1-Barton-John-Of-Holme-Nottinghamshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cree Families of Newark on Trent

The Cree Families of Newark on Trent by Mike Spathaky Cree Surname Research The Cree Families of Newark on Trent by Mike Spathaky Cree Booklets The Cree Family History Society (now Cree Surname Research) was founded in 1991 to encourage research into the history and world-wide distribution of the surname CREE and of families of that name, and to collect, conserve and make available the results of that research. The series Cree Booklets is intended to further those aims by providing a channel through which family histories and related material may be published which might otherwise not see the light of day. Cree Surname Research 36 Brocks Hill Drive Oadby, Leicester LE2 5RD England. Cree Surname Research CONTENTS Chart of the descendants of Joshua Cree and Sarah Hand Joshua Cree and Sarah Hand Crees at the Muskhams - Isaac Cree and Maria Sanders The plight of single parents - the families of Joseph and Sarah Cree The open fields First published in 1994-97 as a series of articles in Cree News by the Cree Family History Society. William Cree and Mary Scott This electronic edition revised and published in 2005 by More accidents - John Cree, Ellen and Thirza Maltsters and iron founders - Francis Cree and Mary King Cree Surname Research 36 Brocks Hill Drive Fanny Cree and the boatmen of Newark Oadby Leicester LE2 5RD England © Copyright Mike Spathaky 1994-97, 2005 All Rights Reserved Elizabeth CREE b Collingham, Notts Descendants of Joshua Cree and Sarah Hand bap 10 Mar 1850 S Muskham, Notts (three generations) = 1871 Southwell+, Notts Robert -

Draft Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire

Draft recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Newark & Sherwood in Nottinghamshire Further electoral review December 2005 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact The Boundary Committee for England: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G 2 Contents Page What is The Boundary Committee for England? 5 Executive summary 7 1 Introduction 15 2 Current electoral arrangements 19 3 Submissions received 23 4 Analysis and draft recommendations 25 Electorate figures 26 Council size 26 Electoral equality 27 General analysis 28 Warding arrangements 28 a Clipstone, Edwinstowe and Ollerton wards 29 b Bilsthorpe, Blidworth, Farnsfield and Rainworth wards 30 c Boughton, Caunton and Sutton-on-Trent wards 32 d Collingham & Meering, Muskham and Winthorpe wards 32 e Newark-on-Trent (five wards) 33 f Southwell town (three wards) 35 g Balderton North, Balderton West and Farndon wards 36 h Lowdham and Trent wards 38 Conclusions 39 Parish electoral arrangements 39 5 What happens next? 43 6 Mapping 45 Appendices A Glossary and abbreviations 47 B Code of practice on written consultation 51 3 4 What is The Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. -

Minutes of the North Muskham Parish Council Meeting Held On

SUBJECT TO RATIFICATION AT THE 16th SEPTEMBER 2019 PARISH COUNCIL MEETING Minutes of the North Muskham Parish Council held on Monday, 29th July 2019 at the Muskham Rural Community Centre following the Annual Parish Meeting Present: Councillor I Harrison, in the Chair Councillor S Dolby Councillor N Hutchings Councillor D Jones Councillor P Morris Councillor D Saxton Also in attendance: County Cllr B Laughton, Dr Readman and 4 members of the public NM031-20 Apologies for absence Apologies for absence were received and accepted from Cllrs Beddoe and District Cllr Mrs Saddington. NM32-20 Declarations of interest Cllr Hutchings declared a personal and pecuniary interest in agenda item 8(a) 24 The Grange, North Muskham. It was AGREED that any other declarations of interest would be stated by Members as required during the meeting. NM33-20 Minutes The minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held on Wednesday, 26th June 2019 were accepted as a true and correct record and signed by the Chairman. NM34-20 Update on Issues Members received and noted the updated issues document, attached to the minutes as Appendix 1. NM35-20 Public 10 Minute Session The Chair suspended the meeting at 7.03pm to allow questions from members of the public. No questions were raised and the meeting was reconvened at 7.04pm. NM36-20 District Councillor Session No report was presented as Cllr Mrs Saddington had given her apologies. NM37-20 County Councillor Session The Chair suspended the meeting at 7.04pm for Cllr Laughton to present his report. Cllr Laughton confirmed that the lorry recently reported as parking overnight on Main Street had been escalated, and the District Council had spoken to GEDA. -

