate! No single system of subdivision gives perfectly consistent results everywhere. Please refer to the intertidal zonation scheme given in the attached table (last page). Zonal Distribution of organisms is controlled by PHYSICAL factors (which set the UPPER limit of each zone): 1) tidal range 2) wave exposure or the degree of sheltering from surf 3) type of substrate, e.g., sand, cobble, rock 4) relative time exposed to air (controls overheating, desiccation, and salinity changes). BIOLOGICAL factors (which set the LOWER limit of each zone): 1) predation 2) competition for space 3) adaptation to biological or physical factors of the environment Species dominance patterns change abruptly in response to physical and/or biological factors. For example, tide pools provide permanently submerged areas in higher tidal zones; overhangs provide shaded areas of lower temperature; protected crevices provide permanently moist areas. Such subhabitats within a zone can contain quite different organisms from those typical for the zone. -

Life in the Intertidal Zone

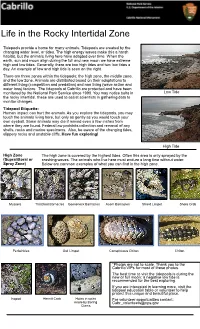

Life in the Rocky Intertidal Zone Tidepools provide a home for many animals. Tidepools are created by the changing water level, or tides. The high energy waves make this a harsh habitat, but the animals living here have adapted over time. When the earth, sun and moon align during the full and new moon we have extreme high and low tides. Generally, there are two high tides and two low tides a day. An example of low and high tide is seen on the right. There are three zones within the tidepools: the high zone, the middle zone, and the low zone. Animals are distributed based on their adaptations to different living (competition and predation) and non living (wave action and water loss) factors. The tidepools at Cabrillo are protected and have been monitored by the National Park Service since 1990. You may notice bolts in Low Tide the rocky intertidal, these are used to assist scientists in gathering data to monitor changes. Tidepool Etiquette: Human impact can hurt the animals. As you explore the tidepools, you may touch the animals living here, but only as gently as you would touch your own eyeball. Some animals may die if moved even a few inches from where they are found. Federal law prohibits collection and removal of any shells, rocks and marine specimens. Also, be aware of the changing tides, slippery rocks and unstable cliffs. Have fun exploring! High Tide High Zone The high zone is covered by the highest tides. Often this area is only sprayed by the (Supralittoral or crashing waves. -

Spatial Patterns of Macrozoobenthos Assemblages in a Sentinel Coastal Lagoon: Biodiversity and Environmental Drivers

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Spatial Patterns of Macrozoobenthos Assemblages in a Sentinel Coastal Lagoon: Biodiversity and Environmental Drivers Soilam Boutoumit 1,2,* , Oussama Bououarour 1 , Reda El Kamcha 1 , Pierre Pouzet 2 , Bendahhou Zourarah 3, Abdelaziz Benhoussa 1, Mohamed Maanan 2 and Hocein Bazairi 1,4 1 BioBio Research Center, BioEcoGen Laboratory, Faculty of Sciences, Mohammed V University in Rabat, 4 Avenue Ibn Battouta, Rabat 10106, Morocco; [email protected] (O.B.); [email protected] (R.E.K.); [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (H.B.) 2 LETG UMR CNRS 6554, University of Nantes, CEDEX 3, 44312 Nantes, France; [email protected] (P.P.); [email protected] (M.M.) 3 Marine Geosciences and Soil Sciences Laboratory, Associated Unit URAC 45, Faculty of Sciences, Chouaib Doukkali University, El Jadida 24000, Morocco; [email protected] 4 Institute of Life and Earth Sciences, Europa Point Campus, University of Gibraltar, Gibraltar GX11 1AA, Gibraltar * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This study presents an assessment of the diversity and spatial distribution of benthic macrofauna communities along the Moulay Bousselham lagoon and discusses the environmental factors contributing to observed patterns. In the autumn of 2018, 68 stations were sampled with three replicates per station in subtidal and intertidal areas. Environmental conditions showed that the range of water temperature was from 25.0 ◦C to 12.3 ◦C, the salinity varied between 38.7 and 3.7, Citation: Boutoumit, S.; Bououarour, while the average of pH values fluctuated between 7.3 and 8.0. -

