A Case Study of Dhupguri Block, West Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Disaster Management Plan 2020-21 Jalpaiguri

District Disaster Management Plan 2020-21 Jalpaiguri District Disaster Management Authority Jalpaiguri O/o the District Magistrate, Jalpaiguri West Bengal Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Aim and Objectives of the District Disaster Management Plan............................................ 1 1.2 Authority for the DDMP: DM Act 2005 ............................................................................... 2 1.3 Evolution of the DDMP ........................................................................................................ 3 1.4 Stakeholders and their responsibility .................................................................................... 4 1.5 How to use DDMP Framework ............................................................................................. 5 1.6 Approval Mechanism of the Plan: Authority for implementation (State Level/ District Level orders) ............................................................................................................................... 5 1.7 Plan Review & Updation: Periodicity ................................................................................... 6 2 Hazard, Vulnerability, Capacity and Risk Assessment ............................................................... 7 2.1 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Assessment ......................................................................... 7 2.2 Matrix of Seasonality of Hazard .......................................................................................... -

W.B.C.S.(Exe.) Officers of West Bengal Cadre

W.B.C.S.(EXE.) OFFICERS OF WEST BENGAL CADRE Sl Name/Idcode Batch Present Posting Posting Address Mobile/Email No. 1 ARUN KUMAR 1985 COMPULSORY WAITING NABANNA ,SARAT CHATTERJEE 9432877230 SINGH PERSONNEL AND ROAD ,SHIBPUR, (CS1985028 ) ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS & HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 14-01-1962 E-GOVERNANCE DEPTT. 2 SUVENDU GHOSH 1990 ADDITIONAL DIRECTOR B 18/204, A-B CONNECTOR, +918902267252 (CS1990027 ) B.R.A.I.P.R.D. (TRAINING) KALYANI ,NADIA, WEST suvendughoshsiprd Dob- 21-06-1960 BENGAL 741251 ,PHONE:033 2582 @gmail.com 8161 3 NAMITA ROY 1990 JT. SECY & EX. OFFICIO NABANNA ,14TH FLOOR, 325, +919433746563 MALLICK DIRECTOR SARAT CHATTERJEE (CS1990036 ) INFORMATION & CULTURAL ROAD,HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 28-09-1961 AFFAIRS DEPTT. ,PHONE:2214- 5555,2214-3101 4 MD. ABDUL GANI 1991 SPECIAL SECRETARY MAYUKH BHAVAN, 4TH FLOOR, +919836041082 (CS1991051 ) SUNDARBAN AFFAIRS DEPTT. BIDHANNAGAR, mdabdulgani61@gm Dob- 08-02-1961 KOLKATA-700091 ,PHONE: ail.com 033-2337-3544 5 PARTHA SARATHI 1991 ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER COURT BUILDING, MATHER 9434212636 BANERJEE BURDWAN DIVISION DHAR, GHATAKPARA, (CS1991054 ) CHINSURAH TALUK, HOOGHLY, Dob- 12-01-1964 ,WEST BENGAL 712101 ,PHONE: 033 2680 2170 6 ABHIJIT 1991 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SHILPA BHAWAN,28,3, PODDAR 9874047447 MUKHOPADHYAY WBSIDC COURT, TIRETTI, KOLKATA, ontaranga.abhijit@g (CS1991058 ) WEST BENGAL 700012 mail.com Dob- 24-12-1963 7 SUJAY SARKAR 1991 DIRECTOR (HR) BIDYUT UNNAYAN BHAVAN 9434961715 (CS1991059 ) WBSEDCL ,3/C BLOCK -LA SECTOR III sujay_piyal@rediff Dob- 22-12-1968 ,SALT LAKE CITY KOL-98, PH- mail.com 23591917 8 LALITA 1991 SECRETARY KHADYA BHAWAN COMPLEX 9433273656 AGARWALA WEST BENGAL INFORMATION ,11A, MIRZA GHALIB ST. agarwalalalita@gma (CS1991060 ) COMMISSION JANBAZAR, TALTALA, il.com Dob- 10-10-1967 KOLKATA-700135 9 MD. -