PLANNING SUPPORTING STATEMENT NCC Received 05/06/2017

TOWN-PLANNING.CO.UK Use of Land for the importation, storage and processing of construction and infrastructure inert waste Land Adjacent to Railway Line (Former Highways Depot), Off Great North Road, North Muskham, Newark, NG23 6HN Applicant: Laffey's Ltd PLANNING SUPPORTING STATEMENT NCC Received 05/06/2017 June 2017 South View, 16 Hounsfield Way, Sutton on Trent, Newark, Nottinghamshire, NG23 6PX Tel: 01636 822528; Mobile 07521 731789; Email: [email protected] Managing Director – Anthony Northcote, HNCert LA(P), Dip TP, PgDip URP, MA, FGS, ICIOB, MInstLM, MCMI, MRTPI TOWN-PLANNING.CO.UK is a trading name of Anthony Northcote Planning Ltd, Company Registered in England & Wales (6979909) Website: www.town-planning.co.uk TOWN-PLANNING.CO.UK Great North Road, North Muskham This planning statement has been produced by TOWN-PLANNING.CO.UK to support this individual planning proposal and the conclusions it reaches are based only upon the planning application information the LPA has made available on its website, other published information and information provided to the company by the client and/or their representatives. The author of this report is: Anthony Bryan Northcote, Managing Director of TOWN-PLANNING.CO.UK. He holds a Higher National Certificate in Land Administration (Planning) with Distinction; Diploma with Distinction in Town Planning; Post-Graduate Diploma with Distinction in Urban and Regional Planning together with a Master of Arts Degree in Urban and Regional Planning. He was elected to the Royal Town Planning Institute in 1996 and now has over 26 years planning experience within the public and private sectors involving a full range of planning issues. -

Volume 4: Spring Walks

1 Introduction Welcome to our fourth volume of ‘100 Walks from the Poppy and Pint’. This volume contains Spring Walks for you to enjoy now that the lockdown has eased. I hope that you find it useful. You will find 49 walks in this volume bringing the total number of walks in the series to 150! This volume is quite different to the other volumes. These walks have been specially selected from a wider radius of Lady Bay. This gives us more choice, more variety, and the chance to showcase different areas. Most of the walks start within 30 minutes’ drive from the Poppy and Pint and most are relatively short walks of around two to three hours. All have been chosen because they hold one or more points of interest. Moreover, the paths are quiet, they are varied, and all are on good, waymarked paths. This makes them ideal spring walks just after the lockdown. Being out on the trail in the open air anywhere lifts the spirits, is good for the soul, and gives our lives a different perspective. I think we always feel better when we come back from a walk! Do try it and see! This is the fourth volume of walks to complement Volumes One, Two and Three. Unfortunately, it is not possible to put these four volumes into one tome as the subsequent size of the file would be too big to e mail! When I set myself the challenge of researching and creating 100 local walks, I never actually thought it was possible. -

North Muskham, Bathley Lane and Church Lane; and • Whitehouses, Barnby and Bullpit Lane

What happens next? Timeline of activity East Coast Main Line (ECML) Summer 2014 Stage 1 - first round of public consultation [COMPLETE] Autumn/Winter 2014 Stage 2 - second round of public consultation ` Summer/Autumn 2015 Stage 3 – develop options and submit Transport and Works Act Order Spring 2016 Stage 4 – Public inquiry to be held (if called by the Secretary of State) 2017 – 2020 Construction Phase Level Crossing Closure Programme Feasibility Study TWAO submissions Newark & Sherwood – Norwell Lane, North An application for a Transport and Works Act Order (TWAO) for Nottinghamshire will be made and include the following crossings: Muskham, Bathley Lane and Church Lane • Scrooby, School Lane and Thomsons; • Ranskill, Torworth, Barnby Moor and Botany Bay; • Grove Road, Eaton Lane, Gamston Lane and Egmanton; • Grassthorpe, Barrel, Eaves and Carlton; • Flyfish, Cromwell Lane and Cromwell; • Norwell Lane, North Muskham, Bathley Lane and Church Lane; and • Whitehouses, Barnby and Bullpit Lane. How to respond Your comments are valued and we will consider your responses to the completed questionnaires alongside environmental, engineering design and cost considerations. We will use that information to help us design the proposed solutions that will be included in TWAO applications. Please respond to the consultation by completing the enclosed questionnaire or completing the questionnaire online at: www.networkrail.co.uk/ecmllevelcrossings Completed questionnaires can be returned to us at the public consultation events, or posted to us using -

