Fall 2016 Newsletter Pages.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soviet Central Asia and the Preservation of History

humanities Article Soviet Central Asia and the Preservation of History Craig Benjamin Frederik J Meijer Honors College, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, MI 49401, USA; [email protected] Received: 23 May 2018; Accepted: 9 July 2018; Published: 20 July 2018 Abstract: Central Asia has one of the deepest and richest histories of any region on the planet. First settled some 6500 years ago by oasis-based farming communities, the deserts, steppe and mountains of Central Asia were subsequently home to many pastoral nomadic confederations, and also to large scale complex societies such as the Oxus Civilization and the Parthian and Kushan Empires. Central Asia also functioned as the major hub for trans-Eurasian trade and exchange networks during three distinct Silk Roads eras. Throughout much of the second millennium of the Common Era, then under the control of a succession of Turkic and Persian Islamic dynasties, already impressive trading cities such as Bukhara and Samarkand were further adorned with superb madrassas and mosques. Many of these suffered destruction at the hands of the Mongols in the 13th century, but Timur and his Timurid successors rebuilt the cities and added numerous impressive buildings during the late-14th and early-15th centuries. Further superb buildings were added to these cities by the Shaybanids during the 16th century, yet thereafter neglect by subsequent rulers, and the drying up of Silk Roads trade, meant that, by the mid-18th century when expansive Tsarist Russia began to incorporate these regions into its empire, many of the great pre- and post-Islamic buildings of Central Asia had fallen into ruin. -

Title Change of Suspension Systems of Daggers and Swords in Eastern

Change of suspension systems of daggers and swords in eastern Title Eurasia: Its relation to the Hephthalite occupation of Central Asia Author(s) Kageyama, Etsuko Citation ZINBUN (2016), 46: 199-212 Issue Date 2016-03 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/209942 © Copyright March 2016, Institute for Research in Humanities Right Kyoto University. Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University ZINBUN No. 46 2015 Varia Change of suspension systems of daggers and swords in eastern Eurasia: Its relation to the Hephthalite occupation of Central Asia Etsuko KAGEYAMA ABSTRACT: This paper focuses on changes in the suspension systems of daggers and swords in pre- Islamic eastern Eurasia. Previous studies have shown that scabbard slides were used in the Kushan and early Sasanian periods to suspend a sword from a bearer’s waist belt. This method was later replaced by a “two-point suspension system” with which a sword is suspended by two straps and two fixtures attached on its scabbard. Through an examination of daggers and swords represented in Central Asian art, I consider the possibility that the two-point suspension system became prevalent in eastern Eurasia in connection with the Hephthalite occupation of Central Asia from the second half of the fifth century through the first half of the sixth century. KEYWORDS: Hephthalites, Sogdians, Central Asia, bladed weapons, Shōsō-in Etsuko KAGEYAMA is Associate Fellow at Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties. * This paper is based on my article published in Japanese: E. Kageyama, “Change of sus- pension systems of daggers and swords in eastern Eurasia: Its relation to the Hephthalite occupation of Central Asia”, Studies on the Inner Asian Languages 30, 2015, pp. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

Introduction

Introduction The H"’ Cen, A.D, was the most progressive time in Persian science, culture, art, literature and philosophy; and it too can be held as the glorious period of the world. Some of the great rulers such as Samanides, Khwarezmids, Ma’munids, Bavandies, al-e-Ziar, al-e-Buye and Deyalamides, etc., were governing over the Persian land for a long time, and during their regimes all the scientists, writers, poets, artists and philosophers were encouraged.' Two hundred years after the scholars like Biruni (973-1048 A.D.), Ibn Sina (Avicenna) (980-1037 A.D.), Ferdowsi (940-1020 A.D.) Khayyam (1048-1122 A.D.), Ghazzali (1058-1111 A.D.), and Nasir al-Din Tusi (1201- 1274 A.D.), were settled in the European Universities such as Paris, Oxford and Cambridge (1800-1828 A.D.). And works of the above mentioned scholars were translated from Persian into Latin, and used by European scholars. Therefore, the historians and orientalists enumerated and illustrated the effects of these scientists and re-published their works, and evaluated them in an appropriate way.^ All significant personalities of this period had lot of researches in different subjects. Among these scholars, this thesis concentrates only on Biruni and his comparative method used for philosophisation, which is significant for research, especially for studying different ancient Indian philosophical traditions and various sects of them. Biruni (973-1048A.D.) can be claimed as one of the most outstanding figure in the history of science, philosophy and comparative religions of the entire worlds. He seems to be the pioneer in various fields of sciences such as mathematic, astrology, physics, pharmacology, mineralogy, etc., and also historiography, anthropology and linguistics. -

