Why US Hard Currency Is Worrying Affluent Australians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

147 Chapter 5 South Africa's Experience with Inflation: A

147 CHAPTER 5 SOUTH AFRICA’S EXPERIENCE WITH INFLATION: A CENTRAL BANK PERSPECTIVE 5.1 Introduction Although a country’s experience with inflation can be reviewed from different perspectives (e.g. the government, the statistical agency responsible for recording inflation, producers, consumers or savers), this chapter reviews South Africa’s experience with inflation from the perspective of the SA Reserve Bank. The SA Reserve Bank was chosen because this study focuses on inflation from a monetary perspective. Reliable inflation data for South Africa are published as far back as 192153, co-inciding with the establishment of the SA Reserve Bank, although rudimentary data on price levels are available as far back as 1895. South Africa’s problems with accelerating inflation since the 1970s are well documented (see for instance De Kock, 1981; De Kock, 1984; Republiek van Suid-Afrika, 1985; Rupert, 1974a; Rupert, 1974b; or Stals, 1989), but various parts (or regions) of what constitutes today the Republic of South Africa have experienced problems with inflation, rising prices or currency depreciation well before 1921. The first example of early inflation in South Africa was caused by currency depreciation. At the time of the second British annexation of the Cape in 1806, the Dutch riksdaalder (“riksdollar”) served as the major local currency in circulation. During the tenure of Caledon, Governor of the Cape Colony from 1807 to 1811, and Cradock, Governor from 1811 to 1814, riksdollar notes in circulation were increased by nearly 50 per cent (Engelbrecht, 1987: 29). As could be expected under circumstances of increasing currency in circulation, the value of the riksdollar in comparison to the British pound sterling and in terms of its purchasing power declined from 4 shillings in 1806 to 1 shilling and 5½ pennies in 1825 (or 53 Tables A1 to C1 in Appendices A to C highlight South Africa’s experience with inflation, as measured by changes in the CPI since 1921. -

USA Metric System History Pat Naughtin 2009 Without the Influence of Great Leaders from the USA There Would Be No Metric System

USA metric system history Pat Naughtin 2009 Without the influence of great leaders from the USA there would be no metric system. Since many in the USA do not believe this statement, let me repeat it in a different way. It is my belief that without the influence of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington, the metric system would not have developed in France in the 1780s and 1790s. The contribution made by these three great world leaders arose firstly from their cooperation in developing and implementing the idea of a decimal currency for the USA. The idea was that all money could be subdivided by decimal fractions so that money calculations would then be little more difficult than any normal whole number calculation. In 1782, Thomas Jefferson argued for a decimal currency system with 100 cents in a dollar. Less well known, he also argued for 1000 mils in a dollar. Jefferson reasoned that dividing America's First Silver Dollar decimally was the simplest way of doing this, and that a decimal system based on America's First Silver Dollar should be adopted as standard for the USA. The idea of using decimal fractions with decimal numbers was not new – even in the 1780s. Thomas Jefferson had studied 'Disme: the art of tenths' by Simon Stevin in which the use of decimals for all activities was actively promoted. Stevin proposed decimal fractions and their decimal arithmetic for: ... stargazers, surveyors, carpet-makers, wine-gaugers, mint-masters and all kind of merchants. Clearly Simon Stevin had in mind the use of decimal methods for all human activities and it is likely that this thought inspired Thomas Jefferson to propose not only a decimal currency for the USA but also a whole decimal method for weights and measures. -

1 from the Franc to the 'Europe': Great Britain, Germany and the Attempted Transformation of the Latin Monetary Union Into A

From the Franc to the ‘Europe’: Great Britain, Germany and the attempted transformation of the Latin Monetary Union into a European Monetary Union (1865-73)* Luca Einaudi I In 1865 France, Italy, Belgium and Switzerland formed a monetary union based on the franc and motivated by geographic proximity and intense commercial relations.1 The union was called a Latin Monetary Union (LMU) by the British press to stress the impossibility of its extension to northern Europe.2 But according to the French government and many economists of the time, it had a vocation to develop into a European or Universal union. This article discusses the relations between France, which proposed to extend the LMU into a European monetary union in the 1860’s, and the main recipients of the proposal; Great Britain and the German States. It has usually been assumed that the British and the Germans did not show any interest in participating in such a monetary union discussed at an international monetary Conference in Paris in 1867 and that any attempt was doomed from the beginning. For Vanthoor ‘France had failed in its attempt to use the LMU as a lever towards a global monetary system during the international monetary conference... in 1867,’ while for Kindleberger ‘the recommendations of the conference of 1867 were almost universally pigeonholed.’3 With the support of new diplomatic and banking archives, together with a large body of scientific and journalistic literature of the time, I will argue that in fact the French proposals progressed much further and were close to success by the end of 1869, but failed before and independently from the Franco-Prussian war of 1870. -

