Morality and Regionalism in the Novels of David Adams Richards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15962-4 — The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature This fully revised second edition of The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature offers a comprehensive introduction to major writers, genres, and topics. For this edition several chapters have been completely re-written to relect major developments in Canadian literature since 2004. Surveys of ic- tion, drama, and poetry are complemented by chapters on Aboriginal writ- ing, autobiography, literary criticism, writing by women, and the emergence of urban writing. Areas of research that have expanded since the irst edition include environmental concerns and questions of sexuality which are freshly explored across several different chapters. A substantial chapter on franco- phone writing is included. Authors such as Margaret Atwood, noted for her experiments in multiple literary genres, are given full consideration, as is the work of authors who have achieved major recognition, such as Alice Munro, recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature. Eva-Marie Kröller edited the Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature (irst edn., 2004) and, with Coral Ann Howells, the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (2009). She has published widely on travel writing and cultural semiotics, and won a Killam Research Prize as well as the Distin- guished Editor Award of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals for her work as editor of the journal Canadian -

Refractions of Germany in Canadian Literature and Culture

Refractions of Germany in Canadian Literature and Culture Edited by Hein2 Antor Sylvia Brown John Considine Klaus Stierstorfer Walter de Gruyter • Berlin • New York Contents Foreword V JOHN CONSIDINE, Introduction 1 ROBERT KROETSCH, Occupying Landscape We Occupy Story We Occupy Landscape 23 Diaspora and Settledness 31 SYLVIA BROWN, Voices From the Borderlands: The Problem of "Home" in the Oral Histories of German Expellees in Canada 33 ANNA WITTMANN, From Hungary to Germany to Canada: Gheorghiu's Twenty-Fifth Hour and Shifting Swabian Identities 57 PETER WEBB, Martin Blecher: Tom Thomson's Murderer or Victim of War- time Prejudice? 91 THOMAS MENGEL, Der deutsche Katholik in Kanada: An Approach to the Mentalite of German-speaking Catholics in Canada through an Analysis of their Journal 105 HEINZ ANTOR, The Mennonite Experience in the Novels of Rudy Wiebe ... 121 JOHN CONSIDINE, Dialectology, Storytelling, and Memory: Jack Thiessen's Mennonite Dictionaries 145 Jewish Experience and the Holocaust 169 AXEL STAHLER, The Black Forest, the Unspeakable Nefas, and the Mountains of Galilee: Germany and Zionism in the Works of A. M.Klein 171 VIII Contents KLAUS STIERSTORFER, Canadian Recontextualizations of a German Nightmare: Henry Kreisel's Betrayal (1964) 195 LAURENZ VOLKMANN, "Flowers for Hitler": Leonard Cohen's Holocaust Poetry in the Context of Jewish and Jewish-Canadian Literature .... 207 ALBERT-REINER GLAAP, Views on the Holocaust in Contemporary Canadian Plays . 239 Literature and Cultural Exchange 257 ANNETTE KERN-STAHLER, "The inability to mourn": the Post-war German Psyche in Mavis Gallant's Fiction 259 DORIS WOLF, Dividing and Reuniting Grandmothers, Mothers and Daughters: the Black Motherline, Vergangenheitsbewdltigung Studies, and the Road Genre in Suzette Mayr's The Widows . -

The Underpainter

Canadian Literature / Littérature canadienne A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Number 212, Spring 212 Published by The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Editor: Margery Fee Associate Editors: Judy Brown (Reviews), Joël Castonguay-Bélanger (Francophone Writing), Glenn Deer (Poetry), Laura Moss (Reviews) Past Editors: George Woodcock (1959–1977), W.H. New (1977–1995), Eva-Marie Kröller (1995–23), Laurie Ricou (23–27) Editorial Board Heinz Antor University of Cologne Alison Calder University of Manitoba Cecily Devereux University of Alberta Kristina Fagan University of Saskatchewan Janice Fiamengo University of Ottawa Carole Gerson Simon Fraser University Helen Gilbert University of London Susan Gingell University of Saskatchewan Faye Hammill University of Strathclyde Paul Hjartarson University of Alberta Coral Ann Howells University of Reading Smaro Kamboureli University of Guelph Jon Kertzer University of Calgary Ric Knowles University of Guelph Louise Ladouceur University of Alberta Patricia Merivale University of British Columbia Judit Molnár University of Debrecen Lianne Moyes Université de Montréal Maureen Moynagh St. Francis Xavier University Reingard Nischik University of Constance Ian Rae King’s University College Julie Rak University of Alberta Roxanne Rimstead Université de Sherbrooke Sherry Simon Concordia University Patricia Smart Carleton University David Staines University of Ottawa Cynthia Sugars University of Ottawa Neil ten Kortenaar University of Toronto Marie Vautier University of Victoria Gillian Whitlock University -

