Light-Dependent RNA Interference with Nucleobase-Caged Sirnas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nucleotide Metabolism

NUCLEOTIDE METABOLISM General Overview • Structure of Nucleotides Pentoses Purines and Pyrimidines Nucleosides Nucleotides • De Novo Purine Nucleotide Synthesis PRPP synthesis 5-Phosphoribosylamine synthesis IMP synthesis Inhibitors of purine synthesis Synthesis of AMP and GMP from IMP Synthesis of NDP and NTP from NMP • Salvage pathways for purines • Degradation of purine nucleotides • Pyrimidine synthesis Carbamoyl phosphate synthesisOrotik asit sentezi • Pirimidin nükleotitlerinin yıkımı • Ribonükleotitlerin deoksiribonükleotitlere dönüşümü Basic functions of nucleotides • They are precursors of DNA and RNA. • They are the sources of activated intermediates in lipid and protein synthesis (UDP-glucose→glycogen, S-adenosylmathionine as methyl donor) • They are structural components of coenzymes (NAD(P)+, FAD, and CoA). • They act as second messengers (cAMP, cGMP). • They play important role in carrying energy (ATP, etc). • They play regulatory roles in various pathways by activating or inhibiting key enzymes. Structures of Nucleotides • Nucleotides are composed of 1) A pentose monosaccharide (ribose or deoxyribose) 2) A nitrogenous base (purine or pyrimidine) 3) One, two or three phosphate groups. Pentoses 1.Ribose 2.Deoxyribose •Deoxyribonucleotides contain deoxyribose, while ribonucleotides contain ribose. •Ribose is produced in the pentose phosphate pathway. Ribonucleotide reductase converts ribonucleoside diphosphate deoxyribonucleotide. Nucleotide structure-Base 1.Purine 2.Pyrimidine •Adenine and guanine, which take part in the structure -

2'-Deoxyguanosine Toxicity for B and Mature T Lymphoid Cell Lines Is Mediated by Guanine Ribonucleotide Accumulation

2'-deoxyguanosine toxicity for B and mature T lymphoid cell lines is mediated by guanine ribonucleotide accumulation. Y Sidi, B S Mitchell J Clin Invest. 1984;74(5):1640-1648. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI111580. Research Article Inherited deficiency of the enzyme purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) results in selective and severe T lymphocyte depletion which is mediated by its substrate, 2'-deoxyguanosine. This observation provides a rationale for the use of PNP inhibitors as selective T cell immunosuppressive agents. We have studied the relative effects of the PNP inhibitor 8- aminoguanosine on the metabolism and growth of lymphoid cell lines of T and B cell origin. We have found that 2'- deoxyguanosine toxicity for T lymphoblasts is markedly potentiated by 8-aminoguanosine and is mediated by the accumulation of deoxyguanosine triphosphate. In contrast, the growth of T4+ mature T cell lines and B lymphoblast cell lines is inhibited by somewhat higher concentrations of 2'-deoxyguanosine (ID50 20 and 18 microM, respectively) in the presence of 8-aminoguanosine without an increase in deoxyguanosine triphosphate levels. Cytotoxicity correlates instead with a three- to fivefold increase in guanosine triphosphate (GTP) levels after 24 h. Accumulation of GTP and growth inhibition also result from exposure to guanosine, but not to guanine at equimolar concentrations. B lymphoblasts which are deficient in the purine salvage enzyme hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase are completely resistant to 2'-deoxyguanosine or guanosine concentrations up to 800 microM and do not demonstrate an increase in GTP levels. Growth inhibition and GTP accumulation are prevented by hypoxanthine or adenine, but not by 2'-deoxycytidine. -

Genetic Variation in Phosphodiesterase (PDE) 7B in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Overview of Genetic Variants of Cyclic Nucleotide Pdes in Human Disease

Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 56, 676–681 & 2011 The Japan Society of Human Genetics All rights reserved 1434-5161/11 $32.00 www.nature.com/jhg ORIGINAL ARTICLE Genetic variation in phosphodiesterase (PDE) 7B in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: overview of genetic variants of cyclic nucleotide PDEs in human disease Ana M Peiro´ 1,2, Chih-Min Tang1, Fiona Murray1,3, Lingzhi Zhang1, Loren M Brown1, Daisy Chou1, Laura Rassenti4, Thomas A Kipps3,4 and Paul A Insel1,3,4 Expression of cyclic adenosine monophosphate-specific phosphodiesterase 7B (PDE7B) mRNA is increased in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), thus suggesting that variation may occur in the PDE7B gene in CLL. As genetic variation in other PDE family members has been shown to associate with numerous clinical disorders (reviewed in this manuscript), we sought to identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the PDE7B gene promoter and coding region of 93 control subjects and 154 CLL patients. We found that the PDE7B gene has a 5¢ non-coding region SNP À347C4T that occurs with similar frequency in CLL patients (1.9%) and controls (2.7%). Tested in vitro, À347C4T has less promoter activity than a wild-type construct. The low frequency of this 5¢ untranslated region variant indicates that it does not explain the higher PDE7B expression in patients with CLL but it has the potential to influence other settings that involve a role for PDE7B. Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 56, 676–681; doi:10.1038/jhg.2011.80; published online 28 July 2011 Keywords: cAMP; chronic lymphocytic -

Nucleotide Metabolism 22

Nucleotide Metabolism 22 For additional ancillary materials related to this chapter, please visit thePoint. I. OVERVIEW Ribonucleoside and deoxyribonucleoside phosphates (nucleotides) are essential for all cells. Without them, neither ribonucleic acid (RNA) nor deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) can be produced, and, therefore, proteins cannot be synthesized or cells proliferate. Nucleotides also serve as carriers of activated intermediates in the synthesis of some carbohydrates, lipids, and conjugated proteins (for example, uridine diphosphate [UDP]-glucose and cytidine diphosphate [CDP]- choline) and are structural components of several essential coenzymes, such as coenzyme A, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD[H2]), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD[H]), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP[H]). Nucleotides, such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), serve as second messengers in signal transduction pathways. In addition, nucleotides play an important role as energy sources in the cell. Finally, nucleotides are important regulatory compounds for many of the pathways of intermediary metabolism, inhibiting or activating key enzymes. The purine and pyrimidine bases found in nucleotides can be synthesized de novo or can be obtained through salvage pathways that allow the reuse of the preformed bases resulting from normal cell turnover. [Note: Little of the purines and pyrimidines supplied by diet is utilized and is degraded instead.] II. STRUCTURE Nucleotides are composed of a nitrogenous base; a pentose monosaccharide; and one, two, or three phosphate groups. The nitrogen-containing bases belong to two families of compounds: the purines and the pyrimidines. A. Purine and pyrimidine bases Both DNA and RNA contain the same purine bases: adenine (A) and guanine (G). -

De Novo Deoxyribonucleotide Biosynthesis Regulates Cell Growth

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN De novo deoxyribonucleotide biosynthesis regulates cell growth and tumor progression in small‑cell lung carcinoma Ami Maruyama1,2,3, Yuzo Sato1,2,4,5, Joji Nakayama1,2,3, Junko Murai4,5, Takamasa Ishikawa5,6, Tomoyoshi Soga4,5 & Hideki Makinoshima1,2,3,7* Deoxyribonucleotide biosynthesis from ribonucleotides supports the growth of active cancer cells by producing building blocks for DNA. Although ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) is known to catalyze the rate‑limiting step of de novo deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate (dNTP) synthesis, the biological function of the RNR large subunit (RRM1) in small‑cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) remains unclear. In this study, we established siRNA‑transfected SCLC cell lines to investigate the anticancer efect of silencing RRM1 gene expression. We found that RRM1 is required for the full growth of SCLC cells both in vitro and in vivo. In particular, the deletion of RRM1 induced a DNA damage response in SCLC cells and decreased the number of cells with S phase cell cycle arrest. We also elucidated the overall changes in the metabolic profle of SCLC cells caused by RRM1 deletion. Together, our fndings reveal a relationship between the deoxyribonucleotide biosynthesis axis and key metabolic changes in SCLC, which may indicate a possible link between tumor growth and the regulation of deoxyribonucleotide metabolism in SCLC. Small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) is a neuroendocrine tumor subtype of lung cancer, and it is associated with a poor prognosis1–3. In particular, SCLC is characterized by early and widespread metastatic dissemination and a remarkable response to chemotherapy that is almost invariably followed by the development of drug resistance4. -

