The Wolstenholmes.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

How to Register

HOW TO REGISTER DISABLED ACCESS KEARSLEY The practice premises provides marked disabled MEDICAL CENTRE parking, wheelchair access, a disabled toilet, and The practice runs an open list to patients all patient facilities are available on the ground Jackson Street, Kearsley level. residing within the practice boundary. Bolton BL4 8EP Our boundary covers postcodes:- Telephone : 01204 462200 VIOLENT/ABUSIVE PATIENTS Fax: 01204 462744 The practice has a zero tolerance policy. Any BL4 (Kearsley, Farnworth) www.kearsleymedicalcentre.nhs.uk patient demonstrating threatening abusive/violent M26 (Stoneclough, Prestolee, Ringley, behaviour will be removed from the practice list. DOCTORS Outwood) COMPLAINTS/SUGGESTIONS The practice runs an in-house complaints M27 (Clifton up to M62 junction 16 slip road). procedure which is available if you are unhappy Dr George Herbert Ogden with any aspect of our service. Please contact MBChB MRCGP DRCOG DFFP surgery for details. I To register with the practice you will need Dr Liaqat Ali Natha If you have a suggestion, to improve our service the following: MBChB please ask the receptionist for a form. 1 New Patient Registration Pack, Dr Sumit Guhathakurta OUT OF HOURS EMERGENCIES completed together with 2 forms of ID MBChB MRCGP If you require urgent medical advice please ring 2 Appointment with practice nurse. 111 for assistance. If you require urgent medical Dr Charlotte Moran assistance when the surgery is closed, please Patients may specify the GP they wish to be telephone the surgery for further information. MBChB nMRCGP 999 should be dialled for medical emergencies registered with at registration, although the only Dr Rebecca Cruickshank choice of GP cannot be absolute, it depends on MBChB MRCGP availability, appropriateness and reasonable- USEFUL TELEPHONE NUMBERS Dr Molly Douglas ness. -

Wayfarer Rail Diagram 2020 (TPL Spring 2020)

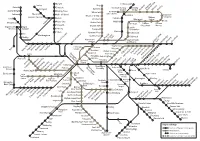

Darwen Littleborough Chorley Bury Parbold Entwistle Rochdale Railway Smithy Adlington Radcliffe Kingsway Station Bridge Newbold Milnrow Newhey Appley Bridge Bromley Cross Business Park Whitefield Rochdale Blackrod Town Centre Gathurst Hall i' th' Wood Rochdale Shaw and Besses o' th' Barn Crompton Horwich Parkway Bolton Castleton Oldham Orrell Prestwich Westwood Central Moses Gate Mills Hill Derker Pemberton Heaton Park Lostock Freehold Oldham Oldham Farnworth Bowker Vale King Street Mumps Wigan North Wigan South Western Wallgate Kearsley Crumpsall Chadderton Moston Clifton Abraham Moss Hollinwood Ince Westhoughton Queens Road Hindley Failsworth MonsallCentral Manchester Park Newton Heath Salford Crescent Salford Central Victoria and Moston Ashton-underStalybridgeMossley Greenfield -Lyne Clayton Hall Exchange Victoria Square Velopark Bryn Swinton Daisy HillHag FoldAthertonWalkdenMoorside Shudehill Etihad Campus Deansgate- Market St Holt Town Edge Lane Droylsden Eccles Castlefield AudenshawAshtonAshton Moss West Piccadilly New Islington Cemetery Road Patricroft Gardens Ashton-under-Lyne Piccadilly St Peter’s Guide Weaste Square ArdwickAshburys GortonFairfield Bridge FloweryNewton FieldGodley for HydeHattersleyBroadbottomDinting Hadfield Eccles Langworthy Cornbrook Deansgate Manchester Manchester Newton-le- Ladywell Broadway Pomona Oxford Road Belle Vue Willows HarbourAnchorage City Salford QuaysExchange Quay Piccadilly Hyde North MediaCityUK Ryder Denton Glossop Brow Earlestown Trafford Hyde Central intu Wharfside Bar Reddish Trafford North -

