The Maryland Crab Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecological Condition of US Mid-Atlantic Estuaries, 1997–1998

Marine Pollution Bulletin 46 (2003) 1224–1244 www.elsevier.com/locate/marpolbul Review Ecological condition of US Mid-Atlantic estuaries, 1997–1998 John A.Kiddon a,*, John F.Paul b, Harry W.Buffum c, Charles S.Strobel a, Stephen S.Hale a, Donald Cobb a, Barbara S.Brown a a US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, Atlantic Ecology Division, 27 Tarzwell Drive, Narragansett, RI 02882, USA b US Environmental Protection Agency, ORD, NHEERL, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709, USA c Computer Sciences Corporation, 27 Tarzwell Drive, Narragansett, RI 02882, USA Abstract The Mid-Atlantic Integrated Assessment (MAIA-Estuaries) evaluated ecological conditions in US Mid-Atlantic estuaries during the summers of 1997 and 1998.Over 800 probability-based stations were monitored in four main estuarine systems––Chesapeake Bay, the Delaware Estuary, Maryland and Virginian coastal bays, and the Albemarle–Pamlico Estuarine System.Twelve smaller estuaries within the four main systems were also assessed to establish variance at the local scale.A subset of the MAIA-Estuaries data is used here to estimate the extent of eutrophication, sediment contamination, and benthic degradation in mid-Atlantic estuaries.An Envi- ronmental Report Card and Index of Environmental Integrity summarize conditions in individual estuaries, the four estuarine systems, and the entire MAIA region.Roughly 20–50% of the region showed signs of eutrophication (high nutrients, excessive production of organic matter, poor water clarity, or depleted dissolved oxygen), 30% had contaminated sediments, and 37% had degraded benthic communities.Compared with the Environmental Monitoring and Assessment Program (EMAP)-Virginian Province study in 1990– 1993, larger fractions of Chesapeake Bay (17%) and Delaware River (32%) had increased metals or organics in sediments. -

Nautical Information for Skippers and Crews

Sail Plan Pentagon Sailing Club 2016 Memorial Day Raftup: “STORM FRONT COMING” 2830 May 2016 Nautical Information for Skippers and Crews FLOAT PLAN ******************************************************************************************** References: NOAA Charts 12270 Chesapeake Bay – Chesapeake Eastern Bay and South River; 1:40,000 12266 Chesapeake Bay – Chesapeake – Choptank and Herring Bay; 1:40,000 12280 Chesapeake Bay – 1:200,000 Pentagon Sailing Club RaftUp Guidelines (revised 06/2005; link online at the PSC site under “RaftUp”) Saturday, 28 May 16. Sail from Annapolis, MD the Chesapeake Bay to Trippe Creek, vicinity of Choptank River. Raft up Saturday night (see Navigation below). Distance from Annapolis (direct route past Thomas Point to Choptank River, Tred Avon River, then Trippe Creek and raft up location) is approximately 33 nm Sunday, 29 May 16. Exit Trippe Creek, Tred Avon River, then Choptank River to Campbell’s Boatyard LLC, Bachelor’s Point Marina (Oxford, MD). Dinner will be held at “The Masthead at Pier Street Marina” restaurant in Oxford, MD; cocktails from 5pm, and dinner from 6 to 8pm. Monday, 30 May 16. Sail back to respective points of origin NAVIGATION ******************************************************************************************** Saturday, 28 May: Sail from Annapolis, MD to Raft up destination is in the Trippe Creek vic 038º 42.8 North; 076º 07.3 West. See Chart A and B. From Annapolis R “2” Fl R 2.5s (Lat 038º 56.4 N; Lon 076º 25.3 W) Sail from R “2” Fl R 2.5s 185º M to WP A (Lat 038º -

