PART THREE the Later Commissioner Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dupont Circle Neighborhood Focuses on the History and Architecture of Part of Our Local Environment That Is Both Familiar and Surprising

Explore historic d Explore historic CHILDREN’S WALKING TOUR CHILDREN’S EDITION included DUPONT CIRCLE inside! NEIGHBORHOOD WASHINGTON, DC © Washington Architectural Foundation, 2018 Welcome to Dupon Welcome to Welcome This tour of Washington’s Dupont Circle Neighborhood focuses on the history and architecture of part of our local environment that is both familiar and surprising. The tour kit includes everything a parent, teacher, Scout troop leader, or homeschooler would need to walk children through several blocks of buildings and their history and to stimulate conversation and activities that build on what they’re learning. Designed for kids in the 8-12 age group, the tour is fun and educational for older kids and adults as well. The tour materials include... • History of Dupont Circle • Tour Booklet Instructions • Dupont Circle Neighborhood Guide • Architectural Vocabulary • Conversation Starters • Dupont Circle Tour Stops • Children's Edition This project has been funded in part by a grant from HumanitiesDC, an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. This version of the Dupont Circle Neighborhood children’s walking tour is the result of a collaboration among Mary Kay Lanzillotta, FAIA, Peter Guttmacher, and the creative minds at LookThink, with photos courtesy of Ronald K. O'Rourke and Mary Fitch. We encourage you to tell us about your experience using this children's architecture tour, what worked really well and how we can make it even better, as well as other neighborhoods you'd like to visit. Please email your comments to Katherine Adams ([email protected]) or Mary Fitch ([email protected]) at the Washington Architectural Foundation. -

![Agnes Elizabeth Ernst Meyer Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1173/agnes-elizabeth-ernst-meyer-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-2521173.webp)

Agnes Elizabeth Ernst Meyer Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Agnes Elizabeth Ernst Meyer Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2014 Revised 2018 April Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms014057 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm89049593 Prepared by Manuscript Division Staff Collection Summary Title: Agnes Elizabeth Ernst Meyer Papers Span Dates: 1853-1972 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1906-1970) ID No.: MSS49593 Creator: Meyer, Agnes Elizabeth Ernst, 1887-1970 extent: 70,000 items ; 201 containers plus 1 oversize ; 90 linear feet ; 2 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Author and social activist. Correspondence, diaries, speeches, writings including an unpublished memoir, subject files, research material, family papers, and other papers relating to Meyer's career as an author, authority on Asian art, literary critic and linguist, and social activist as well as to her personal and family life. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Alinsky, Saul David, 1909-1972--Correspondence. Ashmore, Harry S.--Correspondence. Block, Herbert, 1909-2001--Correspondence. Boyd, Julian P. (Julian Parks), 1903-1980--Correspondence. Brandeis, Louis Dembitz, 1856-1941. Brown, J. Carter (John Carter), 1934-2002--Correspondence. Cardozo, Benjamin N. (Benjamin Nathan), 1870-1938. Carson, Rachel, 1907-1964--Correspondence. -

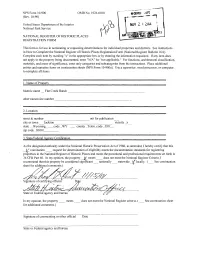

Flat Creek Ranch National Register Form.Pdf

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name _ Flat Creek Ranch other names/site number 2. Location street & number ____ not for publication city or town __Jackson vicinity x state _Wyoming_ code WY county _Teton_code _039 zip code ^83001_ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this (/ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property V meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant __ nationally __ statewide _j£ locally. -

The Antitrust Legacy of Thurman Arnold Spencer Weber Waller Loyola University Chicago, School of Law, [email protected]

Loyola University Chicago, School of Law LAW eCommons Faculty Publications & Other Works 2004 The Antitrust Legacy of Thurman Arnold Spencer Weber Waller Loyola University Chicago, School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/facpubs Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Legal Biography Commons Recommended Citation Waller, Spencer Weber, The Antitrust Legacy of Thurman Arnold, 78 St. John’s L. Rev. 569 (2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ANTITRUST LEGACY OF THURMAN ARNOLD SPENCER WEBER WALLERt INTRODUCTION No one will ever know exactly why Franklin Roosevelt hired Thurman Arnold as head of the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department in 1938. It may simply have been that head of the Antitrust Division was the first important administration job available when Arnold's supporters and friends sought a full- time Washington position for him.1 While the nomination proved to be an awkward and controversial choice, it was also an inspired choice. For the next five years, Thurman Arnold revitalized antitrust law and enforcement and changed the entire focus of the New Deal from corporatist planning to competition as the fundamental economic policy of the Roosevelt administration. Those who favor a consumer-friendly competitive economy owe him a debt that transcends the specific cases he brought and the doctrines he espoused. This Article is a look at that legacy. -