Classified Road List

CLASSIFIED HIGHWAYS Ainsworth Lane Bolton B6208 Albert Road Farnworth A575 Arthur Lane Turton B6196 Arthur Street Bolton B6207 Bank Street Bolton A676 Beaumont Road Bolton A58 Belmont Road Bolton A675 Blackburn Road Turton and Bolton A666 Blackhorse Street Blackrod B5408 Blackrod by-Pass Blackrod A6 Blair Lane Bolton Class 3 Bolton Road Farnworth A575 Bolton Road Kearsley A666 Bolton Road Turton A676 Bolton Road Farnworth A575 Bolton Road Kearsley A666 Bolton Road Westhoughton B5235 Bow Street Bolton B6205 Bradford Road Farnworth Class 3 Bradford Street Bolton A579 Bradshaw Brow Turton A676 Bradshaw Road Turton A676 Bradshawgate Bolton A575 Bridge Street Bolton B6205 Bridgeman Place Bolton A579 Buckley Lane Farnworth A5082 Bury New Road Bolton A673 Bury Road Bolton A58 Cannon Street Bolton B6201 Castle Street Bolton B6209 Chapeltown Road Turton B6319 Chorley New Road Horwich and Bolton A673 Chorley Old Road Horwich and Bolton B6226 Chorley Road Blackrod A6 Chorley Road Westhougton A6 Chorley Road Blackrod B5408 Church Lane Westhoughton Church Street Little Lever A6053 Church Street Westhoughton B5236 Church Street Blackrod B5408 Church Street Horwich B6226 College Way Bolton B6202 Colliers Row Road Bolton Class 3 Cricketer’s Way Westhoughton A58 Crompton Way Bolton A58 Crown Lane Horwich B5238 Dark Lane Blackrod Class 3 Darwen Road Turton B6472 Deane Road Bolton A676 Deansgate Bolton A676 Derby Street Bolton A579 Dicconson Lane Westhoughton B5239 Dove Bank Road Little Lever B6209 Eagley Way Bolton Class 3 Egerton Street Farnworth A575 -

Communicating with the Neighbourhoods

Communicating with the Neighbourhoods June 2018 This work was commissioned from Healthwatch Bolton by Bolton CCG as part of the Bolton Engagement Alliance Communicating with the Neighbourhoods - June 2018 1 Communicating with the Neighbourhoods - Abstract This report is based on conversations or responses freely given by members of the public. Where possible quotations are used to illustrate individual or collectively important experiences. Engagement officers collect responses verbatim and we also present these in our final report as an appendix. This is important in showing the accuracy of our analysis, and so that further work can be done by anyone wishing to do so. A full explanation of the guiding principles and framework for how we do engagement and analysis can be found online on our website www.healthwatchbolton.co.uk. HWB - Communicating with the Neighbourhoods - June 2018 2 Communicating with the Neighbourhoods - Disclaimer Please note that this report relates to findings observed and contributed by members of the public in relation to the specific project as set out in the methodology section of the report. Our report is not a representative portrayal of the experiences of all service users and staff, only an analysis of what was contributed by members of the public, service users, patients and staff within the project context as described. HWB - Communicating with the Neighbourhoods - June 2018 3 Communicating with the Neighbourhoods - Background This piece of work builds on Neighbourhood Engagement Workshops carried out in September and October 2017 by the Bolton Engagement Alliance. The reports of these workshops make a number of suggestions as to how individuals in the Neighbourhoods could be kept informed about developments in health and social care. -

Bolton Neighbourhood Engagement Report 2017

Bolton Neighbourhood Engagement Report 2017 Bolton Locality Plan and Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Devolution Contents Executive Summary .............................................3 Introduction .................................................12 Methodology ...........................................13 Individual Neighbourhood reports ............16 Central and Great Lever ..................16 Farnworth and Kearsley ...................24 Horwich and Blackrod .....................34 Chorley Roads ..............................47 Westhoughton ..............................55 Breightmet and Little Lever ..............62 Turton .......................................69 Crompton and Halliwell ..................75 Rumworth ..................................82 Executive Summary This report provides the main findings of Neighbourhood workshops aimed at bringing Bolton residents together to explore Bolton’s Locality plan and share ideas, experiences and opinions under the following key themes: What assets do communities have to manage their own health and wellbeing? What makes it difficult for residents to manage their own health and wellbeing? How do residents view the new roles in primary care? How can residents participate in service development? What are the next steps towards achieving outcomes that works for all? residents Key Statistics 262 Total number of people who took part in the workshops Participants in each Neighbourhood Although Blackrod and Horwich belong to the same GP cluster two separate workshops were conducted in this area 18% 17% 16% 47 44 41 11% 10 9% 7 30 7% % 4% 23 % 26 1% 19 19 10 3 Blackrod Breighmet/Little Lever Central/Great Lever Chorley Roads Crompton/Halliwell Rumsworth Farnworth/Kearsley Horwich Turton Westhoughton 92% said the workshops “I will use this information to explain to other met their expectations people I work with in my voluntary capacity and also people I live with in the area. Local people will not be aware of the term devolution itself and it needs to be explained in non-jargon terms. -