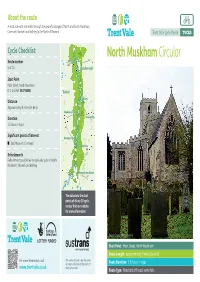

North Muskham Circular Route Number A631A666331 A631 5 of 20

About the route A short ride with some hills through the peaceful villages of North and South Muskham, Cromwell, Norwell and Bathley to the North of Newark. Trent Vale Cycle Route TVCR5 Cycle Checklist: A150 North Muskham Circular Route number A631A666331 A631 5 of 20. Start Point Main Street, North Muskham. O.S. Grid Ref. SK 796588 Distance A156 Approximately 9 miles (14 kms). A57 Duration 1.5 hours + stops. A1A Signifi cant points of interest Doll Museum, Cromwell. A46 Refreshments Refreshment possibilities in route-side pubs in North Muskham, Norwell and Bathley. A177 A1 The dots show the start points of all our 20 cycle routes. Visit our website for more information. Parish Church of St Laurence Start Point: Main Street, North Muskham Route Length: Approximately 9 miles (14 kms) For more information, visit: This series of cycle rides has been developed in partnership with the Route Duration: 1.5 hours + stops www.trentvale.co.uk charity Sustrans. Route Type: Road and off road, some hills North Muskham Circular O.S. 1:50000Sheets120and121 1 Ride through village and over the Vina Cooke A1 bridge at the Northern end of North Museum of Muskham, turning immediately right down Dolls and to the A1 using the cycle track alongside Bygone Childhood – a the Northbound lane of the A1, take care wonderful collection crossing slip road, after approx. one mile of dolls dating from leave the cycle track alongside the A1 and the 18th century along enter the village of Cromwell. with Vina’s own handmade dolls. Þ Please phone Charles Chambers on j Situated on the old Great North 01636 821364 to check opening times 2012 100022432.©NextPerspectives, 100019843.Landmark Survey anddatabaserights,2012,Ordnance copyright © Crown Road, the village of Cromwell is and admission charges. -

7 AUGUST 2018 Application No: 18/00597/FULM Proposal

PLANNING COMMITTEE – 7 AUGUST 2018 Application No: 18/00597/FULM Proposal: Proposed development of 12 affordable homes and 4 market bungalows (Re-submission of 16/01885/FULM) Location: Land at Main Street, North Muskham Applicant: Mrs M Wilson Registered: 5 April 2018 Target Date: 5 July 2018 Extension of time agreed in principle The application is being referred to Planning Committee for determination has been referred to Committee by the Business Manager for Growth and Regeneration due to the previous decision of the Planning Committee weighing in the planning balance to be applied in this instance. The Site The site comprises a rectangular shaped area of land of approximately 1.06 hectares which forms the north-east corner of a larger flat field currently used for arable farming. The site is bounded by Main Street to the east and its junction with Glebelands, to the north by a field access and beyond that The Old Hall and to the south and west by open arable fields. Beyond the arable field to the west is the A1. The Old Hall is Grade II listed building and to the north-east of the site is the Grade I listed parish landmark of St Wilfred’s Church. There are various historic buildings along Main Street, particularly close to the church, some of which are identified on the Nottinghamshire Historic Environment Record (HER) as Local Interest buildings. The majority of the built form of North Muskham is situated on the eastern side of Main Street, south of Nelson Lane. Whilst there is currently no defined village envelope for the village, the former 1999 Local Plan formerly identified this site as being outside the village envelope that was defined at that time, albeit could be considered to be adjacent to the boundary which ran down the eastern side of Main Street. -

Minutes of the North Muskham Parish Council Meeting Held on Monday

DRAFT MINUTES SUBJECT TO RATIFICATION AT 10TH SEPTEMBER MEETING Minutes of the North Muskham Parish Council held on Tuesday, 31st July 2018 at 7pm in the Muskham Rural Community Centre Present: Councillor I Harrison, in the Chair Councillor E Catanach Councillor D Jones Councillor P Morris Councillor D Saxton Also in attendance: 9 members of the public NM29-19 Apologies for absence Received and accepted from Cllrs P Beddoe and S Dolby. NM30-19 Declarations of interest It was AGREED that any declarations of interest would be stated by Members as required during the meeting. NM31-19 Minutes The minutes of the meeting held on Monday, 9th July 2018 were accepted as a true and correct record and signed by the Chairman. NM32-19 Public 10 Minute Session The Chair suspended the meeting at 7.01pm to allow members of the public present to raise any questions. No matters were raised and the meeting was reconvened at 7.03pm. NM33-19 Planning (a) 18/00597/FULM – Land at Main Street, North Muskham - Proposed development of 12 affordable homes and 4 market bungalows (Re-submission of 16/01885/FULM) Members received and noted the decision notice granting planning permission for the proposed cart shed. The Chair outlined the background to the application being before Members again. It had been submitted in late 2016, revised in September 2017 and then resubmitted in April 2018. The description had changed to ’12 affordable homes and 4 market bungalows’ and there were minor alterations with plots 14, 15 and 16 moving approximately 1m further to the south with feature planting beds now sited in front of those units and an increase in the number of new trees planted along the northern and eastern boundaries of the site. -

Minutes of the North Muskham Parish Council Meeting Held on Monday, 10Th September 2012 at 7