North Circle - I

Government of West Bengal Public Works Department Establishment Branch Khadya Bhawan 11A,Mirza Ghalib Street,Kolkata -87. No.: 52-E/PWD-11041/2/2020-DIR (PWD) Dated:17.08.2020 NOTIFICATION The Restructuring of various offices under the preview of the Public Works Department has been undertakenvide Notification No.178 dated 20.12.2019. As a result thereof, necessity of re-jurisdiction of Divisions and Sub-Divisions under the Zones of PWD have been felt to cope with the requirement of proper implementation and execution of works relating to restructuring of various offices under Public Works Department. 2. Now, in view of above, the Governor is pleased, in the interest of public service to create re-jurisdiction of Divisionsand Sub-Divisionsunder the Zonesof PWDin the following manner: (AI Rejurisdiction of Divisionand Sub-Division Offices under administrative jurisdiction of North Zone Existing Name of office Name of office by Zonal Chief Jurishdlction of office by Zonal Chief (Division/Sub-Division) Engineer Engineer (Block / Municipality) NORTH CIRCLE - I Coochbehar Division Coochbehar Division-I Coochbehar Sub-Division-I Cooch Behar Sub-Division Eastern part of Dharala river of Cooch Behar-I block inclusive of Cooch Behar Municipality Coochbehar Sub-Dlvlsion-ll Tufanganj Sub-Division Tufanganj-I inclusive of Tufanganj municipality and Tufanganj-II block Dinhata Sub-Division Dinhata Sub-Division Dinhata-I inclusive of Dinhata erstwhile Jorai Costr. Sub- municipality and Dinhata-II block and Division. Sitai block Alipurduar Division Alipurduar Division Alipurduar Sub-Division. Alipurduar Sub-Division Block Alipurduar-I inclusive of Alipurduar Municipality and Eastern part of Kalchini Block consisting of Buxa and Jayanti Notification No: 52-E/PWD-ll041/2/2020-DIR (PWD) dated 17.08.2020 Rejurisdiction of Division and Sub-Division Offices under administrative jurisdiction of North Zone Existing Name of office Name of office by Zonal Chief lurishdiction of office by Zonal Chief (Division/Sub-Division) Engineer Engineer (Block / Municipality) Kamakhyaguri Constr. -

A Case Study of the Tea Plantation Industry in Himalayan and Sub - Himalayan Region of Bengal (1879 – 2000)

RISE AND FALL OF THE BENGALI ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF THE TEA PLANTATION INDUSTRY IN HIMALAYAN AND SUB - HIMALAYAN REGION OF BENGAL (1879 – 2000) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY BY SUPAM BISWAS GUIDE Dr. SHYAMAL CH. GUHA ROY CO – GUIDE PROFESSOR ANANDA GOPAL GHOSH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL 2015 JULY DECLARATION I declare that the thesis entitled RISE AND FALL OF THE BENGALI ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF THE TEA PLANTATION INDUSTRY IN HIMALAYAN AND SUB - HIMALAYAN REGION OF BENGAL (1879 – 2000) has been prepared by me under the guidance of DR. Shyamal Ch. Guha Roy, Retired Associate Professor, Dept. of History, Siliguri College, Dist – Darjeeling and co – guidance of Retired Professor Ananda Gopal Ghosh , Dept. of History, University of North Bengal. No part of this thesis has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. Supam Biswas Department of History North Bengal University, Raja Rammuhanpur, Dist. Darjeeling, West Bengal. Date: 18.06.2015 Abstract Title Rise and Fall of The Bengali Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of The Tea Plantation Industry In Himalayan and Sub Himalayan Region of Bengal (1879 – 2000) The ownership and control of the tea planting and manufacturing companies in the Himalayan and sub – Himalayan region of Bengal were enjoyed by two communities, to wit the Europeans and the Indians especially the Bengalis migrated from various part of undivided Eastern and Southern Bengal. In the true sense the Europeans were the harbinger in this field. Assam by far the foremost region in tea production was closely followed by Bengal whose tea producing areas included the hill areas and the plains of the Terai in Darjeeling district, the Dooars in Jalpaiguri district and Chittagong. -

