Drought, Flood, Saving, and Sharing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amtrak Multiple Passenger Train Routes Crossing Montana: Are They Needed? Angelo Rosario Zigrino the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Graduate School Professional Papers 1972 Amtrak multiple passenger train routes crossing Montana: Are they needed? Angelo Rosario Zigrino The University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Recommended Citation Zigrino, Angelo Rosario, "Amtrak multiple passenger train routes crossing Montana: Are they needed?" (1972). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 7979. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/7979 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMTRAK MULTIPLE PASSENGER TRAIN ROUTES CROSSING MONTANA* ARE THEY NEEDED? By Angelo R. Zigrino B.S., University of Tennessee, I9 6 I Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Business Administration UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1972 proved\byi 3 Chair: Board of Examiners Da Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: EP38780 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI PMsIishing UMI EP38780 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

The Sentinel Butte Lignite Field, North Dakota and Montana

THE SENTINEL BUTTE LIGNITE FIELD, NORTH DAKOTA AND MONTANA. By A. G. LEONARD and CARL D. SMITH. INTRODUCTION. As shown by the key map (fig. 1), the Sentinel Butte field is a small area near the center of the Fort Union region of coal and lignite bear ing rocks of Tertiary age, which cover a considerable area in the north ern part of Wyoming, the eastern quarter of Montana, the western FIG. 1. Index map showing location of the Sentinel Butte lignite field, North Dakota and Montana. half of North Dakota, arid the northwest corner of South Dakota. The field examined in 1907 comprises approximately 25 townships 19 in Billings County, N. Dak., and 6 in Dawson County, Mont., on either side of the Northern Pacific Railway.J 15 16 CONTRIBUTIONS TO ECONOMIC GEOLOGY, 1907, PART II. The geologic investigations were undertaken primarily for the pur pose of classifying the public lands with special regard to lignite. In order to do this, the character, depth, and horizontal distribution of the beds of lignite were studied in detail, and outcrops and exposures were located with reference to established land corners. This region has been investigated in a general way by a number of geologists, notably by Wood, Wilder, and Leonard, of the North Dakota Geological Survey, and by Storrs, of the Federal Survey. In the field work the writers were ably assisted by Fred H. Kay and W. H. Clark, and in the office Mr. Kay compiled the accompanying map from the original township plats used in the field. ACCESSIBILITY. Much of the lignite of this field is accessible without great difficulty. -

LEWISTOWN NEWSPAPER INDEX Dale Jones 2020

Index of Newspaper Articles Related to Railroads and Transportation in Central Montana from microfilm located at the Lewistown, Montana Public Library List of the newspapers in this index: Fergus County Argus [Lewistown] Fergus County Democrat [Lewistown] Fergus County News [Lewistown] Judith Basin Star [Hobson] Judith Gap Journal [Judith Gap] Lewistown Daily News [Lewistown]Lewistown Democratic News [Lewistown] Lewistown News Argus [Lewistown] The Stanford World [Stanford] Compiled by Dale Jones - July 2005 Copyright Dale Jones 2020 www.railroads-of-montana.com LEWISTOWN NEWSPAPER INDEX Dale Jones 2020 www.railroads-of-montana.com In the late 1980s when I lived in Lewistown, I went through the Lewistown library's entire microfilm collection of Lewistown area newspapers and photocopied the information, this is an index of the articles I have collected. It must be noted that this is in no way meant to be a comprehensive index, only what I found interesting for a future book. The titles are just the general scope of the article. You will have to visit the Lewistown Library to locate and copy the actual microfilm copies. Since the information is on microfilm, some of the copies are not the best since the originals were not the best, generally everything is legible, but then some of the articles are challenging to read. Whatever the case, there is some fantastic information for anyone interested in Central Montana transportation history. Just looking at the index is fascinating - take a look! I have organized the index with related articles under these general headings; BA&P - CB&Q - General Great Northern Railway GN & Milwaukee Road [there may be info from both RR's] Montana RR & Others [this is the actual "Montana Railroad" - the "Jawbone!"] BA&P - CB&Q - General BA&P-December-24-1912-BA&P Will Electrify Montana Road-Misc. -

