The Unspoken Epidemic of Violence in Indigenous Communities Helen Hughes Talk for Emerging Thinkers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Empowering Indigenous Australia Jacinta Nampijinpa Price 39

3 ContributorThe . A journal of articles published by the Policy Committee of the Liberal Party of Australia (WA Division) Keith Windschuttle | Daisy Cousens | Alex Ryvchin | Tony Abbott | Philip Ruddock Martin Drum | Aiden Depiazzi | Ross Cameron | Lyle Shelton | Robyn Nolan | Nick Cater Eric Abetz | Jacinta Nampijinpa Price | Rajat Ganguly | Caleb Bond | Neil James | Alexey Muraviev ContributorThe . Third edition, September 2017. Copyright © Liberal Party of Australia (WA Division). All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Policy Committee: Chairman Sherry Sufi, Jeremy Buxton, Alan Eggleston, Christopher Dowson, Joanna Collins, Murray Nixon, Dean Wicken, Christopher Tan, Daniel White, Claire McArdle, Jeremy Quinn, Steve Thomas MLC, Zak Kirkup MLA, Peter Katsambanis MLA and Ian Goodenough MP. The intention of this document is to stimulate public policy debate by providing individuals an avenue to express their views on topics they may have an interest or expertise in. Opinions expressed in these articles are those of their respective authors alone. In no way should the presence of an article in this publication be interpreted as an endorsement of the views it expresses either by the Liberal Party or any of its constituent bodies. Authorised by S. Calabrese, 2/12 Parliament Place, West Perth WA 6005. Printed by Worldwide Online Printing, 112-114 Mallard Way, Cannington WA 6107. If Liberalism stands for anything … it’s for the passion to contribute to the nation, to“ be free, but to be contributors, to submit to the discipline of the mind instead of the ordinary, dull discipline of a regimented mass of people. -

To Nuclear Waste

= FREE April 2016 VOLUME 6. NUMBER 1. TENANTSPG. ## HIT THE ROOF ABOUT REMOTE HOUSING FAILURE BIG ELECTION YEAR 2016 “NO” TO NUKE DUMP CRICKETERS SHINE P. 5 PG. # P. 6 PG. # P. 30 ISSN 1839-5279ISSN NEWS EDITORIAL Land Rights News Central Australia is published by the Central Land Council three Pressure rises as remote tenants take government to court times a year. AS A SECOND central The Central Land Council Australian community has 27 Stuart Hwy launched legal action against the Northern Territory Alice Springs government and an Alice NT 0870 Springs town camp is following tel: 89516211 suit, the Giles government is under increasing pressure to www.clc.org.au change how it manages remote email [email protected] community and town camp Contributions are welcome houses. Almost a third of Papunya households lodged claims for compensation through SUBSCRIPTIONS the Northern Territory Civil Land Rights News Central Administrative Tribunal in Australia subscriptions are March, over long delays in $20 per year. emergency repairs. A week later, half of the LRNCA is distributed free Larapinta Valley Town Camp Santa Teresa tenant Annie Young says the state of houses in her community has never been worse. to Aboriginal organisations tenants notified the housing and communities in Central department of 160 overdue water all over the front yard, sort told ABC Alice Springs. “Compensation is an Australia repairs, following a survey of like a swamp area,” Katie told “There’s some sort of inertia entitlement under the To subscribe email: by the Central Australian ABC. Some had wires exposed, or blockage in the system that [Residential Tenancies] Act,” [email protected] Aboriginal Legal Aid Service air conditioners not working, when tenants report things he told ABC Alice Springs. -