Chapter 2 STUDY AREA

Chapter 2 STUDY AREA . STUDY AREA An important inclusion in the National Parks family, Gorumara National Park (GNP) is famous for its prestigious inhabitant one-horned great Indian Rhino. This is one of the last few small pockets in Eastern India harboring natural population of Rhinoceros unicornis L., along with other mega and majestic herbivores like Indian Elephant, Gaur or Indian Bison and is covered with rich vegetation. GNP had been a wild land sanctuary (Vide notification no. 5181-FOR, date: 02.08.1949) and a reserved forest since 1895 (notification no. 3147- FOR, date: 2nd July, 1895 with corrections later on), under the Indian forest act (VII of 1878). Formerly, an area of 2129 acre was first declared as Gorumara Wild Life Sanctuary (GWLS) vide Gov. Notification no. 5181-For, date: 02.08.1949. Subsequently, the notification under the Wildlife (protection) act, 1972, [vide no. 5400- For, date: 24th June, 1976] covering a total area of 8.62 sq km declaring the area as GWLS. In 1994, with Govt. notification no. 319_ For, dated 31st January, 1994 was issued with the intention of declaring the area as GNP, with major extension of the existing GWLS and now it covered a total area of 79.99 sq km. On 21st November, 1995, following a reorganization of the forest directorate of West Bengal, the total area of the GNP, curved out of the Jalpaiguri forest division was handed over to the Wild Life Division – II under the Conservator of Forest, Wild Life Circle [vide GOV. of West Bengal notification no. 4983- For, date 25th September, 1995]. -

Appendix I Tea Estates, Name of the Company and Year of Establishment

Appendix I Tea Estates, Name of the Company and Year of Establishment. Name of the Propritors, agents Year of Tea Garden or managing agent Establishment (P.S. Banarhat) Before 1954 After 1994 S.No. 1. Ambari Messers Davenport & Co. Ltd. Ambari Tea Co 1908 2. Banarhat Messers Andrew Yule & Co Ltd . Same 1875 3. Binnaguri Messers Macneill & Barry Ltd . Same 1898 4. Chamurchi The Chamurchi Tea Co. Ltd , Chamurchi Tea & 1892 Jalpaiguri Textile Institute 5. Chunabhatti Messers Andrew Yule & Co Ltd Same 1894 6. Debpara The Debpara Tea Co. Ltd ., Same 1898 Jalpaiguri 7. Diana The Diana Tea Co Ltd. Jalpaigu ri Same 1911 8. Gairkata MessersGillanders Arbuthnot Same 1890 & Co Ltd. 9. Gandrepara Messers Duncan Brothers & Co Ltd . Goodricke Group 1894 10. Haldibari Messers Davenport & Co. Ltd . Same 1888 11 . Kalabari The Eastern Tea Co Ltd . Same 1878 12. Karbala Messers Andrew Yule & Co Ltd Same 1895 13. Kathalguri The Kathalguri Tea Co. Ltd , Same 1895 Jalpaiguri 14. LakshiKanta The Lakshikanta Tea Co. Ltd . Rangamatee Tea Co. 1929 15. Lakshi para Messers Duncan Brothers & Co Ltd . Goodricke Group. 1897 16. Magulkata Messers Shaw Wallace & Co ltd. Bijay Nagar Tea Co. 1881 17. Maraghat Messers Macneill & Barry ltd. Maraghat Tea Co 1919 18. New Dooars Messers Andrew Yule & Co ltd. Same 1894 19. Pa lasbari The Palasbari tea Co. Ltd . Same 1896 20. Redbank The New Redbank Tea Co. ltd./ Same 1922 The North Bengal Planters Ltd. 21 . Rheabari Mesers Fazlur Rahaman & Others Kothari Plantation 1913 Industries 22 .Surendranagar The New Redbank Tea Co. ltd Surendranagar Tea Co 1939-62 23. -