Silk Road and Buddhism in Central Asia

SILK ROAD AND BUDDHISM IN CENTRAL ASIA 1ARCHANA GUPTA, 2ARADHANA GUPTA, 3AKANKSHA GUPTA 1School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi India 2Work as Librarian in Jawahar Navodaya Vidhyalaya, India 3School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi India E-mail: [email protected] Abstract- The Silk Route is the ‘Ancient International Trade Road’ that spread from China to Italy existed from second century BC to fifteenth century AD. Although it was known for trade which carried silk, paper and other goods between East and West through India, China and Central Asia. It also became a channel of transmission of art, architecture, culture, religion, philosophy, literature, technology etc to different countries in Asia and beyond. One of the important religions that transmitted through Silk Road was Buddhism which developed in India. It is interesting to note that Silk Road turned as the springboard of Buddhism to spread it from India to Central Asia. The Buddhist Religion originated in India. Through Buddha’s enlightenment and with his teachings, it became one of the most important “World Religions” in past. It was the first religious philosophy which transmitted along this trade route from India to China through Gandhara which is recognized in modern time northern Pakistan and southern Afghanistan. After long Centuries Islam began and it followed the same Silk route and replace Buddhism from some places. Judaism and Christianity also followed the Silk route for spread their ideology & philosophy. The proposed Article intends to examine the role of Silk Road in the spread of Buddhism from India to Central Asia. -

Resources for the Study of Islamic Architecture Historical Section

RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION Prepared by: Sabri Jarrar András Riedlmayer Jeffrey B. Spurr © 1994 AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION BIBLIOGRAPHIC COMPONENT Historical Section, Bibliographic Component Reference Books BASIC REFERENCE TOOLS FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE This list covers bibliographies, periodical indexes and other basic research tools; also included is a selection of monographs and surveys of architecture, with an emphasis on recent and well-illustrated works published after 1980. For an annotated guide to the most important such works published prior to that date, see Terry Allen, Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass., 1979 (available in photocopy from the Aga Khan Program at Harvard). For more comprehensive listings, see Creswell's Bibliography and its supplements, as well as the following subject bibliographies. GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND PERIODICAL INDEXES Creswell, K. A. C. A Bibliography of the Architecture, Arts, and Crafts of Islam to 1st Jan. 1960 Cairo, 1961; reprt. 1978. /the largest and most comprehensive compilation of books and articles on all aspects of Islamic art and architecture (except numismatics- for titles on Islamic coins and medals see: L.A. Mayer, Bibliography of Moslem Numismatics and the periodical Numismatic Literature). Intelligently organized; incl. detailed annotations, e.g. listing buildings and objects illustrated in each of the works cited. Supplements: [1st]: 1961-1972 (Cairo, 1973); [2nd]: 1972-1980, with omissions from previous years (Cairo, 1984)./ Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography, ed. Terry Allen. Cambridge, Mass., 1979. /a selective and intelligently organized general overview of the literature to that date, with detailed and often critical annotations./ Index Islamicus 1665-1905, ed. -

