Arxiv:1508.01482V2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Happy Valentine's Day! Sno-Ball Rolls with Record Crowd Sno-Ball '89

rrp Nrmn THE WEEKLY NEWSPAPER OF ST. LOUIS U. HIGH !220 couples packed tlle auditorium for Volume 53, Number 22 Friday, February 10, 1989 last weekend's Sno-Ball. Happy Valentine's Day! Sno-Ball rolls with record crowd Sno-Ball '89. "The Kinder, Gentler extremes. STIJCO President Mark Gunn Dance,"lived up to its name and was the gave the band a thumbs up because "they most sucessful SLUH winter dance in were original, energetic, and they all history. looked very pretty. " Junior Brad Hellwig The mammoth crowd of approxi gave a contrasting opinion, claiming that mately 220 couples huddled into the "it sounded like they were playing the auditorium for an evening of walking, same song over and over again. Also, they dancing, and reminiscing. Some expressed were a little heavy on the bass." Everyone disappointment about the decorations, seemed to agree, however, that the lead which seemed more appropriate for a singer bore an uncanny resemblance to Valentine's Day theme than the Sno-Ball the now grizzled-faced '88 SLUH grad, Dance. Last year's giant Billiken snow Dan Scheiber, who, strangely enough, man and smaller Billiken ice sculpture wasn't seen anywhere Saturday night were sorely missed. The decorations, In the absence of Mr. Art Zinsel however, did not interl'ere with the atmos meyer, Mr. Steve Brock acted as discipli phere, which was ripe with jollity and narian, and, by the end of the evening, he The Jargestooever PN Valentine edition gaiety. earned the title "The Enforcer." He grace begins on page 7. Reviews of the band, The -

Optimal Contracts with a Risk-Taking Agent

Theoretical Economics 15 (2020), 715–761 1555-7561/20200715 Optimal contracts with a risk-taking agent Daniel Barron Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University George Georgiadis Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University Jeroen Swinkels Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University Consider an agent who can costlessly add mean-preserving noise to his output. To deter such risk-taking, the principal optimally offers a contract that makes the agent’s utility concave in output. If the agent is risk-neutral and protected by limited liability, this concavity constraint binds and so linear contracts maximize profit. If the agent is risk averse, the concavity constraint might bind for some outputs but not others. We characterize the unique profit-maximizing contract and show how deterring risk-taking affects the insurance-incentive trade-off. Our logic extends to costly risk-taking and to dynamic settings where the agent can shift output over time. Keywords. Risk-taking, contract theory, gaming. JEL classification. D86, M2, M5. 1. Introduction Contractual incentives motivate employees, suppliers, and partners to exert effort, but improperly designed incentives can instead encourage excessive risk-taking. These risk- taking motives are most obvious when they have dramatic consequences for society as a whole. For instance, following the 2008 financial crisis, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke stated that “compensation practices at some banking organizations have led to misaligned incentives and excessive risk-taking, -

Kid Ink Releases 7 Series Ep Via Tha Alumni Music Group/88 Classic/Rca Records Available Now at All Digital Service Providers

KID INK RELEASES 7 SERIES EP VIA THA ALUMNI MUSIC GROUP/88 CLASSIC/RCA RECORDS AVAILABLE NOW AT ALL DIGITAL SERVICE PROVIDERS [May 5, 2017 – New York, NY] Today, Chart-topping, multi-platinum selling rapper and producer Kid Ink releases his 7 Series EP via Tha Alumni Music Group/88 Classic/ RCA Records. The 7 Series EP, which is now available at all digital service providers, has seven new tracks including already released "F With U" Feat. Ty Dolla $ign, "Lottery," "Supersoaka" and one bonus track, "Swish" ft. 2 Chainz. “F With U” Feat. Ty Dolla $ign, the EP’s first single, has been met with great critical praise with Rolling Stone describing the track sonically as, “…a pulsating, tropical-flavored beat…,” The FADER raving, “…a hot new track…[with] an incredibly danceable beat,” and VIBE calling the song, “…dance-floor ready.” The song was also the most added at Rhythmic radio last week and has over 11 million streams worldwide on Spotify, Apple Music and YouTube/Vevo since its release in April. This summer is looking to be bright for Ink with the release of his 7 Series EP and his song of summer contender, “F With U” feat. Ty Dolla $ign, climbing up the charts. 7 Series EP Track Listing: 1. Supersoaka 2. No Strings Feat. Starrah 3. F With U Feat. Ty Dolla $ign 4. Mochi 5. Sweet Chin Music 6. Bad Lil Vibe 7. Lottery 8. Swish Feat. 2 Chainz Listen/Buy to 7 Series EP: iTunes: http://smarturl.it/i7Series Spotify: http://smarturl.it/sp7Series Amazon Music: http://smarturl.it/az7Series Google Play: http://smarturl.it/gp7Series About Kid Ink: To date, Kid Ink has sold over 6.5 million singles worldwide since his 2014 major label debut album, My Own Lane (Tha Alumni Music Group/88 Classic/RCA Records) entered at #1 on Billboard’s Rap Albums chart, #2 on Top R&B/Hip Hop Albums chart and #3 on both the Top 200 and Top Digital Albums charts, according to Nielsen SoundScan. -