ENGL 3940-01 Struthers F21.Pdf

Preliminary Web Course Description *Please note: This is a preliminary web course description only. The department reserves the right to change without notice any information in this description. The final, binding course outline will be distributed in the first class of the semester. School of English and Theatre Studies Course Code: Course Title: Date of Offering: 3940*01 Seminar: Form, Genre & Literary Value Fall 2021 Topic for Sec. 01: Autobiography, Ficticity, Allegory Course Instructor: Course Format: Dr. J.R. (Tim) Struthers Asynchronous (For details, see end of this document) Brief Course Synopsis: Please Note: As needed, this Fall’s offering of ENGL*3940*01 (and ENGL*3940*02) may count as a .5 credit in “Canadian literature” if such a .5 credit is required in terms of specific “Distribution Requirements” for English Programs. The topic I have chosen for this course – “Autobiography, Ficticity, Allegory” -- and my personal desire to encourage a creative and a critical and a personal approach to reading and writing offer an opportunity to develop our understanding of traditionally distinct, now often merging art forms and theoretical approaches, of their values to ourselves and to others. As an important facet of this objective, members of this class should consider themselves not simply invited but strongly encouraged to reflect on and to explore the potential that the three different elements of “Autobiography; Ficticity; Allegory” contain for enhancing our thinking and writing in ways that give more scope to the individual imagination. Special attention will be given to ways in which these three elements combine in Indigenous writer (and Guelph resident) Thomas King’s book The Truth about Stories: A Native Narrative. -

Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury

1/13/2020 Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury Subscribe Past Issues Translate RS View this email in your browser Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury January 13, 2020 (Toronto, Ontario) – Elana Rabinovitch, Executive Director of the Scotiabank Giller Prize, today announced the five-member jury panel for the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize. This year marks the 27th anniversary of the Prize. The 2020 jury members are: Canadian authors David Chariandy, Eden Robinson and Mark Sakamoto (jury chair), British critic and Editor of the Culture segment of the Guardian, Claire Armitstead, and Canadian/British author and journalist, Tom Rachman. Some background on the 2020 jury: https://mailchi.mp/50144b114b18/introducing-the-2020-scotiabank-giller-prize-jury?e=a8793904cc 1/7 1/13/2020 Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury Subscribe Past Issues Translate RS Claire Armitstead is Associate Editor, Culture, at the Guardian, where she has previously acted as arts editor, literary editor and head of books. She presents the weekly Guardian books podcast and is a regular commentator on radio, and at live events across the UK and internationally. She is a trustee of English PEN. David Chariandy is a writer and critic. His first novel, Soucouyant, was nominated for 11 literary prizes, including the Governor General’s Award and the Scotiabank https://mailchi.mp/50144b114b18/introducing-the-2020-scotiabank-giller-prize-jury?e=a8793904cc 2/7 1/13/2020 Introducing the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury Brother Subscribe GillerPast Prize. His Issues second novel, , was nominated for fourteen prizes, winningTranslate RS the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, and the Toronto Book Award. -

A. Scholarships

A. Scholarships St. Thomas University recognizes academic excellence through a generous scholarship program. The university offers a wide range of entrance awards to highly qualified students admitted on the basis of their high school records, as well as numerous scholarships-in- course to continuing students who have achieved academic distinction at St. Thomas. Entrance Scholarships The Entrance Scholarship program is competitive and is designed to attract outstand- ing scholars to the St. Thomas University campus. Except when otherwise specified, the entrance awards are open to candidates for full-time admission to the first year of the Bachelor of Arts program who are applying on the basis of their high school records. 1. Selection Criteria In selecting entrance scholarship recipients, the primary criterion considered by the Entrance Scholarship Selection Committee is the academic record. The Committee reviews the following: • admission average • Grade 12 program: courses and levels • rank in graduating class • program and performance in grade 11 Note: The admission average is calculated on the senior-level academic English grade and the grades on four other Grade 12 academic courses drawn from our list of approved admis- sions subjects. For details, please consult Section One, Admissions and Registration. At mid year, the admission averages for scholarship purposes is calculated on the overall av- erage of final grades on Grade 11 academic subjects, as well as final first-semester results or mid-year results (for non-semestered schools) on Grade 12 academic subjects. Other factors considered include: • a reference letter from a teacher, principal or guidance counsellor In addition to the academic selection criteria, the following criteria are considered in award- ing some entrance scholarships: • leadership qualities • extracurricular activities • financial status 2. -

