World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Baltic Republics

FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1994 Finnish Defence Studies is published under the auspices of the National Defence College, and the contributions reflect the fields of research and teaching of the College. Finnish Defence Studies will occasionally feature documentation on Finnish Security Policy. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily imply endorsement by the National Defence College. Editor: Kalevi Ruhala Editorial Assistant: Matti Hongisto Editorial Board: Chairman Prof. Mikko Viitasalo, National Defence College Dr. Pauli Järvenpää, Ministry of Defence Col. Antti Numminen, General Headquarters Dr., Lt.Col. (ret.) Pekka Visuri, Finnish Institute of International Affairs Dr. Matti Vuorio, Scientific Committee for National Defence Published by NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE P.O. Box 266 FIN - 00171 Helsinki FINLAND FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES 6 THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1992 ISBN 951-25-0709-9 ISSN 0788-5571 © Copyright 1994: National Defence College All rights reserved Painatuskeskus Oy Pasilan pikapaino Helsinki 1994 Preface Until the end of the First World War, the Baltic region was understood as a geographical area comprising the coastal strip of the Baltic Sea from the Gulf of Danzig to the Gulf of Finland. In the years between the two World Wars the concept became more political in nature: after Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania obtained their independence in 1918 the region gradually became understood as the geographical entity made up of these three republics. Although the Baltic region is geographically fairly homogeneous, each of the newly restored republics possesses unique geographical and strategic features. -

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

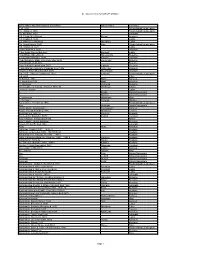

All Latvia Cemetery List-Final-By First Name#2

All Latvia Cemetery List by First Name Given Name and Grave Marker Information Family Name Cemetery ? d. 1904 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Itshak d. 1863 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? b. Abraham 1900 Jekabpils ? B. Chaim Meir Potash Potash Kraslava ? B. Eliazar d. 5632 Ludza ? B. Haim Zev Shuvakov Shuvakov Ludza ? b. Itshak Katz d. 1850 Katz Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? B. Shalom d. 5634 Ludza ? bar Abraham d. 5662 Varaklani ? Bar David Shmuel Bombart Bombart Ludza ? bar Efraim Shmethovits Shmethovits Rezekne ? Bar Haim Kafman d. 5680 Kafman Varaklani ? bar Menahem Mane Zomerman died 5693 Zomerman Rezekne ? bar Menahem Mendel Rezekne ? bar Yehuda Lapinski died 5677 Lapinski Rezekne ? Bat Abraham Telts wife of Lipman Liver 1906 Telts Liver Kraslava ? bat ben Tzion Shvarbrand d. 5674 Shvarbrand Varaklani ? d. 1875 Pinchus Judelson d. 1923 Judelson Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava ? d. 5608 Pilten ?? Bloch d. 1931 Bloch Karsava ?? Nagli died 5679 Nagli Rezekne ?? Vechman Vechman Rezekne ??? daughter of Yehuda Hirshman 7870-30 Hirshman Saldus ?meret b. Eliazar Ludza A. Broido Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Blostein Dvinsk/Daugavpils A. Hirschman Hirschman Rīga A. Perlman Perlman Windau Aaron Zev b. Yehiskiel d. 1910 Friedrichstadt/Jaunjelgava Aba Ostrinsky Dvinsk/Daugavpils Aba b. Moshe Skorobogat? Skorobogat? Karsava Aba b. Yehuda Hirshberg 1916 Hirshberg Tukums Aba Koblentz 1891-30 Koblentz Krustpils Aba Leib bar Ziskind d. 5678 Ziskind Varaklani Aba Yehuda b. Shrago died 1880 Riebini Aba Yehuda Leib bar Abraham Rezekne Abarihel?? bar Eli died 1866 Jekabpils Abay Abay Kraslava Abba bar Jehuda 1925? 1890-22 Krustpils Abba bar Jehuda died 1925 film#1890-23 Krustpils Abba Haim ben Yehuda Leib 1885 1886-1 Krustpils Abba Jehuda bar Mordehaj Hakohen 1899? 1890-9 hacohen Krustpils Abba Ravdin 1889-32 Ravdin Krustpils Abe bar Josef Kaitzner 1960 1883-1 Kaitzner Krustpils Abe bat Feivish Shpungin d. -

