Financial Sector Integration in Three Regions of Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CBL Annual Report 2019

Central Bank of Liberia Annual Report 2019 Central Bank of Liberia Annual Report January 1 to December 31, 2019 © Central Bank of Liberia 2019 This Annual Report is in line with part XI Section 49 (1) of the Central Bank of Liberia (CBL) Act of 1999. The contents include: (a) report on the Bank’s operations and affairs during the year; and (b) report on the state of the economy, which includes information on the financial sector, the growth of monetary aggregates, financial markets developments, and balance of payments performance. i | P a g e Central Bank of Liberia Annual Report 2019 CENTRAL BANK OF LIBERIA Office of the Executive Governor January 27, 2020 His Excellency Dr. George Manneh Weah PRESIDENT Republic of Liberia Executive Mansion Capitol Hill Monrovia, Liberia Dear President Weah: In accordance with part XI Section 49(1) of the Central Bank of Liberia (CBL) Act of 1999, I have the honor on behalf of the Board of Governors and Management of the Bank to submit, herewith, the Annual Report of the CBL to the Government of Liberia for the period January 1 to December 31, 2019. Please accept, Mr. President, the assurances of my highest esteem. Respectfully yours, J. Aloysius Tarlue, Jr. EXECUTIVE GOVERNOR P.O. BOX 2048, LYNCH & ASHMUN STREETS, MONROVIA, LIBERIA Tel.: (231) 555 960 556 Website: www.cbl.org.lr ii | P a g e Central Bank of Liberia Annual Report 2019 Table of Contents ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................. ix FORWARD ..................................................................................................................................1 The Central Bank of Liberia’s Vision, Mission and Objectives, Function and Autonomy ……4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY………………………………………………..……….………………6 HIGHLIGHTS ......................................................................................................................... -

Covert Capital the Kabila Family’S Secret Investment Bank

Covert Capital The Kabila Family’s Secret Investment Bank May 2019 Cover photo: The Sentry. The Sentry • TheSentry.org Covert Capital: The Kabila Family’s Secret Investment Bank May 2019 Executive Summary It would have been hard to understand the significance of Kwanza Capital just by looking at the company’s headquarters in a commercial garage in Kinshasa’s business district. No sign marked its presence. There was nothing to indicate the company was shuffling over one hundred million dollars through accounts held at a bank linked to the family of Joseph Kabila, who served as president of the Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo) from 2001 to January 2019. Nor would onlookers have had reason to suspect that the company was controlled by members of Congo’s former first family and its close allies. Individuals with knowledge of the company’s activities told The Sentry it maintained a low profile by design and the individuals behind Kwanza Capital apparently sought to minimize their public association with the company. Kwanza Capital, which is now reportedly under liquidation, gained only fleeting public notice as it made unusual maneuvers in the country’s banking sector, but its story is more expansive than the public record would suggest. An investigation by The Sentry into Kwanza Capital’s activities provides a new glimpse into how members of Kabila’s family and inner circle have done business. The Sentry examined the firm’s operations, finances, apparent beneficiaries, business partners, and relationships with government agencies and officials. In addition to maintaining extensive links to a bank run by members of Kabila’s family, Kwanza Capital participated in multiple acquisition attempts in the Congolese banking sector. -