UK FINANCIAL HISTORY 1950 – 2015 Version FEBRUARY 2016 Operator Info

Document Info Notes Form SW55063 Job ID 57630 Size A4 Pages 1 Colour CMYK UK FINANCIAL HISTORY 1950 – 2015 Version FEBRUARY 2016 Operator Info 1 ALI 29/02/16 2 ALI 07/03/16 Barclays Equity Index £156,840 3 Dividends Reinvested 4 5 £100,000 6 Big Bang in the city London Olympics Interest rates hit 15% • 7 Northern Rock crisis • • 8 ECONOMIC INDICATORS Berlin Wall comes down Japanese• earthquake • • 9 30 Unemployment tops 3 million Bangladesh factory disaster RPI – annual % change (quarterly) • • 10 Stockmarket hits 62 England, Wales, Northern Ireland introduce smoking ban • Lockerbie disaster • 11 25 Bank base rates (quarterly avg.) • Scotland introduces smoking ban Bin Laden killed • • 12 First test tube baby born 20 GDP – annual % change (quarterly) • • ‘Black Wednesday’ stockmarket crisis Banking debt crisis hits UK Nelson Mandela dies 13 • • 14 15 London wins Olympic bid Greek bail-outs • UK gets £2,300 million from IMF • Single European Market begins • • 15 UK Interest Rates set at 0.5% Ebola outbreak Barclays Equity Price Index 10 • £9,558 £10,000 • Ex-Dividends Proof number 1 2 3 4 Barclays Gilt Index 5 Japanese interest rates at record low of 0.5% £8,631 • Ceasefire in Vietnam • Income Reinvested Mandatory checks 0 Poll Tax riots Hong Kong handover Plaza accord • Cyprus bail-out £5,554 UK Building Society Index • • • Income Reinvested -5 UK joins EEC News of World closes New Brand - use approved template (check size) • • War in Iraq Cuba/US• reconciliation Falklands War • • £3,058 Retail Prices Index Footer/Form number/version -

The Bank of England and Earlier Proposals for a Decimal ,Coinage

The Bank of England and earlier proposals for a decimal ,coinage The introduction of a decimal system of currency in Febru ary 1971 makes it timely to recall earlier proposals for decimalisation with which the Bank were concerned. The establishment of a decimal coinage has long had its advocates in this country.As early as 1682 Sir William Petty was arguing in favour of a system which would make it possible to "keep all Accompts in a way of Decimal Arith metick".1 But the possibility of making the change did not become a matter of practical politics until a decade later, when the depreciated state of the silver currency made it necessary to undertake a wholesale renewal of the coinage. The advocates of decimalisation, including Sir Christopher Wren - a man who had to keep many 'accompts' - saw in the forthcoming renewal an opportunity for putting the coin age on a decimal basis.2 But the opportunity was not taken. In 1696 - two years after the foundation of the Bank - the expensive and difficult process of recoinage was carried through, but the new milled coins were issued in the tra ditional denominations. Although France and the United States, for different reasons, adopted the decimal system in the 18th century, Britain did not see fit to follow their example. The report of a Royal Commission issued in 1819 considered that the existing scale for weights and measures was "far more con venient for practical purpose,s than the Decimal scale".3 The climate of public opinion was, however, changing and in 1849 the florin was introduced in response to Parliamentary pressure as an experimental first step towards a decimal ised coinage. -