Strategic Flood Risk Assessment for Greater Manchester

Strategic Flood Risk Assessment for Greater Manchester Sub-Regional Assessment Appendix B – Supporting Information “Living Document” June 2008 Association of Greater Manchester Authorities SFRA – Sub-Regional Assessment Revision Schedule Strategic Flood Risk Assessment for Greater Manchester June 2008 Rev Date Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 01 August 2007 DRAFT Michael Timmins Jon Robinson David Dales Principal Flood Risk Associate Director Specialist Peter Morgan Alan Houghton Planner Head of Planning North West 02 December DRAFT FINAL Michael Timmins Jon Robinson David Dales 2007 Principal Flood Risk Associate Director Specialist Peter Morgan Alan Houghton Planner Head of Planning North West 03 June 2008 FINAL Michael Timmins Jon Robinson David Dales Principal Flood Risk Associate Director Specialist Anita Longworth Alan Houghton Principal Planner Head of Planning North West Scott Wilson St James's Buildings, Oxford Street, Manchester, This document has been prepared in accordance with the scope of Scott Wilson's M1 6EF, appointment with its client and is subject to the terms of that appointment. It is addressed to and for the sole and confidential use and reliance of Scott Wilson's client. Scott Wilson United Kingdom accepts no liability for any use of this document other than by its client and only for the purposes for which it was prepared and provided. No person other than the client may copy (in whole or in part) use or rely on the contents of this document, without the prior written permission of the Company Secretary of Scott Wilson Ltd. Any advice, opinions, Tel: +44 (0)161 236 8655 or recommendations within this document should be read and relied upon only in the context of the document as a whole. -

2018-0411 Response by Greater Manchester Police

GREATER MANCHESTER POLICE Ian Hopkins QPM, MBA Chief Constable Ms Joanne Kearsley HM Senior Coroner HM Coroner's Court The Phoenix Centre, L/Cpl Stephen Shaw MC Way Heywood OL191LR 28 February 2019 Dear Ms Kearsley Re: Regulation 28 Report following the Inquest touching upon the death of Gregory Rewkowski Thank you for your report sent by email dated 3 January 2019 in respect of Gregory Rewkowski (deceased) and pursuant to Regulations 28 and 29 of The Coroners (Investigations) Regulations 2013 and paragraph 7, Schedule 5 of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009. Having carefully considered your report and the matters therein, I reply to the concerns raised as follows: Extract from Regulation 28, point 1: There is a lack of acknowledgement of the role of the police when dealing with people who are taken on a Section 136 from their own home. The Court did not explore the numbers of Section 136 patients who are taken to a place of safety from their home address. The Court heard how Mr Rewkowski had been taken from his own home on the 1th September. Other agencies are clearly familiar with this process and how GMP facilitate this. However this was also used as an explanation as to why GMP may have been restricted in what they could do on the 2th and 2Efh October i.e. " ... there is nothing we can do if we attend at his own home. We have no powers." There appears to be a significant difference between the legal position and the practical reality of how police deal with such matters if they are called to a home address. -

Greater Manchester Green Belt: Additional Assessment of Sites Outside of the Green Belt

Greater Manchester Green Belt: Additional Assessment of Sites Outside of the Green Belt Study Background In 2016, LUC was commissioned on behalf of the ten Greater Manchester Authorities by Manchester City Council to undertake an assessment of the Green Belt within Greater Manchester. The study provided an objective, evidence-based and independent assessment of how Manchester’s Green Belt contributes to the five purposes of Green Belt, as set out in paragraph 80 of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) (see Box 1 below). The original assessment also examined the performance of 58 potential additional areas of land that currently lie outside the Green Belt. Box 1: The purposes of Green Belt 1. To check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas. 2. To prevent neighbouring towns merging into one another. 3. To assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment. 4. To preserve the setting and special character of historic towns. 5. To assist in urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land. In 2018, LUC were commissioned to undertake an assessment of 32 additional areas of land that do not lie within the Manchester Green Belt, to assess how they perform against the NPPF Green Belt purposes. The additional areas were identified by the authorities of Bolton, Bury, Oldham, Rochdale, Salford, Stockport and Wigan. The assessment was undertaken using the same assessment methodology used for the 2016 study which is detailed in Chapter 3 of the Greater Manchester Green Belt Assessment (July 2016). This methodology is not repeated here but as per the original study it involved both a desked based assessment and field visits to all of the areas of land. -