Intertidal Sand and Mudflats & Subtidal Mobile

INTERTIDAL SAND AND MUDFLATS & SUBTIDAL MOBILE SANDBANKS An overview of dynamic and sensitivity characteristics for conservation management of marine SACs M. Elliott. S.Nedwell, N.V.Jones, S.J.Read, N.D.Cutts & K.L.Hemingway Institute of Estuarine and Coastal Studies University of Hull August 1998 Prepared by Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS) for the UK Marine SACs Project, Task Manager, A.M.W. Wilson, SAMS Vol II Intertidal sand and mudflats & subtidal mobile sandbanks 1 Citation. M.Elliott, S.Nedwell, N.V.Jones, S.J.Read, N.D.Cutts, K.L.Hemingway. 1998. Intertidal Sand and Mudflats & Subtidal Mobile Sandbanks (volume II). An overview of dynamic and sensitivity characteristics for conservation management of marine SACs. Scottish Association for Marine Science (UK Marine SACs Project). 151 Pages. Vol II Intertidal sand and mudflats & subtidal mobile sandbanks 2 CONTENTS PREFACE 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 I. INTRODUCTION 17 A. STUDY AIMS 17 B. NATURE AND IMPORTANCE OF THE BIOTOPE COMPLEXES 17 C. STATUS WITHIN OTHER BIOTOPE CLASSIFICATIONS 25 D. KEY POINTS FROM CHAPTER I. 27 II. ENVIRONMENTAL REQUIREMENTS AND PHYSICAL ATTRIBUTES 29 A. SPATIAL EXTENT 29 B. HYDROPHYSICAL REGIME 29 C. VERTICAL ELEVATION 33 D. SUBSTRATUM 36 E. KEY POINTS FROM CHAPTER II 43 III. BIOLOGY AND ECOLOGICAL FUNCTIONING 45 A. CHARACTERISTIC AND ASSOCIATED SPECIES 45 B. ECOLOGICAL FUNCTIONING AND PREDATOR-PREY RELATIONSHIPS 53 C. BIOLOGICAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL INTERACTIONS 58 D. KEY POINTS FROM CHAPTER III 65 IV. SENSITIVITY TO NATURAL EVENTS 67 A. POTENTIAL AGENTS OF CHANGE 67 B. KEY POINTS FROM CHAPTER IV 74 V. SENSITIVITY TO ANTHROPOGENIC ACTIVITIES 75 A. -

Wave Energy and Intertidal Productivity (Leaf Area Index/Myfilus Californianus/Postelsia/Rocky Shore/Zonation) EGBERT G

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 84, pp. 1314-1318, March 1987 Ecology Wave energy and intertidal productivity (leaf area index/Myfilus californianus/Postelsia/rocky shore/zonation) EGBERT G. LEIGH, JR.*, ROBERT T. PAINEt, JAMES F. QUINNt, AND THOMAS H. SUCHANEKt§ *Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 2072, Balboa, Panama; tDepartment of Zoology NJ-15, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195; tDivision of Environmental Studies, University of California at Davis, Davis, CA 95616; and §Bodega Marine Laboratory, P. 0. Box 247, Bodega Bay, CA 94923 Contributed by Robert T. Paine, October 20, 1986 ABSTRACT In the northeastern Pacific, intertidal zones we estimate standing crop and productivity in different zones of the most wave-beaten shores receive more energy from of exposed and sheltered rocky shores of Tatoosh Island (480 breaking waves than from the sun. Despite severe mortality 19' N, 1240 40' W), showing that intertidal productivity is from winter storms, communities at some wave-beaten sites much higher in wave-beaten settings. Finally, we consider produce an extraordinary quantity of dry matter per unit area the various roles waves may play in enhancing the produc- of shore per year. At wave-beaten sites of Tatoosh Island, WA, tivity of intertidal organisms. sea palms, Postelsia palmaeformis, can produce >10 kg of dry matter, or 1.5 x 108 J. per m2 in a good year. Extraordinarily METHODS productive organisms such as Postelsia are restricted to wave- The Power Supplied by Breaking Waves. Calculating the beaten sites. Intertidal organisms cannot transform wave power carried by waves in the open ocean. Waves generated energy into chemical energy, as photosynthetic plants trans- anywhere in the ocean-dissipate most of their energy against form solar energy, nor can intertidal organisms "harness" some shore as surf (13, 14). -