1 Family Violence in Aboriginal Australian Communities: Causes

1 Family Violence in Aboriginal Australian Communities: Causes and Potential Solutions Political Science Thesis April 25th 2014 Eden Littrell ‘14 I would like to express my gratitude to Carolyn Whyte, Director of Criminal Research and the Statistics Unit in the Northern Territory, and Kevin Schnepel, Lecturer at the University of Sydney, for a couple very informative email conversations. I would also like to thank Professor William Joseph for his advice and my father, Charles Littrell, for proof reading and emotional support. Last, but not least, thank you to my thesis advisor, Professor Lois Wasserspring, for her advice, support and constant feedback throughout this past year. 2 Prologue This thesis is an investigation into why family violence in Aboriginal Australian communities is so severe, and an examination of ways in which this violence might be decreased. I engage with the two competing narratives around violence in Aboriginal communities. The political left typically tells a story about the legacy of violent colonization, and the consequent need to improve Aboriginal legal rights. On the political right the narrative is less well defined, but the argument typically focuses on the importance of personal responsibility, or on the role of traditional culture in creating violence. I argue that competition between these narratives is harmful for actually reducing family violence, and that we should pursue evidence-based policy, such as alcohol restrictions, in addition to trialing and evaluating new policies. In Chapter 1, I briefly outline the higher rates of family violence in Indigenous communities. I also summarize the history of Aboriginal Australians and the contemporary argument around Aboriginal Australians and violence. -

Indigenous Languages in Parliamentary Debate, Legislation and Statutory Interpretation

1006 UNSW Law Journal Volume 43(3) LEGISLATING IN LANGUAGE: INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES IN PARLIAMENTARY DEBATE, LEGISLATION AND STATUTORY INTERPRETATION JULIAN R MURPHY* There are signs that Australia is beginning a long-overdue process of incorporating Indigenous languages into its parliamentary debates and legislation. These are significant developments in Australian public law which, to date, have attracted insufficient scholarly attention. This article begins the process of teasing out the doctrinal implications of this phenomenon. The article is in four Parts, the first two of which describe and normatively defend the trend towards Indigenous language lawmaking in Australia. The third Part looks abroad to how other countries facilitate multilingual parliamentary debate and legislation. Finally, the article examines the interpretative questions that multilingual legislation poses for Australian courts. Potential answers to these questions are identified within existing Australian and comparative jurisprudence. However, the ultimate aim of this article is not to make prescriptions but to stimulate further discussion about multilingual legislation, which discussion ought to foreground Indigenous voices. I INTRODUCTION Ngayulu kuwari kutju wangkanyi ngura nyangangka, munuṉa nguḻu nguwanpa ngaṟanyi. Ngayulu alatji watjaṉu aṉangu tjuṯa electionangka: ngayulu mukuringanyi tjukurpa katintjakitja aṉangu nguṟu kamanta kutu, kamanta nguṟu aṉangu kutu; ngayulu mukuringanyi nguṟurpa nguwanpa ngarantjakitja.1 In 1981, Neil Bell, newly elected member -

Northern Gas Pipeline Project ECONOMIC and SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Pty Ltd Northern Gas Pipeline Supplement to the Draft Environmental Impact Statement APPENDIX D ECONOMIC & SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Public NOVEMBER 2016 This page has been intentionally left blank Supplement to the Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Public— November 2016 © Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Pty Ltd Northern Gas Pipeline Project ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PUBLIC Circle Advisory Pty Ltd PO Box 5428, Albany WA 6332 ACN 161 267 250 ABN 36 161 267 250 T: +61 (0) 419 835 704 F: +61 (0) 9891 6102 E: [email protected] www.circleadvisory.com.au DOCUMENT CONTROL RECORD Document Number NGP_PL002 Project Manager James Kernaghan Author(s) Jane Munday, James Kernaghan, Martin Edwards, Fadzai Matambanadzo, Ben Garwood. Approved by Russell Brooks Approval date 8 November 2016 DOCUMENT HISTORY Version Issue Brief Description Reviewer Approver Date A 12/9/16 Report preparation by authors J Kernaghan B 6/10/16 Authors revision after first review J Kernaghan C 7/11/16 Draft sent to client for review J Kernaghan R Brooks (Jemena) 0 8/11/16 Issued M Rullo R Brooks (Jemena (Jemena) Recipients are responsible for eliminating all superseded documents in their possession. Circle Advisory Pty Ltd. ACN 161 267 250 | ABN 36 161 267 250 Address: PO Box 5428, Albany Western Australia 6332 Telephone: +61 (0) 419 835 704 Facsimile: +61 8 9891 6102 Email: [email protected] Web: www.circleadvisory.com.au Circle Advisory Pty Ltd – NGP ESIA Report 1 Preface The authors would like to acknowledge the support of a wide range of people and organisations who contributed as they could to the overall effort in assessing the potential social and economic impacts of the Northern Gas Pipeline. -

Aboriginal People, Bush Foods Knowledge and Products from Central Australia: Ethical Guidelines for Commercial Bush Food Research, Industry and Enterprises

