Mainstreaming the Urban Poor. Enabling Non-Public Schools To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LVC FY13 Annual Report

BUILDING COMMUNITY V LIVING SIMPLY & SUSTAINABLY WORKING FOR JUSTICE H BUILDING COMMUNITY V LIVING SIMPLY & SUSTAINABLY WORKING FOR JUSTICE H BUILDING COMMUNITY V LIVING SIMPLY & SUSTAINABLY WORKING FOR JUSTICE H BUILDING COMMUNITY V LIVING SIMPLY & SUSTAINABLY WORKING FOR JUSTICE H BUILDING COMMUNITY V LIVING SIMPLY & SUSTAINABLY WORKING FOR A YEAR OF LUTHERAN SERVICE VOLUNTEER a lifetime of CORPS commitment 2013 ANNUAL REPORT THE EVOLUTION OF SERVICE STATEMENT OF ACTIVITIES LVC BOARD OF Dear friends, September 1, 2012 - August 31, 2013 DIRECTORS : Combined Financial Statements for Lutheran Volunteer History will show what an amazing era of change we are experiencing now. 2013 & 2014 Corps and the Lutheran Service Corps In the last six years we have elected our first black President, secured rights PROGRAM YEARS and growing acceptance for the GLBT community, extended health care to millions of people who until recently were uninsured, and experienced the OPERATING REVENUE FY13 FY12 Bruce Albright * growing electoral strength of people of color. Nancy Appel, Board Chair * These changes seemed out of reach to me when I was getting my start in the Program Fees $763,588 $794,249 social justice movement years ago. For example, in the attempt to officially Housing $789,616 $757,104 Emried (Em) D. Cole, Jr. allow our gay and lesbian brothers and sisters to serve openly in the military 2,595 Contributions $389,084 $369,582 Doug Cutchins * in 1994, we got “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”, an official “you’d better stay in the Contributed Services $3,066 $19,535 closet” proclamation! And health care reform didn’t get even that far. -

2017Annual Report

20172017 Annual Report Lutheran Volunteer Corps staff list A.J. CABRERA | Program Manager - Admissions TAIT DANIELSON CASTILLO | Major Gifts Officer (Alum, Baltimore 1998-1999), Interim President NATHAN DETWEILER | Community Outreach and Development Associate (Alum, DC 2016-2017) ERIKA DORNFELD | Program Manager – Midwest Region (Alum, Chicago 2009-2011) REV. ELIZABETH BIER | Recruitment & Outreach Manager (Alum, Twin Cities 2002-2004) SOPHIE GARDNER | Program Manager – West Region (Alum, Seattle 2010-2011) SCOTT GLASER | Development & Community Outreach Manager JULIE HAMRE | Comptroller (Volunteer Staff) DEIRDRE KANZER | Program Manager – Midwest Region KELSEY KAUFFMAN | Program Manager – East Region JUDY KUHAGEN | Staff Volunteer DREA MAST | Business Operations Manager ERIN PERRY | Communications & Development Associate (LVC Volunteer JACK SIEFERT | Program Manager – Puget Sound (Alum, DC 1984-1985) LVC Board of Directors Fiscal Year 2017 REV. JUSTIN ASK CARRIE CARROLL ROBERT (BOB) CLAUSEN* EMORY ELLIOT* BILL FUSON* GARY GEORGE* | Secretary BRANDEN GRIMMETT* MATTHEW JAMES* JULIE KLEIN* NATHAN MILLER* | Treasurer EMERSON WILLIAMS-MOLLETT* JEFF YAMADA* | Chair *Current Board Member Peace. It does not mean to be in a place where there is no noise, trouble or hard work. It means to be in the midst of these things and still be calm in your heart. – UNKNOWN Dear Friends, Within this report, you’ll find many things – the stories of two big changes and transitions of the last year, the story of a wonderful alum, whose life is now honored through a scholarship to support the placements and nonprofits of greatest need, and both photos and stories from those following in the footsteps of many of you – our current Volunteers. As we journey through these transitions, we can’t help but remember our roots. -

