Master Document Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Zhu, Yingyue Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 14:07:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/642043 MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING by Yingyue Zhu ____________________________ Copyright © Yingyue Zhu 2020 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Master’s Committee, we certify that we have read the thesis prepared by Yingyue Zhu, titled MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Master’s Degree. Jun 29, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Dian Li Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Scott Gregory Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the thesis to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this thesis prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Master’s requirement. -

Notes Made in China in May 1990 for the BBC Radio Documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy* Gregory B

Notes made in China in May 1990 for the BBC radio documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy* Gregory B. Lee To cite this version: Gregory B. Lee. Notes made in China in May 1990 for the BBC radio documentary *The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy*. 2019. hal-02196338 HAL Id: hal-02196338 https://hal-univ-lyon3.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02196338 Preprint submitted on 28 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Gregory B. Lee. URGENT KNOCKING, China/Hong Kong Notebook, May 1990. Notes made in China in May 1990 in connection with the hour-long radio documentary The Urgent Knocking: New Chinese Writing and the Movement for Democracy which I was making for the BBC and which was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on 4the June 1990 to coincide with the 1st anniversary of the massacre at Tiananmen. My Urgent Knocking notebook is somewhat cryptic. I was worried about prying eyes, and the notes were not made in chronological, or consecutive order, but scattered throughout my notebook. Probably, I was hoping that their haphazard pagination would withstand a cursory inspection. -

Gregory Lee CV 1

Gregory Lee CV Curriculum vitae GREGORY B. LEE 利大英 Professor of Chinese and Transcultural Studies, Université de Lyon – Jean Moulin (since 1999) Director, Institut d’Etudes Transtextuelles et Transculturelles (Institute for Transtextual and Transcultural Studies — IETT) Fellow of the Hong Kong Academy of the Humanities Chevalier de l’ordre des Palmes académiques Nationalities: British & French Languages: English (native), Chinese (near native), French (near native); Spanish (good); Portuguese, Italian (reading) PREVIOUS AND VISITING POSTS 05.2018 ; 03.2019 Visiting Professor, Sun Yat-sen University, Canton, China 2010-2012 Chair Professor of Chinese & Transcultural Studies, City University of Hong Kong Founding Director, Hong Kong Advanced Institute for Cross-Disciplinary Studies 2005-2010 Honorary Visiting Professor, University of Wuhan, China 1998-1999 Visiting Professor, University of Lyon (Jean Moulin) 1994-1998 Associate Professor, Department of Comparative Literature, University of Hong Kong 1990-1994 Assistant Professor, East Asian Languages & Civilizations, University of Chicago 1987-1988 Lecturer (temporary), Department of East Asia School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 1983-1984 Supervisor, Faculty of Oriental Studies Cambridge University OTHER PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 1988-1990 Asia Specialist (report writer and broadcaster), BBC World Service 1986-1987 Editor, Foreign Languages Press (SINOLINGUA Chinese as a second language), Beijing 1983-1984 Acting Head, Far Eastern Library, Cambridge University 1 Gregory -

Two Poems Chen Li Translated by Elaine Wong

Special Focus Chinese Contemporary Poetry Two Poems Chen Li Translated by Elaine Wong The two poems included here are from Elaine Wong’s project translating Chen Li’s poetry. “I Run into Monet in Monet’s Garden” imagines a conversation with Monet on the redemptive power of art in times of personal suffering. Wong’s recent viewing of the wall-sized Water Lilies by Monet at the Met brought some breakthroughs to this translation, especially to the wordplay on “water lily” and to the transition from pain to beauty. “Rivers North of the Future” portrays Chen Li’s friendship with the Beijing poet Wang Jiaxin as well as his aspiration for sincere poetic exchanges between Taiwan and mainland China. Meeting both poets in summer 2018 helped Wong better understand the poets’ relationship and their poems. CHINESE LITERATURE TODAY VOL . 8 NO . 1 97 I Run into Monet in Monet’s Garden I run into Monet in Monet’s Garden. He asks, “Did But your eyesight is deteriorating. (Is there you come a cataract?) from the Orangerie, where lianhua ponds line the Can you see light sharply with your eyes? oval walls?” “I also use my mind’s eye. I can see I say, I came from Hualien, the opposite direction. the wrinkles in flowing water. That Your is immortal youth . ” Japanese footbridge brought me here. You came up I came under physical and emotional pain, against and encountered a depression as heavy, or light, poverty, and you lost two wives and your eldest son as ocean and sky blue. Can I turn Hualien, my in his prime. -