The Irish Pound from Origins To

Quarterly Bulletin Spring 2003 The Irish Pound: From Origins to EMU by John Kelly* ABSTRACT The history of the Irish pound spans seventy-five years, from the introduction of the Saorsta´t pound in 1927 to the changeover to euro banknotes and coin in 2002. For most of this period, the Irish pound had a fixed link to sterling. It was only in the 1970s that this link was seriously questioned when it failed to deliver price stability. This article provides a brief overview of the pound’s origins, before looking in more detail at the questioning of the sterling link and events leading up to Ireland joining the EMS. Although early experiences in the EMS were disappointing, membership eventually delivered low inflation, both in absolute terms and relative to the UK, and laid the foundations for the later move to EMU. The path to EMU is followed in some detail. This covers practical preparations, assessment of benefits and costs and necessary changes in monetary policy instruments and legislation. Finally, the completion of the changeover encompasses the huge tasks of printing and minting sufficient amounts of euro cash, of distributing this to banks and retailers, and of withdrawing Irish pound cash, as well as the efforts of all sectors to ensure that the final changeover from the Irish pound to the euro was smooth and rapid. 1. Introduction The Irish pound ceased to be legal tender on 9 February 2002. This brought down the final curtain on a monetary regime which had its origins some 75 years earlier with the introduction of the Saorsta´t pound in 1927. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Cook, Andrew J. Britain’s Other D-Day: The Politics of Decimalisation Original Citation Cook, Andrew J. (2020) Britain’s Other D-Day: The Politics of Decimalisation. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/35268/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ BRITAIN’S OTHER D-DAY: THE POLITICS OF DECIMALISATION ANDREW JOHN COOK A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield March 2020 CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………. 2 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………………… 6 Chapter 2: Political Management…………………………………………………….. 50 Chapter 3: Britishness and Europeanisation…………………………………….. 92 Chapter 4: Modernity, Declinism and Affluence………………………………. 128 Chapter 5: Interest Groups………………………………………………………………. -

Practical Issues Arising from the Euro May 2002

Practical issues arising from the euro May 2002 Bank of England Practical issues arising from the euro Practical issues arising from the euro May 2002 05 FOREWORD 07 SUMMARY 15 PART I: COMPLETION OF THE EURO CHANGEOVER IN PRACTICE 15 The euro area 24 Austria 29 Belgium 34 Finland 38 France 44 Germany 49 Greece 53 Ireland 60Italy 65 Luxembourg 69 The Netherlands 74 Portugal 78 Spain 84 PART II: LESSONS FROM THE EURO CHANGEOVER 84 A: THE ORGANISATION OF THE CHANGEOVER 85 B: THE COMPLETION OF THE NON-CASH CHANGEOVER 86 Box: Lessons from the conversion weekend 87 Accounts 90Payments 92C: THE CASH CHANGEOVER 92 Prior distribution of euro cash 94 Box: Frontloading: payment and collateral 96 Box: Contrasting approaches to sub-frontloading 97 Starter kits 100 Cash at banks 103 Cash at retailers 104 Cash for tickets and vending machines 105 Withdrawal of legacy cash 106 Box: Contrasting approaches to the withdrawal of legacy cash 107 Box: Defacement of legacy banknotes 108 D: COSTS AND BENEFITS OF A QUICK CHANGEOVER 108 The timetable for the changeover 110The pace of the cash changeover 111 Box: Why was the cash changeover quicker in some countries than others? 112 Costs and benefits of a quick cash changeover Practical Issues Arising from the Euro: May 2002 3 114 E: OTHER ISSUES 114 The prevention of criminal activity 116 The information campaign 117 The attitude of the public 118 The impact on prices 119 Box: Euro-area HICP: evidence of euro changeover effects 120Changeover costs and charges 124 PART III: LESSONS FOR THE UK 124 A: SIMILARITIES -

Britain and the Pound Sterling

Britain and the Pound Sterling! !by Robert Schneebeli! ! Weight of metal, number of coins For the first 400 years of the Christian era, England was a Roman province, «Britannia». The word «pound» comes from Latin: the Roman pondus was divided into twelve unciae, which in turn gives us our English word “ounce”. In weighing precious metals the pound Troy of 12 ounces is used, 373 grams in metric units. In France, instead of pondus, the Latin word libra, weighing- scales, was used instead, so that «pound» in French is livre. That is why, when we weigh meat, for example, and want to write seven pounds, we write 7 lb., as if we were saying librae instead of pounds. And if we’re talking about pounds in the monetary sense, we also use a sign that reminds us of the Latin libra – the pounds sign, £, is actually only a stylised letter L. In the 8th century, in the age of King Offa in England or of Charlemagne in Europe, when the English currency began to be regulated, it was not the pound that was important, but the penny. The origin of the word «penny», and how it came to mean a coin, is obscure. A penny was a small silver coin – for coinage purposes silver was more important than gold (for example, the French word for money, argent, comes from argentum, the Latin for silver). Alfred the Great, the most famous of the Anglo-Saxon kings, fixed the weight of the silver penny and had pennies minted with a clear design. -