Handbook For

Handbook for 2016-17 Handbook for Jesuit Volunteers/AmeriCorps Members TABLE OF CONTENTS Mission Statement and History of the JVC Northwest 3 The Covenant of JVC Northwest 4 The JVC Northwest Year 6 The JVC Northwest Staff 7 Expectations of the JV/AmeriCorps Member 11 Relationship with Partner Agencies 14 Communities by Program Coordinator 15 Retreat Program 16 The Role of the Program Coordinator 17 Local Community Support for JVs 17 Personal and Communal Policies and Best Practices 19 Car Policy 21 End of the Year 21 Money Matters: Fiscal Structure of JVC Northwest Households 22 Housing and Good Neighbor Policies and Best Practices 26 Emergency Procedures 31 Living in Community 32 Approaches to Community Meetings 33 Roles in Community 34 Race in Community 35 Critical Issues: Awareness and Response 37 Drug and Alcohol Policy 38 Code of Conduct 39 Grievance Procedure 50 2 WELCOME! JESUIT VOLUNTEER CORPS NORTHWEST MISSION STATEMENT Jesuit Volunteer Corps (JVC) Northwest responds to local community needs in the Pacific Northwest by placing volunteers who provide value-centered service grounded in the Jesuit Catholic tradition. Honoring the Divine at work in all things, we envision the Northwest as a sustainable region where all live in dignity, are treated justly, and actively contribute to their own empowerment and positive change in their communities. JVC Northwest strives to live out the four values of community, simple living, social and ecological justice, and spirituality/reflection. HISTORY OF THE JESUIT VOLUNTEER CORPS NORTHWEST Jesuit Volunteer Corps (JVC) Northwest began in 1956 with a few committed volunteers who helped build and teach in the new Copper Valley School in Copper Valley, Alaska, a boarding school for Native Alaskan and European-descent Alaskan students. -

LVC FY14 Annual Report

Lutheran Volunteer Corps Annual Report 2015 Building Communities of Peace with Justice If you have come here to help me, you are wasting our time. But if statement of Activities you have come because your liberation SEPTEMBER 1, 2013—AUGUST 31, 2014 is bound up with mine, Combined Financial Statements for Lutheran Volunteer Corps and then let us work together.” the Lutheran Service Corps OPERATING REVENUE FY14 FY13 Program Fees $795,122 $763,588 THIS QUOTATION, credited to Lilla Watson, has been on the Housing $820,595 $789,616 back of the LVC t-shirts given to our Volunteers at orientation Contributions $296,393 $389,084 for many years. Ms. Watson calls us to participate in the jus- Contributed Services $3,000 $3,066 tice movement in an entirely different modality. She asks us Other Revenue $154,149 $23,538 if we believe that we are bound to one another. TOTAL INCOME $2,069,259 $1,968,892 She asks us to stop seeing ourselves as helpers or those being helped; as oppressors or the oppressed; as a one per- OPERATING EXPENSES FY14 FY13 center or the 99 percent. Much like Martin Luther King, Jr. Program $1,772,338 $1,580,053 in a letter from a Birmingham jail in which he wrote, “a threat to justice anywhere is G&A $103,253 $104,629 a threat to justice everywhere,” she invites us to find and experience our common Fundraising $154,789 $154,789 humanity and the connection between us—for we have far more commonalities than Total Expense $2,030,380 $1,839,471 differences. -

View the Viking Update

Honoring Tradition EMBRACING CHANGE CLASS OF ST. OLAF COLLEGE Class of 1969 – PRESENTS – The Viking Update in celebration of its 50th Reunion May 31 – June 2, 2019 Autobiographies and Remembrances of the Class stolaf.edu 1520 St. Olaf Avenue, Northfield, MN 55057 Advancement Division 800-776-6523 Student Editors Joshua Qualls ’19 Kassidy Korbitz ’22 Matthew Borque ’19 Student Designer Philip Shady ’20 Consulting Editor David Wee ’61, Professor Emeritus of English 50th Reunion Staff Members Ellen Draeger Cattadoris ’07 Cheri Floren Michael Kratage-Dixon Brad Hoff ’89 Printing Park Printing Inc., Minneapolis, MN Welcome to the Viking Update! Your th Reunion committee produced this commemorative yearbook in collaboration with students, faculty members, and staff at St. Olaf College. The Viking Update is the college’s gift to the Class of in honor of this milestone year. The yearbook is divided into three sections: Section I: Class Lists In the first section, you will find a complete list of everyone who submitted a bio and photo for the Viking Update. The list is alphabetized by last name while at St. Olaf. It also includes the classmate’s current name so you can find them in the Autobiographies and Photos section, which is alphabetized by current last name. Also included the class lists section: Our Other Classmates: A list of all living classmates who did not submit a bio and photo for the Viking Update. In Memoriam: A list of deceased classmates, whose bios and photos can be found in the third and final section of the Viking Update. Section II: Autobiographies and Photos Autobiographies and photos submitted by our classmates are alphabetized by current last name. -

