Exploring Being Queer and Performing Queerness in Popular Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soundtrack Walt Disney

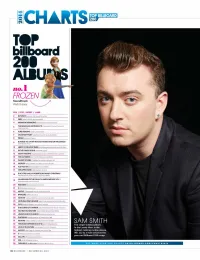

TOP BILLBOARD CHARTS200 TOP billboard 2011 ALB no.1 FROZEN Soundtrack Walt Disney POS / TITLE / ARTIST / LABEL 2 BEYONCEBeyonce Parkwood/Columbia 3 1989 TaylorSwilt Big Machine/BMW 4 MIDNIGHT MEMORIES OneOgrecuon SYCO/Columbia THE MARSHALL MAINERS LP 2 Emlnem Web/Shady/Aftermath/ Interscope/IGA 6 PURE HEROINE Lade Lava/Republic 7 CRASH MY PARTY Luke Bryan Capitol Nashville/UMGN 8 PRISM KutyPenyCapitol BLAME IT ALL ON MY ROOTS: FIVE DECADES OF INFLUENCES 9 Garth Brooks Pearl 10 HERE'S TOTHE GOODDMES RaidaGeogiaLine Republic Nastwille/BMLG 11 IN THE LONELY HOUR Sam Smith Capitol 12 NIGHT VISIONS imaginegragons KIDinaKORNER/interscope/IGA 13 THE OUTSIDERS Eric Church EMI Nashville/UPAGN 14 GHOST STORIES ColciplayParlophone/Atlantic/AG 15 NOW 50 Various Artists Sony Music/Universal/UMe 16 JUST AS I AM BrantleyGilben Valory/BMLG 17 WItAPPED IN RED KellyClarkson 19/RCA 18 DUCK THE HALLS:A ROBERTSON FAMILY CHRISIMAS TheRobertsons 4 Beards/EMI Nashville/UMGN GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: AWESOME MIX VOL.1 19 Soundtrack Marvel/Hollywood 20 PARTNERS Barbra Streisand Columbia 21 X EdSheeran Atlantic/AG 22 NATIVE OneRepublic Mosley/Interscope/IGA 23 BANGERZ MileyCyrus RCA 24 NOW 48Various Artists Sony Music/Universal/UMe 25 NOTHING WAS THE SAME Drake Young money/cash Money/Republic 26 GIRL Pharr,. amother/Columbia 27 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 5Seconds MummerHey Or Hi/Capitol 28 OLD BOOTS, NEW DIRT lasonAldean Broken Bow/BBMG 29 UNORTHODOX JUKEBOX Bruno Mars Atlantic/AG 30 PLATINUM Miranda Lambert RCA Nashville/SMN 31 NOW 49 VariousArtists Sony Music/Universal/UMe SAM SMITH 32 THE 20/20 EXPERIENa (2 OF 2) Justin Timberlake RCA The singer's debut album, 33 LOVE IN THE FUTURE lohnLegend G.O.O.D./Columbia In the Lonely Hour, is the 34 ARTPOPLadyGaga Streamline/Interscope/IGA highest-ranking rookie release 35 V Maroon5222/Interscope/IGA (No. -

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

'Insulting Comments' Against Judiciary

2/26/2016 Facebook comes under government scanner for hosting insulting comments against judiciary | Daily Mail Online Like 3.5M Follow @MailOnline DailyMail Friday, Feb 26th 2016 11AM 27°C 2PM 30°C 5Day Forecast U.K. India U.S. News Sport TV&Showbiz Femail Health Science Money Video Coffee Break Travel Columnists World News Oscars You mag Event Books Food Promos Mail Shop Bingo Blogs IPhone App Property Motoring Login Facebook comes under government Site Web Enter your search scanner for hosting 'insulting comments' DON'T MISS against judiciary Geordie Shore star By HARISH V NAIR Holly Hagan applies tanning oil to her PUBLISHED: 21:23 GMT, 22 January 2016 | UPDATED: 23:19 GMT, 22 January 2016 derriere as she shows off her ample curves in a barelythere blue bikini 19 2 on Bondi Beach shares View comments Is Adele feeling the Even as it grapples with the row over some Facebook users copying pictures of unsuspecting girls heat after turning on and misusing them by morphing the images, the popular social networking site could be in for more Sony? Upset star leaves trouble. label's BRIT Awards party early after The Ministry of Law and Justice has forwarded to the Secretary General of the Supreme Court and controversially Registrar General of the Delhi High Court “for further appropriate action” a complaint that pages dedicating her win to opened by Facebook in the name of these courts were hosting posts with comments insulting raperow Kesha various judges that were highly defamatory and contemptuous. Ready to pop! Kelly They also carried critical reviews of judgments showing the judiciary, and the judges who authored it, Clarkson shows off in poor light. -

