COPYRIGHT and CITATION CONSIDERATIONS for THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION O Attribution — You Must Give Appropriate Credit, Provide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01 Cover 177 Donkerder 01

01_Cover 177 donkerder_01 21-04-11 13:32 Pagina 1 28e jaargang, april 2o11 nummer 177177 www.devoetbaltrainer.nl Trainer Trainer Voetbal Han Berger Technisch Directeur Australische voetbalbond Patrick van Leeuwen Hoofd Opleidingen Shakhtar Donetsk De De Willem den Besten Succestrainer bij XerxesDZB VBT 177-2011_Trainerscongres_1-1_0 21-04-11 12:19 Pagina 1 ZATERDAG 28 MEI 2011 VAN 9:00 UUR TOT 16:30 UUR WILLEM II STADION, TILBURG Als abonnee van De VoetbalTrainer betaalt u slechts € 45,- ipv € 65,- klik SCHRIJF U NU IN VOOR DE 9E EDITIE VAN HET NEDERLANDS op TRAINERSCONGRES VIA: INSCHRIJVEN WWW.TRAINERSCONGRES.NL IN SAMENWERKING MET DE VVON EN DE VOETBALTRAINER ORGANISEERT DE CBV OP ZATERDAG 28 MEI HET NEDERLANDSE TRAINERSCONGRES. THEMA VAN DEZE 9E EDITIE IS “SAMEN@WORK”. PROGRAMMA 9:00 – 9:45 uur Ontvangst 9:45 uur Opening 10:00 – 10:40 uur Jeugditem: Feyenoord – Stanley Brard, hoofd jeugdacademie Feyenoord 10:50 – 11:30 uur Keeperstraining: Edwin Susebeek, keeperstrainer PSV 11:45 – 12:15 uur Deel 1: Workshop -Lunch 12:25 – 12:55 uur Deel 2: Workshop - Lunch 13:05 – 13:35 uur Deel 3: Workshop - Lunch Workshops: - Individueel talentvolgsysteem: Talenttree Wiljan Vloet - Ervaringen in de Topklasse: Niek Oosterlee, Rijnsburgse Boys 13:45 – 14:30 uur Uitreiking Rinus Michels Awards, Presentatie: Toine van Peperstraten 14:45 – 15:45 uur Topcoach: John van den Brom, ADO Den Haag 16:00 uur Dankwoord en uitreiking certificaten (studiepunten) DeVoetbalTrainer devoetbaltrainer.nl 03_Inhoud-redactie_03 21-04-11 13:33 Pagina 3 In dit nummer Van de redactie Tijdens het gesprek met de hoofdpersoon uit ons ope- ningsartikel, Han Berger, kwam een door hem gelezen Van de lange bal naar het korte spel 4 en zeer gewaardeerd boek ter sprake. -

AA-Postscript.Qxp:Layout 1

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 2014 SPORTS What did the WCup do for you, Bafana? CAPE TOWN: In two or 10, or even 20 years’ time State Stadium on their way to beating former The same five African teams that made the a visitor to South Africa might turn to a football world champion France. A dysfunctional France last World Cup - Ivory Coast, Ghana, Nigeria, fan and ask: “So, what did that 2010 World Cup do team, maybe, but South Africa also almost beat Cameroon and Algeria - qualified again. South for you?” Mexico in an exhilarating opening game. No one Africa, with no hosting rights to save it this time, The South African, with vuvuzela (remember doubted the hosts belonged at the World Cup. couldn’t even win a place in Africa’s 10-team final them?) gripped proudly in one hand, could cite Now, South Africa is nowhere - not even World Cup playoffs, beaten out by Ethiopia, no increased investment in the country. He or she among the 31 teams that qualified for this year’s less. could maybe say there are more tourists coming World Cup in Brazil. Well, not exactly nowhere. It is The last time South Africa qualified for a major than ever before. And, with a satisfied blast on the on FIFA’s radar for an investigation into match-fix- tournament it didn’t host was 2008. It only vuvuzela point out that South Africa has the best ing allegations. And it is still in the news at home - returned to the African Cup in 2013 because no one else could fill in for troubled Libya at a moment’s notice. -