This Project Will Expand Our Services, and Make the Beacon Hill Neighborhood a Destination for All Residents of King County and the State of Washington

Lutheran Volunteer Corps - Open Positions as of 6/1/16 www.lutheranvolunteercorps.org Placement Position Title Organization LVC City Program Assistant for Marketing and Creative Services - Lutheran World Relief Lutheran World Relief Baltimore, MD Primary Area of Concern International Solidarity Secondary Area of Concern Multi-Category The Program Assistant for Marketing and Creative Services is an integral part of the Marketing and Creative Services unit at LWR. The position supports the unit’s efforts to provide leadership in communication strategy and key message development for engaging LWR’s target U.S. audiences and to create high- quality, effective, engaging and audience-centric communication tools that build LWR’s relationship with its audiences. Core responsibilities include: Support the management of marketing and communication projects across the organization by scheduling project meetings, keeping up to date project meeting notes and updating LWR’s project management system. Draft and edit content for LWR communications including the print newsletter, electronic newsletter and blog. Support LWR’s social media strategy by monitoring Facebook and Twitter, and drafting and posting content. Track media coverage of LWR and maintain database of media hits. Assist with keeping website content up to date. Aid in monitoring LWR’s brand identity across media. Research new opportunities for LWR to engage with its current constituency and engage new constituents. Manage LWR’s policy for ordering promotional products and LWR-branded gear -

Lauren Andres United States Navy Joshua Barrett United States Army

Please join us in praying for the following students, and all those of whom we may not be aware, who are entering the priesthood or religious life, Military service or volunteering at least one year of their lives in service to others: MILITARY SERVICE Christopher Huben Amate House Lauren Andres Chicago, Illinois United States Navy Christopher Kramer Joshua Barrett PLACE Corps United States Army Los Angeles, California John Brewer James Lewis United States Army Americorps Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Douglas Donatelli Meredith O’Connell United States Navy Lutheran Volunteer Corps Washington, District of Columbia Patricia Nolan United States Army Rhiannon Richards Salesian Lay Missionaries Bolivia Molly Rodahaver United States Army Monica Rivera Alliance for Catholic Education Collin Roszyk New York, New York United States Army Michael Thorsen Justin Shuma Rostro de Cristo United States Marine Corps Ecuador James Wronksi Kathryn Vidrine AmeriCorps VISTA United States Air Force Milwaukee, Wisconsin PRIESTHOOD OR RELIGIOUS LIFE LONG-TERM SERVICE Anthony Carone Briana Bee Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston Lutheran Volunteer Corps Seattle, Washington Cecilia Cicone Daughters of St. Paul Haley Drier William Clingerman Rostro de Cristo Diocese of Trenton Ecuador Katherine Fournier Matthew Gatti Discalced Carmelites Jesuit Volunteer Corps Detroit, Michigan Patrick Gill Archdiocese of Baltimore Joseph Herlihy Christ the King Service Corps James Glasgow Archdiocese of Washington Detroit, Michigan Alison Gliot Daughters of St. Paul Joseph Moschetto Diocese of Arlington Matthew Norwood Archdiocese of Boston Julian Ortiz Archdiocese of Washington Peter Rubeling Archdiocese of Baltimore Tyler Santy Diocese of Syracuse Philip Stokman Fraternity of Saint Charles Borromeo Riley Winstead Diocese of Wilmington . -

Lutheran Volunteer Corps BUILDING COMMUNITY, WORKING for JUSTICE, LIVING SIMPLY and SUSTAINABLY