In This Issue

The Ol’ Pioneer The Magazine of the Grand Canyon Historical Society Volume 24 : Number 1 www.GrandCanyonHistory.org Winter 2013 In This Issue Citizen Kane-yon ....... 3 President’s Letter The Ol’ Pioneer The Magazine of the Greetings All GCHS Members and GCHS Friends! Grand Canyon Historical Society As your newly elected president I am honored to help lead this fantastic or- Volume 24 : Number 1 ganization into the future. At our last board meeting, there was palpable excite- Winter 2013 ment in the air about our future as one of the primary organizations concerned with the documentation and recording of Grand Canyon’s dynamic human his- u tory. I want you to know that your officers are dedicated to making this an even The Historical Society was established better Society in the future, that will evolve and change, much as the canyon in July 1984 as a non-profit corporation landscape has done over the last 6 million years (or is that 70 million?). There to develop and promote appreciation, is a new energy among the officers that will drive our ambitions forward as we understanding and education of the prepare for the next symposium in 2017. But four promising years lie between earlier history of the inhabitants and important events of the Grand Canyon. us and that date with destiny and we will not be idle until that day. Some of the goals we have in mind are to publish the 3rd Symposium papers in either The Ol’ Pioneer is published by the “print-on-demand” form or the old fashioned book route; the possible initia- GRAND CANYON HISTORICAL tion of an Oral History Project”; some initiatives on finding a broader range of SOCIETY in conjunction with The articles for The Ol’ Pioneer (with all deference to our everlasting hero Don Lago); Bulletin, an informational newsletter. -

Legacy Finding Aid for Manuscript and Photograph Collections

Legacy Finding Aid for Manuscript and Photograph Collections 801 K Street NW Washington, D.C. 20001 What are Finding Aids? Finding aids are narrative guides to archival collections created by the repository to describe the contents of the material. They often provide much more detailed information than can be found in individual catalog records. Contents of finding aids often include short biographies or histories, processing notes, information about the size, scope, and material types included in the collection, guidance on how to navigate the collection, and an index to box and folder contents. What are Legacy Finding Aids? The following document is a legacy finding aid – a guide which has not been updated recently. Information may be outdated, such as the Historical Society’s contact information or exact box numbers for contents’ location within the collection. Legacy finding aids are a product of their times; language and terms may not reflect the Historical Society’s commitment to culturally sensitive and anti-racist language. This guide is provided in “as is” condition for immediate use by the public. This file will be replaced with an updated version when available. To learn more, please Visit DCHistory.org Email the Kiplinger Research Library at [email protected] (preferred) Call the Kiplinger Research Library at 202-516-1363 ext. 302 The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is a community-supported educational and research organization that collects, interprets, and shares the history of our nation’s capital. Founded in 1894, it serves a diverse audience through its collections, public programs, exhibits, and publications. 801 K Street NW Washington, D.C. -

SUMMER 2016 Celebrating the Countess of Flat Creek!

Historical Society & Museum Chronicle VOLUME XXXVI NO. 2 SUMMER 2016 Celebrating the Countess of Flat Creek! Neither thunder, lightning nor buckets and buckets of rain dampened the spirits of the 250-plus who came out to celebrate the naming of JHHSM’s Cissy Patterson Gallery at 225 N. Cache on July 10th. Until then the main exhibit gallery at our Homestead Museum had simply been referred to as ‘the Cache Street gallery’. Descriptive, but perhaps not very inspiring. Now, thanks to a generous grant from the Cissy Patterson Foundation, the gallery has a new name, additions to its existing displays on homesteading, cattle and dude ranching, hunting and outfitting - and a focus on one of the valley’s most intriguing and colorful historical figures: Elinor Medill Patterson, known to her family and friends as “Cissy”, arrived in Jackson Hole with her maid to spend time at the Bar B C dude ranch in the summer of 1917. Joe Albright, Cissy’s great nephew, presided over the ribbon cutting and shared with the crowd that the downpour that threatened to short out the museum’s sound system was only fitting - as Cissy herself had first come to Jackson Hole in just such a deluge. Having traveled over Teton pass by horseback from the Eleanor “Cissy” Medill Patterson train station in Victor, Idaho, Cissy arrived tired, wet and bedraggled, and more than a little irritable. The young socialite from a prestigious publishing family in Chicago determined to leave as soon the rain stopped. Demanding room service and a hot bath in her cabin, she was informed that the Bar B C offered neither and that the horses were too tired to travel anyway – it would be 2 weeks before she could ride out to the train and back to civilization. -

Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (86Th, Kansas

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 481 272 CS 512 497 TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (86th, Kansas City, Missouri, July 30-August 2, 2003) . Media Management & Economics Division. PUB DATE 2003-07-00 NOTE 314p.; For other sections of these proceedings, see CS 512 480-498. PUB TYPE Collected Works Proceedings (021) Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Administration; Administrator Behavior; Curriculum Development; *Economics; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Journalism Education; *Mass Media; *Newspapers; Programming (Broadcast); Supervisors; *Television IDENTIFIERS Cellular Telephones; Digital Technology; Financial Reports; Television News ABSTRACT The Media Management & Economics Division of the proceedings contains the following 11 papers: "Supervisor Leadership Behavior's Effect on Television Newsworker Professionalism" (Natalie Corey); "Applying the Structure-Conduct-Performance Framework in the Media Industry Analysis" (W. Wayne Fu); "The Bigger, the Better? Measuring the Financial Performance of Media Firms" (Jaemin Jung); "Effects of Culture on Cellular Telephone Adoption: The Case of Taiwan" (Kenneth C.C. Yang); "Has Lead-In Lost Its Punch?: A Comparison of Prime Time Ratings Inheritance Effects Between 1992 and 2002" (Walter S. McDowell and Steven J. Dick); "Strange Bedfellows: The Diffusion of Convergence in Four News Organizations" (Jane B. Singer); "Audience Concentration in the Media: Cross-Media Comparisons and the Introduction of the Uncertainty Measure" (Jungsu Yim); "A 20th Century Phenomenon: Employee-Owned Dailies Rare, and 71% Fail" (Fred Fedler); "Teaching Media Management in the 21st Century: What Curricula Is Needed?" (Kenneth D. Loomis. and Alan B. Albarran); "An Examination of How Horizontal Integration of Daily Newspapers Affects Prices and Competition" (Hugh J. -

801 K Street NW Washington, D.C. 20001

801 K Street NW Washington, D.C. 20001 www.DCHistory.org SPECIAL COLLECTIONS FINDING AID Title: MS 0846, Clarence Hewes Scrapbook Collection, 1906-1962 Processor: David G. Wood Processed Date: April 2016 [Finding Aid last updated April 12, 2016] Clarence Bussey Hewes was born in Jeanerette, Louisiana, on February 1, 1890, to Harry Bartram and Nellie Bussey Hewes. The family also included Clarence’s two sisters, Amy (later Mrs. Robert Edmund Floweree) and Florence (later Mrs. Arthur Breese Griswold). Harry Hewes, a native of Texas, had come to Louisiana in the 1880s and made a fortune developing the local lumber industry. According to articles found in the scrapbooks, the Hewes were descended from a North Carolina family that included Joseph Hewes of Edenton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence who organized the first American naval force. Hewes attended the Dixon Academy in Covington, Louisiana; the University of Virginia (LL.B., 1914); and Tulane University (Bachelor of Laws in Civil Law, 1915). He came to Washington, D.C., in 1916, and in 1917-1918 served as private secretary to the Honorable Charles C. McChord, one of the commissioners heading the Interstate Commerce Commission. On February 10, 1919, he began a career at the Department of State, assigned as Third Secretary at the U.S. Legation in Panama. He then served at the U.S. embassies or legations in the Netherlands (1920-1922), and Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Guatemala (1922-1924), before being assigned as First Secretary at the embassy in Peking, China. He remained in China until 1930 when he was designated First Secretary at the embassy in Berlin, Germany. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications “MOB SISTERS”: WOMEN REPORTING ON CRIME IN PROHIBITION-ERA CHICAGO A Dissertation in Mass Communications by Beth Fantaskey Kaszuba © 2013 Beth Fantaskey Kaszuba Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2013 The dissertation of Beth Fantaskey Kaszuba was reviewed and approved* by the following: Ford Risley Head, Department of Journalism Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Ann Marie Major Associate Professor of Communications Russell Frank Associate Professor of Communications Marie Hardin Associate Dean for Undergraduate and Graduate Education *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the work of five women who were employed by the Chicago Tribune as general assignment reporters during the 1920s, and whose unique way of covering the city’s epidemic of crime – with sarcastic humor, a cynical viewpoint and slang-infused prose – merits the creation of a new “category” of female reporter, dubbed here the “mob sister.” Histories of American media generally place women reporters who worked at newspapers prior to World War II into narrowly proscribed roles, leading to a widespread assumption that women were only allowed to cover topics such as fashion, society, and news of interest to homemakers. In addition, most histories tell us that those women who did make the front pages worked either as “stunt girls,” performing daring feats and then writing about their exploits to shock or titillate readers, or as “sob sisters,” covering trials in maudlin prose intended to bring readers to tears. However, a significant number of women broke those barriers during the Prohibition era, especially in Chicago, where the Tribune, in particular, gave women journalists wide latitude to pursue beats traditionally considered more suitable for men in that period. -

