I CESAREAN SECTION DELIVERY in INDIA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

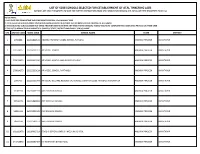

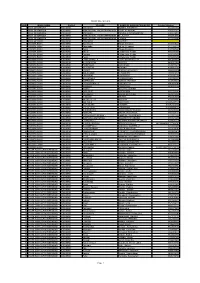

List of 6038 Schools Selected for Establishment of Atal Tinkering

LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. LAST DATE FOR COMPLETING THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS : 31st JANUARY 2020 2. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST OPEN A NEW BANK ACCOUNT IN A PUBLIC SECTOR BANK FOR THE PURPOSE OF ATL GRANT. 3. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST NOT SHARE THEIR INFORMATION WITH ANY THIRD PARTY/ VENDOR/ AGENT/ AND MUST COMPLETE THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS ON THEIR OWN. 4. THIS LIST IS ARRANGED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER OF STATE, DISTRICT AND FINALLY SCHOOL NAME. S.N. ATL UID CODE UDISE CODE SCHOOL NAME STATE DISTRICT 1 2760806 28222800515 ANDHRA PRADESH MODEL SCHOOL PUTLURU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 2 132314217 28224201013 AP MODEL SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 3 574614473 28223600320 AP MODEL SCHOOL AND JUNIOR COLLEGE ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 4 278814373 28223200124 AP MODEL SCHOOL RAPTHADU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 5 2995459 28222500704 AP SOCIAL WELFARE RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL JUNIOR COLLEGE FOR GIRLS KURUGUNTA ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 6 13701194 28220601919 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 7 15712075 28221890982 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 8 56051196 28222301035 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 9 385c1160 28221591153 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 10 102112978 28220902023 GOOD SHEPHERD ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 11 243715046 28220590484 K C NARAYANA E M SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. -

Form GST REG-06 Registration Certificate

(Amended) Government of India Form GST REG-06 [See Rule 10(1)] Registration Certificate Registration Number :36AAACB0446L1ZT 1. Legal Name BLUE DART EXPRESS LIMITED 2. Trade Name, if any blue dart express limited 3. Constitution of Business Private Limited Company 4. Address of Principal Place of 8-2-248/1/7/71 ,71A PLOT NO.71, SARADA CHAMBERS, Business NAGARJUNA HILLS, nagarjuna circle, Hyderabad, Telangana, 500082 5. Date of Liability 01/07/2017 6. Date of Validity From 01/07/2017 To Not Applicable 7. Type of Registration Regular 8. Particulars of Approving Authority Signature Name Designation Jurisdictional Office 9. Date of issue of Certificate 21/04/2020 Note: The registration certificate is required to be prominently displayed at all places of Business/Office(s) in the State. This is a system generated digitally signed Registration Certificate issued based on the deemed approval of application on 21/04/2020 . Annexure A Details of Additional Place of Business(s) GSTIN 36AAACB0446L1ZT Legal Name BLUE DART EXPRESS LIMITED Trade Name, if any blue dart express limited Total Number of Additional Places of Business(s) in the State 40 Sr. No. Address 1 RAJIV GANDHI INTL. AIRPORT, NEAR CARGO FACILITY,SHAMS, ADIBATLA, Ranga Reddy, Telangana, 501510 2 P AND G HOME PRODUCTS IN PLANT, SURVEY 208, J P DARGA RD.,, KOTHURE MANDAL, HYDERABAD AZH, Hyderabad, Telangana, 511111 3 3-6-278-279 G2, THOMAS PRABHU RELIANCE RESIDEN, HIMAYAT NAGAR HYDERABAD BAS, Hyderabad, Telangana, 500029 4 FLAT-G-8,9 AND 10,PRIME LOTUS, APTTS, SURVERY-226-A-1,, 226-A-2,235,227, BACHUPAL, HYDERABAD BCP, Hyderabad, Telangana, 500090 5 BANJARA HILLS SERV.CENTRE, 8-2-686-6, GROUND FLOOR, GOKUL KIMTEE BUILDING, RD. -