Circular Economy and Bioeconomy Interaction Development As Future for Rural Regions. Case Study of Aizkraukle Region in Latvia

Environmental and Climate Technologies 2019, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 129–146 doi: 10.2478/rtuect-2019-0084 https://content.sciendo.com Circular Economy and Bioeconomy Interaction Development as Future for Rural Regions. Case Study of Aizkraukle Region in Latvia Indra MUIZNIECE1*, Lauma ZIHARE2, Jelena PUBULE3, Dagnija BLUMBERGA4 1–4Institute of Energy Systems and Environment, Riga Technical University, Azenes iela 12/1, Riga, LV-1048, Latvia Abstract – In order to enforce the concepts of bioeconomy and the circular economy, the use of a bottom-up approach at the national level has been proposed: to start at the level of a small region, encourage its development, considering its specific capacities and resources, rather than applying generalized assumptions at a national or international level. Therefore, this study has been carried out with an aim to develop a methodology for the assessment of small rural areas in the context of the circular economy and bioeconomy, in order to advance the development of these regions in an effective way, using the existing bioresources comprehensively. The methodology is based on the identification of existing and potential bioeconomy flows (land and its use, bioresources, human resources, employment and business), the identification of the strengths of their interaction and compare these with the situation at the regional and national levels in order to identify the specific region's current situation in the bioeconomy and identify more forward-looking directions for development. Several methods are integrated and interlinked in the methodology – indicator analysis, correlation and regression analysis, and heat map tables. The methodology is approbated on one case study – Aizkraukle region – a small rural region in Latvia. -

CSDD 2018/29 ERAF 3.Pielikums CSDD Rīkotā Iepirkuma Nolikumam

CSDD 2018/29 ERAF 3.pielikums CSDD rīkotā iepirkuma nolikumam STACIJAS atrašanās vietas shēma Adrese: Rīgas iela 4, Aloja, Alojas nov., LV-4064 Nekustamā īpašuma kadastra apzīmējums: 66070030032 1 CSDD 2018/29 ERAF STACIJAS atrašanās vietas shēma Adrese: Raiņa iela 4, Auce, Auces nov., LV-3708 Nekustamā īpašuma kadastra apzīmējums: 46050090910 2 CSDD 2018/29 ERAF STACIJAS atrašanās vietas shēma Adrese: Zvaigžņu iela 2A, Aizpute, Aizputes nov., LV-3456 Nekustamā īpašuma kadastra apzīmējums: 64050070090 3 CSDD 2018/29 ERAF STACIJAS atrašanās vietas shēma Adrese: Dārza iela 25A, Bērzpils, Bērzpils pag., Balvu nov., LV-4576 Nekustamā īpašuma kadastra apzīmējums: 38500020281 4 CSDD 2018/29 ERAF STACIJAS atrašanās vietas shēma Nosaukums: "Automašīnu stāvlaukums pie baznīcas", Dundagas pagasts, Dundagas novads Nekustamā īpašuma kadastra apzīmējums: 88500200209 5 CSDD 2018/29 ERAF STACIJAS atrašanās vietas shēma Adrese: Lāčplēša iela 11, Jaunjelgava, Jaunjelgavas nov., LV-5134 Nekustamā īpašuma kadastra apzīmējums: 32070020388 6 CSDD 2018/29 ERAF STACIJAS atrašanās vietas shēma Nosaukums: "5.noliktavas caurlaide", Kolkas pagasts, Dundagas novads Nekustamā īpašuma kadastra apzīmējums: 88620070260 7 CSDD 2018/29 ERAF STACIJAS atrašanās vietas shēma Nosaukums: "Pils iela 8B", Mālpils novads Nekustamā īpašuma kadastra apzīmējums: 80740030845 8 CSDD 2018/29 ERAF STACIJAS atrašanās vietas shēma Adrese: Rīgas iela 26B, Vecumnieki, Vecumnieku pag., Vecumnieku nov., LV-3933 Nekustamā īpašuma kadastra apzīmējums: 40940120980 9 CSDD 2018/29 ERAF STACIJAS -