Intertidal Zonation of Two Gastropods, Nerita Plicata and Morula Granulata, in Moorea, French Polynesia

INTERTIDAL ZONATION OF TWO GASTROPODS, NERITA PLICATA AND MORULA GRANULATA, IN MOOREA, FRENCH POLYNESIA VANESSA R. WORMSER Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720 USA Abstract. Intertidal zonation of organisms is a key factor in ecological community structure and the existence of fundamental and realized niches. The zonation of two species of gastropods, Nerita plicata and Morula granulata were investigated using field observations and lab experimentation. The Nerita plicata were found on the upper limits of the intertidal zone while the Morula granulata were found on the lower limits. The distribution of each species was observed and the possible causes of this zonation were examined. Three main factors, desiccation, flow resistance and shell size were tested for their zonation. In the field, shell measurements of each species were made to see if a vertical shell size gradient existed; the results showed an upshore shell size gradient for each species. In the lab, experiments were run to see if the zonation preference found in the field existed in the lab as well. This experiment confirmed that a zonation between these species does in fact exist. Additional experiments were run to test desiccation and flow resistance between each species. A difference in desiccation rates and flow resistance were found with the Nerita plicata being more resistant to both flow and desiccation. The findings of this study provide an understanding on why zonation between these two species could exist as well as why zonation is important within an intertidal community and ecosystems as a whole. Key words: community structure; gastropod; zonation; intertidal; morphometrics; Morula granulata; Nerita plicata; Mo’orea, French Polynesia; INTRODUCTION The main goal of an ecological survey is to because of the high species diversity, the explore and understand the key dynamic convenience of the habitat as well as the easy relationships among organisms living in a collection of the sessile organisms that inhabit community (Elton 1966). -

Rocky Intertidal, Mudflats and Beaches, and Eelgrass Beds

Appendix 5.4, Page 1 Appendix 5.4 Marine and Coastline Habitats Featured Species-associated Intertidal Habitats: Rocky Intertidal, Mudflats and Beaches, and Eelgrass Beds A swath of intertidal habitat occurs wherever the ocean meets the shore. At 44,000 miles, Alaska’s shoreline is more than double the shoreline for the entire Lower 48 states (ACMP 2005). This extensive shoreline creates an impressive abundance and diversity of habitats. Five physical factors predominantly control the distribution and abundance of biota in the intertidal zone: wave energy, bottom type (substrate), tidal exposure, temperature, and most important, salinity (Dethier and Schoch 2000; Ricketts and Calvin 1968). The distribution of many commercially important fishes and crustaceans with particular salinity regimes has led to the description of “salinity zones,” which can be used as a basis for mapping these resources (Bulger et al. 1993; Christensen et al. 1997). A new methodology called SCALE (Shoreline Classification and Landscape Extrapolation) has the ability to separate the roles of sediment type, salinity, wave action, and other factors controlling estuarine community distribution and abundance. This section of Alaska’s CWCS focuses on 3 main types of intertidal habitat: rocky intertidal, mudflats and beaches, and eelgrass beds. Tidal marshes, which are also intertidal habitats, are discussed in the Wetlands section, Appendix 5.3, of the CWCS. Rocky intertidal habitats can be categorized into 3 main types: (1) exposed, rocky shores composed of steeply dipping, vertical bedrock that experience high-to- moderate wave energy; (2) exposed, wave-cut platforms consisting of wave-cut or low-lying bedrock that experience high-to-moderate wave energy; and (3) sheltered, rocky shores composed of vertical rock walls, bedrock outcrops, wide rock platforms, and boulder-strewn ledges and usually found along sheltered bays or along the inside of bays and coves. -