Accomack County, Virginia Shoreline Inventory Report Methods and Guidelines

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 9-2016 Accomack County, Virginia Shoreline Inventory Report Methods and Guidelines Marcia Berman Virginia Institute of Marine Science Karinna Nunez Virginia Institute of Marine Science Sharon Killeen Virginia Institute of Marine Science Tamia Rudnicky Virginia Institute of Marine Science Julie Bradshaw Virginia Institute of Marine Science See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Berman, M., Nunez, K., Killeen, S., Rudnicky, T., Bradshaw, J., Angstadt, K., Tombleson, C., Duhring, K., Brown, K., Hendricks, J., Weiss, D., Hershner, C., & Comprehensive Coastal Inventory Program. (2016) Accomack County, Virginia Shoreline Inventory Report Methods and Guidelines. Special Report in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering (SRAMSOE) No. 450. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. http://doi.org/10.21220/V58C79 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Marcia Berman, Karinna Nunez, Sharon Killeen, Tamia Rudnicky, Julie Bradshaw, Kory Angstadt, Christine Tombleson, Karen Duhring, Kallie Brown, Jessica Hendricks, David Weiss, Carl Hershner, and Comprehensive Coastal Inventory Program This report is available at W&M ScholarWorks: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports/61 Accomack County, Virginia Shoreline Inventory Report Methods and Guidelines Prepared By: Comprehensive Coastal Inventory Program Center for Coastal Resources Management Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia September 2016 Special report in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering No. -

2012-AG-Environmental-Audit.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER ONE: YOUGHIOGHENY RIVER AND DEEP CREEK LAKE .................. 4 I. Background .......................................................................................................... 4 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ........................................................... 9 III. The Youghiogheny River/Deep Creek Lake Audit, May 16, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned............................................................................................. 12 CHAPTER TWO: COASTAL BAYS ............................................................................. 15 I. Background ........................................................................................................ 15 II. Active Enforcement Efforts and Pending Matters ............................................. 17 III. The Coastal Bays Audit, July 12, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned .. 20 CHAPTER THREE: WYE RIVER ................................................................................. 24 I. Background ........................................................................................................ 24 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ......................................................... 26 III. The Wye River Audit, October 10, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned 27 CHAPTER FOUR: POTOMAC RIVER NORTH BRANCH AND SAVAGE RIVER 31 I. Background ....................................................................................................... -

Shoreline Management in Chesapeake Bay C

Shoreline Management In Chesapeake Bay C. S. Hardaway, Jr. and R. J. Byrne Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William and Mary 1 Cover Photo: Drummond Field, Installed 1985, James River, James City County, Virginia. This publication is available for $10.00 from: Sea Grant Communications Virginia Institute of Marine Science P. O. Box 1346 Gloucester Point, VA 23062 Special Report in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 356 Virginia Sea Grant Publication VSG-99-11 October 1999 Funding and support for this report were provided by... Virginia Institute of Marine Science Virginia Sea Grant College Program Sea Grant Contract # NA56RG0141 Virginia Coastal Resource Management Program NA470Z0287 WILLIAM& MARY Shoreline Management In Chesapeake Bay By C. Scott Hardaway, Jr. and Robert J. Byrne Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 1999 4 Table of Contents Preface......................................................................................7 Shoreline Evolution ................................................................8 Shoreline Processes ..............................................................16 Wave Climate .......................................................................16 Shoreline Erosion .................................................................20 Reach Assessment ................................................................23 Shoreline Management Strategies ......................................24 Bulkheads and Seawalls -

Choptank Tributary Summary: a Summary of Trends in Tidal Water Quality and Associated Factors, 1985-2018

Choptank Tributary Summary: A summary of trends in tidal water quality and associated factors, 1985-2018. June 7, 2021 Prepared for the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) Partnership by the CBP Integrated Trends Analysis Team (ITAT) This tributary summary is a living document in draft form and has not gone through a formal peer review process. We are grateful for contributions to the development of these materials from the following individuals: Jeni Keisman, Rebecca Murphy, Olivia Devereux, Jimmy Webber, Qian Zhang, Meghan Petenbrink, Tom Butler, Zhaoying Wei, Jon Harcum, Renee Karrh, Mike Lane, and Elgin Perry. 1 Contents 1. Purpose and Scope .................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Location ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Watershed Physiography .................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Land Use .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Land Use ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.3 Tidal Waters and Stations ................................................................................................................... 8 3. Tidal -

MDE-Water Pollution

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................... 1 Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION .................................................................................................................... 1 Chapters 01-10 ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................... 2 Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION .................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 01 General ......................................................................................................................................... 2 .01 Definitions................................................................................................................................................. 3 .02 Principles of Water Pollution Control.................................................................................................... -