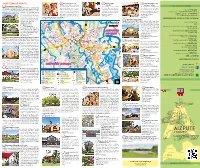

Sightseeing in Aizpute

SIGHTSEEING IN AIZPUTE 9 Valda Jēriņa Dolls room 14 Weavers’ Studio 20 Centre of workshops and The exposition shows a collection “Kamolītis” residences “SERDE” WWW.VISITAIZPUTE.LV 1 Livonian Order Castle Ruins of dolls created by national theatre The workshop offers its visitors This set of historical buildings, with th The Livonian Order built the fortifications in the 13 century. In the actress Valda Jēriņa. There are more to see the process of different its creative ambience, welcomes – 113, 112 113, – Ambulance th 15 century, a residential house was built at its eastern wall, with than 500 thematically dressed dolls canvas being woven in the looms you to enjoy a variety of cultural – (+371) 26475143 (+371) – police municipal county Aizpute cellars and a gallery; thus the fortifications were turned into a castle. in the collection: dolls in national according to ancient methods tourism opportunities, art and – 110, 112, (+371) 63448192 (+371) 112, 110, – It served as a border fortification at police State costumes, school uniforms, theatrical and using traditional ornaments. cultural events (open in summer). the cross point of the territories of – 112 – and fantasy costumes. There is a Katoļu iela 1, Aizpute, Atmodas iela 9, Aizpute, departament Rescue and Fire the Livonian Order and the Bishop children’s playroom next to the (+371) 22847115 (+371) 29817180, of Courland (Latvian: Kurzeme). exhibition halls. Book your visit in advance. www.serde.lv EMERGENCY OF CASES IN CALL TO WHERE The river Tebra was the border: the Katoļu iela 1, Aizpute, (+371) 28617307 Bishopric on the right bank and the 21 “IDEJU MĀJA” (IDEA HOUSE) (+371) 25125190 (+371) Phone: Livonian Order on the left. -

As Parex Banka

AS PAREX BANKA ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2008 TOGETHER WITH INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT Table of Contents Management Report 3 Management of the Bank 7 Statement of Responsibility of the Management 8 Financial Statements: Statements of Income 9 Balance Sheets 10 Statements of Changes in Equity 11 Statements of Cash Flows 13 Notes 14 Auditors’ Report 80 AS Parex banka Smilšu 3, Riga, LV-1522, Latvia Phone: (371) 67010 000 Facsimile: (371) 67010 001 Registration number: 40003074590 2 AS Parex banka Management Report The year 2008 brought major change to Parex banka , including substantial changes in shareholders structure and the management of the bank in the last months of 2008. This report has been prepared by the new Management Board and Supervisory Council of the Bank and they are committed to leading the Bank into a new phase of development. Financial crisis and its implications on Parex banka The year of 2008 brought unprecedented challenges for the financial sector both in Latvia and worldwide. The global credit crunch, starting in the United States of America, caused a chain reaction all over the world and intensified the economic difficulties in Latvia. The financial sector in Latvia has been affected in a number of ways, mostly through reduced availability of funding and liquidity from international financial markets, a weakening economy and the resulting decline of asset quality. The crisis has necessitated the adoption of new approaches to the financial sector and has led to a thorough reconsideration of its practices. Parex banka itself experienced a severe impact from the crisis of 2008. -

Enforcement of Scc and Russian Arbitration Awards in the United States Courts: an Overview