World Cup Pack

The BBC team Who’s who on the BBC team Television Presentation Team – BBC Sport: Biographies Gary Lineker: Presenter is the only person to have won all of the honours available at club level at least twice and captained the Liverpool side to a historic double in 1986. He also played for Scotland in the 1982 World Cup. A keen tactical understanding of the game has made him a firm favourite with England’s second leading all-time goal-scorer Match Of The Day viewers. behind Sir Bobby Charlton, Gary was one of the most accomplished and popular players of his Mark Lawrenson: Analyst generation. He began his broadcasting career with BBC Radio 5 in Gary Lineker’s Football Night in 1992, and took over as the host of Sunday Sport on the re-launched Radio Five Live in 1995. His earliest stint as a TV pundit with the BBC was during the 1986 World Cup finals following England’s elimination by Argentina. Gary also joined BBC Sport’s TV team in 1995, appearing on Sportsnight, Football Focus and Match Of The Day, and became the regular presenter of Football Focus for the new season. Now Match Of The Day’s anchor, Gary presented highlights programmes during Euro 96, and hosted both live and highlights coverage of the 1998 World Cup finals in France. He is also a team captain on BBC One’s hugely successful sports quiz They Think It’s All Over. Former Liverpool and Republic of Ireland defender Mark Lawrenson joined BBC Alan Hansen: Analyst Television’s football team as a pundit on Match Until a knee injury ended his playing career in Of The Day in June 1997. -

Greater Manchester

Greater Manchester Local Pilot The comprehensive plan to reduce inactivity and increase participation in physical activity and sport aligned to GM Population Health priority themes and wider reform agenda. Through system wide collaboration we aim to get 75% of people active or fairly active by 2025. The GM Moving Whole System Approach Although, in reality it’s not that neat. More like this. Greater Manchester Devolution: Transport (including buses and potentially rail stations), Strategic Planning, Housing Investment Fund, Police and Crime, Work and Health, FE and Apprenticeship Grants), Integrated GM Health and Social Care Partnership. Welcome • Children and young people aged 5-18 in out-of- school settings. • People out of work,Welcome and people in work but at risk of becoming workless. • People aged 40-60 with, or at risk of, long term conditions: specifically cancer, cardiovascular disease and respiratory disorders. Bolton Bury Manchester Marketing and Communications Marketing Oldham Engagement Workforce Evaluation Rochdale Salford Stockport Tameside Trafford Wigan Milkstone & Deeplish Breightmet & Little Lever West Middleton Bury East Central & Great Lever Farnworth & Kearsley Radcliffe Glodwick Wigan Central Failsworth Hindley Welcome Leigh Hyde East Manchester Glossop Brinnington Partington Workforce 1. ‘Every Contact Counts’: embed physical activity advocacy and brief interventions through clinical and community champions in a distributed leadership approach across the Greater Manchester systemWelcome and at every layer in the system. 2. Delivery of “Leading GM Moving” workforce transformation programme. • Rochdale, Trafford, Manchester, Bolton, Salford, Bury, Oldham • PHE Clinical ChampionsWelcome • Active Practices • Digital Elements • Primary Care Networks • Link Workers/Care navigators – Social Prescribing • Patient advisory groups • CCG / DPH / LCO • GM Approach • GM DPH group • Health and WellbeingWelcome Board. -

S Ilv E R L Inin Gs

David Hartrick David David Hartrick SILVER LININGS SILVER SILVER LININGS Bobby Robson’s England Contents Foreword 9 Prologue 13 1. Before 19 2 1982 67 3. 1983 95 4. 1984 115 5. 1985 136 6 1986 158 7. 1987 185 8. 1988 205 9. 1989 233 10. 1990 255 11. After 287 Acknowledgements 294 Bibliography and References 296 Before ENGLISH FOOTBALL had spent a lifetime preparing to win the World Cup in 1966 To some it was less a sporting endeavour and more a divine right As Bobby Moore raised the Jules Rimet Trophy high, the home nation’s island mentality had only been further enhanced Here was tacit confirmation of what many in charge had assumed either publicly or privately; England were the best team in the world, and quite possibly always had been Football had come home It would be fair to say that a good part of that mentality came from the Football Association’s long-standing attitude towards the international game; chiefly one of gradual adoption due to a deep-rooted superiority complex plus viewing change by where it came from rather than the actual effect it had England created modern football, and thus would always be the ones who mastered it, many reasoned In truth neither side of that statement was particularly sound, but it would be fair to say the game’s codification at least owed the country a grand debt England may have played football’s first official international fixture, against Scotland in 1872, but it then watched on impassively as other nations expanded their horizons Preferring to play home internationals, on the whole there