Oxidative Stress and the Guanosine Nucleotide Triphosphate Pool: Implications for a Biomarker and Mechanism of Impaired Cell Function

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2008 OXIDATIVE STRESS AND THE GUANOSINE NUCLEOTIDE TRIPHOSPHATE POOL: IMPLICATIONS FOR A BIOMARKER AND MECHANISM OF IMPAIRED CELL FUNCTION Celeste Maree Bolin The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Bolin, Celeste Maree, "OXIDATIVE STRESS AND THE GUANOSINE NUCLEOTIDE TRIPHOSPHATE POOL: IMPLICATIONS FOR A BIOMARKER AND MECHANISM OF IMPAIRED CELL FUNCTION" (2008). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 728. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/728 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OXIDATIVE STRESS AND THE GUANOSINE NUCLEOTIDE TRIPHOSPHATE POOL: IMPLICATIONS FOR A BIOMARKER AND MECHANISM OF IMPAIRED CELL FUNCTION By Celeste Maree Bolin B.A. Chemistry, Whitman College, Walla Walla, WA 2001 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Toxicology The University of Montana Missoula, Montana Spring 2008 Approved by: Dr. David A. Strobel, Dean Graduate School Dr. Fernando Cardozo-Pelaez, -

Deoxyguanosine Triphosphate Analogue Inhibitors of HIV Reverse Transcriptase with Human Mitochondrial DNA Polymerase Γ

Anderson 16/2/07 15:13 Page 25 Antiviral Chemistry & Chemotherapy 18:25–33 Interaction of 2′-deoxyguanosine triphosphate analogue inhibitors of HIV reverse transcriptase with human mitochondrial DNA polymerase γ Adrian S Ray1†, Joy Y Feng1‡, Eisuke Murakami1§, Chung K Chu2, Raymond F Schinazi3 and Karen S Anderson1* 1Department of Pharmacology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA 2Department of Pharmacology and Biomedical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, The University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA 3Laboratory of Biochemical Pharmacology, Emory University/Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Decatur, GA USA †Current address: Gilead Sciences Inc., Foster City, CA, USA ‡Current address: Gilead Sciences Inc., Durham, NC, USA §Current address: Pharmasset Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA *Corresponding author: Tel: +1 203 785 4526; Fax: +1 203 785 7670; E-mail: [email protected] Mitochondrial toxicity is a limiting factor in the use transcriptase showed CBV-TP to be approximately of some nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors 800–8,000-fold more selective for its antiviral target of HIV. To further understand the impact of struc- over pol γ relative to the other guanosine analogues. tural features on the incorporation and exonuclease However, DXG-TP and d4G-TP were found to be removal of nucleoside monophosphate (MP) much more selective than previously reported analogues by human mitochondrial DNA poly- values for mitochondrial toxic nucleoside analogues. merase (pol γ), transient kinetic studies were done Structural modelling based on sequence homology with analogues of 2′-deoxyguanosine triphosphate. with other polymerase A family members suggests The kinetic parameters for the incorporation and that an interaction between the ribose oxygen and removal of carbovir (CBV)-MP, dioxolane guanosine arginine 853 in pol γ may play a critical role in (DXG)-MP and 2′,3′-dideoxy-2′,3′-didehydroguano- causing this differential incorporation. -