1. Agriculture

1. AGRICULTURE • Agriculture sector plays a pivotal role in meeting the dietary requirements of one of the most densely populated districts - Medchal – Malkajgiri. • Total Agriculture land in the District (as per RB record) : 70000 Ac Net cultivated area : 26807 Ac • Predominant crops: Paddy (47% of cultivated area), Maize (11%), Fodder (6%), Redgram (3%), Cotton (2%), Other food crops (30%) of cultivated area. • Soils : Red soil is predominant (70%), Black soils (30%) • Source of irrigation: Bore wells : 14000 Ac Minor irrigation tanks: 2600 Ac Musi : 3000 Ac • Rainfall Normal :711 mm Actual: 813.7mm % Deviation: 14 Normal No .of Rainy Days : 59 • Market facility : Through procurement centres, AMC Medchal, Pvt traders, Local markets • Agri Input supply : Subsidy seed is distributed to farmers through online portal (OSSDS) at 7 notified sale points (3PACS, 3FACS, 1 MGC), Major sales are through private dealers(22) • Fertilizer supply through PACS, FSCS, Pvt dealers (42). • Rythu Samanvaya Samithies: 101 GRSS, 6MRSS 1ZRSS: Total 108 Flagship programmes / Schemes implemented during the Yr. 2019-20 Sl. Achievem % Scheme Target Remarks No ent Ach I FLAG SHIP PROG. Bank details of 27451farmers (except give it up, not 33334 23951 Far 71% interested cases) updated and Rythu Bandhu 1 Farmers 25.35 sent to C&DA. However Kharif 2019 34.85 Crores Crores 73% Amount credited to 23951 accounts by C&DA to the extent of budget released. 21307 Far 18327 86 % Rabi 2019- 20 Under progress at C&DA level 23.53 Crore 13.69Cr 56% 2 Rythu Bima 39640 39640 a -

Abondnend / Unclaimed Vehicles List of Alwal Traffic Police Station, Cybereabad

ABONDNEND / UNCLAIMED VEHICLES LIST OF ALWAL TRAFFIC POLICE STATION, CYBEREABAD. Vehicle Sl. No Vehicle Model Make Engine No Chassis No Case Details Status of Case Owner ship Details Remarks RegistrationNumber RAMJI,SINGH S/o RAM BACCAN SINGH HERO HONDA PASSION DD CS.No. D NO 5-3-68/161, VENKATESHWARA 1 AP28DA9946 HA10EB8GJ80449 MBLHA10EL8GJ39431 Pending Plus-2008 444/14 (2014) COLONY,BUDWEL RR DIST,RAJENDRANAGAR MAHMOOD ALI S/o Mahaboob ali r/o 17-8- DD CS.No. 2 HONDA DIO - 2003 AP11M2161 JF11E0030988 ME4JF115J38025915 Pending 415/1/D,BAGH E JAHAN ARA, YAKUTHPURA 81/15 (2015) HYDERABAD MOHD SIDDIQ s/o MOHD. QASIM SAHAB, TVS XL SUPER HEAVY DD CS.No. 3 AP11AA2852 0D1P61884927 MD621BD1862P54077 Pending 18-7-425/164,SIDDIQ NAGAR, BHAVANI DUTY – 2006 379/15 (2015) NAGAR HYDERABAD HERO HONDA CBZ X- DD CS.No. SRISAILAM SREE S/o NARSHIMHA r/o 3-92, 4 AP13S5203 KC12EBAGK00419 MBLKC12ECAGK00541 Pending TREME - 2010 485/15 (2015) DOMADUGU, BONTHAPALLI,JINNARAM DD CS.No. 5 BAJAJ BOXER CT – 2004 AP29D9116 DUMBLD16217 DUFBLD73427 Pending Records Not Found as per third eye 646 /15 (2015) SATYANARAYANA REDDY K s/o HERO HONDA SPLENDOR DD CS.No. 6 AP15AL2637 HA10EA89H08103 MBLHA10EE89H07756 Pending HANUMANTHA REDDY R/o 3-7-341, + 672/15 (2015) VAVILALAPALLY, KARIMNAGAR PULSAR 180 DTS-I BSIII - DD CS.No. Bhaskar Thanniru R/o H.NO. 30/88/12/16 7 AP10AV8245 DJGBT76288 MD2DHDJZZTCG33689 Pending 2010 962/15 (2015) Shiva Nagar Khanaji Guda Thirumalghirry JAI SANKAR A S/o RAGHAVULU R/o H NO 9- BAJAJ PULSUR 150 DTSI DD CS.No. -

Study and Collection of Hakku Patras and Other Documents Among Folk Communities in Andhra Pradesh