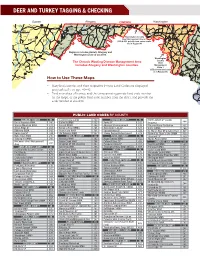

Deer and Turkey Tagging & Checking

DEER AND TURKEY TAGGING & CHECKING Garrett Allegany CWDMA Washington Frederick Carroll Baltimore Harford Lineboro Maryland Line Cardiff Finzel 47 Ellerlise Pen Mar Norrisville 24 Whiteford ysers 669 40 Ringgold Harney Freeland 165 Asher Youghiogheny 40 Ke 40 ALT Piney Groev ALT 68 615 81 11 Emmitsburg 86 ge Grantsville Barrellville 220 Creek Fairview 494 Cearfoss 136 136 Glade River aLke Rid 546 Mt. avSage Flintstone 40 Cascade Sabillasville 624 Prospect 68 ALT 36 itts 231 40 Hancock 57 418 Melrose 439 Harkins Corriganville v Harvey 144 194 Eklo Pylesville 623 E Aleias Bentley Selbysport 40 36 tone Maugansville 550 419410 Silver Run 45 68 Pratt 68 Mills 60 Leitersburg Deep Run Middletown Springs 23 42 68 64 270 496 Millers Shane 646 Zilhman 40 251 Fountain Head Lantz Drybranch 543 230 ALT Exline P 58 62 Prettyboy Friendsville 638 40 o 70 St. aulsP Union Mills Bachman Street t Clear 63 491 Manchester Dublin 40 o Church mithsburg Taneytown Mills Resevoir 1 Aviltn o Eckhart Mines Cumberland Rush m Spring W ilson S Motters 310 165 210 LaVale a Indian 15 97 Rayville 83 440 Frostburg Glarysville 233 c HagerstownChewsville 30 er Springs Cavetown n R 40 70 Huyett Parkton Shawsville Federal r Cre Ady Darlingto iv 219 New Little 250 iv Cedar 76 140 Dee ek R Ridgeley Twiggtown e 68 64 311 Hill Germany 40 Orleans r Pinesburg Keysville Mt. leasP ant Rocks 161 68 Lawn 77 Greenmont 25 Blackhorse 55 White Hall Elder Accident Midlothian Potomac 51 Pumkin Big pringS Thurmont 194 23 Center 56 11 27 Weisburg Jarrettsville 136 495 936 Vale Park Washington -

Lll'"Iii""!Lllliillllliil MARYLAND BIRDLIFE Il~Ll;I,I,,,,,Illlllllllil

ISSN 0147-9725 lll'"iii""!lllliillllliil MARYLAND BIRDLIFE il~ll;i,i,,,,,illlllllllil, oo o L "8 N ,.j SEPTEMBER 1988 VOLUME 44 NUMBER 3 MARYLAND ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY, INC. Cylburn Mansion, 4915 Greenspring Ave., Baltimore, Maryland 21209 STATE OFFICERS FOR JUNE 1988 TO JUNE 1989 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL President: Robt. F. Ringlet, 6272 Pinyon Pine Ct., Eldersburg, MD 21784 549-6031 V. President:Richard J. Dolesh, 17800 Croom Rd., Brandywine, MD 20613 627-6074 Treasurer: Emily Joyce, 816 Oak Trail, Crownsville, MD 21032 768-0142 Secretary: Patricia J. Moore, 24600 Woodfield Rd., Damascus, MD 21403 253-2796 Exec. Secy.: Joy Aso, 1250 4th St., SW, Washington, D.C. 20024 (202) 554-8529 Past Pres.: CDR Anthony White, 5872 Marbury Rd., Bethesda, MD 20817229-1641 STATE DIRECTORS Allegany: *Teresa Simons Howard: *Thomas Strikwerda Mark Weatherholt Jane H. Farrell Ralph Geuder Anne Arundel: *Sue Ricciardi Paul Zucker Helen Ford Dorothy Mumford Jug Bay: *Jean Tierney Joan Stephens Baltimore: *William Newman John Cullom Kent: *John Lorenz Graham Egerton Margaret Duncan A. MacDonough Plant Robert F. Ringler Montgomery: *Henry Bielstein Stephen W. Simon Margaret Donnald Karen Skuldt John Malcolm Joy Wheeler Lola Oberman Caroline: *Mariana Nuttle Patuxent: *Sam Droege Oliver Smith Chandler S. Robbins Carroll: *Melinda Byrd Talbot: *Lester Coble Wayne Gordon Jeff Effinger Steve Goodbred Frederick: *Stauffer Miller Melvin Bennett Washington: *Robert Keedy Joseph Swope, Jr. Harford: *Dennis Kirkwood Todd Holden Wicomico: *Gall Vaughn William Russell Charles Vaughn *Denotes Chapter President Active Membership (adults) 6.00 plus local chapter dues Student Membership (full-time students) 2.00 plus local chapter dues Junior Membership (under 18 years) 1.00 plus local chapter dues Family Membership (Mr. -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