Deoxyadenosine Triphosphate As a Mediator of Deoxyguanosine Toxicity in Cultured T Lymphoblasts

Deoxyadenosine triphosphate as a mediator of deoxyguanosine toxicity in cultured T lymphoblasts. G J Mann, R M Fox J Clin Invest. 1986;78(5):1261-1269. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI112710. Research Article The mechanism by which 2'-deoxyguanosine is toxic for lymphoid cells is relevant both to the severe cellular immune defect of inherited purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) deficiency and to attempts to exploit PNP inhibitors therapeutically. We have studied the cell cycle and biochemical effects of 2'-deoxyguanosine in human lymphoblasts using the PNP inhibitor 8-aminoguanosine. We show that cytostatic 2'-deoxyguanosine concentrations cause G1-phase arrest in PNP-inhibited T lymphoblasts, regardless of their hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase status. This effect is identical to that produced by 2'-deoxyadenosine in adenosine deaminase-inhibited T cells. 2'-Deoxyguanosine elevates both the 2'-deoxyguanosine-5'-triphosphate (dGTP) and 2'-deoxyadenosine-5'-triphosphate (dATP) pools; subsequently pyrimidine deoxyribonucleotide pools are depleted. The time course of these biochemical changes indicates that the onset of G1-phase arrest is related to increase of the dATP rather than the dGTP pool. When dGTP elevation is dissociated from dATP elevation by coincubation with 2'-deoxycytidine, dGTP does not by itself interrupt transit from the G1 to the S phase. It is proposed that dATP can mediate both 2'-deoxyguanosine and 2'-deoxyadenosine toxicity in T lymphoblasts. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/112710/pdf Deoxyadenosine Triphosphate as a Mediator of Deoxyguanosine Toxicity in Cultured T Lymphoblasts G. J. Mann and R. M. Fox Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (Sydney Branch), University ofSydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia Abstract urine of PNP-deficient individuals, with elevation of plasma inosine and guanosine and mild hypouricemia (3). -

Primer on Molecular Genetics

DOE Human Genome Program Primer on Molecular Genetics Date Published: June 1992 U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Research Office of Health and Environmental Research Washington, DC 20585 The "Primer on Molecular Genetics" is taken from the June 1992 DOE Human Genome 1991-92 Program Report. The primer is intended to be an introduction to basic principles of molecular genetics pertaining to the genome project. Human Genome Management Information System Oak Ridge National Laboratory 1060 Commerce Park Oak Ridge, TN 37830 Voice: 865/576-6669 Fax: 865/574-9888 E-mail: [email protected] 2 Contents Primer on Molecular Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 Genetics DNA............................................................................................................................... 6 Genes............................................................................................................................ 7 Revised and expanded Chromosomes ............................................................................................................... 8 by Denise Casey (HGMIS) from the Mapping and Sequencing the Human Genome ...................................... 10 primer contributed by Charles Cantor and Mapping Strategies ..................................................................................................... 11 Sylvia Spengler Genetic Linkage Maps ........................................................................................... -

Genetic Engineering Toward a 57-Codon Genome

Genetic Engineering Toward a 57-Codon Genome The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37944948 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2016 – Matthieu Landon All rights reserved Dissertation Advisor: George M. Church Matthieu Landon Abstract Scientific progress in fundamental biology has drastically transformed our ability to engineer biological systems, with diverse applications in medicine and industry, from insulin and artemisin production in prokaryotes to gene therapy in eukaryotes. In particular, DNA synthesis technologies and their recent plumetting cost have the potential to transform genome engineering by unlocking unlimited number of edits independent of the parent genome, paving the way for rational genome-wide changes. For example, a powerful strategy for enhancing genomes with functions not commonly found in nature is offered by recoding, the re-purposing of genetic codons. Indeed, since all living organisms share an identical genetic code composed of 64 genetic codons, changing this code allows exploration of new properties such as genetic isolation and expanded protein function. In that context, we set out to explore the feasibility of the construction of an entirely synthetic 57-codon genome in Escherichia coli. Construction of a 57-codon genome is a daunting task, due to the genome scale and to the unprecedented amount of DNA modifications to perform. -