Intertidal Zone

INTERTIDAL ZONE The Intertidal Zone The Beach Starts in the Mountains • Glaciation, terranes, uplift, volcanism and erosion have brought rocks, sediment and sand down from the mountains through 10,000 streams to Puget Sound and created the beaches we see there. What Lives Where and Why? • Rock, sand, wave action, tidepools, exposure, temperature, light, dessication, food supply, and predation drive what can live in a particular part of the intertidal zone. • Example: Purple sea stars live under overhanging rocks and and climb up at high tide to eat barnacles and mussels on the rock. During summer storms or winter, they stay in low intertidal areas and do not feed. The level of barnacles and mussels on the rock reflects the predation of sea stars. Reproduction of sea stars is determined by the amount of light and food supply. Purple Sea Star Echinoderm Barnacles Arthropod Intertidal Zone above water at low tide & under water at high tide • May include many different types of habitats: rocks, cliffs, sand, wetlands, clay, shale, tidepools, stream outlets • Organisms in the intertidal zones are adapted to an environment of harsh extremes; sometimes submerged, exposed to sun, dessication, wave action, variable salinity, temperature extremes INTERTIDAL ZONE CARKEEK BEACH 11.0 ft -0.4 ft Intertidal Zonation on rocks at low tide Species ranges are compressed into very narrow bands Glacial erratic at Carkeek Park at low tide - encrusted with mussels, barnacles, sea stars, chitons, seaweed Intertidal Zone Organisms Life Zones of the Beach • Splash -

Primary Productivity of Intertidal Mudflats in the Wadden Sea: a Remote Sensing Method

Primary Productivity of Intertidal mudflats in the Wadden Sea: A Remote Sensing Method TIMOTHY DUBE February, 2012 SUPERVISORS: Dr. Ir. Mhd. (Suhyb). Salama Dr. Ir. C.M.M. (Chris). Mannaerts INPLACE externals: Dr. Eelke Folmer, NIOZ Prof. Dr.Jacco Kromkamp Primary Productivity of Intertidal mudflats in the Wadden Sea: A Remote Sensing Method TIMOTHY DUBE Enschede, The Netherlands, February 2012 Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation of the University of Twente in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geo-information Science and Earth Observation. Specialization: Water Resources and Environmental Management SUPERVISORS: Dr. Ir. Mhd. (Suhyb). Salama Dr. Ir. C.M.M. (Chris). Mannaerts INPLACE externals: Dr. Eelke Folmer, NIOZ Prof. Dr.Jacco Kromkamp THESIS ASSESSMENT BOARD: Prof. Dr. Ir. W. (Wouter), Verhoef (Chair) Dr. Hans van der Woerd, (External examiner, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) PRIMARY PRODUCTIVITY OF INTERTIDAL MUDFLATS IN THE WADDEN SEA: A REMOTE SENSING METHOD DISCLAIMER This document describes work undertaken as part of a programme of study at the Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation of the University of Twente. All views and opinions expressed therein remain the sole responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of the Faculty. PRIMARY PRODUCTIVITY OF INTERTIDAL MUDFLATS IN THE WADDEN SEA: A REMOTE SENSING METHOD Abstract The relative contribution of microphytobenthic (MPB) primary productivity to the total primary productivity of intertidal ecosystems is largely unknown. The possibility to estimate MPB primary productivity would be a significant contribution to a better understanding of the role of intertidal mudflats for ecosystem functioning. -

Intertidal Zones Cnidaria (Stinging Animals)

Intertidal Zones Cnidaria (stinging animals) Green anemone (Anthopleura anthogrammica) The green anemone is mainly an outer-coast species. Microscopic algae live symbiotically inside this anemone, give the anemone its green color, and provide it with food from photosynthesis. The green anemone can be solitary or live in groups, and are often found in tidepools. This anemone only reproduces sexually. Touch the anemone very gently with one wet finger and see how it feels! Aggregating anemone (Anthopleura elegantissima) The aggregating anemone reproduces both sexually and asexually. It reproduces sexually by releasing eggs and sperm into the water. To reproduce asexually, it stretches itself into an oval column, and then keeps “walking away from itself” until it splits in half. The two “cut” edges of a half-anemone heal together, forming a complete, round column, and two clones instead of one. Aggregate anemone colonies are known for fighting with other colonies of these asexually- produced clones. When different clone colonies meet they will attack each other by releasing the stinging cells in their tentacles. This warfare usually results in an open space between two competing clone colonies known as “a neutral zone”. Aggregate anemones also house symbiotic algae that give the animal its green color. The rest of the food it needs comes from prey items captured by the stinging tentacles such as small crabs, shrimp, or fish. Genetically identical, clones can colonize and completely cover rocks. Be very careful when walking on the rocks…aggregating anemones are hard to spot at first and look like sandy blobs. Watch where you step so you don’t crush anemone colonies. -