State of Maryland Action Plan For

LARRY HOGAN Governor BOYD K. RUTHERFORD Lt. Governor KENNETH C. HOLT Secretary ELLINGTON CHURCHILL, JR. Deputy Secretary The attached document, the Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development’s “State of Maryland Action Plan for Disaster Recovery – Grant #2”, was completed and approved in May 2014, prior to the accession of the current state administration under Governor Larry Hogan and Lt. Governor Boyd K. Rutherford. This document remains in force, and has been unchanged and unedited from its original format. MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT 7800 HARKINS ROAD, LANHAM, MD 20706 301-429-7400, TOLL-FREE 800-756-0119, FAX 240-334-4732 State of Maryland Action Plan for Disaster Recovery – Grant #2 Community Development Block Grant Program Submitted to HUD on March 25, 2014 Approved by HUD May 23, 2014 Martin O’Malley, Governor Anthony G. Brown, Lieutenant Governor Raymond A. Skinner, Secretary Clarence J. Snuggs, Deputy Secretary Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development 100 Community Place Crownsville, MD 21032 Email: [email protected] Phone: 410/514-7256 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary II. Introduction III. Eligible Storm Events IV. Method of Distribution V. Application Review Process VI. Funding Recommendations VII. Proposed Use of Funding VIII. Needs Assessments a. Allegany County – Hurricane Sandy b. Dorchester County – Hurricane Sandy c. Garrett County – Hurricane Sandy d. Somerset County – Hurricane Sandy e. Charles County – Tropical Storm Lee IX. Risk Analysis for Infrastructure Projects X. Grant Administration XI. Regulations, Policies and Requirements for Funded Projects XII. Certifications This plan was prepared by the Maryland Deparment of Housing and Community Development. -

Summary of Decisions Regarding Nutrient and Sediment Load Allocations and New Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) Restoration Goals

To: Principal Staff Committee Members and Representatives of Chesapeake Bay “Headwater” States From: W. Tayloe Murphy, Jr., Chair Chesapeake Bay Program Principals’ Staff Committee Subject: Summary of Decisions Regarding Nutrient and Sediment Load Allocations and New Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) Restoration Goals For the past twenty years, the Chesapeake Bay partners have been committed to achieving and maintaining water quality conditions necessary to support living resources throughout the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem. In the past month, Chesapeake Bay Program partners (Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Chesapeake Bay Commission) have expanded our efforts by working with the headwater states of Delaware, West Virginia and New York to adopt new cap load allocations for nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment. Using the best scientific information available, Bay Program partners have agreed to allocations that are intended to meet the needs of the plants and animals that call the Chesapeake home. The allocations will serve as a basis for each state’s tributary strategies that, when completed by April 2004, will describe local implementation actions necessary to meet the Chesapeake 2000 nutrient and sediment loading goals by 2010. This memorandum summarizes the important, comprehensive agreements made by Bay watershed partners with regard to cap load allocations for nitrogen, phosphorus and sediments, as well as new baywide and local SAV restoration goals. Nutrient Allocations Excessive nutrients in the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal tributaries promote undesirable algal growth, and thereby, prohibit light from reaching underwater bay grasses (submerged aquatic vegetation or SAV) and depress the dissolved oxygen levels of the deeper waters of the Bay.