` Northern Pacific Railway and Burlington Northern

` NORTHERN PACIFIC RAILWAY AND BURLINGTON NORTHERN RAILROAD COLLECTION FINDING AID YELLOWSTONE GATEWAY MUSEUM OF PARK COUNTY LIVINGSTON, MONTANA 2018 0 NORTHERN PACIFIC RAILWAY AND BURLINGTON NORTHERN RAILROAD COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Historical Note……………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Scope and Content Note…………………………………………………………………….……. 8 Series Description………………………………………………………………………………….9 Series 1 Employees/Payroll………………………………………………………………………13 Series 2 Engineering Department……………………………………………………………….20 Series 3 Financial/Accounting Department…………………………………………………….21 Series 4 Maintenance of Way Department…………………………………………………......44 Series 5 Mechanical Department………………………………………………………………..45 Series 6 Operations Department…………………………………………………………….......45 Subseries Office of Trainmaster……………………………………..………………………….57 Series 7 Personnel Department…………………………………………………………….……62 Series 8 Marketing/Public Relations Department………………………………………..…….85 Series 9 Unions and Organizations………………………………………………………..…….91 Series 10 Burlington Northern Department………………………………………………..…..92 Series 11 Train Shows, Railroad Clubs, and Commemorative Events……….………………99 Series 12 Oversize Calendars, Maps, Plans, and Documents…………………….……….….101 Series 13 Oversize Ledgers………………………………………………………….…….……112 Series 14 Objects……………………………………………………………………..….……....119 Series 15 Photographs………………………………………………………………...………...132 1 NORTHERN PACIFIC RAILWAY AND BURLINGTON NORTHERN RAILROAD COLLECTION PROVENANCE: Warren McGee donated the -

Lombard Cemetery Lombard Broadwater County, Montana August 2011

LOMBARD CEMETERY LOMBARD BROADWATER COUNTY, MONTANA AUGUST 2011 “Lombard was a railroad town in its early days. The station was at the crossroads of the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee. For many years there was no automobile road into town and all citizens had to go and come by train. The name was chosen to honor A. G. Lombard, chief engineer of the Montana Railroad during its construction. The original name was Castle Junction. In 1900 the community was dominated by the “Jaw Bone” Railroad. *Billy Kee (Kie), the Chinese major, hotel proprietor, and man-about-town was famous for this two-story High Point Inn, which he opened in 1897, serving good meals and featuring a bathroom with hot and cold running water. Kee ran his hotel with flexibility: when he went to bed he left a light burning and the register open; late-comers simply scrawled their names in the book, chose a key, and raced the bedbugs to the rooms (Stearns). The post office operated 1896- 1957; George Walker was the postmaster.” Roberta Carkeek Cheney, Names on the Face of Montana, The Story of Montana’s Place Names, Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, 1983. “Lombard, walled in by rock cliffs, was inaccessible except by railroad or horseback until the first road was constructed about 1930. Ironically, the town paid road taxes from the time of it founding [ca. 1897] but depended mostly on two transcontinental railways for its commerce. The town was named for A.G. Lombard, civil engineer for the Northern Pacific.” Broadwater Bygones “Across Sixteen Mile Creek are two stones, and they are all that remain visible of the old grave yard. -

The Chinese As Railroad Workers After Promontory”

Web exclusive essay published at chineserailroadworkers.stanford.edu © 2019 Stanford University Chinese Railroad Workers of North America Project Bibliographic Essay for “The Chinese as Railroad Workers after Promontory” SHELLEY FISHER FISHKIN Stanford University Due to space limitations, many of the end notes in “The Chinese as Railroad Workers after Promontory” by Shelley Fisher Fishkin in The Chinese and the Iron Road: Building the Transcontinental, edited by Gordon H. Chang and Shelley Fisher Fishkin (Stanford University Press, 2019), had to be significantly truncated. This bibliographic essay supplements the references cited in the print essay. It also adds some material that had to be cut due to space constraints. After briefly summarizing “The Chinese as Railroad Workers after Promontory,” it extends and complements—but does not replicate—the citations in the print essay. (This bibliographic essay does not represent a complete inventory of sources used.) The number of the end note in the book that is being amplified here follows at the end of each paragraph or section in square brackets. [Note: A version of “The Chinese as Railroad Workers after Promontory” that is twice as long as the one in The Chinese and the Iron Road and that integrates much of the information in this bibliographic essay was published in Chinese in 北美鐵路華工:歷史、 文學與視覺再現 [Chinese railroad workers in North America: Recovery and representation], edited by Hsinya Huang [黃心雅] (Taipei: Bookman [台北:書林出版社], 2017). See Shelley Fisher Fishkin, 從天使城到長島:美洲橫貫鐵路竣工後在美國的鐵路華 1 Web exclusive essay published at chineserailroadworkers.stanford.edu © 2019 Stanford University Chinese Railroad Workers of North America Project 工 [From Los Angeles to Long Island: Chinese railroad workers in America after the transcontinental], in the volume edited by Hsinya Huang noted above, pp. -