Culture and Customs of the Central Asian Republics

Culture and Customs of the Central Asian Republics Rafis Abazov Greenwood Press CULTURE AND CUSTOMS OF THE CENTRAL ASIAN REPUBLICS The Central Asian Republics. Cartography by Bookcomp, Inc. Culture and Customs of the Central Asian Republics 4 RAFIS ABAZOV Culture and Customs of Asia Hanchao Lu, Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Abazov, Rafi s. Culture and customs of the Central Asian republics / Rafi s Abazov. p. cm. — (Culture and customs of Asia, ISSN 1097–0738) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–33656–3 (alk. paper) 1. Asia, Central—History. 2. Asia, Central—Social life and customs. I. Title. DK859.5.A18 2007 958—dc22 2006029553 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2007 by Rafi s Abazov All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2006029553 ISBN: 0–313–33656–3 ISSN: 1097–0738 First published in 2007 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Series Foreword vii Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Notes on Transliteration xvii Chronology xxi 1 Introduction: Land, People, and History 1 2 Thought and Religion 59 3 Folklore and Literature 79 4 Media and Cinema 105 5 Performing Arts 133 6 Visual Arts 163 7 Architecture 191 8 Gender, Courtship, and Marriage 213 9 Festivals, Fun, and Leisure 233 Glossary 257 Selected Bibliography 263 Index 279 Series Foreword Geographically, Asia encompasses the vast area from Suez, the Bosporus, and the Ural Mountains eastward to the Bering Sea and from this line southward to the Indonesian archipelago, an expanse that covers about 30 percent of our earth. -

The Kushans and the Emergence of the Early Silk Roads

The Kushans and the Emergence of the Early Silk Roads A thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Departments of Archaeology and History (joint) By Paul Wilson Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2020 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. 1 Abstract: The Kushans and the Emergence of the Early Silk Roads The Kushans were a major historical power on the ancient Silk Roads, although their influence has been greatly overshadowed by that of China, Rome and Parthia. That the Kushans are so little known raises many questions about the empire they built and the role they played in the political and cultural dynamics of the period, particularly the emerging Silk Roads network. Despite building an empire to rival any in the ancient world, conventional accounts have often portrayed the Kushans as outsiders, and judged them merely in the context of neighbouring ‘superior’ powers. By examining the materials from a uniquely Kushan perspective, new light will be cast on this key Central Asian society, the empire they constructed and the impact they had across the region. Previous studies have tended to focus, often in isolation, on either the archaeological evidence available or the historical literary sources, whereas this thesis will combine understanding and assessments from both fields to produce a fuller, more deeply considered, profile. -

Fantastic Beasts of the Eurasian Steppes: Toward a Revisionist Approach to Animal-Style Art

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Fantastic Beasts Of The Eurasian Steppes: Toward A Revisionist Approach To Animal-Style Art Petya Andreeva University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Andreeva, Petya, "Fantastic Beasts Of The Eurasian Steppes: Toward A Revisionist Approach To Animal- Style Art" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2963. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2963 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2963 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fantastic Beasts Of The Eurasian Steppes: Toward A Revisionist Approach To Animal-Style Art Abstract Animal style is a centuries-old approach to decoration characteristic of the various cultures which flourished along the urE asian steppe belt in the later half of the first millennium BCE. This astv territory stretching from the Mongolian Plateau to the Hungarian Plain, has yielded hundreds of archaeological finds associated with the early Iron Age. Among these discoveries, high-end metalwork, textiles and tomb furniture, intricately embellished with idiosyncratic zoomorphic motifs, stand out as a recurrent element. While scholarship has labeled animal-style imagery as scenes of combat, this dissertation argues against this overly simplified classification model which ignores the variety of visual tools employed in the abstraction of fantastic hybrids. I identify five primary categories in the arrangement and portrayal of zoomorphic designs: these traits, frequently occurring in clusters, constitute the first comprehensive definition of animal-style art. -