Read the Introduction

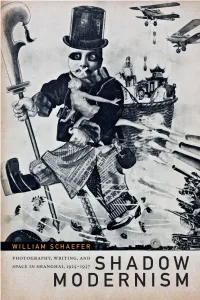

William Schaefer PhotograPhy, Writing, and SPace in Shanghai, 1925–1937 Duke University Press Durham and London 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schaefer, William, author. Title: Shadow modernism : photography, writing, and space in Shanghai, 1925–1937 / William Schaefer. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and ciP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017007583 (print) lccn 2017011500 (ebook) iSbn 9780822372523 (ebook) iSbn 9780822368939 (hardcover : alk. paper) iSbn 9780822369196 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcSh: Photography—China—Shanghai—History—20th century. | Modernism (Art)—China—Shanghai. | Shanghai (China)— Civilization—20th century. Classification: lcc tr102.S43 (ebook) | lcc tr102.S43 S33 2017 (print) | ddc 770.951/132—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007583 Cover art: Biaozhun Zhongguoren [A standard Chinese man], Shidai manhua (1936). Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries. Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of Rochester, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures and the College of Arts, Sciences, and Engineering, which provided funds toward the publication -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Copyright Service. sydney.edu.au/copyright 1 The Noose Among the Cherries: Landscape and the Representation of Resident Koreans in Japanese Film By Michael Ward A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Sciences The University of Sydney 2015 2 Dedication Page This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my beloved father Billy F. Ward (November 30, 1945-August 16, 2014) who passed away only twelve days before I submitted this thesis for examination. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Dreams and disillusionment in the City of Light : Chinese writers and artists travel to Paris, 1920s-1940s Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/07g4g42m Authors Chau, Angie Christine Chau, Angie Christine Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Dreams and Disillusionment in the City of Light: Chinese Writers and Artists Travel to Paris, 1920s–1940s A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Angie Christine Chau Committee in charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair Professor Larissa Heinrich Professor Paul Pickowicz Professor Meg Wesling Professor Winnie Woodhull Professor Wai-lim Yip 2012 Signature Page The Dissertation of Angie Christine Chau is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ...................................................................................................................iii Table of Contents............................................................................................................... iv List of Illustrations.............................................................................................................. v Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... -

Literature and the Pictorial Magazine

Chapter 1 Literature and the Pictorial Magazine An Introduction to Writers and Writings in Wenyi and Wanxiang The short-lived magazines Wenyi and Wanxiang were just two of many dedicated to the latest movements in art and literature that appeared in 1934, an unprecedented year for the Shanghai magazine publishing industry that became known as The Year of the Magazine.1 The magazines included essays on art and literature from Europe, America, and Japan, with short sto- ries by Chinese writers and translations into Chinese of writings by foreign authors. Ye Lingfeng 葉靈鳳 (1905–1975) and Mu Shiying, both associated with the New-sensationist group of writers (Mu as a central figure and Ye on its fringes) were the chief editors of Wenyi, a magazine described by their col- league Hei Ying in later years as a ‘pure art and literature publication’, in other words a magazine dedicated to ‘art for art’s sake’.2 The products of the writ- ers associated with this group consciously adopted traits of the writing of the Shinkankaku-ha, the Japanese New-sensationists, whose work had been intro- duced to China by Liu Na’ou in the 1920s, as well as aspects of the writings of the French modernist Paul Morand (1888–1976), who had already been such an inspiration to the Japanese group in the early part of that decade.3 In common with many other writers and artists in Shanghai during the 1930s, one of the aims of these Chinese writers was to break down barriers that were seen to exist between ‘high’ and ‘low’ cultures, with the result that their work takes on many of the trappings of popular cultural imagery, while at the same time retaining what might be described as its ‘avant-garde’, modern- ist nature. -

THE BATTLE of HONG KONG Belligerents

THE BATTLE OF HONG KONG DATE: DECEMBER 08 – DECEMBER 25 1941 Belligerents Japan United Kingdom Hong Kong India Canada China Free French The Battle of Hong Kong was fought between December 8 - 25, 1941. As the Second Sino-Japanese War raged between China and Japan during the late 1930s, Great Britain was forced to examine its plans for the defense of Hong Kong. In studying the situation, it was quickly found that the colony would be difficult to hold in the face of a determined Japanese attack. Despite this conclusion, work continued on a new defensive line extending from Gin Drinkers Bay to Port Shelter. Begun in 1936, this set of fortifications was modeled on the French Maginot Line and took two years to complete. Centered on the Shin Mun Redoubt, the line was a system of strong points connected by paths. In 1940, with World War II consuming Europe, the government in London began reducing the size of the Hong Kong garrison to free troops for use elsewhere. Following his appointment as Commander-in-Chief of the British Far East Command, Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham requested reinforcements for Hong Kong as he believed even a marginal increase in the garrison could significantly slow down the Japanese in the case of war. Though not believing that the colony could be held indefinitely, a protracted defense would buy time for the British elsewhere in the Pacific. FINAL PREPARATIONS In 1941, Prime Minister Winston Churchill agreed to dispatch reinforcements to the Far East. In doing so, he accepted an offer from Canada to send two battalions and a brigade headquarters to Hong Kong. -