Valuation Section Montana 2

31 VALUATION SECTION MONTANA 2. GENERAL LOCATION: Va.luat:i on Section Montana 2 covers about 9lm11es of the Chioago Milwaukee and st. Paul Railway Company's Puget Sound Extension in Montan.a, lying between. a point a.bout 3-3/10 miles wast of' Ha.rlo",'1ton, Montana and Lombard. The line follows the Musselshell Rive~ to its headwaters, orosses the Little Belt Mountain Di ',Tide and desoends to the Missouri Hiver at Lombard, pa.ssing th:rpugh Me s.gn.er ) Gallatin and Broadwa.ter Counties. The original line was oonstruoted by the Montana. Rail road Company in two seotions; that from the point near Harlowton to Summit being built in 1900 and the part between Summit and Lom bard in the yeaza lS94-95-96-97. The Montana. Railroad Company entered into an agreement and lease with the Chioago Milwaukee and Puget Sound Railway Company on December 11th, 1907, in which 'the former Company agreed to improve the line between Harlowton a.nd Lombard and gra.ntect tl'aokage rights to the la.tter Oompany for a period of 99 years. On January 15th, 1910 the Montana Railroad Company deeded its entire road and property lying between Lewis town and Lombard, Montana to the Chioago Milwaukee and Puget Sound RaJ.lwa.y Compa.ny. £VRVE~S: 'rna reconnoissanoe in September 1904 beginning at Miles City and extendir~ west along Yellowstone and Musselshell Rivers to Harlowton, as described under Valuation Seotion Montana No.1, was oontinued on west to Lombard along the Montana Railroad and from this ,report it was deoided to use the Montana Railroad for train operation on this Section. -

History of the Upper Musselshell Valley to 1920

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1966 History of the upper Musselshell Valley to 1920 Harold Joseph Stearns The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Stearns, Harold Joseph, "History of the upper Musselshell Valley to 1920" (1966). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2575. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2575 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HISTORY OF THE UPPER MUSSELSHELL VALLEY TO 1920 By Harold Joseph Stearns B. A. University of Notre Dame, 1962 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1966 Approved by : Chairman, Board of Examiners / v t- X —-■> Deai!i, Graduate School / M A R 1 e 1966 Date UMI Number; EP35017 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Oissartatlon Publishing UMI EP35017 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). -

Montana State Rail Plan Update (2000)

20002000 MontanaMontana StateState RailRail PlanPlan UpdateUpdate AA reportreport toto MontanaMontana DepartmentDepartment ofof TransportationTransportation SubmittedSubmitted byby R.L.R.L. BanksBanks && Associates,Associates, Inc.Inc. Washington,Washington, DCDC andand TiburonTiburon,, CACA InIn AssociationAssociation withwith HardingHarding ESEESE Helena,Helena, MTMT 2000 Montana State Rail Plan Update A Report To Montana Department of Transportation Table of Contents Page INTRODUCTION 1 STATE RAIL PLANNING 2 Federal Requirements 2 Montana's Current Rail Planning 2 History of Rail Planning in Montana 3 Public Service Commission 6 MONTANA'S RAILROADS 7 Description of Montana's Rail Network 7 Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway Company 9 Union Pacific Railroad Company 22 Montana Rail Link 23 Dakota, Missouri Valley and Western Railroad, Inc. 29 Central Montana Rail, Inc. 30 Montana Western Railway 31 Rarus Railway Company 33 Tongue River Railroad Company 35 Procedures for Analysis of Freight Lines 37 Rail Freight Traffic Flows 41 Relation of Montana's Rail Network to Regional and National Networks 51 Relative Importance of Montana Railroads in Moving Freight and Passengers, Compared with other Modes 54 Historical Growth and Changes in Montana's Rail Network 57 Railroad-Related Facilities 60 RAIL LINES AT RISK 62 RAIL PASSENGER SERVICE 69 Existing Amtrak Route 69 Future of Amtrak 70 Rail Passenger Service Deficiencies, Opportunities to Expand 70 Economic Feasibility of Passenger Rail on Other Primary State Corridors 74 - i - 2000 Montana -