Absa Bank 22

Uganda Bankers’ Association Annual Report 2020 Promoting Partnerships Transforming Banking Uganda Bankers’ Association Annual Report 3 Content About Uganda 6 Bankers' Association UBA Structure and 9 Governance UBA Member 10 Bank CEOs 15 UBA Executive Committee 2020 16 UBA Secretariat Management Team UBA Committee 17 Representatives 2020 Content Message from the 20 UBA Chairman Message from the 40 Executive Director UBA Activities 42 2020 CSR & UBA Member 62 Bank Activities Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 70 December 2020 5 About Uganda Bankers' Association Commercial 25 banks Development 02 Banks Tier 2 & 3 Financial 09 Institutions ganda Bankers’ Association (UBA) is a membership based organization for financial institutions licensed and supervised by Bank of Uganda. Established in 1981, UBA is currently made up of 25 commercial banks, 2 development Banks (Uganda Development Bank and East African Development Bank) and 9 Tier 2 & Tier 3 Financial Institutions (FINCA, Pride Microfinance Limited, Post Bank, Top Finance , Yako Microfinance, UGAFODE, UEFC, Brac Uganda Bank and Mercantile Credit Bank). 6 • Promote and represent the interests of the The UBA’s member banks, • Develop and maintain a code of ethics and best banking practices among its mandate membership. • Encourage & undertake high quality policy is to; development initiatives and research on the banking sector, including trends, key issues & drivers impacting on or influencing the industry and national development processes therein through partnerships in banking & finance, in collaboration with other agencies (local, regional, international including academia) and research networks to generate new and original policy insights. • Develop and deliver advocacy strategies to influence relevant stakeholders and achieve policy changes at industry and national level. -

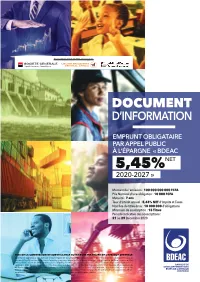

Document Dinformation BDEAC OK OK

Consortium Chef de File, Arrangeurs DOCUMENT D’INFORMATION EMPRUNT OBLIGATAIRE PAR APPEL PUBLIC À L’ÉPARGNE « BDEAC 5,45%NET 2020-2027 » Montant de l’émission : 100 000 000 000 FCFA Prix Nominal d’une obligation : 10 000 FCFA Maturité : 7 ans Taux d’intérêt annuel : 5,45% NET d’Impôts et Taxes Nombre de titres émis : 10 000 000 d’obligations Minimum de souscription : 15 Titres Période indicative des souscriptions : 21 au 29 Décembre 2020 VISA DE LA COMMISSION DE SURVEILLANCE DU MARCHÉ FINANCIER DE L’AFRIQUE CENTRALE La présente opération a été visée par la Commission de Surveillance du Marché Financier de l’Afrique Centrale (COSUMAF) sous le numéro APE---/20 conformément aux dispositions régissant l’appel public à l’épargne sur le Marché Financier Régional, notamment les articles 90 et suivants de l’Acte Uniforme sur le Droit des Sociétés Commerciales et du GIE, 12, alinéa (iv) du Règlement n°06/03 du 12 novembre 2003 portant Organisation, Fonctionnement et Surveillance du Marché Financier de l’Afrique Centrale, 25 et suivants du Règlement Général de la COSUMAF, 1 alinéa (1) de l’Instruction n°2006-01 du 3 mars 2006 relative au document d’information exigé dans le cadre d’un appel public à l’épargne. Le visa de la Commission ne porte pas sur l’opportunité de l’opération envisagée, mais atteste simplement que la COSUMAF a vérifié la pertinence et la cohérence de l’information publiée. I. Sommaire I. SOMMAIRE 02 II. CONDITIONS DE DIFFUSION DU PRESENT DOCUMENT D’INFORMATION 03 III. SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS 05 IV. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