Report 71 2011 Aboriginal people, bush foods knowledge and products from central Australia: Ethical guidelines for commercial bush food research, industry and enterprises Merne Altyerre-ipenhe (Food from the Creation time) Reference Group Josie Douglas Fiona Walsh Aboriginal people, bush foods knowledge and products from central Australia: Ethical guidelines for commercial bush food research, industry and enterprises Merne Altyerre-ipenhe (Food from the Creation time) Reference Group Josie Douglas Fiona Walsh 2011 Contributing author information Merne Altyerre-ipenhe (Food from the Creation time) Reference Group: V Dobson, MK Turner, L Wilson, R Brown, M Ah Chee, B Price, G Smith, M Meredith JC Douglas: CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, PO Box 2111, Alice Springs, Northern Territory, 0871, Australia. Previously, Charles Darwin University, Alice Springs. [email protected] FJ Walsh: CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, PO Box 2111, Alice Springs, Northern Territory, 0871, Australia. [email protected]. Desert Knowledge CRC Report Number 71 Information contained in this publication may be copied or reproduced for study, research, information or educational purposes, subject to inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source. ISBN: 978 1 74158 200 8 (Online copy) ISSN: 1832 6684 Citation Merne Altyerre-ipenhe (Food from the Creation time) Reference Group, Douglas J and Walsh F. 2011. Aboriginal people, bush foods knowledge and products from central Australia: Ethical guidelines for commercial bush food research, industry and enterprises. DKCRC Report 71. Ninti One Limited, Alice Springs. This report is one output of DKCRC Core Project ‘Sustainable bush products from desert Australia’. The Merne Altyerre-ipenhe Reference Group was funded through DKCRC, and its members also gave in-kind support to the research team, Douglas and Walsh. -

Wellington Shire Council, Being at Corner Foster and York Streets, Sale and Corner Blackburn and Mcmillan Streets, Stratford; 2

Resolutions In Brief Virtual Council Meeting via Skype To be read in conjunction with the Council Meeting Agenda 16 June 2020 COUNCILLORS PRESENT Alan Hall (Mayor) Gayle Maher (Deputy Mayor) Ian Bye Carolyn Crossley Malcolm Hole Darren McCubbin Carmel Ripper Scott Rossetti Garry Stephens APOLOGIES NIL ORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL – 16 JUNE 2020 RESOLUTIONS IN BRIEF ITEM PAGE NUMBER A PROCEDURAL A1 STATEMENT OF ACKNOWLEDGEMENT AND PRAYER A2 APOLOGIES NIL A3 DECLARATION OF CONFLICT/S OF INTEREST NIL A4 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES OF PREVIOUS COUNCIL MEETING A5 BUSINESS ARISING FROM PREVIOUS MEETING/S NIL A6 ACCEPTANCE OF LATE ITEMS NIL A7 NOTICES OF MOTION ITEM A7 (1) MCMILLAN CAIRNS - COUNCILLOR CROSSLEY A8 RECEIVING OF PETITIONS OR JOINT LETTERS ITEM A8(1) OUTSTANDING PETITIONS ITEM A8(2) RESPONSE TO PETITION - VEGETATION MANAGEMENT IN WELLINGTON SHIRE A9 INVITED ADDRESSES, PRESENTATIONS OR ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS NIL A10 QUESTIONS ON NOTICE NIL A11 MAYOR AND COUNCILLOR ACTIVITY REPORT ITEM A11(1) MAYOR AND COUNCILLOR ACTIVITY REPORT A12 YOUTH COUNCIL REPORT ITEM A12(1) YOUTH COUNCIL REPORT B REPORT OF DELEGATES - NIL C OFFICERS’ REPORT C1 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER ITEM C1.1 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S REPORT ITEM C1.2 MAY 2020 COUNCIL PERFORMANCE REPORT Resolutions In Brief 16 June 2020 2 ITEM PAGE NUMBER C2 GENERAL MANAGER CORPORATE SERVICES ITEM C2.1 ASSEMBLY OF COUNCILLORS ITEM C2.2 AUDIT & RISK COMMITTEE MINUTES ITEM C2.3 ADOPTION OF 20/21 BUDGET AND FEES AND CHARGES, STRATEGIC RESOURCE PLAN AND RATES AND SERVICE CHARGES ITEM C2.4 AMENDMENT OF COUNCIL -