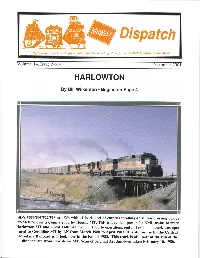

Wwfsi Dispatch

WWfSi Dispatch Dedicate Volume 14, Issue No. 4 December 2001 HARLOWTON By Bill Wllkerson - Begins on Page 4 SD's #556/505/522/513 are E/B with 41 loads and 12 empties totalling 4350 tons crossing bridge #NM-1026 over a County road by Hoosac MT. This was typical power for NML trains between Harlowton MT and Great Falls MT from c. 1973 to operations end in 1980. This track was oper• ated to Geraldine MT by BN from March 1980 to April 1983. It is still in use by the Central Montana Railroad who took over in the Fall of 1983. This track is also part of the run of the dinner train from Lewistown MT. Scan of original Art Jacobsen taken February 10,1980. Page 2 Upper - X553E is switching the U.S. Gypsum plant at Heath MT on 10/30/79. Prior to 4/77 this line ran east to Grassrange MT, and from 1917 to mid-1972, it went Winnett MT. BN continued this operation for five years after 3/80, when USG closed this mine and operation. Lower - Same train as on page one is at Geraldine MT. 1940 caboose #991891 is on the main while the power switches the elevator, which burned down April 2001. Scans of Art Jacobsen slides. Page 3 MilWest 2002 Annual Meet Dues Reminder Lewistown MT August 8-10,2002 The membership renewal slips for 2002 were included in the previous Dispatch. Many of you have already To be held at the Yogo Inn Best Western renewed and we thank you for that. -

Musselshell River Is the Valley's

THE UPPER MUSSELSHELL VALLEY: A GRASSROOTS AND BIOREGIONAL HISTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University Of Agriculture and Applied Science By Miles Dwight Lewis In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY Major Department: History January 2012 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title THE UPPER MUSSELSHELL VALLEY: A GRASSROOTS AND BIOREGIONAL HISTORY By Miles D. Lewis The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Thomas Isern Chair John Helgeland Mark Harvey Kimberly Porter Kevin Sedivec Approved: 30 January 2012 John Cox Date Department Chair ii ABSTRACT The Upper Musselshell Valley: A Grassroots and Bioregional History chronicles the history of central Montana’s Upper Musselshell Valley in an attempt to craft a viable history of region. As a corrective measure or alternate explanation that revises not only historical interpretation, but also takes into account who, or what group, is the driving force behind each distinct narrative stream (i.e. grand narrative history--histories penned by professional scholars and academics—or grassroots perspectives, the history of region as told by local dwellers), which stream is or is not authoritative, and how to modify, adjust, or meld the various interpretations in order to arrive at a more judicious, perceptive, and democratic version of history. The New Regional History is a coalescence of the grand narrative, the grassroots perspective, bioregionalism, and memory studies that is concerned with humankind’s interaction with the physical environment, and the succession of cultures within that environment. -

Table of Content

TABLE OF CONTENT Section 1 .........Project Overview ...............................................Section 1 Page 1 – 7 Introduction .......... .......................................................................................... 1 Project Purpose.... .......................................................................................... 1 Project Goals........ .......................................................................................... 5 TEA-21 Planning Factors................................................................................ 5 Public Involvement .......................................................................................... 7 Overview of Transportation Modeling System ................................................ 7 Section 2 .........Community Transportation System Guiding Principles ..........................................................................Section 2 Page 1 – 4 Community Transportation Guiding Principles................................................ 1 Section 3 .........Historic and Projected Growth...........................Section 3 Page 1 – 15 Land Use.............. .......................................................................................... 1 Historic Population & Employment Growth..................................................... 2 Typical 2000 Travel Patterns .......................................................................... 8 Projected 2002-2027 Population & Employment Growth ............................... 11 Section 4 .........Streets