Licensed Commercial Banks As at July 01, 2020

LICENSED COMMERCIAL BANKS AS AT JULY 01, 2020 S/N NAME ADDRESS OF PHONE FAX SWIFT CODE E-MAIL AND WEBSITE HEADQUARTERS 1. ABC Capital Bank Plot 4 Pilkington Road, +256-414-345- +256-414-258- ABCFUGKA [email protected] Uganda Limited Colline House – Kampala 200 310 P.O. BOX 21091 Kampala [email protected] +256-200-516- 600 https://www.abccapitalbank.co.ug/ 2. Absa Bank Uganda Plot 16 Kampala Road, +256-312-218- +256-312-218- BARCUGKX [email protected] Limited P.O. Box 2971, Kampala, 348 393 Uganda +256-312-218- https://www.absa.co.ug/ 300/317 +256-417-122- 408 3. Afriland First Bank - - - - https://www.afrilandfirstgroup.com/ Uganda Limited 4. Bank of Africa Plot 45, Jinja Road. +256-414-302- +256-414-230- AFRIUGKA [email protected] Uganda Limited P.O. Box 2750, Kampala. 001 902 [email protected] +256-414-302- 111 https://boauganda.com/ 5. Bank of Baroda 18, Kampala Road, +256-414-233- +256-414-230- BARBUGKA Uganda Limited Kampala, Uganda. 680 781 [email protected] P.O. Box 7197, Kampala +256-414-345- https://www.bankofbaroda.ug/ 196 6. Bank of India Picfare House, Plot +256 200 422 +256 414 341 BKIDUGKA Uganda Limited No.37,(Next to NWSC 223 880 [email protected] Head Offices) Jinja Road, Kampala + 256 200 422 https://www.boiuganda.co.ug P.O. Box 7332, Kampala, 224 Uganda + 256 313 400 S/N NAME ADDRESS OF PHONE FAX SWIFT CODE E-MAIL AND WEBSITE HEADQUARTERS 437 7. Cairo International Greenland Towers, Plot +256 (0) 414 +256 (0) 414 CAIEUGKA Bank Limited 30 Kampala Road, 230 132/6/7 230 130 [email protected] Kampala P.O.Box 7052 Kampala, +256 (0) 417 Uganda 230 105 https://www.cib.co.ug/ +256 (0) 414 230 141 8. -

Table of Contents

Table of contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY LIST OF TABLES 9 1.1 The Operating Environment 2.1 Developments in Global Output 1.2 The Bank’s Operations and Activities 2.2 Africa: Real GDP Growth 1.3 Development Impact 2.3 Africa: Inflation 2.4 Reserve Position of African Countries 2.5 Africa: Exchange Rate Developments 2 THE OPERATING ENVIRONMENT 2.6 Commodity Prices 2.1 The Global Economic Environment 15 2.7 Real Commodity Prices 2.2 The African Economic Environment 2.8 Africa: Merchandise Trade 2.9 Intra‑African Trade 3. OPERATIONS & ACTIVITIES 3.1 Afreximbank Distribution of Loan Approvals and 51 3.1 Operations Outstandings by Type of Product/Programme 3.2 Activities 3.2 Afreximbank Distribution of Loan Approvals and Outstandings by Sector 3.3 Afreximbank Distribution of Loan Approvals and 4. TRADE DEVELOPMENT IMPACT Outstandings by Type of Beneficiary Institution 91 OF THE BANK’S OPERATIONS 3.4 Afreximbank Distribution of Loan Approvals and AND ACTIVITIES Outstandings by Trade Direction 4.1 Intra‑African Trade 4.2 Industrialization and LIST OF FIGURES Export Development 2.1: Global Output and Inflation 4.3 Trade‑Enabling Infrastructure 2.2: Average GDP Growth of African Net Oil 4.4 Trade Finance Leadership Exporters and Importers 4.5 Trade Development 2.3: Africa: Output by Region Impact Assessments 2.4: Africa: Inflation by Region 2.5: Trends in Africa’s Merchandise Trade 5. MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS OF THE FINANCIAL YEAR 2.6: Trends in Intra‑African Merchandise Trade 105 ENDED 31 DECEMBER, 2017 3.1: Afreximbank Facility Approvals 3.2: Afreximbank Credit Outstanding 5.1 Introduction 3.3: Afreximbank: Distribution of Outstanding Loans, by 5.2 Statement of Comprehensive Income Type of Product/Programme 5.3 Statement of Financial Position 3.4: Afreximbank Distribution of Loan Approvals by Sector 3.5: Afreximbank Number and Average Size of 6. -

The Bank Scene Newsletter of the Uganda Institute of Banking and Financial Services