DJ Music Catalog by Title

Artist Title Artist Title Artist Title Dev Feat. Nef The Pharaoh #1 Kellie Pickler 100 Proof [Radio Edit] Rick Ross Feat. Jay-Z And Dr. Dre 3 Kings Cobra Starship Feat. My Name is Kay #1Nite Andrea Burns 100 Stories [Josh Harris Vocal Club Edit Yo Gotti, Fabolous & DJ Khaled 3 Kings [Clean] Rev Theory #AlphaKing Five For Fighting 100 Years Josh Wilson 3 Minute Song [Album Version] Tank Feat. Chris Brown, Siya And Sa #BDay [Clean] Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love TK N' Cash 3 Times In A Row [Clean] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful Frenship 1000 Nights Elliott Yamin 3 Words Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful [Louie Vega EOL Remix - Clean Rachel Platten 1000 Ships [Single Version] Britney Spears 3 [Groove Police Radio Edit] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And A$AP #Beautiful [Remix - Clean] Prince 1000 X's & O's Queens Of The Stone Age 3's & 7's [LP] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And Jeezy #Beautiful [Remix - Edited] Godsmack 1000hp [Radio Edit] Emblem3 3,000 Miles Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful/#Hermosa [Spanglish Version]d Colton James 101 Proof [Granny With A Gold Tooth Radi Lonely Island Feat. Justin Timberla 3-Way (The Golden Rule) [Edited] Tucker #Country Colton James 101 Proof [The Full 101 Proof] Sho Baraka feat. Courtney Orlando 30 & Up, 1986 [Radio] Nate Harasim #HarmonyPark Wrabel 11 Blocks Vinyl Theatre 30 Seconds Neighbourhood Feat. French Montana #icanteven Dinosaur Pile-Up 11:11 Jay-Z 30 Something [Amended] Eric Nolan #OMW (On My Way) Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [KBCO Edit] Childish Gambino 3005 Chainsmokers #Selfie Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [Radio Edit] Future 31 Days [Xtra Clean] My Chemical Romance #SING It For Japan Michael Franti & Spearhead Feat. -

Partner Név Jellemző Művek 100 BANDS PUBLISHING LUCKY YOU /#/ RINGER /#/ SIT DOWN /#/ KILLSHOT /#/ GOOD GUY FEAT JESSIE REYEZ

Partner név Jellemző Művek 100 BANDS PUBLISHING LUCKY YOU /#/ RINGER /#/ SIT DOWN /#/ KILLSHOT /#/ GOOD GUY FEAT JESSIE REYEZ 13 MOONS MUSIC BLOW /#/ KEEP PLAYING /#/ KEEP ME UP ALL NIGHT /#/ TOGETHER WE RUN /#/ BIGROOM BLITZ (RADIO MIX) 14 PRODUCTIONS SARL TIC TIC TAC /#/ OU SONT LES REVES /#/ PLACE DES GRANDS HOMMES /#/ QUI A LE DROIT /#/ JE SERAI LA POUR LA SUITE 1794 MUSIC AMERICAN BOOK OF SECRETS CUES /#/ AMERICA S BOOK OF SECRETS CUES /#/ BMOC /#/ LIMO HIP HOP VER 4 /#/ JOURNEY THROUGH TIME 1819 BROADWAY MUSIC DAYDREAM /#/ STORY S OVER (THE) /#/ STORY S OVER /#/ DAYDREAM (DJ NEWIK & STARWHORES REMIX) /#/ VADONATÚJ ÉRZÉS 1916 PUBLISHING MIDDLE (THE) /#/ HATE ME /#/ RUIN MY LIFE /#/ SLOW DANCE /#/ IF IT AIN T LOVE 23DB MUSIC RAPTURE /#/ HONEST SLEEP /#/ PALM DREAMS /#/ FLOWERS AND YOU /#/ DNA 24 HOUR SERVICE STATION ON THE LOOKOUT 2L E-SCORE UBI CARITAS /#/ SERENITY /#/ SNOW IN NEW YORK, FOR PIANO /#/ HUDSON /#/ ROXBURY PARK, FOR PIANO 2WAYTRAFFIC UK RIGHTS LTD TODAY S NAME - MAI JÁTÉKOSOK /#/ TODAY S NAMES /#/ WHAT IS THE ORDER - SORREND 3 WEDDINGS MUSIC SOMETHING ABOUT DECEMBER /#/ MAKE ME BELIEVE AGAIN /#/ HERE S TO NEVER GROWING UP /#/ JET BLACK HEART (START AGAIN) /#/ LET ME GO 360 MUSIC PUBLISHING LTD ONLY ONE /#/ IF YOU KNEW /#/ DON T BELONG /#/ HUMANICA /#/ MINIMAL LIFE 386MUSIC DON T LET GO /#/ VIOLET ALONE 3BEAT MUSIC LIMITED QUESTIONS /#/ MAN BEHIND THE SUN /#/ CONNECTION /#/ WHO'S LOVING YOU (PART 1) /#/ LINK UP 4 REAL MUSIC ANGELS LANDING /#/ EUGINA 2000 50 CENT MUSIC BEST FRIEND /#/ HATE IT OR LOVE IT /#/ HUSTLER S AMBITION -