An Anthropological Study Into the Lives of Elite Athletes After Competitive Sport

After the triumph: an anthropological study into the lives of elite athletes after competitive sport Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements in respect of the Doctoral Degree in Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of the Free State Supervisor: Professor Robert Gordon December 2015 DECLARATION I, Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh, declare that the thesis that I herewith submit for the Doctoral Degree of Philosophy at the University of the Free State is my independent work, and that I have not previously submitted it for a qualification at another institution of higher education. I, Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh, hereby declare that I am aware that the copyright is vested in the University of the Free State. I, Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh, hereby declare that all royalties as regards intellectual property that was developed during the course of and/or in connection with the study at the University of the Free State, will accrue to the University. In the event of a written agreement between the University and the student, the written agreement must be submitted in lieu of the declaration by the student. I, Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh, hereby declare that I am aware that the research may only be published with the dean’s approval. Signed: Date: December 2015 ii ABSTRACT The decision to retire from competitive sport is an inevitable aspect of any professional sportsperson’s career. This thesis explores the afterlife of former professional rugby players and athletes (road running and track) and is situated within the emerging sub-discipline of the anthropology of sport. -

Here Is No Shortage of Dangerous-Looking Designated Hosts Morocco Were So Concerned That They Teams in the Competition

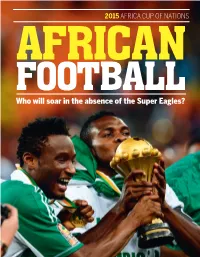

2015 AFRICA CUP OF NATIONS AFRICAN FOOT BALL Who will soar in the absence of the Super Eagles? NA0115.indb 81 13/12/2014 08:32 Edited and compiled by Colin Udoh Fears, tears and cheers n previous years, club versus country disputes have Ebebiyín might be even more troubling. It is even tended to dominate the headlines in the run-up to more remote than Mongomo, and does not seem to Africa Cup of Nations tournaments. The stories are have an airport nearby. The venue meanwhile can hold typically of European clubs, unhappy about losing just 5,000 spectators, a fraction of the 35,000 that the their African talent for two to three weeks in the national stadium in Bata can accommodate. middle of the season, pulling out all the stops in a Teams hoping to win the AFCON title will have to Ibid to hold on to their players. negotiate far more than just some transport problems. This time, however, the controversy centred on a much After all, although Nigeria and Egypt surprisingly failed more serious issue: Ebola. Whether rightly or wrongly, the to qualify, there is no shortage of dangerous-looking designated hosts Morocco were so concerned that they teams in the competition. The embarrassment of talent requested a postponement, then withdrew outright when enjoyed by the likes of Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Algeria the Confederation of African Football (CAF) turned will fill their opponents with fear, while so many of the down their request. teams once considered Africa’s minnows have grown in That is the reason Equatorial Guinea, who had been stature and quality in recent years. -

Africa Cup of Nations 2013 Media Guide

Africa Cup of Nations 2013 Media Guide 1 Index The Mascot and the Ball ................................................................................................................ 3 Stadiums ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Is South Africa Ready? ................................................................................................................... 6 History ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Top Scorers .................................................................................................................................. 12 General Statistics ......................................................................................................................... 14 Groups ......................................................................................................................................... 16 South Africa ................................................................................................................................. 17 Angola ......................................................................................................................................... 22 Morocco ...................................................................................................................................... 28 Cape Verde ................................................................................................................................. -