Download (296Kb)

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Bennett, T. ORCID: 0000-0003-0078-9315 (2018). "The Whole Feminist Taking- Your-Clothes-off-Thing": Negotiating the Critique of Gender Inequality in UK Music Industries. IASPMJournal, 8(1), pp. 24-41. doi: 10.5429/2079-3871(2018)v8i1.4en This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/24616/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.5429/2079-3871(2018)v8i1.4en Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] “The Whole Feminist Taking-your- Clothes-off Thing”: Negotiating the Critique of Gender Inequality in UK Music Industries Toby Bennett Solent University [email protected] Abstract This article considers the critique of inequality, exploitation and exclusion in contemporary UK music industries, in light of the latter’s growing internal concerns over work-based gender relations. -

THE BOOK CLUB PLAY by Karen Zacarías

THE BOOK CLUB PLAY By Karen Zacarías The United States of America circa now, AD A living room This play is stylized like a film documentary. The characters know that they are being filmed but forget sometimes. Names of the experts, titles of the Books should be projected…but all the roles, including the pundits, should be live. All the dialogue should be spoken by live actors, not filmed. The set-up is a film documentary, but the language is theatrical. THIS IS NOT A FARCE; IT IS A PLAY ABOUT REAL PEOPLE. THE FUNNY SHOULD COME FROM THE HUMANITY OF THE CHARACTERS. THIS PLAY CAN BE DONE WITH 6 or 7 ACTORS. If you are using 6 actors and doubling for the pundits, then the costume changes for the pundits should be fast and minimal (1-2 articles at most). Pace and flow is vital for this play. If you are using a 7th actor for all the Pundits…then a fuller transformation can occur. The seventh actor MUST play all the PUNDIT roles: female and male. OTHER: The Book Club Play is as much about connection as it is about books. Theater patrons could write their favorite book on an adhesive name-tag as they walk into the theater, and wear it during the play to spark discussion during intermission. At the end of the performance, the stickers could be placed on a banner when they leave…so that people can see and discuss the books others have read. Book drives and video “confessionals” of reading pleasures to “Lars Knudsen” are all various easy ways to engage audiences in discussing books before, and after the play. -

Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report

City of Madison, Wisconsin Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report By Jennifer L. Lehrke, AIA, NCARB, Rowan Davidson, Associate AIA and Robert Short, Associate AIA Legacy Architecture, Inc. 605 Erie Avenue, Suite 101 Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081 and Jason Tish Archetype Historic Property Consultants 2714 Lafollette Avenue Madison, Wisconsin 53704 Project Sponsoring Agency City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development 215 Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard Madison, Wisconsin 53703 2017-2020 Acknowledgments The activity that is the subject of this survey report has been financed with local funds from the City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development. The contents and opinions contained in this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the city, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the City of Madison. The authors would like to thank the following persons or organizations for their assistance in completing this project: City of Madison Richard B. Arnesen Satya Rhodes-Conway, Mayor Patrick W. Heck, Alder Heather Stouder, Planning Division Director Joy W. Huntington Bill Fruhling, AICP, Principal Planner Jason N. Ilstrup Heather Bailey, Preservation Planner Eli B. Judge Amy L. Scanlon, Former Preservation Planner Arvina Martin, Alder Oscar Mireles Marsha A. Rummel, Alder (former member) City of Madison Muriel Simms Landmarks Commission Christina Slattery Anna Andrzejewski, Chair May Choua Thao Richard B. Arnesen Sheri Carter, Alder (former member) Elizabeth Banks Sergio Gonzalez (former member) Katie Kaliszewski Ledell Zellers, Alder (former member) Arvina Martin, Alder David W.J. McLean Maurice D. Taylor Others Lon Hill (former member) Tanika Apaloo Stuart Levitan (former member) Andrea Arenas Marsha A. -