MS ATWOOD, Margaret Papers Coll

MS ATWOOD, Margaret Papers Coll. 00127L Gift of Margaret Atwood, 2017 Extent: 36 boxes and items (11 metres) Includes extensive family and personal correspondence, 1940s to the present; The Handmaid’s Tale TV series media; Alias Grace TV series media; The Heart Goes Last dead matter; appearances; print; juvenilia including papier mache puppets made in high school; Maternal Aunt Joyce Barkhouse (author of Pit Pony and Anna’s Pet), fan mail; professional correspondence and other material Arrangement note: correspondence was organized in various packets and has been kept in original order, rather than alphabetical or chronological order Restriction note: Puppets are restricted due to their fragility (Boxes 26-29). Box 1 Family correspondence, 1970s-1980s: 95 folders Parents (Carl and Margaret Eleanor Atwood) Aunt Kae Cogswell Aunt Ada Folder 1 Mother to Peggy and Jim ALS and envelope January 2, 1969 [sic] 1970 Folder 2 Mother to Peggy and Jim ALS and envelope March 30, 1970 Folder 3 Mother to Peggy and Jim TLS and envelope April 21, 1970 Folder 4 Mother to Peggy and Jim TLS and ALS, envelope April 29, 1970 Folder 5 Mother to Peggy and Jim ALS August 20, 1970 Folder 6 Mother to Peggy and Jim ALS September 6, 1970 Folder 7 Mother to Peggy and Jim TLS, ANS and envelope September 17, 1970 1 MS ATWOOD, Margaret Papers Coll. 00127L Folder 8 Mother to Peggy ALS September 19, 1970 Folder 9 Dad to Peggy ALS September 26, 1970 Folder 10 Mother to Peggy and Jim TLS (stamps) and envelope October 14, 1970 Folder 11 Mother to Peggy and Jim ALS November 10, 1970 Folder 12 Mother to Peggy ALS November 15, 1970 Folder 13 Mother to Peggy and Jim ALS December 20, 1970 Folder 14 Mother to Peggy and Jim TLS and envelope December 27, 1970 Folder 15 Mother to Peggy and Jim TLS and envelope January 8, 1971 Folder 16 Mother to Peggy and Jim TLS and envelope January 15, 1971 Folder 17 Mother to Peggy and Jim TLS January 20, 1971 TLS and envelope January 27, 1971 Folder 18 Mother to Peggy ALS and envelope November 25, 1973 2 MS ATWOOD, Margaret Papers Coll. -

General Fiction

GENERAL FICTION A Aciman, Andre – Enigma variations Ackerman, Marianne - Jump Addison, Corban – Garden of burning sand/Tears of dark water Ahlborn, Ania – Apart in the dark Akpan, Uwem – Say you’re one of the them Alarcon, Daniel – At night we walked in circles Albom, Mitch –First phone call from heaven/For one more day/Next person you meet in heaven Allende, Isabel – Daughter of fortune Anderson-Dargatz, Gail – Cure for death by lightning Andrews, Mary Kay –Ladies’ night Ansay, A. Manette – Vinegar Hill Arsenault, Emily –Evening spider Ashley, Phillipa – Cornish Café Series: Spring on the Little Cornish Isles Aslam, Nadeem – Maps for lost lovers Atkinson, Kate –Not the end of the world/Transcription/Started early, took my dog Atwood, Margaret –Oryx and crake/Edible woman/Alias Grace/Blind assassin/Cats eye/Madd Addam Awad, Mona – 13 ways of looking at a fat girl B Backman, Fredrik – Bear Town Baker Kline, Christina – Orphan train/Piece of the world Baker, Shannon – Stripped bare Bala, Sharon – Boat people Banville, John – Mrs Osmond Barbery, Muriel – Elegance of the hedgehog Barclay, Robert – If wishes were horses Barnes, Julian – Sense of an ending Barry, Sebastian – On Canaan’s side Beatty, Paul – Sellout Behrens, Peter – Travelling light/Law of dreams Delinsky, Barbara – Not my daughter Benedict, Marie – Carneigies’ maid Bergen, David – Retreat/Leaving tomorrow Blume, Judy – In the unlikely event Boyden, Joseph – The Orenda/Through black spruce Brackston, Paula – Lamp black, wolf grey Brashares, Ann – My name is memory Britton, Fern – Hidden treasures Brodber, Erna - Myal Brooks, Geraldine – People of the book Buckley, Carla – Deepest secret Burnard, Bonnie – Good house Bushnell, Candace – Carrie Diaries: Summer and the city Byler, Linda – Sadie’s Montana: Bk2 Keeping secrets C Caletti, Deb – Secrets she keeps Callahan Henry, Patti – And then I found you Cameron, W. -