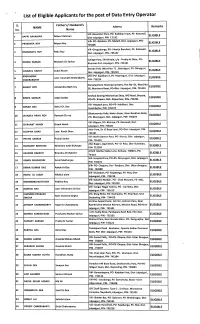

List of Eligible Applicants for the Post of Data Entry Operator

List of Eligible Applicants for the post of Data Entry Operator 51. Father's/ Husband's NAME Address Remarks No. Name ViII- Besandari Para, PO- Kadobari haat, PS-Katowali, Delwar Rahman ELIGIBLE 1 BAPPI RAHAMAN Dist- Jalpaiguri, PIN 7.5132 ViII+ PO- Batabari, PS-Matelli, Dist- Jalpaiguri, PIN- PRASANTA ROY Nripen Roy ELIGIBLE 2 735206 ViII- Ghugudanga, PO- Kharija Berubari, PS-Katowali, Padu Roy ELIGIBLE 3 DEBABRATA ROY Dist- Jalpaiguri, PIN- 735122 College Para, Shirishtola, c/o - Pradip Kr Dhar, Po- ROHINI SARKAR Bhabesh Ch 5arkar ELIGIBLE 4 Khariam Dist- Jalpaiguri, PIN- 735101 Saroda Pally (Ward No- 7) , Bairatiguri, PS-Dhupguri, SUSANTA RAHUT Subol Routh ELIGIBLE 5 Dist- Jalpaiguri, PIN- 735210 ANSHUMAN ViII+ Po- 5aptibari-2, PS-Maynaguri, Dist· Jalpaiguri, 6 Late- haranath Chakraborty ELIGIBLE CHAKRABORTY PIN-735224 Gurjang Jhora Housing Comlpex, Flat No- 01, Ward No ABHIJIT ROY Amalendra Nath roy ELIGIBLE 7 05, Marchant Road, PO+Dist- Jalpaiguri, PIN- 735101 Keshob Sewing Mechanical Shop, MG Road, Birpara, RIMPA SARKAR Jadav Sarkar ELIGIBLE 8 PO+PS-Birpara, Dist- Alipurduar, PIN- 735204 Vill- Hospital para, PO+PS-Haldibari, Dist- ARNAB DAS BakulCh.Das ELIGIBLE 9 Coochbehar, PIN- 735122 Bibekananda Pally, Natun Bazar, Near Bandhan Bank, JAYANTA PRIYA ROY Ramesh Ch roy ELIGIBLE 10 Po- Maynaguri, Dist- Jalpaiguri, PIN- 735224 ViII- Bilpara, PO- Khariya, PS-Katowali, Dist- CHIRANJIT NANDI Gopal Nandi ELIGIBLE 11 Jalpaiguri, PIN- 735101 Adar Para, Sir JCBose Lane, PO+Dist- Jalpaiguri, PIN- 12 SUDIPAN DHAR Late- Ranjit Dhar, ELIGIBLE -

DDRC Jalpaiguri10092018

5 4 3 2 1 SL.NO MIYA MIYA AKBAR ALI DHRUBA DHRUBA DUTTA PAYAL KHATUN PAYAL ANIMA ANIMA ROY PAYAL ROY PAYAL Name of beneficiary CAMP NAME : DDRC JALPAIGURI DATE : 10.09.2018 : DATE JALPAIGURI DDRC : NAME CAMP ROY,BARAKAMAT,JALPAIGUR TOLL,JAIGAON,JALPQAIGURI- PARA,BARUBARI,BERUBARI,J ROY,BAHADUR,JALPAIGURI- C/O C/O SAPIKUL ALAM,PURBA PARA,JALPAIGURI-735102 JAFOR,JAYGAON,TRIBENI JAFOR,JAYGAON,TRIBENI NAGAR,MOHANTA NAGAR,MOHANTA ALPAIGURI-735137 C/O C/O MIYA ABDUL DUTTA,MOHIT DUTTA,MOHIT C/O SHYAMAL C/O SHYAMAL C/O SANTOSH C/O SANTOSH LAL BAJAR C/O C/O BASI I-735305 735121 736182 Complete Address 14 14 48 65 11 Age M M F F F M/F GEN GEN OBC SC SC Caste 3500 3000 3000 3600 3000 Income HEARING HEARING HEARING HEARING HEARING AID V AID V AID V AID V AID V Type of aid(given) 10.09.2018 10.09.2018 10.09.2018 10.09.2018 10.09.2018 Date on Which (given) 5680 5680 5680 5680 5680 Total Cost of aid,including Fabrication/Fitment charges 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Subsidy provided Travel cost paid to outstation beneficiary Board and lodging expenses paid Whether any surgical correction undertaken 5680 5680 5680 5680 5680 Total of 10+11+12+13 No of days for which stayed Whether accomanied by escort YES YES YES YES YES Photo of beneficiary* 9002033171 9434228632 7076669744 9832340736 9932546247 Mobile No. or lan d line number with STD Code** C/O BABLU ROY,DHUPGURI,UTTAR HEARING 6 SIMA ROY 7 F SC 4000 10.09.2018 5680 100% 5680 YES 8512999121 KATHULIYA,JALPAIGURI- AID V 735210 C/O MADHUSUDAN APARNA CHAKRABORTY,ADARPARA HEARING 7 16 F GEN 2000 10.09.2018 5680 -

