Paper SH/Fall/05

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: a Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: A Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A. Johnson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC LOGGING SONGS OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST: A STUDY OF THREE CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS By LESLIE A. JOHNSON A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Leslie A. Johnson defended on March 28, 2007. _____________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member ` _____________________________ Karyl Louwenaar-Lueck Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank those who have helped me with this manuscript and my academic career: my parents, grandparents, other family members and friends for their support; a handful of really good teachers from every educational and professional venture thus far, including my committee members at The Florida State University; a variety of resources for the project, including Dr. Jens Lund from Olympia, Washington; and the subjects themselves and their associates. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. -

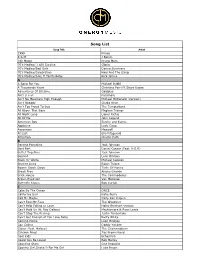

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

The All American Boy

The All American Boy His teeth I remember most about him. An absolutely perfect set kept totally visible through the mobile shutter of a mouth that rarely closed as he chewed gum and talked, simultaneously. A tricky manoeuvre which demanded great facial mobility. He was in every way the epitome of what the movies, and early TV had taught me to think of as the “All American Boy”. Six foot something, crew cut hair, big beaming smile, looked to be barely twenty. His mother must have been very proud of him! I was helping him to refuel the Neptune P2V on the plateau above Wilkes from numerous 44 gallon drums of ATK we had hauled to the “airstrip” on the Athey waggon behind a D4 driven by Max Berrigan. I think he was an aircraft mechanic. He and eight of his compatriots had just landed after a flight from Mirny, final stop McMurdo. Somehow almost all of the rest of his crew, and ours, had hopped into the weasels to go back to base for a party, leaving just a few of us “volunteers” to refuel. I remember too, feeling more than a little miffed when one of the first things he said after our self- introductions was “That was one hell of a rough landing strip you guys have - nearly as bad as Mirny”. Poor old Max had ploughed up and down with the D4 for hours knocking the tops of the Sastrugi and giving the “strip” as smooth a surface as he could. For there was not really a strip at Wilkes just a slightly flatter area of plateau defined by survey pegs. -

Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films

South Asian Popular Culture ISSN: 1474-6689 (Print) 1474-6697 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsap20 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard To cite this article: Dickens Leonard (2015) Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films, South Asian Popular Culture, 13:2, 155-173, DOI: 10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Published online: 23 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsap20 Download by: [University of Hyderabad] Date: 25 October 2015, At: 01:16 South Asian Popular Culture, 2015 Vol. 13, No. 2, 155–173, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard* Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India This paper analyses contemporary, popular Tamil films set in Madurai with respect to space and caste. These films actualize region as a cinematic imaginary through its authenticity markers – caste/ist practices explicitly, which earlier films constructed as a ‘trope’. The paper uses the concept of Heterotopias to analyse the recurrence of spectacle spaces in the construction of Madurai, and the production of caste in contemporary films. In this pursuit, it interrogates the implications of such spatial discourses. Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films To foreground the study of caste in Tamil films and to link it with the rise of ‘caste- gestapo’ networks that execute honour killings and murders as a reaction to ‘inter-caste love dramas’ in Tamil Nadu,1 let me narrate a political incident that occurred in Tamil Nadu – that of the formation of a socio-political movement against Dalit assertion in December 2012. -

Mayjune 2005 Social Ed.Indd

Social Education 69(4), pp. 189-192 © 2005 National Council for the Social Studies Reel to Real: Teaching the Twentieth Century with Classic Hollywood Films Karl A. Matz and Lori L. Pingatore Making students’ learning cal artifacts, virtually primary source docu- works to support all three. At work, Bow experiences as direct and real as possible ments, that are very easy to obtain and yet has caught the eye of a wealthy young man, has always been challenging for educators. are too rarely used. Here, we hope to give a friend of the store owner’s son. In this Ancient wars and forgotten statesmen teachers a sense of which films are most brief beginning to a feature length film, often hold little excitement for students. appropriate and to provide a workable viewers see three important locations as Innovative teachers often use artifacts and method for guiding students to critically they were in the late 1920s. We see the primary source documents to transform a examine these historical artifacts. downtown department store, so different vicarious learning experience to a much from the suburban malls we know today. more direct one. Lee Ann Potter observes Celluloid Anthropology We see the humble apartment, the decora- that primary source documents “allow us, Students can study films in a manner simi- tions, and the absence of technology. And, quite literally, to touch and connect with lar to the way an anthropologist studies a finally, we see the restaurant. the past.”1 culture. If we were to study the culture of While watching this film, as any Films, like artifacts and photographs, a community in the Brazilian rainforest, other movie of a different era, viewers can also bring students closer to the people we would observe social rules, modes of can observe manners and behaviors, note and events that they are studying. -