From Isla Pérez, Alacranes Reef, Southern Gulf of Mexico

Nauplius 21(2): 179-194, 2013 179 Intertidal and shallow water amphipods (Amphipoda: Gammaridea and Corophiidea) from Isla Pérez, Alacranes Reef, southern Gulf of Mexico Carlos E. Paz-Ríos, Nuno Simões and Pedro-Luis Ardisson (CEPR, PLA) Departamento de Recursos del Mar, Cinvestav, Carretera antigua a Progreso, km 6, Apdo. Postal 73, Cordemex 97310 Merida, Yucatan, Mexico. E-mails: (CEPR) [email protected]. mx (corresponding author); (PLA) [email protected] (NS) Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Facultad de Ciencias, Unidad Multidisciplinaria de Docencia e Investigacion. Puerto de Abrigo s/n. Sisal, Yucatan, Mexico. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT - Tropical coral reefs are known to exhibit high levels of biodiversity. Amphipod crustaceans are successfully adapted to a wide range of marine habitats in coral reefs, but some regions, such as the Campeche Bank in southern Gulf of Mexico, are poorly studied or even unsurveyed for amphipods. To begin to address this paucity of information, the present study records amphipod species from Isla Pérez, an island of the Alacranes Reef National Park, southern Gulf of Mexico. Twenty sites were sampled in the intertidal zone and shallow water adjacent to the island. Thirty-one species of amphipod were identified, 15 of which represented a geographical range extension to the northern Yucatan Peninsula, with four new records for the Mexican south-east sector of the Gulf of Mexico; nine for the Gulf Coast of Mexico; and two for the entire Gulf of Mexico. Significantly, a difference in faunal composition between windward and leeward areas of the intertidal zone was found. Key words: Beach, biodiversity, coral reef, Peracarida, Yucatan INTRODUCTION this biodiversity is thought to consist of small, Among the main types of coral reef (platform, cryptic species of poorly characterized faunal barrier, fringing, and atoll), those that form groups, such as crustaceans (Plaisance et al., islands (e.g. -

Beachcombers Field Guide

Beachcombers Field Guide The Beachcombers Field Guide has been made possible through funding from Coastwest and the Western Australian Planning Commission, and the Department of Fisheries, Government of Western Australia. The project would not have been possible without our community partners – Friends of Marmion Marine Park and Padbury Senior High School. Special thanks to Sue Morrison, Jane Fromont, Andrew Hosie and Shirley Slack- Smith from the Western Australian Museum and John Huisman for editing the fi eld guide. FRIENDS OF Acknowledgements The Beachcombers Field Guide is an easy to use identifi cation tool that describes some of the more common items you may fi nd while beachcombing. For easy reference, items are split into four simple groups: • Chordates (mainly vertebrates – animals with a backbone); • Invertebrates (animals without a backbone); • Seagrasses and algae; and • Unusual fi nds! Chordates and invertebrates are then split into their relevant phylum and class. PhylaPerth include:Beachcomber Field Guide • Chordata (e.g. fi sh) • Porifera (sponges) • Bryozoa (e.g. lace corals) • Mollusca (e.g. snails) • Cnidaria (e.g. sea jellies) • Arthropoda (e.g. crabs) • Annelida (e.g. tube worms) • Echinodermata (e.g. sea stars) Beachcombing Basics • Wear sun protective clothing, including a hat and sunscreen. • Take a bottle of water – it can get hot out in the sun! • Take a hand lens or magnifying glass for closer inspection. • Be careful when picking items up – you never know what could be hiding inside, or what might sting you! • Help the environment and take any rubbish safely home with you – recycle or place it in the bin. Perth• Take Beachcomber your camera Fieldto help Guide you to capture memories of your fi nds.