Chapter 4: CULTURAL RESOURCE STATUS of DHUPGURI BLOCK

Chapter 4: CULTURAL RESOURCE STATUS OF DHUPGURI BLOCK 4.1. Introduction Human resource of an area is considered to be of prime importance is achieving the overall efficiency and sustainability of natural resource management. Better human resource can utilized its natural resource base for the benefit of the society in a sustainable manner. Thus human resource often considered as the focal theme of assessing cultural resource of an area (Human Development Report, 200 I; WB Human Development Report, 2004). As mentioned earlier that the Dhupguri block consists of two parallel administrative set-up from the point of view of development planning under the light of 73'd and 74lh Constitution Amendments i.e., the PR!s that encompasses the rural area consisting of 16 gram pancheyets (GP) and ULBs that consists of Dhupguri municipality encompassing more urbanized area divided into 16 wards. An attempt has been made in this chapter to visualize the socio-economic status and the level of human resource development of Dhupguri block in the perspective of development planning. The data for such a study has mostly been accessed from the NRDMS centre Jalpaiguri, CCA village registrar and from the office of District Magistrate, Jalpaiguri. Necessary field verification has been carried out under standard format. Data has been analysed using standard statistical methods. 4.2 Socio-economic Status of Gram Paucheyets 4.2.1 Population and Family set-up The total population ofDhupguri block was estimated to be 309,729 according to CCA survey conducted in the year 2003-2004. Out of which 161, 511 (%)has been identified as male population and 146,218 (%) female population thus the gender ratio stands as 905.31 female population per 1000 male which is still lower than the national average. -

Chapter 2: GEOGRAPHIC SET-UP of DHUPGURI BLOCK

Chapter 2: GEOGRAPHIC SET-UP OF DHUPGURI BLOCK 2.1 Introduction The crescent shaped Dhupguri block (latitudes of 26° 54' to 26° 30'30" N and longitudes of 88° 52'30" to 89° 08' E) in Jalpaiguri district comprising an area of 544.10 sq. km. is elongated in north-south direction and is bordered by Nagrakata and Maynaguri in the east, Bhutan in the north, Birpara- Madarihat and Falakata blocks in the east and Kochbehar district in the south (Fig. 2.1 ). The block consists of 2 police stations, 16 Gram Pancheyets, 24 7 gram samsad and I 08 mauza including 22 tea garden mauza and 3 forest mauza. Out of the total population of 418461, 41.8% was schedule caste and 18.9% was schedule tribe population (2001 Census Report). In spite of its vast natural resource base, Dhupguri is among the backward block in the state. Besides, Dhupguri has its trove a vibrant melange of many a tribe and community, its enormous variety of wild life, amidst the grandiose and vast verdant forest. The international border with Bhutan and close proximity with Bangladesh accelerates the influx of migrants since independence that have demonstrated its adverse effects on society, economy and environment. Poor irrigation and agri-marketing facilities, lack of infrastructure, frequent flood and avulsion, lacks in human resource appreciation, rapid transformation of land-use for short-term benefit along with ad-hoc intervention with myopic view results in increasing frequency and magnitude of disasters in addition to the deterioration in quality of life. 2.2 Geology Dhupguri block is entirely underlain by alluvium except its northern border (with Bhutan) where hard rocks are exposed. -