Gonzo Weekly #165

Subscribe to Gonzo Weekly http://eepurl.com/r-VTD Subscribe to Gonzo Daily http://eepurl.com/OvPez Gonzo Facebook Group https://www.facebook.com/groups/287744711294595/ Gonzo Weekly on Twitter https://twitter.com/gonzoweekly Gonzo Multimedia (UK) http://www.gonzomultimedia.co.uk/ Gonzo Multimedia (USA) http://www.gonzomultimedia.com/ 3 gave it, when we said that it was his best album since Scary Monsters back in 1980. Yes, I think that it probably was, although the 2002 album Heathen gives it a run for its money, but with the benefit of hindsight, it still lacked the hallmarks of a classic David Bowie album, mainly because it didn't break new ground. Between 1969 and 1980 Bowie released thirteen studio albums which basically defined the decade. With the possible exception of Lodger which was basically bollocks, IMHO, each of these albums not only broke new ground, but was a significant advance upon the one that came before it. Bowie defined the concept of the rock star as artist, and where he led many others followed. Each of his stylistic changes spawned a hundred imitators. In the wake of Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane came dozens of glam bands, most of them totally missing the point, and schoolboys across the United My dear friends, Kingdom sported Ziggy haircuts. His plastic soul period not only persuaded his loyal legions that Luther Vandross was where it was at, but also meant that the 2016 is only a couple of weeks old, but we already high street outfitters were full of Oxford Bags and have the first major cultural event of the year. -

Safewow Wow Gold New Year Promo and Warcraft Director Is Leaving Awhile for His Father’S Death

Jan 13, 2016 03:24 EST Safewow wow gold New Year Promo and Warcraft Director Is Leaving awhile for His Father’s Death All love and strength to Warcraft Director, Duncan Jones from safewow - a reliable wow gold seller. It was sad to know that Jones’ father, the rock legend David Bowie was passing after 18-month battle with cancer. Condolences continue to pour in for this legend, but none more touching than the one from his son on twitter. Happy New Year!Safewow 2016 New Year Promotion II :$10 Free Cash Coupon for wow gold (Up to 12.5% off)buying during 11.12-11.22.2016 . NY3-$3 Cash code (when your order over $30) NY5-$5 Cash code (when your order over $50) NY10-$10 Cash code (when your order over $80) Welcome to join safewow 2016 Happy Wednesday for 10% off wow gold buying on 2016 every Wednesday(10% off code:WED). Duncan Jones ride on his father David Bowie’s shoulderOn Sunday evening, the horrible news was revealed on Bowie's Facebook page, showing “David Bowie died peacefully today surrounded by his family after a courageous 18 month battle with cancer”. While the news attracted broader attention from all over the world, the Warcraft director confirmed Bowie's passing to fans early Monday morning on his Twitter: “Very sorry and sad to say it’s true, I’ll be offline for a while. Love to all.” Along with the heart breaking words, Jones also shared a black-and-white image showing him ride on his daddy’s shoulder. -

KILLING BONO a Nick Hamm Film

KILLING BONO A Nick Hamm Film Production Notes Due for Release in UK: 1st April 2011 Running Time: 114 mins Killing Bono | Production Notes Press Quotes: Short Synopsis: KILLING BONO is a rock n’ roll comedy about two Irish brothers struggling to forge their path through the 1980’s music scene… whilst the meteoric rise to fame of their old school pals U2 only serves to cast them deeper into the shadows. Long Synopsis: Neil McCormick (Ben Barnes) always knew he’d be famous. A young Irish songwriter and budding genius, nothing less than a life of rock n’ roll stardom will do. But there’s only room for one singer in school band The Hype and his friend Paul’s already bagged the job. So Neil forms his own band with his brother Ivan (Robert Sheehan), determined to leave The Hype in his wake. There’s only one problem: The Hype have changed their name. To ‘U2’. And Paul (Martin McCann) has turned into ‘Bono’. Naturally there’s only one option for Neil: become bigger than U2. The brothers head to London in their quest for fame, but they are blighted by the injustices of the music industry, and their every action is dwarfed by the soaring success of their old school rivals. Then, just as they land some success of their own, Ivan discovers the shocking truth behind Neil’s rivalry with U2, and it threatens to destroy everything. As his rock n’ roll dream crashes and burns, Neil feels like his failure is directly linked to Bono’s success.