Stockholm Arbitration Report, Volume 2003:2 ENFORCEMENT OF SCC AND RUSSIAN ARBITRATION AWARDS IN THE UNITED STATES COURTS: AN OVERVIEW Alexander S. Vesselinovitch* Several published decisions by U.S. federal and state courts have addressed SCC and Russian arbitration awards and proceedings. Some of these decisions, which came after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, strongly suggest that a Russian arbitration award will be enforced against a U.S. party or citizen by a U.S. court. Moreover, the published decisions by U.S. courts lend support to the enforcement by a U.S. court of an arbitration award rendered by the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (“SCC”) against a U.S. party. 1. Policy of New York Convention Favors Enforcement The Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards of 1958, commonly called the “New York Convention,” was adopted with several reservations by the United States in 1970. The enabling legislation incorporated the New York Convention into Chapter Two of the United States Federal Arbitration Act, 9 U.S.C. §§ 201-208. * Katten Muchin Zavis Rosenman, 525 West Monroe Street, Suite 1600, Chicago, Illinois 60661, (Telephone) 312-902-5660, (Facsimile) 312-577-4755, E-Mail: [email protected]. © 2003 Juris Publishing, Inc. Reprinted with Permission. All rights reserved. 37 Sweden, Russia, and the United States are signatories and contracting parties to the New York Convention. Moreover, Russian courts have applied provisions of the New York Convention under Russia’s Civil Code. Several commentators have already observed that the prospects for the enforcement of an SCC Institute award are very favorable in the courts of another party to the New York Convention.1 Because Sweden has generous rules regarding the validity of arbitration agreements, an arbitral award rendered on the basis of such an agreement will rarely be refused enforcement.2 Nevertheless, no published decision by a U.S. -

The Global Financial Crisis: Analysis and Policy Implications

The Global Financial Crisis: Analysis and Policy Implications Dick K. Nanto, Coordinator Specialist in Industry and Trade July 2, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34742 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Global Financial Crisis: Analysis and Policy Implications Summary The world has entered a global recession that is causing widespread business contraction, increases in unemployment, and shrinking government revenues. Some of the largest and most venerable banks, investment houses, and insurance companies have either declared bankruptcy or have had to be rescued financially. Nearly all industrialized countries and many emerging and developing nations have announced economic stimulus and/or financial sector rescue packages, such as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5). Several countries have resorted to borrowing from the International Monetary Fund as a last resort. The crisis has exposed fundamental weaknesses in financial systems worldwide, demonstrated how interconnected and interdependent economies are today, and has posed vexing policy dilemmas. The process for coping with the crisis by countries across the globe has been manifest in four basic phases. The first has been intervention to contain the contagion and restore confidence in the system. This has required extraordinary measures both in scope, cost, and extent of government reach. The second has been coping with the secondary effects of the crisis, particularly the global recession and flight of capital from countries in emerging markets and elsewhere that have been affected by the crisis. The third phase of this process is to make changes in the financial system to reduce risk and prevent future crises. -

The Saeima (Parliament) Election

/pub/public/30067.html Legislation / The Saeima Election Law Unofficial translation Modified by amendments adopted till 14 July 2014 As in force on 19 July 2014 The Saeima has adopted and the President of State has proclaimed the following law: The Saeima Election Law Chapter I GENERAL PROVISIONS 1. Citizens of Latvia who have reached the age of 18 by election day have the right to vote. (As amended by the 6 February 2014 Law) 2.(Deleted by the 6 February 2014 Law). 3. A person has the right to vote in any constituency. 4. Any citizen of Latvia who has reached the age of 21 before election day may be elected to the Saeima unless one or more of the restrictions specified in Article 5 of this Law apply. 5. Persons are not to be included in the lists of candidates and are not eligible to be elected to the Saeima if they: 1) have been placed under statutory trusteeship by the court; 2) are serving a court sentence in a penitentiary; 3) have been convicted of an intentionally committed criminal offence except in cases when persons have been rehabilitated or their conviction has been expunged or vacated; 4) have committed a criminal offence set forth in the Criminal Law in a state of mental incapacity or a state of diminished mental capacity or who, after committing a criminal offence, have developed a mental disorder and thus are incapable of taking or controlling a conscious action and as a result have been subjected to compulsory medical measures, or whose cases have been dismissed without applying such compulsory medical measures; 5) belong -