Indicates Significant Changes from Previous Year EMBARGOED

Sunday Times Generation Next Results 2015 Indicates significant changes from previous year As validated & supplied to Sunday Times on 30 March 2015 EMBARGOED & CONFIDENTIAL UNTIL 8 MAY 2015 Q1 Coolest Banks 2015 All groups 2015 Q1 Coolest Banks 2014 All Groups 2014 1 FNB 25.29 FNB 26.37 2 Standard Bank 23.72 Standard Bank 23.51 3 ABSA 18.99 ABSA 18.72 4 Capitec Bank 13.33 Nedbank 12.80 5 Nedbank 12.46 Capitec Bank 12.19 6 African Bank 1.97 Old Mutual Bank 2.31 7 Investec Bank 1.81 African Bank 1.74 8 Old Mutual Bank 1.65 Investec Bank 1.38 9 Postbank 0.68 Post Bank 0.90 10 Other 0.10 Other 0.08 Q2 Coolest Cellphones 2015 All Groups 2015 Q2 Coolest Cellphones 2014 All Groups 2014 1 Samsung 29.47 Apple iPhone 26.19 2 Apple iPhone 24.96 Samsung 23.78 3 BlackBerry 14.96 Blackberry 22.36 4 Nokia 11.90 Nokia 16.43 5 Huawei 7.01 Sony Ericsson 4.69 6 Sony Ericsson 6.80 Huawei 2.12 7 LG 2.59 HTC 1.89 8 Alcatel 1.52 LG 1.77 9 Motorola 0.46 Motorola 0.66 10 Other 0.32 Other 0.12 Q3 Coolest Clothing Stores 2015 All Groups 2015 Q3 Coolest Clothing Stores 2014 All Groups 2014 1 Mr Price 16.95 Mr Price 17.43 2 Edgars 9.44 Edgars 13.93 3 Markham 8.36 Woolworths 10.67 4 Woolworths 7.95 Sportscene 9.12 5 Sportscene 7.76 Identity 8.03 6 Cotton On 6.79 Truworths 7.35 7 Identity 6.69 Jay Jays 7.22 8 Truworths 6.66 Cotton On 6.12 9 Totalsports 6.55 Legit 4.33 10 Legit 4.39 Factorie 4.22 Q4 Coolest Domestic Airlines 2015 All Groups 2015 Q4 Coolest Domestic Airlines 2014 All Groups 2014 1 SAA (South African Airways) 39.07 SAA (South African Airways) 37.77 2 Mango -

Ziwaphi on the Road for 2015!

ONON THETHE ROADROAD www.nbcrfli.org.za 1st EDITION 2015 Welcome to the first edition of Ziwaphi on the Road for 2015! Ziwaphi on the Road is a newspaper designed for employee members of the NBCRFLI. Through this newspaper, we at the NBCRFLI continue to provide you with valuable information about our services, entertainment news, competitions and more. In this edition of Ziwaphi, we provide you with detailed information about our new Health Plan service provider, Affinity Health, who took over from Universal in January 2015. We also give you information about all the latest Council News including the appointment of our New National Secretary, Musa Ndlovu, who joined in September 2014. Batho also deals with your queries in “Ask Batho”. In the “Know your team” section, we look at the 2013/2014 PSL champions Mamelodi Sundowns. And who can forget the 26th of October 2014, when we all learned of Senzo Meyiwa’s tragic passing? The Orlando Pirates and South Africa captain made a huge contribution to football in Africa. We pay tribute to him in the Celebrity Spotlight section. Enjoy the edition and, as always, we welcome your comments. You may reach us on 011 703 7000 or visit our website www.nbcrfli.org.za to access our service query contact numbers. NBCRFLI Communications & Marketing Team CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR WINNERS! KEEP IN TOUCH & WIN THE ER24 EMERGENCY NUMBER: 084 124 KNOW YOUR TEAM Michael Thobela Jabulani Mtuli Reuben Mpembe Mokele Ephraim Phalatsane Mandla Nkosi Thula Trevor Sithole Nelson Kekana Mohau Mofokeng Anele Dungelo Mzingisi Foca Zamile Zacharia Saleni Godfrey Mafisa Jabulile Khanye Aaron Phogole Kaizer Ngobe COMPETITION RULES & WINNER SELECTION 1. -