Sogdian Textile Design: Political Symbols of an Epoch

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2012 Sogdian Textile Design: Political Symbols of an Epoch Elmira Gyul Tashkent State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Gyul, Elmira, "Sogdian Textile Design: Political Symbols of an Epoch" (2012). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 689. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/689 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Sogdian Textile Design: Political Symbols of an Epoch Elmira Gyul [email protected] The history of Central Asia includes a particular period when textiles and politics were directly connected with each other; it started in the Early Middle Ages, where travellers and merchants were active on the Great Silk Road. Silk trade became a main occupation at that time. Thin silk threads connected different civilizations creating an exchange of cultural traditions, religions and technologies from the West to the East and back. Silk became a kind of international currency, and a prestige symbol. The desire to possess these fabrics and to control the routes and trade of the Silk Road led politicians either to forge friendships and unions or to declare wars. In essence, possession of silk became a way to achieve supremacy by regulating societal and economic relationships in everyday life. -

Notes on the Lighting Devices in the Medicine Buddha Transformation Tableau in Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang by Sha Wutian 沙武田

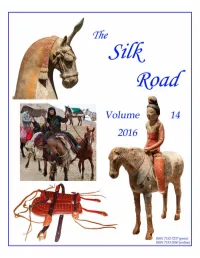

ISSN 2152-7237 (print) ISSN 2153-2060 (online) The Silk Road Volume 14 2016 Contents From the editor’s desktop: The Future of The Silk Road ....................................................................... [iii] Reconstruction of a Scythian Saddle from Pazyryk Barrow № 3 by Elena V. Stepanova .............................................................................................................. 1 An Image of Nighttime Music and Dance in Tang Chang’an: Notes on the Lighting Devices in the Medicine Buddha Transformation Tableau in Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang by Sha Wutian 沙武田 ................................................................................................................ 19 The Results of the Excavation of the Yihe-Nur Cemetery in Zhengxiangbai Banner (2012-2014) by Chen Yongzhi 陈永志, Song Guodong 宋国栋, and Ma Yan 马艳 .................................. 42 Art and Religious Beliefs of Kangju: Evidence from an Anthropomorphic Image Found in the Ugam Valley (Southern Kazakhstan) by Aleksandr Podushkin .......................................................................................................... 58 Observations on the Rock Reliefs at Taq-i Bustan: A Late Sasanian Monument along the “Silk Road” by Matteo Compareti ................................................................................................................ 71 Sino-Iranian Textile Patterns in Trans-Himalayan Areas by Mariachiara Gasparini ....................................................................................................... -

Spread of Hindu Religious Ideas in Xinjiang, China, Fourth–Seventh Centuries CE

Indian Journal of History of Science, 51.4 (2016) 659-668 DOI: 10.16943/ijhs/2016/v51/i4/41242 Ka Iconography in Khotan Carpets: Spread of Hindu Religious Ideas in Xinjiang, China, Fourth–Seventh Centuries CE Zhang He* (Received 07 December 2015) Abstract The article is a continued research study focusing on the significance of the appearance of Ka iconography in Khotan as evidence of the spreading of the Ka worship of Hinduism from India to Xinjiang, northwest China, during the time of Gupta dynasty. Several issues are discussed: accounts of the presence of Hindu religions in Khotan and other places in Xinjiang, art with large quantities of Hindu deities, and historical records of the prevalence of Hindu religions in northern India, Kashmir, and Central Asia. The study suggests that Khotan received Hindu influences beginning from the Kuāna time, and especially during the Gupta period. There was likely a community of Hindu believers in Khotan between the third and seventh centuries of Common Era. Key words: Hindu Art, Knotted Carpet, Khotan, Ka, Silk Road, Textile. 1. BACKGROUND One of the two (Fig. 1) has an additional inscription in Br hmi script woven into the carpet In 2008, near an ancient cemetery in ā Shanpula, Luopu (Lop) County, Hetian (Khotan) District, Xinjiang, China, there were discovered five knotted-pile carpets, woven on a wool foundation. The carpets were initially photographed and published in 2010 by Qi Xiaoshan, a professional photographer then at the Institute of Archaeology of Xinjiang (Urumqi). They were dated to the fourth to the sixth century CE by Wang Bo of the Xinjiang Museum (Urumqi) and the Commission of Authentication of Cultural Relics (personal communication, 2011).