EAP201: Study and collection of Hakku Patras and other documents among folk communities in Andhra Pradesh Dr Thirmal Rao Repally, Potti Sreeramulu Telugu University 2008 award - Pilot project £10,261 for 12 months This survey gives an in-depth look at the function of Hakku Patras amongst the folk communities of Andhra Pradesh. It gives a brief account of the methodology of the survey and finally lists the artefacts that were discovered. Further Information You can contact the EAP team at [email protected] EAP-201 SURVEY REPORT On Hakku Patras among the Performing Communities of Andhra Pradesh The period of the Project 1 September 2008 to 31 August 2009 Submitted by Principal Investigator R. Thirmal Rao, Ph.D. Director, Andhra Pradesh Government Oriental Manuscripts Library and Research Institute, Behind O.U. Police Station, O.U. Campus, Hyderabad – 500 007. Andhra Pradesh. INDIA. Mobile : +91-9848794939 E-mail : [email protected] 1 C O N T E N T S Page No. 1. Introduction - 3 2. Location of Andhra Pradesh in India (Map) - 5 3. Andhra Pradesh (Map) - 6 4. Notes on Performing Communities - 7 1) General Folk Performances - 7 2) Particular Folk Performances - 8 3) Social Hierarchy of dependent or sub-caste - 9 5. What is Hakku Patras - 13 6. About the Project - 14 7. Details of Survey Methodology - 15 1) Field Work Plan - 17 2) Problems in Field Work - 17 3) Gathering information from other sources - 19 8. Condition of the Hakku Patras - 20 9. Photographing the Hakku Patras - 21 10. Copyright - 22 11. Number of families contacted - 24 12. -

Key Takeaways on 1ST Day of Webinar

K EY TAKEAWAYS On Collaborative Webinar Training Programme On Integrating Disaster Management Plan With Gram Panchayat Development Plan National Institute of Rural Development & Panchayati Raj Rajendrana, Hyderabad & National Institute of Disaster Management, MHA, New Delhi Key takeaways on 1ST day of Webinar. 1. Why we need to focus on disaster management plan? Since the intensity of disaster are increasing due to climate change and India is more prone to disaster because of its location. Disaster management plan launched in 2005 has provided a constitutional framework for to prepare the plan at gram panchayat, block level, district, state and central levels. As per the article 243 Z D of the constitution when the disaster management plan are being prepared by three layers of Panchayat Raj Institution, but the role of stakeholder preparing the disaster management plan in very minimal. More over many of the states are not in the Gram Panchayat as well as village committee in preparing the village disaster management plan. The major takeaway of this webinar would be that since the government is focusing on Gram Panchayat Development Plan which should include the Disaster Management Plan. Our main focus should be involving more public and community to plan for their disasters especially during emergencies. 2. Discussion of roles of various stakeholder integrating disaster management plans into gram panchayat development plan. 3. How the participants can mobilize the people and utilize the disaster management plan was one of the major objectives of the webinar 4. The participants were taught to make vulnerability and hazard assessment map with respect to COVID-19 in the participants area 5. -

District Wise Bcs List

District Wise BCs List S.NO BANK NAME District VILLAGE NAME OF BANK MITRA/BC/BF Contact number 1 BANK OF BARODA ADILABAD ADILABAD VODNALA NARESH 9533202654 2 BANK OF BARODA ADILABAD MANCHERIAL, ANDHRAPRADESH VINAY AGARWAL 9985657613 3 BANK OF BARODA ADILABAD ADILABAD POOSALA SADANANDAM 9948024538 4 BANK OF BARODA ADILABAD MANCHERIAL, ANDHRAPRADESH M LALITHA 9550969352 5 BANK OF BARODA ADILABAD MANCHERIAL, ANDHRAPRADESH P RAMA 8522818545 6 BANK OF INDIA ADILABAD ADILABAD B SATISH 7 CANARA BANK ADILABAD Hashimpet Palepu Devanna 9177345221 8 CANARA BANK ADILABAD Piporwada Palepu Devanna 9177345221 9 CANARA BANK ADILABAD Pusai Palepu Devanna 9177345221 10 CANARA BANK ADILABAD Bhoraj K Mahender Reddy 9866881666 11 CANARA BANK ADILABAD Fouzpur K Mahender Reddy 9866881666 12 CANARA BANK ADILABAD Pusai K Mahender Reddy 9866881666 13 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD CHINTHAPALLE S.TIRUPATHI REDDY 9912418621 14 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD DHARMARAM SURESH 9490101900 15 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD PAIDPALLE JADI VINAY 9490874215 16 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD PEDDAPUR KESHAV 8008062180 17 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD LEMUR VELPULA LAVANYA 9866042596 18 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD MALEGAON S. RAMESH 7893946876 19 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD LINGAPUR S.SRINIVAS 8374195186 20 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD MITTAPALLY K.JANARDHAN 9989164421 21 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD AMERWADI BANDDI SRIDHAR 8897577390 22 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD CHANDRAPALLE THIRUPATHI 9963839149 23 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD SHAKARI P.SRINIVAS 9492371752 24 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD GONDI BHAGYALAKSHMI - 25 ANDHRA BANK ADILABAD GARLAPET N.PRAVEEN 9542721242 26 ANDHRA -