The Bank Scene Newsletter of the Uganda Institute of Banking and Financial Services October 2019 BANK OF UGANDA MONETARY POLICY Editorial STATEMENT FOR OCTOBER 2019. Dear our esteemed readers, Here is the October issue of the Bank Scene. We appreciate all our Members and Stakeholders for Participating in the 20th Edition of the Annual Bankers’ Sports Gala - 2019 at both Lugogo Indoor Stadium and Nam- boole Stadium. Congratulations to 37/45 KAMPALA ROAD, P.O. BOX 7120, KAMPALA Telephone: 256-414-258441/6, all the winners in the different cat- 258061, 0312 392000, 0417 302000. Telex: 61069/61344; egories. Fax: 256-414-233818, Web site: www.bou.or.ug Kindly note that we are receiving applications for all our Professional and Academic Programmes for the January - May 2020 intake. We en- courage you to take up these pro- grammes to enrich your skills, aca- demic and professional credentials. Have a fruitful and blessed October! Bank of Uganda (BoU) has in the October global economy. Moreover, a combination of 2019 Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) widening fiscal and current account deficits, meeting decided to reduce the Central Bank coupled with public sector domestic financ- INSIDE Rate (CBR) by 1 percentage point to 9per- ing needs, could exert pressure on the lending centin response to the expected path of mac- interest rates leading to further moderation of Financial Services Industry news and high- roeconomic indicators and the international economic growth. lights economic environment. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) data for Highlights from the Registrar’s Office The economy continues to grow but at a September2019, released by UBOS, indi- and Training Department slowing rate. -

Access to Finance Report

Financial sector – Cameroon Final version- November 2012 In this annex you will find a full report on the Financial Sector of Cameroon resulting from our FSAS desk study. The report describes the level of Access to Finance in Cameroon and lists all banks active in Cameroon at the time. Through a desk- and internet study we have researched the services offered by each bank and which potentially could be useful for the Forestry Sector in Cameroon. Also through desk- and internet study we have researched the major Micro Finance Institutions of Cameroon and their suitability for servicing the Forestry Sector. This report also offers a full description of the identified Banks and Micro Finance Institutions. The report also lists those banks and MFI’s, which to our opinion, could potentially be the most interesting to approach for providing their services to the Forestry Sector. 1. Access to Finance in Cameroon According to the IMF (report 2009), the financial intermediation in Cameroon is among the lowest in Sub- Saharan Africa, with less than 5% of the population having access to banking services. The micro finance sector is becoming increasingly important but its supervision needs to be strengthened. 68.02% of firms identify access to and cost of finance as a major constraint1 in Cameroon. The Doing Business 2012 ranking of the World Bank, places Cameroon on rank 98 (out of 183), regarding Access to Credit in 2012. This while the ranking in 2011 was still significantly lower, namely 139. Improvements over the last year have been: an increase in strength of legal rights and increase of coverage of public registry. -

Product Differentiation Strategy and Perceived Financial Performance of Commercial Banks in Uganda

International Journal of Business and Management Invention (IJBMI) ISSN (Online): 2319-8028, ISSN (Print):2319-801X www.ijbmi.org || Volume 10 Issue 7 Ser. II || July 2021 || PP 52-60 Product Differentiation Strategy and Perceived Financial Performance of Commercial Banks in Uganda Kosea Wambaka School of Business Management and Public Administration, Texila, American University, Guliana, Omotayo Adeniyi ADEGBUYI Department of Business Management, Covenant University, Ota Nigeria, Corresponding Author: Omotayo Adeniyi ADEGBUYI ABSTRACT The banking landscape in Uganda is such that there is a section of commercial banks that has consistently posted impressive performance figures particularly over the last five years, while the performance of the others leaves a lot to be desired. This study’s purpose was to examine the effect of differentiation strategy on the financial performance of commercial banks in Uganda. The study employed a cross-sectional design characterized by a quantitative approach. The target population in this study constituted 210 Senior Managers and Chief Executives of 10 selected commercial banks in Uganda that have been rated as the best performing commercial banks in the last five years. A sample of 144 individuals was calculated for this study using Yamane’s (1967) formula, and the probability sampling technique of stratified proportionate random sampling was used in selecting Senior Managers of the selected commercial banks, and these were surveyed using a structured self-completion questionnaire. Quantitative data was analyzed descriptively using statistics such frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations; and inferentially using partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). The findings show a positive and statistically significant relationship between product differentiation strategy and financial performance in terms of ROI (β = 0.5841, ρ<0.05). -