Michigan Journal of International Affairs December 2014

Michigan Journal of International Affairs December 2014 LETTER FROM THE EDITORIAL BOARD International affairs are often described as a game. As time progresses, we carry an expectation that new participants will reveal unforeseen moves to alter its dynamics. Yet, events from this past year have cast doubt on this notion. Rather than integrating past decisions to form contemporary strategies, we have instead seen a recapitulation of earlier choices. New players have arrived at the table. But they are playing the same cards. Some of these hands have proven to be less than ideal. Despite the World Bank’s seemingly benign support of a hydroelectric dam project in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Dylan Warner explains how this parallels Belgian colonial exploits of the past. Furthermore, Trevor Grayeb’s article, “Playing War,” notes that in its steps toward remilitarization, Japan has only projected an illusion of strength, as it has repeatedly done in the past, as opposed to developing a concrete foreign policy. Lastly, Evan Charney posits that the Egyptian government’s attempts to suppress the Muslim Brotherhood will fail due to the organization’s experience in having endured similar crackdowns from prior regimes. At the same time, these former ploys can occasionally be effective. In “Just Watch Me,” Cody Giddings references the similarities between Canada’s current challenges and its problems with homegrown terrorism in the 1970s and indicates that Canada should look to the policies employed decades ago to confront the problems it faces today. The “(Un)Changed Game” then does not necessarily imply a cyclical nature of former events repeating in the future. -

Annual Report 2015-2016

Launched in 2001, Proudly South African Proudly SA continues to have a strong fo- (Proudly SA) is this country’s “Buy Local” cus on educating consumers, businesses Campaign which seeks to promote South and all state organs about the impact of African business, organisations, products their purchase behaviour and to drive con- and services that demonstrate high quali- sumer purchases to support local products ty, local content, fair labour practices and and services from key sectors identified by sound environmental standards. “Buy Lo- government. Proudly SA promotes mem- cal” activism is at the heart of the Cam- bers’ products and services to consumers, paign. businesses and all state organs while en- couraging South Africans to buy locally Proudly SA seeks to strongly influence made products bearing the Proudly SA procurement in the public and private logo. sectors, to increase local production and stimulate job creation. This is in line with Only businesses which adhere to the Cam- the government’s plans to revive South paigns’ uplifting and empowering criteria Africa’s economy, so that millions of jobs are granted membership and are allowed to can be created and unemployement can be use the Proudly SA logo which is a mark decreased to 15% as per the National De- of quality. velopment Plan. Part of Proudly SA’s mandate also includes promoting national pride, patriotism and social cohesion. PROUDLY SOUTH AFRICAN 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2015/16 Our Vision Proudly SA encourages the nation to make personal and organisational contributions to- wards economic growth and prosperity in South Africa, thereby increasing employment opportunities, economic growth and local value add while reinforcing national pride and patriotism. -

UAE Lists Brotherhood As a 'Terrorist Group'

SUBSCRIPTION SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 16, 2014 MUHARRAM 23, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Road accidents Obama gets Triumphant Gritty Djokovic killed 225 glimpse of probe sends subdues people in life as lame last-gasp data Nishikori to six months4 duck14 abroad from28 ‘alien world’ reach17 final UAE lists Brotherhood Min 11º Max 29º as a ‘terrorist group’ High Tide 05:16 & 19:44 Over 80 other Islamist outfits blacklisted Low Tide 00:12 & 12:33 40 PAGES NO: 16344 150 FILS DUBAI: The United Arab Emirates has for- Yesterday’s move echoes a similar move the UAE for its alleged link to Egypt’s abide by an agreement not to interfere in conspiracy theories mally designated the Muslim Brotherhood by Saudi Arabia in March and could Muslim Brotherhood, as a terrorist group. one another’s internal affairs. So far efforts and local affiliates as terrorist groups, state increase pressure on Qatar whose backing UAE authorities have cracked down on by members of the GCC, an alliance that news agency WAM reported yesterday, cit- for the group has sparked a row with fel- members of Al-Islah and jailed scores of also includes Oman and Kuwait, to resolve Let’s do some math ing a cabinet decree. The Gulf Arab state low Gulf monarchies. It also underscores Islamists convicted of forming an illegal the dispute have failed. The three states has also designated Nusra Front and the concern in the US-allied oil producer branch of the Brotherhood. Al-Islah denies mainly fell out with Qatar over the role of Islamic State, whose fighters are battling about political Islam and the influence of any such link, but says it shares some of Islamists, including the Muslim Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad, as terror- the Brotherhood, whose Sunni Islamist the Brotherhood’s Islamist ideology. -

