Czechoslovak and Soviet State Security Against the West Before 1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Reimagining

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Reimagining Everyday Life in the GDR Post-Ostalgia in Contemporary German Films and Museums Kreibich, Stefanie Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Reimagining Everyday Life in the GDR: Post-Ostalgia in Contemporary German Films and Museums Stefanie Kreibich Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Modern Languages Bangor University, School of Modern Languages and Cultures April 2018 Abstract In the last decade, everyday life in the GDR has undergone a mnemonic reappraisal following the Fortschreibung der Gedenkstättenkonzeption des Bundes in 2008. No longer a source of unreflective nostalgia for reactionaries, it is now being represented as a more nuanced entity that reflects the complexities of socialist society. The black and white narratives that shaped cultural memory of the GDR during the first fifteen years after the Wende have largely been replaced by more complicated tones of grey. -

Works’ (Just Not in Moderation)

Repression ‘Works’ (just not in moderation) Yuri M. Zhukov University of Michigan Abstract Why does government violence deter political challengers in one con- text, but inflame them in the next? This paper argues that repression increases opposition activity at low and moderate levels, but decreases it in the extreme. There is a threshold level of violence, where the op- position becomes unable to recruit new members, and the rebellion unravels – even if the government kills more innocents. We show this result logically, with a mathematical model of coercion, and empir- ically, with micro-level data from Chechnya and a meta-analysis of sub-national conflict dynamics in 156 countries. The data suggest that a threshold exists, but the level of violence needed to reach it varies. Many governments, thankfully, are unable or unwilling to go that far. We explore conditions under which this threshold may be higher or lower, and highlight a fundamental trade-off between reducing gov- ernment violence and preserving civil liberties. Keywords: repression, political violence, mass killing, conflict, meta-analysis, threshold effect Word count: 11,869 DRAFT This version: November, 2018 1 Repression is violence that governments use to stay in power. When confronting behavioral challenges to their authority, governments often respond by threatening, detaining and killing suspected dissidents and rebels. The coercive purpose of these actions is to compel challengers to stop their fight, and to deter others from joining it. The intensity of repres- sion can vary greatly. To reestablish control in Chechnya after 1999, for example, the Russian government used a range of methods, from targeted killings to shelling and indiscriminate sweeps. -

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation J. MICHAEL WALLER "They write I'm the mafia's godfather. It was Vladimir Ilich Lenin who was the real organizer of the mafia and who set up the criminal state." -Otari Kvantrishvili, Moscow organized crime leader.l "Criminals Nave already conquered the heights of the state-with the chief of the KGB as head of a mafia group." -Former KGB Maj. Gen. Oleg Kalugin.2 Introduction As the United States and Russia launch a Great Crusade against organized crime, questions emerge not only about the nature of joint cooperation, but about the nature of organized crime itself. In addition to narcotics trafficking, financial fraud and racketecring, Russian organized crime poses an even greater danger: the theft and t:rafficking of weapons of mass destruction. To date, most of the discussion of organized crime based in Russia and other former Soviet republics has emphasized the need to combat conven- tional-style gangsters and high-tech terrorists. These forms of criminals are a pressing danger in and of themselves, but the problem is far more profound. Organized crime-and the rarnpant corruption that helps it flourish-presents a threat not only to the security of reforms in Russia, but to the United States as well. The need for cooperation is real. The question is, Who is there in Russia that the United States can find as an effective partner? "Superpower of Crime" One of the greatest mistakes the West can make in working with former Soviet republics to fight organized crime is to fall into the trap of mirror- imaging. -

Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010

Description of document: US Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010 Requested date: 07-August-2010 Released date: 15-August-2010 Posted date: 23-August-2010 Title of document Impersonal Names Index Listing Source of document: Commander U.S. Army Intelligence & Security Command Freedom of Information/Privacy Office ATTN: IAMG-C-FOI 4552 Pike Road Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755-5995 Fax: (301) 677-2956 Note: The IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents INSCOM investigative files that are not titled with the name of a person. Each item in the IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents a file in the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository. You can ask for a copy of the file by contacting INSCOM. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. -