China's Post-Second World War Trials of Japanese War Criminals, 1946

Historical Origins of International Criminal Law: Volume 2 Morten Bergsmo, CHEAH Wui Ling and YI Ping (editors) PURL: http://www.legal-tools.org/doc/76e925/ E-Offprint: ZHANG Tianshu, “The Forgotten Legacy: China’s Post-Second World War Trials of Japanese War Criminals, 1946–1956”, in Morten Bergsmo, CHEAH Wui Ling and YI Ping (editors), Historical Origins of International Criminal Law: Volume 2, FICHL Publication Series No. 21 (2014), Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, Brussels, ISBN 978-82-93081-13-5. First published on 12 December 2014. This publication and other TOAEP publications may be openly accessed and downloaded through the website www.fichl.org. This site uses Persistent URLs (PURL) for all publications it makes available. The URLs of these publications will not be changed. Printed copies may be ordered through online distributors such as www.amazon.co.uk. © Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2014. All rights are reserved. PURL: http://www.legal-tools.org/doc/76e925/ 29 ______ The Forgotten Legacy: China’s Post-Second World War Trials of Japanese War Criminals, 1946–1956 ZHANG Tianshu* 29.1. Introduction Alongside the trial of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (‘IMTFE’) held in Tokyo against Class A war criminals, the national trials involving Class B and C Japanese war criminals were conducted in the territory of states with which Japan had been at war, including China, Korea, the Philippine and others. In 1946 the Nationalist government of the Republic of China (‘ROC’) held the trials of Japanese war criminals in ten cities. The ROC trials sentenced 145 Japanese war criminals to death and 300 to limited or lifetime imprisonment. -

Xu Zhimo's Encounter with »A Jewish Nightmare«—How a Chinese

Xu Zhimo’s Encounter with »A Jewish Nightmare«—How a Chinese Symbolist Viewed an Expressionist Yiddish Play Victor Vuilleumier In March 1925, the poet Xu Zhimo 徐志摩 (1896–1931) took the Trans-Siberian train, crossed Siberia and visited Russia on his second trip to Europe. He returned to China in August after his visit to Italy, France and England. 1 Around May, while traveling, he wrote a series of essays (sanwen 散文)2 mainly on the Russian part of his journey. These writings were serialized between June and August of the same year in a popular magazine, the Morning Post Supplement (Chenbao fukan 晨報副刊, Beijing).3 His essays are entitled Casual Notes on My European Tour (»Ouyou manlu« 歐遊漫錄) and more accurately subtitled Travelogue about Siberia (»Xiboliya youji« 西伯利亞遊 記); they would later be included in a Xu Zhimo collection of essays, Auto-Section (Zipou 自剖, 1928).4 One of them is entitled A Jewish Nightmare (»Youtairen de bumeng« 猶太人的怖夢). It describes a performance Xu Zhimo had attended during his stay in Moscow. He said he had initially planned to attend two plays performed by the Moscow Art Theatre, namely, Hamlet and a play by Chesterton. However, their staging was put off because of the funeral of an official, »Mr Malimahu« (173).5 There was only a »newly established 1 Cf. Leo Lee Ou-fan [Li Oufan 李歐梵], The Romantic Generation of Modern Chinese Writers (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973), 124–174. 2 According to Xu Zhimo quanji 徐志摩全集 [The Complete Works of Xu Zhimo], 5 vols. (Nanning: Guangxi minzu chubanshe, 1991), 3: 3. -

Purity, Modernity, and Pessimism :: Translation of Mu Shiying's Fiction/ Rui Tao University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2000 Purity, modernity, and pessimism :: translation of Mu Shiying's fiction/ Rui Tao University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Tao, Rui, "Purity, modernity, and pessimism :: translation of Mu Shiying's fiction/" (2000). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2024. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2024 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PURITY, MODERNITY, AND PESSIMISM TRANSLATION OF MU SHIYING'S FICTION A Thesis Presented by RUI TAO Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2000 Department of Asian Languages and Literatures PURITY, MODERNITY, AND PESSIMISM TRANSLATION OF MU SHIYING'S FICTION A Thesis Presented by RUI TAO Approved as to style and content by Donald Gjertson, Chair DpfisJBargen, Member YaohuajShi, Member 0 Chisato Kitagawa, Department head Department of Asian language & Literatures ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to members of the committee, Dr. Donald Gjertson, Dr. Doris Bargen and Dr. Yaohua Shi, for their patient guidance and support. I would also like to thank my American sister, Lindsley Cameron, who took time to read the manuscript and provided valuable feedback on it. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, my sister and my brother for then- priceless support.