SASEC Road Connectivity Investment Program – Tranche 1

Social Safeguard Due Diligence Report July 2017 IND: SASEC Road Connectivity Investment Program – Tranche 1 Prepared by Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, Government of India for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of May 2017) Currency unit – Indian Rupee (Rs) INR1.00 = $ 0.01555 $1.00 = INR 64.32 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BSR – Basic Schedule of Rates DC – District Collector DH – Displaced household DP – Displaced person EA – Executing Agency GRC – Grievance Redressal Committee IA – Implementing Agency IAY – Indira Awaas Yojana LA – Land acquisition LAA – Land Acquisition Act, 1894 L&LRO – Land and Land Revenue Office RFCT in LARR – The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Act - 2013 Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 LVC – Land Valuation Committee MORTH – Ministry of Road Transport and Highways NGO – Nongovernment organization NHA – National Highways Act, 1956 NRRP – National Rehabilitation and Resettlement Policy, 2007 PD – Project Director PIU – Project implementation unit MPWD – Manipur Public Works Department WBPWD – West Bengal Public Works (Roads) Department R&R – Resettlement and rehabilitation RF – Resettlement framework RO – Resettlement Officer ROW – Right-of-way RP – Resettlement plan SC – Scheduled caste SPS – Safeguard Policy Statement ST – Scheduled tribe NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This social due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

ATMA, Dated 20/12/2018 of ATMA, Uttar Dinajpur ADMIT CARD

AGRICULTURAL TECHNOLOGY MANAGEMENT AGENCY (A.T.M.A.), UTTAR DINAJPUR DISTRICT KARNAJORA : RAIGANJ : UTTAR DINAJPUR Advertisement No. : 3/ATMA, Dated 20/12/2018 of ATMA, Uttar Dinajpur ADMIT CARD To Roll No.1 /ATM Paste Self ANUBHAB DAS, S/O-MURATI MOHAN DAS Attested VILL+ P.O – GOALTORE, Stamp Size DIST- PASCHIM MIDINIPUR, PIN-733123 Photograph Name of the Post :- Assistant Technology Manager (ATM) Date :-26.02.2019 . Venue :- District Panchayet Training Resource Centre (DPTRC) Conference Hall, Karnajora, Raiganj , Uttar Dinajpur. Time :- 10.00 A.M. Onwards. Reporting Time :- 9.30 A.M. You are requested to report at the specified venue, date and time for attending interview & computer test for the Contractual post of Assistant Technology Manager (ATM). _______________________________ _______________________________ Documents verified by (Full Signature) Full Signature of the candidate _______________________________________ Chairman, Recruitment Committee For Instruction and terms & conditions please see overleaf ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… AGRICULTURAL TECHNOLOGY MANAGEMENT AGENCY (A.T.M.A.), UTTAR DINAJPUR DISTRICT KARNAJORA : RAIGANJ : UTTAR DINAJPUR Advertisement No. : 3/ATMA, Dated 20/12/2018 of ATMA, Uttar Dinajpur ADMIT CARD To Roll No.1 /ATM Paste Self ANUBHAB DAS, S/O-MURATI MOHAN DAS Attested VILL+ P.O – GOALTORE, Stamp Size DIST- PASCHIM MIDINIPUR, PIN-733123 Photograph Name of the Post :- Assistant Technology Manager (ATM) Date :-26.02.2019 . Venue :- District Panchayet Training Resource Centre (DPTRC) Conference Hall, Karnajora, Raiganj , Uttar Dinajpur. Time :- 10.00 A.M. Onwards. Reporting Time :- 9.30 A.M. You are requested to report at the specified venue, date and time for attending interview & computer test for the Contractual post of Assistant Technology Manager (ATM).