EAC Financial Inclusion Stakeholder Mapping

EAC Financial Inclusion Stakeholder Mapping REPORT JANUARY - 2020 Supported by the: 1 Acknowledgements This report was produced by FinTechStage and Canela Consulting (our research partners). Contributors included Dr. Erin Taylor, Dr. Whitney Easton and Luis Carlos Serna Prati. Ariadne Plaitakis contributed material on regulation. Data analysis was carried out by Mariela Atannasova and Gawain Lynch. Infographics were produced by Ana Subtil, Mariela Atanassova and Whitney Easton. We would like to thank the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for their active support of the programme and the broad access to research material on Financial Inclusion. Lazaro Campos Co-Founder, FinTechStage January 2020 2 EAC FINANCIAL INCLUSION STAKEHOLDER MAPPING - REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The East African Community (EAC), a regional economic community, is often presented as a model of financial inclusion in Africa. Over the past few years, we have seen tremendous improvement across the region, but much remains to be done. The purpose of this body of work is to understand the state of financial inclusion across the EAC and identify how to advance. The first step is to map the financial inclusion landscape to identify stakeholders, gaps, and areas for intervention. We carried out data collection and network mapping for all six EAC Member States. In this report we identify: • All stakeholders who are working on financial inclusion issues in the EAC, including the financial sector, mobile network operators (MNOs), mobile money operators (MMOs), microfinance institutions -

THÈSE Présentée Par : Alexandra ZINS Soutenue Le : 26 Septembre 2018

UNIVERSITÉ DE STRASBOURG ÉCOLE DOCTORALE AUGUSTIN COURNOT (ED221) Laboratoire de Recherche en Gestion et Economie (LaRGE) THÈSE présentée par : Alexandra ZINS soutenue le : 26 septembre 2018 pour obtenir le grade de : Docteur de l’Université de Strasbourg Discipline : Sciences de Gestion Spécialité : Finance Essays on Banking in Africa THÈSE dirigée par : M. WEILL Laurent Professeur à l’Université de Strasbourg MEMBRES DU JURY : M. ALEXANDRE Hervé Professeur à l’Université Paris-Dauphine (rapporteur) M. GODLEWSKI Christophe Professeur à l’Université de Strasbourg (président du jury) M. MADIES Philippe Professeur à l’Université Grenoble-Alpes (rapporteur) Mme PELLETIER Adeline Lecturer at the Institute of Management Studies, Goldsmiths, University of London 1 2 A Simon et Marguerite, 3 « L’Université de Strasbourg n’entend donner ni approbation ni improbation aux opinions exprimées dans cette thèse. Ces opinions doivent être considérées comme propres à leur auteur. » 4 Acknowledgments C’est avec beaucoup d’émotions, et non sans soulagement, que j’achève la rédaction de cette thèse. Je tiens tout d’abord à remercier chaleureusement le Professeur Laurent Weill, qui a su m’accompagner tout au long de ce travail et qui m’a transmis son savoir et son goût pour la recherche. Je tiens à remercier Adeline Pelletier, Hervé Alexandre, Philippe Madiès et Christophe Godlewski pour leur participation au jury et le temps qu’ils ont dédié à lire ce travail . Merci infiniment à Simon, qui a toujours eu la patience pour m’aider, tant sur des questions de recherche (surtout économétriques) que sur le plan moral. Sans mon compagnon, il m’aurait été difficile d’achever ce travail.