Dismantling the Czechoslovak Secret Police

Dismantling the Czechoslovak Secret Police JAROSLAV BASTA The purpose of this talk is to share a small part of the Czechoslovak (now just Czech) experience with the process of the transformation of its secret services. 1 hope that my words will be understood as a reflection-I am not trying to teach, but to share our experience during the long process in Czechoslovakia. You know, it is always better to learri from the experience of others than from your own. The main differences between Russia and the Czech Republic, in this case, are mainly the period or stage of evolution. What 1 heard yesterday at this conference, reminds me of the discussions we had in Czechoslovakia back in 1990. At this point in time we were trying to solve a key problem-what to do with the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the security organization amid the process of social and national democratization. We went through several stages of decision-making. At first, we thought that we could just reform the services by reviewing the members of the State Security Organízation (StB), keeping the less discredited ones; by eliminating the department specialized in the so-called "fighting against internal enemies;" and. by continuing to use, under strict parliamentary control, the Secret Intelligence Service and technical support departments comprised of new people. Almost the lame concept or methodology was used in Poland and Hungary, where the whole process of transition from totalitarism to democracy was slower and more gradual. It is only symbolic that this concept was rejected early after the first liberal elections in 1990. -

Eastern Europe in 1968 Kevin Mcdermott · Matthew Stibbe Editors Eastern Europe in 1968

Eastern Europe in 1968 Kevin McDermott · Matthew Stibbe Editors Eastern Europe in 1968 Responses to the Prague Spring and Warsaw Pact Invasion Editors Kevin McDermott Matthew Stibbe Sheffeld Hallam University Sheffeld Hallam University Sheffeld, UK Sheffeld, UK ISBN 978-3-319-77068-0 ISBN 978-3-319-77069-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77069-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018934657 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affliations. -

Diario Militar”) V

Amicus Curiae Submission in the Case of Gudiel Álvarez y Otros (“Diario Militar”) v. Guatemala A Submission to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights from The Open Society Justice Initiative, La Asociación Pro-Derechos Humanos, and La Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos Humanos, A.C. May 10, 2012 Case No. 12.590 Caso Gudiel Álvarez y Otros v. Guatemala (“Diario Militar” Case) Amicus Curiae Brief of The Open Society Justice Initiative, La Asociación Pro-Derechos Humanos, and La Comisión Mexicana De Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos Humanos, A.C. I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. THE RIGHT TO TRUTH IN INTERNATIONAL LAW ................................................................................... 3 A. THE RIGHT TO TRUTH REGARDING GROSS HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS OR SERIOUS VIOLATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW ................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Recognition and Origins of the Right to Truth ................................................................................................. 3 2. Scope and Content of the Right to Truth .......................................................................................................... 5 3. Relationship with the Right to Information and Other Rights .......................................................................... 6 4. The Right -

NKVD/KGB Activities and Its Cooperation with Other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945-1989, II

NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945-1989, II. INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE NOveMbeR 19-21, 2008, PRagUE Under the auspices of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security of the Senate of the Parliament of the Czech Republic and in cooperation with the Institute of National Remembrance and the Institute of Historical Studies of the Slovak Academy of Sciences Index INTRODUCTION . 4 PROGRAM . 6 ABSTRacTS . 16 PaneL 1 . 16 PaneL 2 . 24 PaneL 3 . 38 PaneL 4 . 50 PaneL 5 . 58 3 Introduction The activity of Soviet security units, particularly State Security known throughout the world under the acronym of KGB, remains one of the most important subjects for 20th century research in Central and Eastern Europe. The functioning and operation of this apparatus, which surpassed the activities of the police in countries with democratic systems severalfold, had a significant and direct influence on the shape of the totalitarian framework; the actions of party members of the Communist nomenclature; and the form, methods and extent of the repression of “class enemies” and, in the final instance, upon innocent representatives of various socio- political groups. Additionally, the supranational Cheka elite, created in line with Communist ideology, were not only supposed to take part in the repression of political opponents, but also in the casting of a new man (being), carrying out the will of the superior nomenclature. That was one reason why selection of members of the secret politi- cal police was so strict. 4 International cooperation is needed in order to reconstruct and present the breadth, extent and influence of Soviet security units in our key region. -

HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS of SOVIET Terroi\

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. I --' . ' J ,j HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS OF SOVIET TERROi\ .. HEARINGS BEFORE THE SUBOOMMITTEE ON SECURITY AND TERRORISM OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED ST.A.g;ES;~'SEN ATE NINETY-SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON THE HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS OF SOVIET TERRORISM JUNE 11 AND 1~, 1981 Serial No.. J-97-40 rinted for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary . ~.. ~. ~ A\!?IJ.ISIJl1 ~O b'. ~~~g "1?'r.<f~~ ~l~&V U.R. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1981 U.S. Department ':.~ Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permissic;m to reproduce this '*ll'yr/gJorbJ material has been CONTENTS .::lrante~i,. • . l-'ubllC Domain UTIltea~tates Senate OPENING STATEMENTS Page to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Denton, Chairman Jeremiah ......................................................................................... 1, 29 Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the 00j5) I i~ owner. CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF WITNESSES JUNE 11, 1981 COMMI'ITEE ON THE JUDICIARY Billington, James H., director, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars ......................................................................................................................... 4 STROM THU'lMOND;1South Carolina, Chairman Biography .................................................................................................................. 27 CHARLES McC. MATHIAS, JR., Maryland JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware PAUL LAXALT Nevada EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JUNE 12, 1981 ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia. Possony, Stefan T., senior fellow (emeritus), Hoover Institution, Stanford Uni- ROBERT DOLE Kansas HOWARD M. -

Rudolf Slansky: His Trials and Trial

COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER #50 Rudolf Slansky: His Trials and Trial By Igor Lukes THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. The CWIHP Working Paper Series is designed to provide a speedy publications outlet for historians associated with the project who have gained access to newly-available archives and sources and would like to share their results. -

The Stasi at Home and Abroad the Stasi at Home and Abroad Domestic Order and Foreign Intelligence

Bulletin of the GHI | Supplement 9 the GHI | Supplement of Bulletin Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Supplement 9 (2014) The Stasi at Home and Abroad Stasi The The Stasi at Home and Abroad Domestic Order and Foreign Intelligence Edited by Uwe Spiekermann 1607 NEW HAMPSHIRE AVE NW WWW.GHI-DC.ORG WASHINGTON DC 20009 USA [email protected] Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Washington DC Editor: Richard F. Wetzell Supplement 9 Supplement Editor: Patricia C. Sutcliffe The Bulletin appears twice and the Supplement usually once a year; all are available free of charge and online at our website www.ghi-dc.org. To sign up for a subscription or to report an address change, please contact Ms. Susanne Fabricius at [email protected]. For general inquiries, please send an e-mail to [email protected]. German Historical Institute 1607 New Hampshire Ave NW Washington DC 20009-2562 Phone: (202) 387-3377 Fax: (202) 483-3430 Disclaimer: The views and conclusions presented in the papers published here are the authors’ own and do not necessarily represent the position of the German Historical Institute. © German Historical Institute 2014 All rights reserved ISSN 1048-9134 Cover: People storming the headquarters of the Ministry for National Security in Berlin-Lichtenfelde on January 15, 1990, to prevent any further destruction of the Stasi fi les then in progress. The poster on the wall forms an acrostic poem of the word Stasi, characterizing the activities of the organization as Schlagen (hitting), Treten (kicking), Abhören (monitoring), -

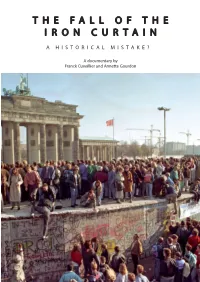

Page 1 1 T H E F a L L O F T H E I R O N C U R T a I N

THE FALL OF THE IRON CURTAIN A HISTORICAL MISTAKE? A documentary by Franck Cuveillier and Annette Gourdon 1 PRODUCER’S NOTE ovember 2019 will mark the 30th She is fluent in Russian and in German. anniversary of the fall of the Berlin For this project, they decided to focus on Wall and of the collapse of communist N four countries, all of which suffered from regimes throughout Eastern Europe. Yet, the Iron Curtain and underwent popular new migration phenomenons today bring uprisings that were quelled by Russia: East Europe to question its borders once again. Germany, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and For 37 years (1952-1989), millions of Poland. Most of the shooting will take place European citizens lived behind an actual in these countries, especially along the line of Iron Curtain, made of over 5,000 miles the former Iron Curtain. Additionally, several of walls and fences preventing them from interviews will be led in Paris and in Moscow. crossing to the West without their country’s formal authorization. It seems interesting As we only have so much time to see this to us to shed light on this specific period in production through, we have decided to European history, at a time when European approach two TV channels, in Poland and nations are reconsidering the 1985 Schengen in Belgium, which already own archives Agreement signed by Western Europe. from that time: TVP and RTBF, respectively. A team from the latter, for example, filmed The goal of this film is to tell the story of the East Germany, Poland and Russia in 1987, Iron Curtain that sliced Europe in half, with aboard a train traveling from Brussels to distance and perspective.