082321 Knoxville Focus

PAGE APB The Knoxville Focus August 23, 2021 August 23, 2021 The Kwww.knoxfocus.comnoxvil le PAGE A1 PAID FOR BY THE COMMITTEE TO ELECT NICK CIPARRO - CITY COUNCIL DISTRICT 3. NICK CIPARRO, TREASURER OCUS FREETake One! www.knoxfocus.com F August 23, 2021 Phone: 865-686-9970 | PO Box 18377, Knoxville, TN 37928 | Located at 4109 Central Avenue Pike, Knoxville, Tennessee 37912 Pellissippi State opens Bill Haslam Center for Math and Science By Ken Lay Haslam were on hand for said that the new facility with BarberMcMurry Archi- Former Tennessee A rainy day couldn’t throw the festivities. will enhance the campus’s tects in thinking about what Governor and a damper on the excitement The community college math and science pro- this space might look like, Knoxville City at Pellissippi State Commu- welcomes students back grams and enable the col- not about only for teach- Mayor Bill nity College’s Hardin Valley this week and its math and lege to offer new classes ing and learning inside the Haslam speaks campus Tuesday. science students now have for its students. classroom, but for the kind at the dedication The inclement weather a new state-of-the art facili- “We made a strategic of collaboration that is nec- ceremony at the forced the school’s admin- ty to pursue their academic decision that if we’re going essary outside the class- opening of the Bill istration to shuffle to make endeavors. to teach science, mathe- room for our students.” Haslam Center changes but Pellissippi The building officially matics and teacher edu- Pellissippi State alum- for Math and State dedicated the Bill opened with a ribbon cut- cation, as well as have the nus Carlos Gonzalez was Science Tuesday Haslam Center for Math ting on Tuesday. -

Alicia Patterson

--------------- ----- ---- ---- ra Alicia Patterson Presenter – Geri Solomon Assistant Dean of Special Collections Hofstra University !l.lilrBER tol. ,~:r.1: - lih~ _.... -k"llblil • • JI. • ..... Illalliiii,il~ · •a.;11,T, NU1H1 • !""'""''-""-.. ;..-;;:..,l"Mb l!lole!l!!!!I - ..c.:;;;.;.;.:.,,'ii-,.ji '" -~- ~IY!!o ra: .-.-..... .---,....... II" •11 ' .. .....Hilk.Ill.I nt:'~Mlliiat~ lao==T=--_,, ' r,i..i " ■-~ ~b ~~":..~:•-~ ~~~.~-·~--- . - · --- - ·1111!1111i ._..,_ I !?,Ll'ffUilnt., Alicia Patterson was born in Chicago on October 15, 1906. Her great-great- grandfather James Patrick set up a small weekly, the Tuscarawas Chronicle, in New Philadelphia, Tuscarawas County, Ohio in 1819. Her grandfather, father and aunt were also in the newspaper business. It seemed inevitable that she would be in the business as well! Alicia’s father was Joseph Medill Patterson. He started The Daily News. His father, Robert W. Patterson, Jr. was a journalist at the Chicago Tribune. Her mother was Alice Higinbotham Patterson. Alice’s father was the president of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and the financial executive for Marshall Field & Co. Alicia’s aunt was known as “Cissy” Patterson and was the editor and publisher of the Washington Times- Herald from 1930 until her death in 1948. Alicia, was the middle daughter, but she behaved as a substitute “son” for Joseph Patterson. She learned to fly a plane, hunted big game and was a risk-seeker and adventurer. Alicia had a love of flying, and she became a Transport Pilot in 1931. She held the Woman’s Aviation Record from New York to Philadelphia. Alicia worked for her father at the Daily News, first in the promotions department then as a reporter.