Ronaldo Doubt for Messi Showdown

TTENNIS|ENNIS Page 4 RUGBY | Page 7 Djokovic wins Jones eager to Vienna opener see if Umaga to close in on makes the Sampras mark grade vs Italy Wednesday, October 28, 2020 FOOTBALL Rabia l 11, 1442 AH Covid-19-hit GULF TIMES Ronaldo in doubt for Messi clash SPORT Page 2 SPOTLIGHT FOCUS FIFA chief Infantino World 100m champ positive for Coleman banned, Covid-19 could miss Olympics Coleman previously escaped suspension on a technicality ahead of last year’s World Championships AFP suspended. Paris “I think the attempt on December 9th was a purposeful attempt to get me to miss a test,” Coleman said after he orld champion sprinter was charged in June. Christian Coleman is set “Don’t tell me I ‘missed’ a test if you to miss next year’s To- sneak up on my door (parked outside AFP kyo Olympics after being the gate and walked through...there’s Lausanne Wbanned from athletics for two years for no record of anyone coming to my anti-doping violations, the Athletics place) without my knowledge.” Integrity Unit (AIU) announced yes- Coleman said testers had visited IFA president Gianni Infan- terday. when he was out shopping for Christ- tino has contracted corona- The American, who won the men’s mas presents nearby, verifi able by bank virus, the world’s governing 100 metres at last year’s World Cham- statements and receipts. Fbody announced yesterday. pionships in Doha, was provisionally “I was more than ready and available The 50-year-old has mild symp- suspended for three ‘whereabouts fail- for testing and if I had received a phone toms and will remain in isolation for ures’ in June. -

Richard Poplak – Daily Maverick Saudi Crown Prince’S Business Empire’

19 21 26 29 30 Mail Guardian & 35 Years Mail Guardian35 Years For 35 years& the M&G has been at the forefront of journalism in South Africa. Mail Guardian35 Years Our newsroom& has been the training ground for the finest journalists in the country. It has also given birth to investigative units, such as amaBhungane and Bhekisisa. This has been possible because people like you support our newsroom. For just R75,00 per month, you can access all of this journalism and help grow the next generation of editors, reporters and columnists. Signup up here for this special offer that is exclusive to our colleagues. www.mg.co.za/journalistoffer Africa’s Best Read AFRICA’S BEST READ SOUTH AFRICA June 11 to 17 2010 Vol 26, No 22 May 23 to 29 2008⁄ Vol 24, No 21 / R16,50 in SA / www.mg.co.za / SMS “subs” to subscribe or “mg” for news via cellphone (one-off R1 charge) to 32368 Mozambique SOUTH AFRICA / Zambia ZMK11 850 / Zimbabwe $210 000 000 / Kenya Ksh277 / Angola US$6,10 / Botswana P15,28 / Swaziland E15,28 / Malawi MWK 283 / Lesotho M16,50 Celebrating 25 years of the M&G http://2010.mg.co.za www.mg.co.za Bumper special pull-out Chantel Dartnall Dada Masilo Daniel Buckland Lindi Matshikiza Lira Adam Levy Catherine Luckhoff Zibusiso Mkhwanazi Andy Higgins Claire Reid Nick Ferreira Pria Chetty Mpumelelo Paul Grootboom Musa Nxumalo Kesivan Ways of escape Naidoo BLK JKS Nicholas Hlobo Nontsikelelo Veleko Trevor Noah Warwick Allan Oliver Hermanus Barbara Mallinson Eusebius McKaiser Tania Steenkamp Castro Ngobese Xolani Mtshizana Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh