Re-Evaluating the Neolithic: the Impact and the Consolidation of Farming Practices in the Cantabrian Region (Northern Spain)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-1 Basauri "F" - Basauri "D" Arrankudiaga "B" - Basauri "C" FRONTOIA: Orozko "E" - Arrigorriaga "B" Descanso: - Basauri "E" 03 -URRIA-OCTUBRE

IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-1 Basauri "F" - Basauri "D" Arrankudiaga "B" - Basauri "C" FRONTOIA: Orozko "E" - Arrigorriaga "B" Descanso: - Basauri "E" 03 -URRIA-OCTUBRE IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-2 Basauri "C" - Orozko "E" Basauri "D" - Arrankudiaga "B" FRONTOIA: Basauri "E" - Basauri "F" Descanso: - Arrigorriaga "B" 10 -URRIA-OCTUBRE IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-3 Arrankudiaga "B" - Basauri "E" Orozko "E" - Basauri "D" FRONTOIA: Arrigorriaga "B" - Basauri "C" Descanso: - Basauri "F" 17 -URRIA-OCTUBRE IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-4 Basauri "D" - Arrigorriaga "B" Basauri "E" - Orozko "E" FRONTOIA: Basauri "F" - Arrankudiaga "B" Descanso: - Basauri "C" 24 -URRIA-OCTUBRE IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-5 Orozko "E" - Basauri "F" Arrigorriaga "B" - Basauri "E" FRONTOIA: Basauri "C" - Basauri "D" Descanso: - Arrankudiaga "B" 31 -URRIA-OCTUBRE IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-6 10 Basauri "E" - Basauri "C" Basauri "F" - Arrigorriaga "B" FRONTOIA: Arrankudiaga "B" - Orozko "E" Descanso: - Basauri "D" 07- AZAROA-NOVIEMBRE IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-7 Arrigorriaga "B" - Arrankudiaga "B" Basauri "C" - Basauri "F" FRONTOIA: Basauri "D" - Basauri "E" Descanso: - Orozko "E" 14- AZAROA-NOVIEMBRE IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-1 IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-6 Zornotza "B" - Zornotza "C" FRONTOIA: Orozko "D" - Basauri "B" FRONTOIA: Descanso: - Orozko "C" 03 -URRIA-OCTUBRE 07- AZAROA-NOVIEMBRE IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-2 IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-7 Zornotza "C" - Orozko "D" FRONTOIA: Orozko "C" - Zornotza "B" FRONTOIA: Descanso: - Basauri "B" 09 -URRIA-OCTUBRE 13- AZAROA-NOVIEMBRE IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-3 IHARDUNAL-JORNADA-8 Zornotza "C" - Orozko "C" FRONTOIA: Zornotza "B" -

Relationship Between Shell - Midden S and Neolithic Paleoshorelines with Examples from Brazil and Japan *

Rev. do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, São Paulo, 3: 55-65,1993. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SHELL - MIDDEN S AND NEOLITHIC PALEOSHORELINES WITH EXAMPLES FROM BRAZIL AND JAPAN * Kenitiro Suguio** SUGUIO, K. Relationship between shell-middens and neolithic paleoshorelines with examples from Brazil and Japan. Rev. do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, Sâo Paulo, 3: 55-65, 1993. RESUMO: Este trabalho trata de aspectos gerais dos sambaquis da costa sudeste brasileira, particularmente da planície Cananéia-Iguape (SP), enfatizando a sua utilidade na reconstrução de paleolinhas de costa a partir do Holoceno médio. Algumas peculiaridades dos sambaquis da planície de Kanto (Japão), aproximadamente contemporâneos aos brasileiros, são também apresentadas. Em ambos os casos, para a identificação da posição de paleonível relativo do mar, as seguintes informações devem ser obtidas de cada sambaqui. (a) distância da atual borda marinha ou lagunar; (b) natureza e idade do substrato; (c) altitude do substrato acima do nível de maré alta; (d) épocas de ocupação e de abandono do sítio; (e) valores de Ô13C (PDB)dos carbonatos das conchas; (f) espécies predominantes de moluscos e (g) tamanho do sambaqui. UNITERMOS: Paleolinha de costa neolítica - Transgressão Santos - Transgressão Jomon - Holoceno, Brasil, Japão. Generalities hundreds of giant shell-middens (Fig. 2) are known. Their usefulness for sea-level height/ Artificial accumulations made up of shells of shoreline reconstruction has been not very clearly brackish water and marine organisms are very expressed in many papers, but this problem was commonly found in coastal regions around the more precisely emphasized in Brazil only in the world, as in Natal (South Africa), southern recent years (Martin & Suguio, 1976; Martin et Madagascar, eastern Australia (particularly the al., 1981/1982; 1986; Suguio, 1990 and Suguio “New England” coast of New South Wales), etal., 1992). -

Pais Vasco 2018

The País Vasco Maribel’s Guide to the Spanish Basque Country © Maribel’s Guides for the Sophisticated Traveler ™ August 2018 [email protected] Maribel’s Guides © Page !1 INDEX Planning Your Trip - Page 3 Navarra-Navarre - Page 77 Must Sees in the País Vasco - Page 6 • Dining in Navarra • Wine Touring in Navarra Lodging in the País Vasco - Page 7 The Urdaibai Biosphere Reserve - Page 84 Festivals in the País Vasco - Page 9 • Staying in the Urdaibai Visiting a Txakoli Vineyard - Page 12 • Festivals in the Urdaibai Basque Cider Country - Page 15 Gernika-Lomo - Page 93 San Sebastián-Donostia - Page 17 • Dining in Gernika • Exploring Donostia on your own • Excursions from Gernika • City Tours • The Eastern Coastal Drive • San Sebastián’s Beaches • Inland from Lekeitio • Cooking Schools and Classes • Your Western Coastal Excursion • Donostia’s Markets Bilbao - Page 108 • Sociedad Gastronómica • Sightseeing • Performing Arts • Pintxos Hopping • Doing The “Txikiteo” or “Poteo” • Dining In Bilbao • Dining in San Sebastián • Dining Outside Of Bilbao • Dining on Mondays in Donostia • Shopping Lodging in San Sebastián - Page 51 • Staying in Bilbao • On La Concha Beach • Staying outside Bilbao • Near La Concha Beach Excursions from Bilbao - Page 132 • In the Parte Vieja • A pretty drive inland to Elorrio & Axpe-Atxondo • In the heart of Donostia • Dining in the countryside • Near Zurriola Beach • To the beach • Near Ondarreta Beach • The Switzerland of the País Vasco • Renting an apartment in San Sebastián Vitoria-Gasteiz - Page 135 Coastal -

Adaptación Antenas Colectivas De La

Últimas semanas para realizar la adaptación en Vizcaya CUENTA ATRÁS PARA FINALIZAR LA ADAPTACIÓN DE LAS ANTENAS COLECTIVAS DE TDT EN 112 MUNICIPIOS El próximo 11 de febrero algunos canales de TDT dejarán de emitir en sus antiguas frecuencias en 7 municipios, mientras que en el resto de la provincia cesarán las emisiones el 3 de marzo. Solo en el *51% de los edificios comunitarios de la provincia se han realizado ya las adaptaciones necesarias para seguir disfrutando de la oferta completa de TDT a partir de estas fechas Los administradores de fincas o presidentes de comunidades de propietarios deben contactar lo antes posible con una empresa instaladora registrada Además, a partir de la fecha de cese de emisiones de cada municipio, todos los ciudadanos de Vizcaya deberán resintonizar el televisor con su mando a distancia Toda la información sobre el cambio de frecuencias de la TDT está disponible en la página web www.televisiondigital.es y a través de los números de atención telefónica 901 20 10 04 y 91 088 98 79 Vitoria-Gasteiz, 21 de enero de 2020. Cuenta atrás para el cambio de frecuencias de la Televisión Digital Terrestre (TDT) en Vizcaya. A partir del próximo 11 de febrero, algunos canales estatales y autonómicos dejarán de emitir a través de sus antiguas frecuencias en Amoroto, Berriatua, Ea, Ispaster, Lekeitio, Mendexa y Ondarroa, mientras que en otros 105 municipios del resto de la provincia, incluida la capital, lo harán el 3 de marzo. Solo en el *51% de los aproximadamente 27.300 edificios comunitarios de tamaño mediano y grande de la provincia -que deben adaptar su instalación de antena colectiva- se ha realizado esta adaptación. -

The Rock Art of Madjedbebe (Malakunanja II)

5 The rock art of Madjedbebe (Malakunanja II) Sally K. May, Paul S.C. Taçon, Duncan Wright, Melissa Marshall, Joakim Goldhahn and Inés Domingo Sanz Introduction The western Arnhem Land site of Madjedbebe – a site hitherto erroneously named Malakunanja II in scientific and popular literature but identified as Madjedbebe by senior Mirarr Traditional Owners – is widely recognised as one of Australia’s oldest dated human occupation sites (Roberts et al. 1990a:153, 1998; Allen and O’Connell 2014; Clarkson et al. 2017). Yet little is known of its extensive body of rock art. The comparative lack of interest in rock art by many archaeologists in Australia during the 1960s into the early 1990s meant that rock art was often overlooked or used simply to illustrate the ‘real’ archaeology of, for example, stone artefact studies. As Hays-Gilpen (2004:1) suggests, rock art was viewed as ‘intractable to scientific research, especially under the science-focused “new archaeology” and “processual archaeology” paradigms of the 1960s through the early 1980s’. Today, things have changed somewhat, and it is no longer essential to justify why rock art has relevance to wider archaeological studies. That said, archaeologists continued to struggle to connect the archaeological record above and below ground at sites such as Madjedbebe. For instance, at this site, Roberts et al. (1990a:153) recovered more than 1500 artefacts from the lowest occupation levels, including ‘silcrete flakes, pieces of dolerite and ground haematite, red and yellow ochres, a grindstone and a large number of amorphous artefacts made of quartzite and white quartz’. The presence of ground haematite and ochres in the lowest deposits certainly confirms the use of pigment by the early, Pleistocene inhabitants of this site. -

Recent Advances in the Prehistoric Archaeology of Formosa* by Kwang-Chih Chang and Minze Stuiver

RECENT ADVANCES IN THE PREHISTORIC ARCHAEOLOGY OF FORMOSA* BY KWANG-CHIH CHANG AND MINZE STUIVER DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND PEABODY MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, AND DEPARTMENTS OF GEOLOGY AND BIOLOGY AND RADIOCARBON LABORATORY, YALE UNIVERSITY Communicated by Irving Rouse, January 26, 1966 The importance of Formosa (Taiwan) as a first steppingstone for the movement of peoples and cultures from mainland Asia into the Pacific islands has long been recognized. The past 70 years have witnessed considerable high-quality study of both the island's archaeology' and its ethnology,2 but it has become increasingly evident that to explore fully Formosa's position in the culture history of the Far East it is imperative also to enlist the disciplines of linguistics, ethnobiology, and the environmental sciences.3 It is with this aim that preliminary and exploratory in- vestigations were carried out in Formosa under the auspices of the Department of Anthropology of Yale University, in collaboration with the Departments of Biology at Yale, and of Archaeology-Anthropology and Geology at National Taiwan Uni- versity (Taipei, Taiwan), during 1964-65. As a result of these investigations, pre- historic cultures can now be formulated on the basis of excavated material, and be placed in a firm chronology, grounded on stratigraphic and carbon-14 evidence. This prehistoric chronology, moreover, can be related to environmental changes during the postglacial period, established by geological and palaeobiological data. Comparison of the new information with prehistoric culture histories in the ad- joining areas in Southeast China, the Ryukyus, and Southeast Asia throws light on problems of cultural origins and contacts in the Western Pacific region, and suggests ways in which to utilize Dyen's recent linguistic work,4 as well as current ethnologi- cal research. -

Natural Beauty Spots Paradises to Be Discovered

The Active OUTDOORS Natural Beauty Spots Paradises to be discovered Walking and biking in Basque Country Surfing the waves Basque Coast Geopark Publication date: April 2012 Published by: Basquetour. Basque Tourism Agency for the Basque Department of Industry, Innovation, Commerce and Tourism Produced by: Bell Communication Photographs and texts: Various authors Printed by: MCC Graphics L.D.: VI 000-2011 The partial or total reproduction of the texts, maps and images contained in this publication without the San Sebastián express prior permission of the publisher and the Bilbao authors is strictly prohibited. Vitoria-Gasteiz All of the TOP experiences detailed in TOP in this catalogue are subject to change and EXPE RIEN may be updated. Therefore, we advise you CE to check the website for the most up to date prices before you book your trip. www.basquecountrytourism.net The 24 Active OUT- DOORS 20 28LOCAL NATURE SITES 6 Protected Nature Reserves Your gateway to Paradise 20 Basque Country birding Bird watching with over 300 species 24 Basque Coast Geopark Explore what the world way 6 34 like 60 million years ago ACTIVITIES IN THE BASQUE COUNTRY 28 Surfing Surfing the Basque Country amongst the waves and mountains 34 Walking Walking the Basque Country Cultural Landscape Legacy 42 42 Biking Enjoy the Basque Country's beautiful bike-rides 48 Unmissable experiences 51 Practical information Gorliz Plentzia Laredo Sopelana THE BASQUE Castro Urdiales Kobaron Getxo ATXURI Pobeña ITSASLUR Muskiz GREENWAY GREENWAY Portugalete ARMAÑÓN Sondika COUNTRY'S MONTES DE HIERRO Gallarta Sestao NATURAL PARK GREENWAY Ranero BILBAO La Aceña-Atxuriaga PROTECTED Traslaviña Balmaseda PARKS AND AP-68 Laudio-Llodio RESERVES Amurrio GORBEIA NATURAL PARK Almost 25% of Basque Country Orduña territory comprises of protected nature areas: VALDEREJO A Biosphere Reserve, nine AP-68 NATURAL PARK Natural Parks, the Basque Lalastra Coast Geopark, more than Angosto three hundred bird species, splendid waves for surfing and Zuñiga Antoñana numerous routes for walking or biking. -

Basques in the Americas from 1492 To1892: a Chronology

Basques in the Americas From 1492 to1892: A Chronology “Spanish Conquistador” by Frederic Remington Stephen T. Bass Most Recent Addendum: May 2010 FOREWORD The Basques have been a successful minority for centuries, keeping their unique culture, physiology and language alive and distinct longer than any other Western European population. In addition, outside of the Basque homeland, their efforts in the development of the New World were instrumental in helping make the U.S., Mexico, Central and South America what they are today. Most history books, however, have generally referred to these early Basque adventurers either as Spanish or French. Rarely was the term “Basque” used to identify these pioneers. Recently, interested scholars have been much more definitive in their descriptions of the origins of these Argonauts. They have identified Basque fishermen, sailors, explorers, soldiers of fortune, settlers, clergymen, frontiersmen and politicians who were involved in the discovery and development of the Americas from before Columbus’ first voyage through colonization and beyond. This also includes generations of men and women of Basque descent born in these new lands. As examples, we now know that the first map to ever show the Americas was drawn by a Basque and that the first Thanksgiving meal shared in what was to become the United States was actually done so by Basques 25 years before the Pilgrims. We also now recognize that many familiar cities and features in the New World were named by early Basques. These facts and others are shared on the following pages in a chronological review of some, but by no means all, of the involvement and accomplishments of Basques in the exploration, development and settlement of the Americas. -

Puente De Isuntza (Lekeitio)

PATRIMONIO HISTÓRICO DE BIZKAIA Puente de Isuntza (Lekeitio) Este esbelto puente de Isuntza, en la muga de los municipios La búsqueda de una mayor luz para facilitar el paso de de Lekeitio y Mendexa, salva el cauce del río Lea muy cerca de embarcaciones elevó, lógicamente, la cota central del arco, su desembocadura y une por carretera las playas de ambas por lo que el puente, en el momento de su construcción, ofrecía localidades, Isuntza y Karraspio. Ocupa, además, un emplazamiento un perfil sensiblemente alomado, como lo recogen algunos estratégico sobre la bocana de la ría, disfrutando de unas muy grabados. En la actualidad, esta característica de la obra original atractivas panorámicas sobre el conjunto de astilleros artesanales, ha quedado enmascarada por una reforma, relativamente situados en ambas márgenes, para la construcción y reparación reciente, que ha elevado las cotas laterales de los tímpanos de barcos con casco de madera. hasta alcanzar una rasante horizontal. La reforma, no obstante, se diferencia perfectamente, ya que los recrecidos se realizaron La obra que podemos observar en la actualidad no es, sin en sillería. Seguramente durante esta misma reforma se intentó embargo, más que la sustituta en el tiempo de otra u otras ampliar ligeramente la capacidad circulatoria del puente anteriores de las que tenemos algunas noticias documentales. recurriendo a levantar un pretil en voladizo sostenido por Concretamente, conocemos la construcción de un puente en mensulones; no es posible asegurar, sin embargo, que el actual este lugar gracias a un documento fechado en 1596 en el que pretil de hormigón pertenezca también a dicha reforma. -

Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1954 Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Mcintire, William Grant, "Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana." (1954). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8099. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8099 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HjEHisroaic smm&ws in coastal Louisiana A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by William Grant MeIntire B. S., Brigham Young University, 195>G June, X9$k UMI Number: DP69477 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI DP69477 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest: ProQuest LLC. -

Dossier WC2020 EUS V1

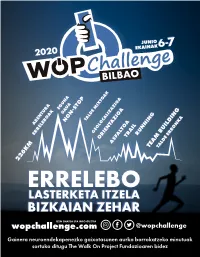

2020 ABENTURA ERRELEBOAK 226KM EGUNA Challenge GAUA NONSTOP BILBAO ERRELEBO EKAINAKJUNIO LASTERKETA ITZELA TALDE MIXTOAK wopchallenge.comBIZKAIAN ZEHAR 6- Gainera neuroendekapenezko gaixotasunen aurka borrokatzeko minutuak GEOLOCALIZAZIOA 7 ORIENTAZIOA ASFALTOA sortuko ditugu The Walk On Project Fundazioaren bidez IZEN EMATEA ETA INFO GUZTIA TRAIL RUNNING TEAM BUILDING TALDE ERRONKA @wopchallenge ALGORTAKO PORTU ARMINTZA ZAHARRA GALDAMES BARRIKA GALLARTA BAKIO ChallengeBILBAO ZORROTZA BILBAO BERMEO MURUETA SODUPE KORTEZUBI ARRIGORRIAGA AULESTI OIZ MENDIA LEGENDA ERMITABARRI Distantzia DIMA Zailtasuna Igoera desnibela MATIENA Jaitsiera desnibela Asfaltoa Trail URKIOLA Mixtoa Etapa Mota Interes puntua 1 ARRIGORRIAGA ChallengeBILBAO BUIA BILBAO ARRIGORRIAGA LA PEÑA 11Km Erraza 194 m GUGGENHEIM BILBAO MUSEOA 142 m 0m 200m 2 ERMITABARRI ChallengeBILBAO ARRIGORRIAGA ERMITABARRI 11,5Km Oso Gogorra 486 m 388 m ARRIGORRIAGA 0m 500m 3 DIMA IGORRE ChallengeBILBAO ERMITABARRI ARÁNZAZU DIMA 9,2Km Gogorra 185 m 221 m ERMITABARRI 0m 300m URKIOLAKO 4 SANTUTEGIA URKIOLA ChallengeBILBAO DIMA URKIOLA BALTZOLAKO KOBAZULOAK 14,8Km INDUSI Oso Gogorra 791 m 191 m DIMA 0m 900m 5 MATIENA ChallengeBILBAO URKIOLA MATIENA MENDIOLA 15,6Km ANBOTO HIRU GURUTZEN Erraza BEGIRATOKIA 206 m 808 m URKIOLA 900m 0m 6 MATIENA OIZ MENDIA OIZ MENDIA ChallengeBILBAO 13,1Km Gogorra GARAI 708 m 46 m MATIENA 800m 0m 7 AULESTI ChallengeBILBAO OIZ MENDIA AULESTI MUNITIBAR 13,8KmMUNITIBAR Erraza 100 m 793 m OIZ MENDIA 800m 0m 8 KORTEZUBI SANTIMAMIÑEKO KOBAZULOA ChallengeBILBAO OMAKO -

Logotipo EUSTAT

EUSKAL ESTATISTIKA ERAKUNDA INSTITUTO VASCO DE ESTADÍSTICA Mirodata from the Estatistic on Marriages 2010 Description of file EUSKAL ESTATISTIKA ERAKUNDA INSTITUTO VASCO DE ESTADÍSTICA Microdata from the Estatistic on Marriages 2010 Description of file CONTENTS 1. Introduction........................................ ¡Error! Marcador no definido. 2. Criteria for selection of variables ........ ¡Error! Marcador no definido. 2.1 Criteria of sensitivity......................¡Error! Marcador no definido. 2.2 Criteria of confidentiality ................¡Error! Marcador no definido. 3. Registry design ................................... ¡Error! Marcador no definido. 4. Description of variables ...................... ¡Error! Marcador no definido. APPENDIX 1............................................ ¡Error! Marcador no definido. Microdata files request sheet 1 EUSKAL ESTATISTIKA ERAKUNDA INSTITUTO VASCO DE ESTADÍSTICA Microdata from the Estatistic on Marriages 2010 Description of file 1. Introduction The statistical operation on Marriages provides information on marriages that affects residents in the Basque Country. The files for the Estatistic on Marriages constitute a product for circulation that targets users with experience in analyzing and processing microdata. This format provides an added value to the user, permitting him or her to carry out data exploitation and analysis that, for obvious limitations, cannot be covered by current circulation in the form of tables, publications and reports. The microdata file corresponding to Marriages is described in this report. The circulation of the Marriages file with data from the first spouse combined with information on the second spouse is carried out on the basis of the usefulness and quality of the information that is going to be included as well as the interest for the user, because it is more beneficial for the person receiving the data to be able to work with them in a combined form.