Lutheran Volunteer Corps BUILDING COMMUNITY, WORKING FOR JUSTICE, LIVING SIMPLY AND SUSTAINABLY Dear friends, Last year LVC, and its many service corps colleagues, experienced a drop in Volunteer participation in our programs, mostly as a result of the improving economy. Fortunately, one of the benefits of living sustainably as an organization, and going through an inclusive strategic planning process, is that our team banded together to make adjustments to remain present in all of our LVC cities while still leaning into our new direction. One aspect of the new direction includes deepening our partnerships with Lutheran churches that are leaning into LVC’s core practices of simple and sustainable living, intentional community, and serving for justice. We are excited that while accommodating lower Volunteer numbers, we have also become partners with three Milwaukee churches that are engaged in food justice efforts. This fall we will establish an LVC Food Justice House and program in the Milwaukee community. We are also re‐committing to living a Lutheran theology that celebrates the fact that God’s servants come from many faith traditions. We believe that we are more effective in creating peace with justice when we live and serve together as one body, and let our own community be transformed through this process. Alumna Sarah Cledwyn has helped LVC and its Volunteers lean into this belief by implementing the “Journeys Conversations” as the central component of LVC’s spirituality program. Each participant is encouraged to share their story about what calls them to serve and places the emphasis on curiosity and gaining shared meaning amongst participants. -

Choose Service Free for You Catholicvolunteernetwork.Org $3 for Us to Print

A DIRECTORY OF FULL-TIME, FAITH-BASED VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITIES RESPONSE2020 DISCOVER 150+ VOLUNTEER PROGRAMS LAURA'S REFLECTION CHOOSE SERVICE FREE FOR YOU CATHOLICVOLUNTEERNETWORK.ORG $3 FOR US TO PRINT. PLEASE CONSIDER MAKING A DONATION. Envision a Loving World Come live the vision! Paris - Baltimore - London - Lima - Dublin 410-442-3171 LifeAsASister.org Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps RESPONSE2020 Letter from the Executive Director 2 Alphabetical Listing of Volunteer Programs 9 Board of Directors 2 Volunteer Program Listings 10 About Catholic Volunteer Network 3 Volunteering and Vocation INSERT Partners for Service 4 Volunteer Reflection – Choose Service by Laura National Partner Organizations 5 Camarata, Farm of the Child, 2016-2019 INSERT CVN en Español 5 Index: Type of Service Placement 84 Ten Tips for Getting Started 6 Index: Service Locations 100 Continuing the Journey – Resources for Index: Length of Service 104 Former Volunteers 7 Index: Age Requirements 106 Connect 7 Index: Additional Preferences 108 Graduate School Opportunities 8 Next Steps 112 Catholic Volunteer Network | 6930 Carroll Ave. Suite 820 | Takoma Park, MD 20912 301-270-0900 | [email protected] COVER PHOTO: Mister Nemanja and Miss Annie, two BECA (Bilingual Education for Central America) volunteers, with their reading buddy at San Jeronimo Bilingual School in Cofradia, Honduras. Photo by Cody Hays. Letter from the Executive Director Dear Friend, Faith is about transformation. For 56 years, Catholic Volunteer Network (CVN) has been transforming individuals and communities through faith-based service and mission. We offer a range of experiences that empower volunteers and the people they support. You may be moved by the poverty you see in far-away lands or right in your own neighborhood. -

LVC FY11 Annual Report

LUTHERAN VOLUNTEER LUTHERAN CORPS VOLunteer CorpsFISCAL 2010 –YEAR 2011 ANNUA REPORTL REPORT 9/1/10 TO 8/31/11 BUILDING A STRONG FOUNDATION PAGE 1 | WWW.LUTHERANVOLUNTEERCORPS.ORG LUTHERAN VOLunteer Corps 2010 – 2011 ANNUAL REPORT Lutheran Volunteer Corps (LVC) is a national public service and leadership development organizaton that matches volunteers with full- time positions in social justice organizations for one year. LVC partners with more than 120 social justice organizations in 16 U.S. cities. 14 SEATTLE 6 TACOMA MILWAUKEE PORT HURON 5 4 WILMINGTON TWIN CITIES 22 3 13 DETROIT 9 OMAHA 6 20 BAY AREA CHICAGO BALTIMORE 11 WASHINGTON, DC 23 9 ATLANTA PAGE 2 | WWW.LUTHERANVOLUNTEERCORPS.ORG LUTHERAN VOLunteer Corps 2010 – 2011 ANNUAL REPORT Spirituality and LVC Journey to an Founded by Luther Place Memorial Inclusive Community Church in Washington, DC, Lutheran LVC holds an organization-wide com- Volunteer Corps is a Christian min- mitment to becoming an anti-oppres- istry steeped in Lutheran traditions sion organization by working towards and theology, but open to persons of dismantling racism, heterosexism, all faith traditions. Volunteers do not sexism and other oppression present need to be Lutheran or of any faith in our society and institutions. Volun- tradition, but are expected to share teers receive training and opportuni- their faith journeys, discern voca- ties for reflection tional direction and try on spiritual with a common lan- practices. The broader community is guage and analysis invited to share in these practices and of systemic oppres- support Volunteers in their work. sion. Staff and board members provide leadership of these efforts and use this lens in making deci- sions. -