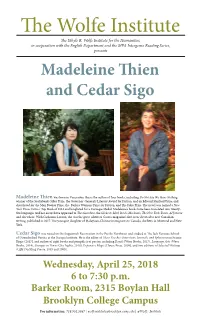

The Wolfe Institute the Ethyle R

The Wolfe Institute The Ethyle R. Wolfe Institute for the Humanities, in cooperation with the English Department and the MFA Intergenre Reading Series, presents Madeleine Thien and Cedar Sigo Madeleine Thien was born in Vancouver. She is the author of four books, including Do Not Say We Have Nothing, winner of the Scotiabank Giller Prize, the Governor-General’s Literary Award for Fiction, and an Edward Stanford Prize; and shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction, and The Folio Prize. The novel was named a New York Times Critics’ Top Book of 2016 and longlisted for a Carnegie Medal. Madeleine’s books have been translated into twenty- five languages and her essays have appeared in The Guardian, the Globe & Mail, Brick, Maclean’s, The New York Times, Al Jazeera and elsewhere. With Catherine Leroux, she was the guest editor of Granta magazine’s first issue devoted to new Canadian writing, published in 2017. The youngest daughter of Malaysian-Chinese immigrants to Canada, she lives in Montreal and New York. Cedar Sigo was raised on the Suquamish Reservation in the Pacific Northwest and studied at The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at the Naropa Institute. He is the editor of There You Are: Interviews, Journals, and Ephemera on Joanne Kyger (2017), and author of eight books and pamphlets of poetry, including Royals (Wave Books, 2017), Language Arts (Wave Books, 2014), Stranger in Town (City Lights, 2010), Expensive Magic (House Press, 2008), and two editions of Selected Writings (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2003 and 2005). Wednesday, April 25, 2018 6 to 7:30 p.m. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Permission) National Library Bibfaotheque nationale 1+1 of Canada duCanada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a Ia National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distn'bute or sell reproduire, preter, distri'buer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format electronique. The author retains ownership of the L' auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permiSSIOn. autorisation. 0-612-25875-0 Canadrl INFORMATION TO USERS This mamJSCript Jlas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the origiDal or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in eypewriter face., while others may be from any twe of a:nnputer printer. 'l1le qaJily or dais nprodadioa is depelldellt apoa tile quality or the copy sahwiUed Broken or iDdistinct print. colored or poor quality iJlustratioDs aDd photograpbs, prim bleedtbrougb, substaDdard margiDs, and improper alignmeut can adversely affect reproduc:tioa. -

MARGARET ATWOOD: WRITING and SUBJECTIVITY Also by Colin Nicholson

MARGARET ATWOOD: WRITING AND SUBJECTIVITY Also by Colin Nicholson POEM, PURPOSE, PLACE: Shaping Identity in Contemporary Scottish Verse ALEXANDER POPE: Essays for the Tercentenary (editor) CRITICAL APPROACHES TO THE FICTION OF MARGARET LAURENCE (editor) IAN CRICHTON SMITH: New Critical Essays (editor) Margaret Atwood photo credit: Graeme Gibson Margaret Atwood: Writing and Subjectivity New Critical Essays Edited by Colin Nicholson Senior Lecturer in English University of Edinburgh M St. Martin's Press Editorial material and selection © Colin Nicholson 1994 Text © The Macmillan Press Ltd 1994 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 9HE. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published in Great Britain 1994 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-333-61181-4 ISBN 978-1-349-23282-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-23282-6 First published in the United States of America 1994 by Scholarly and Reference Division, ST. MARTIN'S PRESS, INC., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 ISBN 978-0-312-10644-7 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Margaret Atwood : writing and subjectivity I edited by Colin Nicholson.