Corporate and Community Development Agenda March 2021

AGENDA Corporate and Community Development Committee Meeting To be held on Tuesday 16 March 2021 at 4:00pm City of Rockingham Council Chambers Corporate and Community Development Committee Agenda Tuesday 16 March 2021 PAGE 2 Notice of Meeting Dear Committee members The next Corporate and Community Development Committee Meeting of the City of Rockingham will be held on Tuesday 16 March 2021 in the Council Chambers, City of Rockingham Administration Centre, Civic Boulevard, Rockingham. The meeting will commence at 4:00pm. MICHAEL PARKER CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 11 March 2021 DISCLAIMER PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER BEFORE PROCEEDING: Statements or decisions made at this meeting should not be relied or acted on by an applicant or any other person until they have received written notification from the City. Notice of all approvals, including planning and building approvals, will be given to applicants in writing. The City of Rockingham expressly disclaims liability for any loss or damages suffered by a person who relies or acts on statements or decisions made at a Council or Committee meeting before receiving written notification from the City. Corporate and Community Development Committee Agenda Tuesday 16 March 2021 PAGE 3 City of Rockingham Corporate and Community Development Committee Agenda 4:00pm Tuesday 16 March 2021 1. Declaration of Opening Acknowledgement of Country This meeting acknowledges the traditional owners and custodians of the land on which we meet today, the Nyoongar people, and pays respect to their elders -

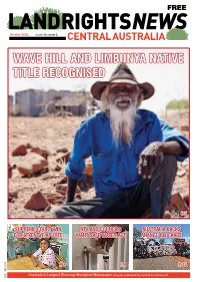

Wave Hill and Limbunya Native Title Recognised

FREE October 2020 VOLUME 10. NUMBER 3. WAVE HILL AND LIMBUNYA NATIVE TITLE RECOGNISED P. 5 SUPREME COURT WIN NT LAND COUNCILS AUSTRALIA BACKS FOR LTYENTYE APURTE WANT SAFE WATER ACT ANANGU BLOCKADE P. 3 P. 8 P. 15 ISSN 1839-5279ISSN NEWS EDITORIAL Land councils call for community housing model Land Rights News Central Australia is published by the THE NORTHERN Terri- Central Land Council three tory’s land councils want times a year. the Morrison and Gunner governments to replace the The Central Land Council NT’s failed public housing 27 Stuart Hwy system with a new Aboriginal- Alice Springs controlled model for remote NT 0870 communities, homelands and town camps. tel: 89516211 Meeting in Darwin with www.clc.org.au Indigenous Australians email [email protected] Minister Ken Wyatt and NT Chief Minister Michael Contributions are welcome Gunner before the Territory election, the land councils demanded a return of responsibility for housing SUBSCRIPTIONS design, construction, Land Rights News Central maintenance and tenancy Australia subscriptions are management to Aboriginal $22 per year. people. The land councils agree that It is distributed free of this is essential to closing charge to Aboriginal the yawning gap between organisations and Aboriginal Territorians and communities in Central The chairs of the four NT land councils tell ABC TV News about their community-controlled housing model. the rest of the country. Australia. They support a careful keep negotiating with both We now have a roadmap for and NT governments to see it To subscribe email transition to a community governments about the model. -

Annual REPORT

Annual REPORT 2017-2018 402 7.6 Aboriginal and Tonnes less sugar Torres Strait consumed through Islander jobs sugary drinks in communities Outback Stores 85% Committed to Of all team 430 Closing the Gap members employed Tonnes of fresh fruit in stores are and vegetables sold Aboriginal and Torres Strait in communities Islander 2 OUTBACK STORES ANNUAL REPORT 17-18 3 Vision Outback Stores aspires to be the national company of choice by being the most efficient and effective provider of retail services and deliver quality and sustainable retail stores. Mission To make a positive difference in the health, employment and economy of remote Indigenous communities, by providing quality, sustainable retail stores. Nutritional Aim To improve the health of Indigenous people living in remote communities by improving access to a nutritious and affordable food supply. 4 OUTBACK STORES ANNUAL REPORT 17-18 5 Table of contents Letter of Transmittal 9 Chairman’s Report 10 CEO’s Report 12 Health and Nutrition 14 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Employment and Training 22 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Team Members Shine 24 Steve Bradley: A Decade as Chairman 30 Because of Her, We Can! 34 Santa Teresa Excellence Recognised 42 Bakeries Provide Jobs and Freshness 46 Work Health and Safety 48 Store Locations 50 Organisation Structure 52 Outback Stores’ Performance 55 Corporate Governance 57 Other Information 62 Index of Annual Report Requirements 65 Directors Report 69 Directors Declaration 76 Auditors Independence Declaration 77 Independent Auditors -