SUBJECT TO RATIFICATION AT THE 14th DECEMBER 2020 PARISH COUNCIL MEETING Minutes of the North Muskham Parish Council virtual meeting held on Monday, 9th November 2020 Present: Councillor I Harrison, in the Chair Councillor S Dolby Councillor N Hutchings Councillor D Saxton Councillor M Talbot Together with Councillor Mrs Saddington, County Councillor Laughton and a member of the public NM238-20 Apologies for absence An apology for absence was received and accepted from Councillor Beddoe. NM239-20 Declarations of interest Councillor Hutchings declared a personal and prejudicial interest in agenda item 3, minute number NM230-20, and would withdraw from the discussions during consideration of that minute. It was AGREED that any further declarations of interest would be stated by Members as required during the meeting. NM240-20 Minutes The minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held on Monday, 12th October 2020 were accepted as a true and correct record. NM230-20 – Planning – 7 Eastfield The Clerk confirmed that comments had been submitted to Newark & Sherwood District Council following the site meetings made by Members. While it was agreed that the application be supported Members had asked the planning authority to mitigate the concerns of neighbouring residents and seek a reduction in the ridge height. It was also requested that the concerns expressed regarding the potential lack of privacy from the rear balcony be considered, and that the visual impact of the garage to the front be assessed. The Planning Officer had forwarded a revised application which had been circulated to Members prior to the meeting, together with the link to the previous application. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2018, East Midlands

East Midlands Register 2018 HERITAGE AT RISK 2018 / EAST MIDLANDS Contents The Register III Nottingham, City of (UA) 66 Content and criteria III Nottinghamshire 68 Criteria for inclusion on the Register V Ashfield 68 Bassetlaw 69 Reducing the risks VII Broxtowe 73 Key statistics XI Gedling 74 Mansfield 75 Publications and guidance XII Newark and Sherwood 75 Key to the entries XIV Rushcliffe 78 Entries on the Register by local planning XVI Rutland (UA) 79 authority Derby, City of (UA) 1 Derbyshire 2 Amber Valley 2 Bolsover 4 Chesterfield 5 Derbyshire Dales 6 Erewash 7 High Peak 8 North East Derbyshire 10 Peak District (NP) 11 South Derbyshire 11 Leicester, City of (UA) 14 Leicestershire 17 Charnwood 17 Harborough 20 Hinckley and Bosworth 22 Melton 23 North West Leicestershire 24 Lincolnshire 25 Boston 25 East Lindsey 27 Lincoln 35 North Kesteven 37 South Holland 39 South Kesteven 41 West Lindsey 45 North East Lincolnshire (UA) 50 North Lincolnshire (UA) 52 Northamptonshire 56 Corby 56 Daventry 56 East Northamptonshire 58 Kettering 61 Northampton 61 South Northamptonshire 62 Wellingborough 65 II HERITAGE AT RISK 2018 / EAST MIDLANDS LISTED BUILDINGS THE REGISTER Listing is the most commonly encountered type of statutory protection of heritage assets. A listed building Content and criteria (or structure) is one that has been granted protection as being of special architectural or historic interest. The LISTING older and rarer a building is, the more likely it is to be listed. Buildings less than 30 years old are listed only if Definition they are of very high quality and under threat. -

Land Adjacent to Railway Line, Off Great North Road, North Muskham, Ng23 6Hn

Report to Planning and Licensing Committee 12 December 2017 Agenda Item: 8 REPORT OF CORPORATE DIRECTOR – PLACE NEWARK AN D SHERWOOD DISTRICT REF. NO.: 17/01644/FULR3N PROPOSAL: USE OF LAND FOR THE IMPORTATION, STORAGE AND PROCESSING OF CONSTRUCTION AND INFRASTRUCTURE INERT WASTE LOCATION: LAND ADJACENT TO RAILWAY LINE, OFF GREAT NORTH ROAD, NORTH MUSKHAM, NG23 6HN APPLICANT: LAFFEY'S LIMITED Purpose of Report 1. To consider a planning application seeking permission for the use of land at Great North Road, North Muskham on which to import, store and process inert wastes, including wastes arising from the Newark Waste and Water Improvement Project. The key issues relate to the principle of this type of development in the countryside having regard to the historic uses of the site; impacts to the amenity of adjacent residential properties from resultant noise; dust; from HGV traffic; and railway safeguarding issues. The recommendation is to approve a temporary planning permission for 2 years linked to the Newark Sewers project. The Site and Surroundings 2. The application site is situated beside the Great North Road and its bridge over the East Coast Railway line, to the south-west of the A1 roundabout at North Muskham, 5km north of Newark on Trent. 3. The site is a small, narrow plot of land of circa 0.28 hectares framed between the railway line to the west and the raised embankment carrying the Great North Road over the railway to the east. (See plan 1) The road then goes onto form the southwestern arm to the roundabout below the A1 flyover.