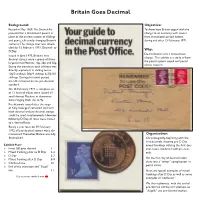

Britain Goes Decimal

Britain Goes Decimal Background: Objective: Passed in May 1969, The Decimal Act To show how Britain coped with the provided for a decimalised pound, in change to its currency with covers place of the ancient system of shillings from transitional period, before, and pence, effectively changing Britain’s during and after 15 February 1971. currency. The change over was sched- uled for 15 February 1971, Decimal- or D Day. Why: Decimalisation was a momentous Issued in June 1970, Britain’s first change. This exhibit is a study of how decimal stamps were a group of three the postal system coped and postal large-format Machins: 10p, 20p and 50p. clients reacted. Easing the transition, each of these was directly equivalent in shilling terms: 10p/2 shillings; 20p/4 shillings & 50p/10 shillings. During this initial period, the UK remained on the pre-decimal standard. On 15 February 1971, a complete set of 12 decimal values were issued, all small-format Machins, in denomina- tions ranging from ½p to 9p. Pre-decimals issued after the reign of King George V remained valid and both decimal and pre-decimal stamps could be used simultaneously. However, following D Day, all rates were moved to a decimal basis. Barely a year later, on 29 February 1972, all pre-decimal stamps were de- monetized. Thereafter, Britain was fully Organization: decimalised. Chronologically-beginning with the first decimals, showing pre-D Day Exhibit Plan– mixed frankings utilising the first dec- » Intro: GB goes decimal 1 imal issues combined with pre-deci- » Mixed franking prior to D Day 2-4 mals. -

The Metrical System of Weights and Measures Author(S): Alex

The Metrical System of Weights and Measures Author(s): Alex. Siemens Source: Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Vol. 66, No. 4 (Dec., 1903), pp. 688-719 Published by: Wiley for the Royal Statistical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2339493 . Accessed: 24/06/2014 21:22 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley and Royal Statistical Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 62.122.78.91 on Tue, 24 Jun 2014 21:22:47 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 688 roDec. The MAETRICAL,SYSTEM of AVEIGIhTS and MEASURES. -ByALEX. SIEMENS. [Read beforetje Royal StatisticalSociety, 15th December,1903. MAJOR PATtICE GEORGE CRAIGIE, C.B., President,in the Chair.] IN the " Notes oil the MletricalSystem of Weights and Measures," which were discussed in the beginiiiligof this year at two meetings of the Institutioll of Electrical Enigineers,the origin of the metrical system is fully described, but it will not be superfluousjust to recapitulate the leadiiig features of its history. For a long time scientificmen ill various countrieshad recognisedthe desirabilityof carryingon their investigationisin accordance with international units of weights aild measures, subdivided in a uniformmanner, but no action is recorded until James Watt took up the subject in 1783; and there is verylittle doubt that the presentmetrical system is the outcome of his agitation. -

Maurice O'connell: the Euro Changeover in the Irish Context

Maurice O'Connell: The euro changeover in the Irish context Statement by Mr Maurice O'Connell, Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland, to the Irish Parliamentary Joint Committee on Finance and the Public Service, in Dublin on 18 July 2001. * * * Chairman We are now less than six months away from the launch of euro banknotes and coin, three years after the introduction of the euro as a currency. The period of transition has been very long but this has been unavoidable because of the complex production and distribution process that is required. The euro will at last become a fully fledged currency on 1st January. For the first time the public in general will be able to relate to it as their own currency. This should have a very positive impact in terms of gaining acceptance of the new currency. The changeover is a big undertaking for all countries of the euro area. The individual national central banks have worked closely together through the European System of Central Banks. There has been regular monitoring of production to ensure uniform quality of banknotes across the euro area. The overall production requirement for launch of the new currency is 15 billion banknotes and 50 billion coins. These figures are so large as to be almost incomprehensible. Each national central bank is charged with the responsibility of meeting requirements in its own country. In our case this means that we will provide more than 200 million banknotes and more than 1,000 million coins. Members of this Committee will be familiar already with the banknote and coin denominations and the conversion rate against the Irish pound.