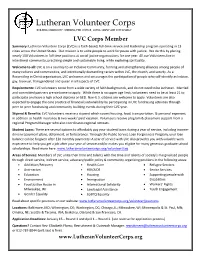

LVC Corps Member Summary: Lutheran Volunteer Corps (LVC) Is a Faith-Based, Full-Time Service and Leadership Program Operating in 13 Cities Across the United States

Lutheran Volunteer Corps BUILDING COMMUNITY, WORKING FOR JUSTICE, LIVING SIMPLY AND SUSTAINABLY LVC Corps Member Summary: Lutheran Volunteer Corps (LVC) is a faith-based, full-time service and leadership program operating in 13 cities across the United States. Our mission is to unite people to work for peace with justice. We do this by placing nearly 100 Volunteers in full-time positions at social justice organizations for one year. All our Volunteers live in intentional community, practicing simple and sustainable living, while exploring spirituality. Welcome to all: LVC is on a Journey to an Inclusive Community, forming and strengthening alliances among people of many cultures and communities, and intentionally dismantling racism within LVC, the church, and society. As a Reconciling in Christ organization, LVC welcomes and encourages the participation of people who self-identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered and queer in all aspects of LVC. Requirements: LVC volunteers come from a wide variety of faith backgrounds, and do not need to be Lutheran. Married and committed partners are welcome to apply. While there is no upper age limit, volunteers need to be at least 21 to participate and have a high school diploma or GED. Non-U.S. citizens are welcome to apply. Volunteers are also expected to engage the core practice of financial sustainability by participating in LVC fundraising activities through peer-to-peer fundraising and community-building events during their LVC year. Stipend & Benefits: LVC Volunteers receive a stipend which covers housing, food, transportation, & personal expenses, in addition to health insurance & two weeks’ paid vacation. Volunteers receive program & placement support from a regional Program Manager who also coordinates regional retreats. -

Lutheran Immersion and Formation (LIFE

LIFE in Service Network #LIFEinService The LIFE (Lutheran Immersion & Formation Experiences) in Service Network includes Border Servant Corps, Lutheran Volunteer Corps, Urban Servant Corps, and Young Adults in Global Mission. All LIFE in Service organizations are ministries of the ELCA or are ELCA affiliated. Leaders from each organization work together to provide opportunities for people in the ELCA to live, learn, and serve in their setting. Based in accompaniment, intentional community, simplicity, spirituality, and sustainability, each program is committed to being ecumenical, interfaith, LGBTQ- affirming, and social and racial justice-centered. Each year, more than 200 LIFE in Service volunteers serve within the United States and around the world. LIFE in Service organizations have more than 3,400 alumni who continue to live out the value of service in their lives. The ELCA Young Adults website (www.elca.org/youngadults) has links to each program, under "Ministries." Border Servant Corps (BSC) Young Adults in Global Mission (YAGM) Application Deadlines: January 15th Application Deadline: February 15th & March 25th Website: www.elca.org/YAGM Website: www.borderservantcorps.org Contact: Joseph Young; Contact: Kari Lenander; (575) 522-7119 Ext. 16; (800) 638-3522 Ext. 2446; [email protected] [email protected] Site(s) in: El Paso, TX; Las Cruces, NM Site(s) in: Argentina/Uruguay; Australia; Cambodia; Service Type: Year-long & short-term positions for Central Europe; Jerusalem/West Bank; Madagascar; adults 18+; border immersion experiences Mexico; Rwanda; Senegal; Southern Africa; United Program Year: August-July Kingdom Service Type: Year-long positions for adults 21-29 Lutheran Volunteer Corps (LVC) Program Year: August-July Application Deadlines: January 15th & April 1st Answers to Common Questions: Website: Yes! It’s okay to apply to more than one program to www.lutheranvolunteercorps.org discern which may be the best fit.