2017/01: Should Australia Change the Date of Australia Day? File:///C:/Dpfinal/Schools/Doca2017/2017Ozday/2017Ozday.Html

2017/01: Should Australia change the date of Australia Day? file:///C:/dpfinal/schools/doca2017/2017ozday/2017ozday.html 2017/01: Should Australia change the date of Australia Day? What they said... 'We can't reasonably expect indigenous Australians to "draw that line in history" [between past wrongs and present reality] while we continue to celebrate on a day which marks the beginning of their dispossession and the loss of their cultural control of this land' Former federal Resources and Science Minister, Ian Macfarlane 'The shire needs to retract what it's doing. It's not in line with community attitudes. I strongly condemn them for this whole thing. They've really upset a lot of people and are not representing the ratepayers. Australia Day is Australia Day' Indigenous spokesperson, Robert Isaacs, criticising Freemantle's attempt to shift the date of Australia Day The issue at a glance On August 25, 2016, the Freemantle Council announced that the Western Australian city would no longer hold its Australia Day celebrations on January 26th. The change was made out of respect for the feelings of Indigenous Australians, many of whom do not find the date a reason for celebration as it coincides with the initial dispossession of their ancestors. The Council subsequently announced that it would instead celebrate on January 28th with an event called 'One Day in Fremantle'. Citizenship ceremonies were also intended to be held on January 28th rather than the usual January 26th. On December 5, 2016, the federal Government intervened and required Freemantle to hold its citizenship ceremonies on January 26th. -

Der Herausgeber AUSTRALIENS AUSWÄRTIGE KULTURPOLITIK

1 Der Herausgeber Nummer 15, die erste Nummer in meiner Verantwortung, wurde erfreulicherweise so aufgenommen, dass ich mit dem neuen Format fortfahre. Das Schwerpunktthema Multikulturalismus hat trotz einiger Lücken, die die Leser unschwer feststellen werden, eine breite Palette an Beiträgen stimuliert, wobei es erfreulich ist, dass das Thema Aborigines breiten Raum einnimmt. Die Bereiche Rezension und Dokumentation haben sich bewährt und erweitert, so dass die Leser mehr Information finden werden. Hinsichtlich der Recherchehilfen im Internet werden AusLit und andere erwähnt. Hier sollten sich vor allem jüngere Mitglieder aufgerufen fühlen, auch wenn bei der Altersgruppe, zu der der Herausgeber gehört, die höchsten Zuwachsraten in der Internetnutzung festgestellt wurden. Noch etwas problematisch ist die formale Seite des Newsletter, und das style sheet sei den Beiträgern besonders empfohlen. Wie erwähnt, werden die Leser einige Lücken beim Thema Multikulturalismus konstatieren. Das Thema ist abgesunken, der in Forschung, Lehre und populärer Literatur weit verbreitete Begriff ist ins "Aus" geraten, was auch die 2. Auflage der Enzyklopädie The Australian people (hsg. von J. Jupp, 2002) beweist. Doch ist es schon signifikant, wenn der australische Premierminister John Howard anlässlich einer Ansprache in Berlin am 2. Juni 2002 dieses Wort nicht ein einziges Mal in den Mund nahm, ja auch das Wort Kultur vermied und keinen Hinweis auf Aborigines machte. Hätte sein Vorgänger auch darauf verzichtet, auf Multikulturalität als Folge kultureller oder demographischer Gegebenheiten hinzuweisen? Als er 1995 Berlin besuchte, tat er es jedenfalls nicht. Für Howard waren Wirtschaft, Finanzpolitk, ethical capitalism, wie er ihn nannte, Schlüsselworte, die in einem Forum der Deutschen Bank sicher interessant waren, aber nicht das letzte Wort sein können.