Download This Report

A LICENSE TO KILL Israeli Operations against "Wanted" and Masked Palestinians A Middle East Watch Report Human Rights Watch New York !!! Washington !!! Los Angeles !!! London Copyright 8 July 1993 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number: 93-79007 ISBN: 1-56432-109-6 Middle East Watch Middle East Watch was founded in 1989 to establish and promote observance of internationally recognized human rights in the Middle East. The chair of Middle East Watch is Gary Sick and the vice chairs are Lisa Anderson and Bruce Rabb. Andrew Whitley is the executive director; Eric Goldstein is the research director; Virginia N. Sherry and Aziz Abu Hamad are associate directors; Suzanne Howard is the associate. HUMAHUMAHUMANHUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch conducts regular, systematic investigations of human rights abuses in some sixty countries around the world. It addresses the human rights practices of governments of all political stripes, of all geopolitical alignments, and of all ethnic and religious persuasions. In internal wars it documents violations by both governments and rebel groups. Human Rights Watch defends freedom of thought and expression, due process of law and equal protection of the law; it documents and denounces murders, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment, exile, censorship and other abuses of internationally recognized human rights. Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of Helsinki Watch by a group of publishers, lawyers and other activists and now maintains offices in New York, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, London, Moscow, Belgrade, Zagreb and Hong Kong. -

C.S. Lewis's Humble and Thoughtful Gift of Letter Writing

KNOWING . OING &DC S L EWI S I N S TITUTE Fall 2013 A Teaching Quarterly for Discipleship of Heart and Mind C.S. Lewis’s Humble and Thoughtful Gift of Letter Writing by Joel S. Woodruff, Ed.D. Vice President of Discipleship and Outreach, C.S. Lewis Institute s it a sin to love Aslan, the lion of Narnia, Recalling your tears, I long to see you, so that more than Jesus? This was the concern ex- I may be filled with joy” (2 Tim. 1:2–4 NIV). Ipressed by a nine-year-old American to his The letters of Paul, Peter, John, James, and Jude mother after reading The Chronicles of Narnia. that fill our New Testament give witness to the IN THIS ISSUE How does a mother respond to a question like power of letters to be used by God to disciple that? In this case, she turned straight to the au- and nourish followers of Jesus. While the let- 2 Notes from thor of Narnia, C.S. Lewis, by writing him a let- ters of C.S. Lewis certainly cannot be compared the President ter. At the time, Lewis was receiving hundreds in inspiration and authority to the canon of the by Kerry Knott of letters every year from fans. Surely a busy Holy Scriptures, it is clear that letter writing is scholar, writer, and Christian apologist of inter- a gift and ministry that when developed and 3 Ambassadors at national fame wouldn’t have the time to deal shared with others can still influence lives for the Office by Jeff with this query from a child. -

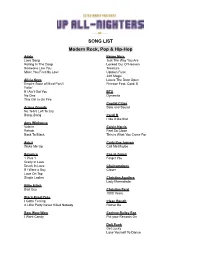

Band Song-List

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

Encore Songlist

west coast music Encore Please find attached the Encore Band song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need to have your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, F/D Dance, etc) FOUR WEEKS prior to your event so that we can confirm the band will be able to perform the song(s) and so that we have time to locate sheet music and audio of the song(s). In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is needed, this gives us time to properly prepare the music. Clients are not obligated to submit a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and/or avoided. If you desire the highest degree of control (asking the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we would ask for a minimum 80 requests from the band’s songlist. Please feel free to call us at the office should you have any questions. – West Coast Music SONGLIST: At Last – Etta James 1,2,3,4 – Plain White T’s Baby Got Back – Sir Mix A Lot 24K Magic – Bruno Mars Back at One – Boyz II Men A Thousand Years – Christina Bad Day – Daniel Powter Perri Ballad Of John & Yoko Ain’t too Proud to Beg – Bamboleo – Gipsy Kings Temptations Bang my Head – David Guetta/Sia Adventure of a Lifetime – Beast of Burden – Rolling Stones Coldplay Beautiful Day – U2 After All – Peter Cetera/Cher -