Plūdu Riska Novērtēšanas Un Pārvaldības Nacionālā Programma 2008.-2015.Gadam

Approved by Cabinet Order No.830 20 December 2007 National Programme for the Assessment and Management of Flood Risks 2008 - 2015 Informative Part Riga 2007 Translation © 2013 Valsts valodas centrs (State Language Centre) Contents Abbreviations Used 3 Terms used in the Programme 3 I. Characterisation of the Situation 4 1. Assessment of the Territory of Latvia in Respect of Flood Risks 7 1.1. Types of Flood Risk Areas in the Territory of Latvia 7 1.2. Causes of Floods in Flood Risk Areas 8 1.3. Areas Being Flooded Due to Floods and Areas at Risk of Flooding 9 1.4. Specially Protected Nature Territories 12 1.5. Historical Consequences and Material Losses of Floods 12 2. Flood Risk Scenarios and Assessment Criteria Thereof 13 II. Link of the Programme to the Priorities and Supporting Policy Documents of the Government and Ministries 15 III. Objectives and Sub-objectives of the Programme 17 IV. Planned Results of the Programme Policy and Results of the Activity 17 V. The Result-based Indicators for the Achievement of Results of the Programme Policy and Results of Activity 18 VI. Main Tasks for the Achievement of Results of the Programme 18 VII Programme Funding 18 Annexes 1. Annex 1 River Basin Districts of Latvia 20 2. Annex 2 Flood Risk Areas in River Potamal Sections 21 3. Annex 3 Coastal Flood Risk and Coastal Erosion Risk Areas of the Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Riga 25 4. Annex 4 Measures for the Assessment and Reduction of Flood Risks 26 Translation © 2013 Valsts valodas centrs (State Language Centre) 2 Abbreviations Used MoE – Ministry of Economics MoF – Ministry of Finance MoENV – Ministry of Environment MoA – Ministry of Agriculture EU – European Union HPS – Hydroelectric power station UNECE – United Nations Economic Commission for Europe a/g - agriculture mBs – metres in the Baltic system ha - hectare Terms Used in the Programme Flood – the covering by water of land not normally covered by water. -

The Baltics EU/Schengen Zone Baltic Tourist Map Traveling Between

The Baltics Development Fund Development EU/Schengen Zone Regional European European in your future your in g Investin n Unio European Lithuanian State Department of Tourism under the Ministry of Economy, 2019 Economy, of Ministry the under Tourism of Department State Lithuanian Tampere Investment and Development Agency of Latvia, of Agency Development and Investment Pori © Estonian Tourist Board / Enterprise Estonia, Enterprise / Board Tourist Estonian © FINL AND Vyborg Turku HELSINKI Estonia Latvia Lithuania Gulf of Finland St. Petersburg Estonia is just a little bigger than Denmark, Switzerland or the Latvia is best known for is Art Nouveau. The cultural and historic From Vilnius and its mysterious Baroque longing to Kaunas renowned Netherlands. Culturally, it is located at the crossroads of Northern, heritage of Latvian architecture spans many centuries, from authentic for its modernist buildings, from Trakai dating back to glorious Western and Eastern Europe. The first signs of human habitation in rural homesteads to unique samples of wooden architecture, to medieval Lithuania to the only port city Klaipėda and the Curonian TALLINN Novgorod Estonia trace back for nearly 10,000 years, which means Estonians luxurious palaces and manors, churches, and impressive Art Nouveau Spit – every place of Lithuania stands out for its unique way of Orebro STOCKHOLM Lake Peipus have been living continuously in one area for a longer period than buildings. Capital city Riga alone is home to over 700 buildings built in rendering the colorful nature and history of the country. Rivers and lakes of pure spring waters, forests of countless shades of green, many other nations in Europe.