Integrated Socioeconomic and Geospatial Attributes to Distinguish Infrastructure Quandaries in Medchal Mandal, India

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Integrated socioeconomic and geospatial attributes to distinguish infrastructure quandaries in Medchal Mandal, India D. Naresh Kumar Department of Civil Engineering St. Martin’s Engineering College, Secunderabad,Telangana, India Dr. T. Madhu Department of Geology Sri Venkateshwara university, Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, India Abstract- Socioeconomic assessment and supervision require an immense quantity of information. Moderately huge capacities of multi-disciplinary and scientific data have to be composed, progressed, analyzed, and ultimately communes of population data. Socio and environment communication have been foremost unease in urban region in that combined with socio economic and geospatial research to resolve the quandary. Geospatial techniques have been experiential to have an impending systematic assessment for the study of human activity on Medchal Mandal. Interpolation and choropleth analysis of Geospatial methodology used in this research paper. The Choropleth maps exhibit the Medchal (Urban), Gundlapochampalle, and Dabilpur regions are well developed due to good connectivity of infrastructure, remain villages have to be developed by the connection of networks with quantitative represent. Interpolation analysis shows spatial spreading sheets without numerical values. This research executes the Medchal Mandal human population increases rapidly consequently major change undergone profound such as household population, literacy, employability, infrastructure -

Sc/St Backlog -2018)

PROVISIONAL COMMON LIST OF JUNIOR ASSISTANTS (SC/ST BACKLOG -2018) Local / Application Name of the Father / Qualification Total Marks Percentag Male/ Mobile Date of Birth Caste Non District Full Address of the applicant DISTRICT Remarks Sl.No. Applicant Spouse Name ( Category ) Marks obtained e Female Number Local H.NO 7-65/3/2, VIDYANAGAR, 1 UYKE YOGESHWER BALIRAM 05.08.1991 B.Pharmacy 6025 3490 57.93 M ST Local Adilabad BESIDE SATOSHIMATHA TEMPALE ADILABAD 9533378080 ICHODA, ADILABAD H.NO 1-1-86 NEAR ERODRAM SRI MAMIDI VAISHALI LAXMAN 10.06.1995 B.Sc 2200 1601 72.77 F SC Local Adilabad ADILABAD 9059386119 2 RAM COLONY ADILABAD H.NO 2-104/12, VILL & MDL BALIRAM A VITTAL 15.06.1986 B.Sc 2200 1105 50.23 M ST Local Adilabad ADILABAD 7993792754 3 BHEEMPUR DIST ADILABAD MUKKERA MUKKERA H.NO 4-65 VILL PENDALWADA I TO X BONAFIDES NOT 13.01.1996 B.Sc 2200 1383 62.86 M SC Local Adilabad ADILABAD 9676515592 4 SANTOSH BORRANNA MDL JAINATH ADILABAD SUBMITTED KUMRA ANIL KUMRA KESHAV H.NO 1-11 VILL CHINCHUGHAT, 20.06.1994 BA 1600 679 42.44 M ST Local Adilabad ADILABAD 7013965771 5 KUMAR RAO ADILABAD H.NO 8-29, VILL SHANKAR TANDA I TO IV BONAFIDES NOT 6 JADHAV SATEESH JADHAV BHIKKU 03.05.1992 B.Tech 5200 2962 56.96 M ST Local Adilabad HASNAPUR MDL UTNOOR ADILABAD 9542906066 ADILABAD SUBMITTED T. SARVESHWAR H.NO 2-4-267/1, KOLIPURA I TO III BONAFIDES NOT T.SRINIVAS 12.02.1985 BA 1600 781 48.81 M SC Local Adilabad ADILABAD 9949867303 8 RAO COLONY ADILABAD SUBMITTED MANDA PRAVEEN H.NO 4-106 VILL KONDAPUR MDL SHANKAR 03.08.1989 B.Com 1900 942 49.58 M SC