Most Requested Songs of 2009

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on nearly 2 million requests made at weddings & parties through the DJ Intelligence music request system in 2009 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 4 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 5 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 6 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 7 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 8 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 9 B-52's Love Shack 10 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 11 ABBA Dancing Queen 12 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 13 Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow 14 Rihanna Don't Stop The Music 15 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 16 Outkast Hey Ya! 17 Sister Sledge We Are Family 18 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 19 Kool & The Gang Celebration 20 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 21 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 22 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 23 Lady Gaga Poker Face 24 Beatles Twist And Shout 25 James, Etta At Last 26 Black Eyed Peas Let's Get It Started 27 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 28 Jackson, Michael Thriller 29 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 30 Mraz, Jason I'm Yours 31 Commodores Brick House 32 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 33 Temptations My Girl 34 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 35 Vanilla Ice Ice Ice Baby 36 Bee Gees Stayin' Alive 37 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 38 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

Karla Chisholm Just Squeeze Me (Jane Monheit) Mas Que Nada (Brazil 66) Sample Song-List Route 66 (Chuck Berry Arr.)

I’ve Got The World On A String (Sarah Vaughn) Karla Chisholm Just Squeeze Me (Jane Monheit) Mas Que Nada (Brazil 66) Sample Song-List Route 66 (Chuck Berry Arr.) Somewhere Over The Rainbow (Israel JAZZ Kamakawiwo'ole) Summertime (Ella Fitzgerald) Ain’t Misbehavin (Fats Waller) Sway (Michael Buble) All or Nothing At All (Diana Krall) That’s All (Sarah Vaughn) Autumn Leaves (Nat King Cole) The Way You Look Tonight (Frank Sinatra) Between The Devil and the Deep Blue Sea (Ella Fitzgerald) They Can’t Take That Away From Me (Natalie Cole) Bewitched (Ella Fitzgerald) This Can’t Be Love (Sarah Vaughn) Corcovado (Antonio Carlos Jobim) Time After Time (Nancy Wilson) Dance Me To The End of Love (Madeleine Peyrox) Unforgettable (Natalie Cole and Nat King Cole) Dindi (Antonio Carlos Jobim) What A Wonderful World (Louis Armstrong) Don't get Around Much Anymore Fever (Peggy Lee) POP Fly Me To The Moon (Frank Sinatra) At Last (Etta James) Georgia (Ray Charles) All About That Bass (Postmodern Jukebox) Girl From Ipanema (Antonio Carlos Jobim in Portuguese & English) All Of Me (Postmodern Jukebox) I Love Being Here With You (Peggy Lee) American Boy (Estelle) It Had To Be You (Frank Sinatra) Back to Black (Amy Whinehouse) I’m Beginning to See the Light (Ella Fitzgerald) Bennie and the Jets (Elton John) It Had To Be You (Frank Sinatra) Billie Jean (The Civil Wars) 2217 Distribution Circle Silver Spring, MD 20910-1260 (301) 986-4640 (888) 986-4640 FAX (301) 657-4315 www.entertainmentexchange.com 2 Blank Space (Taylor Swift) If I Could Change The World (Eric -

Understanding Consumers' Perceptions and Behaviors: Implications for Denim Jeans Design

Volume 7, Issue 1, Spring2011 Understanding Consumers’ Perceptions and Behaviors: Implications for Denim Jeans Design Osmud Rahman, Assistant Professor School of Fashion, Ryerson University, Toronto [email protected] ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to uncover the relative salient of intrinsic and extrinsic cues as determinants of consumers’ purchasing intent toward denim jeans. To the best of my knowledge, there is no comprehensive study reporting results from Canadian consumers’ perspective regarding their perceptions and behaviors toward denim jeans. A self-administered survey with Likert scale and open-ended questions were used for this study. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to analyze the salient factors and the correlation of six intrinsic cues and three extrinsic cues of denim jeans. A total of 380 useable surveys were compiled, analyzed and collated. The results of this study revealed that fit of denim jeans was the most important cue followed by style and quality, whereas brand names and country-of-origin were relatively insignificant. In terms of product cue correlation, fabric was strongly correlated with style, comfort and quality. Intrinsic cues played a more significant role on denim jeans evaluation than extrinsic cues. According to the results of this study, young consumers tended to use various product attributes to fulfill their concrete needs and abstract aspirations. Keywords: Denim jeans, consumer purchasing, Canadian consumers Introduction commodity and a means of cultural expression. By the 1950s, jeans became the The symbolic meanings of denim symbol of teenage rebellion influenced by jeans have evolved since the California Gold television programs and movies such as The Rush era of the 1850‟s.