Studies of the Genetic Encoding of Pyrrolysine From

STUDIES OF THE GENETIC ENCODING OF PYRROLYSINE FROM METHANOGENIC ARCHAEA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anirban Mahapatra, M.Sc. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Joseph A. Krzycki, Advisor Approved by Dr. Juan D. Alfonzo Dr. Charles J. Daniels Dr. Kurt L. Fredrick ___________________________ Advisor, Graduate Program in Microbiology ABSTRACT Pyrrolysine is the 22nd genetically encoded amino acid to be found in nature. Co-translational insertion at in-frame UAG codons proceeds so that a single pyrrolysine residue is found in the active site of all methylamine methyltransferases required for methylamine metabolism in Methanosarcina spp. This study examines processes central to the translation of UAG as pyrrolysine. The pylT gene encoding the tRNA for pyrrolysine, tRNAPyl, is part of the pyl operon of Methanosarcina spp. which also contains the pylS gene, encoding a class II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase; and the pylB, pylC, and pylD genes proposed to catalyze the synthesis of pyrrolysine from metabolic precursors. Here, in the first study, by characterizing a Methanosarcina acetivorans mutant with the pylT gene region deleted, the essentiality of pyrrolysine incorporation in methanogenesis from methylamines is tested. The mutant lacks detectable tRNAPyl but grows similar to wild-type on methanol or acetate for which translation of UAG as pyrrolysine is likely not to be essential. However, unlike wild-type, the mutant can not grow on any methylamine or use monomethylamine as the sole source of nitrogen. Monomethylamine methyltransferase activity is detectable in wild-type cells, but not in mutant cells during growth on methanol. -

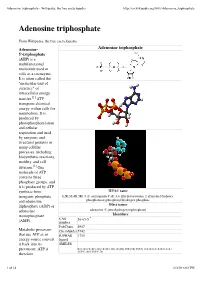

Adenosine Triphosphate - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Adenosine triphosphate - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adenosine_triphosphate Adenosine triphosphate From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Adenosine- Adenosine triphosphate 5'-triphosphate (ATP) is a multifunctional nucleotide used in cells as a coenzyme. It is often called the "molecular unit of currency" of intracellular energy transfer.[1] ATP transports chemical energy within cells for metabolism. It is produced by photophosphorylation and cellular respiration and used by enzymes and structural proteins in many cellular processes, including biosynthetic reactions, motility, and cell division.[2] One molecule of ATP contains three phosphate groups, and it is produced by ATP synthase from IUPAC name inorganic phosphate [(2R,3S,4R,5R)-5-(6-aminopurin-9-yl)-3,4-dihydroxyoxolan-2-yl]methyl(hydroxy- and adenosine phosphonooxyphosphoryl)hydrogen phosphate diphosphate (ADP) or Other names adenosine adenosine 5'-(tetrahydrogen triphosphate) monophosphate Identifiers CAS 56-65-5 (AMP). number PubChem 5957 Metabolic processes ChemSpider 5742 that use ATP as an IUPHAR 1713 energy source convert ligand it back into its SMILES precursors. ATP is O=P(O)(O)OP(=O)(O)OP(=O)(O)OC[C@H]3O[C@@H](n2cnc1c(ncnc12)N) [C@H](O)[C@@H]3O therefore 1 of 14 6/3/10 6:02 PM Adenosine triphosphate - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adenosine_triphosphate continuously recycled InChI in organisms: the 1/C10H16N5O13P3 human body, which /c11-8-5-9(13-2-12-8)15(3-14-5)10-7(17)6(16)4(26-10)1-25-30(21,22)28-31(23,24)27-29(18,19)20