Analyticity in Spaces of Convergent Power Series and Applications† 2

ANALYTICITY IN SPACES OF CONVERGENT POWER SERIES AND APPLICATIONS† †Preprint version: May 2015 Loïc Teyssier Laboratoire I.R.M.A., Université de Strasbourg [email protected] This work has been partially supported by French national grant ANR-13-JS01-0002- 01. Abstract. We study the analytic structure of the space of germs of an analytic function m at the origin of C , namely the space C z where z =(z1, ,z ), equipped with a conve- { } ··· m nient locally convex topology. We are particularly interested in studying the properties of analytic sets of C z as defined by the vanishing loci of analytic maps. While we notice { } that C z is not Baire we also prove it enjoys the analytic Baire property: the countable { } union of proper analytic sets of C z has empty interior. This property underlies a quite { } natural notion of a generic property of C z , for which we prove some dynamics-related { } theorems. We also initiate a program to tackle the task of characterizing glocal objects in some situations. Infinite-dimensional holomorphy, complex dynamical systems, holomorphic solu- tions of differential equations, Liouvillian integrability of foliations [2000][MSC2010] 46G20, 58B12, 34M99, 37F75 1. Introduction This article purports to provide a context in which the following results make sense: Corollary A. Fix m N. The generic finitely generated subgroup G< Diff(Cm,0) of germs ∈ m of biholomorphisms fixing 0 C , identified with a tuple of generators (∆1,...,∆n), is free. Besides the set of non-solvable∈ subgroups of Diff(C,0) generated by two elements is Zariski- full, in the sense that it contains (and, as it turns out, is equal to) an open set defined as the complement of a proper analytic subset of Diff(C,0)n. -

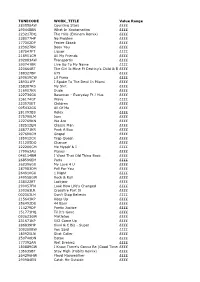

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 280558AW

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 280558AW Counting Stars ££££ 290448BN What In Xxxtarnation ££££ 223217DQ The Hills (Eminem Remix) ££££ 238077HP No Problem ££££ 177302DP Fester Skank ££££ 223627BR Been You ££££ 187547FT Liquor ££££ 218951CM All My Friends ££££ 292083AW Transportin ££££ 290741BR Live Up To My Name ££££ 220664BT The Girl Is Mine Ft Destiny's Child & Brandy££££ 188327BP 679 ££££ 290619CW Lil Pump ££££ 289311FP I Spoke To The Devil In Miami ££££ 258307KS My Shit ££££ 216907KR Dude ££££ 222736GU Baseman - Everyday Ft J Hus ££££ 236174GT Wavy ££££ 223575ET Children ££££ 095432GS All Of Me ££££ 281093BS Rolex ££££ 275790LM Ispy ££££ 222769KN We Are ££££ 182512EN Classic Man ££££ 288771KR Peek A Boo ££££ 297690CM Gospel ££££ 185912CR Trap Queen ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 222206GM Me Myself & I ££££ 179963AU Planes ££££ 048114BM I Want That Old Thing Back ££££ 268596EM Paris ££££ 262396GU My Love 4 U ££££ 287983DM Fall For You ££££ 264910GU 1 Night ££££ 249558GW Rock & Roll ££££ 238022ET Lockjaw ££££ 290057FN Look How Life's Changed ££££ 230363LR Crossfire Part Iii ££££ 002363LM Don't Stop Believin ££££ 215643KP Keep Up ££££ 256492DU 44 Bars ££££ 114279DP Poetic Justice ££££ 151773HQ Til It's Gone ££££ 093623GW Mistletoe ££££ 231671KP 502 Come Up ££££ 286839HP 6ixvi & C Biz - Super ££££ 309350BW You Said ££££ 180925LN Shot Caller ££££ 250740DN Detox ££££ 177392AN Wet Dreamz ££££ 180889GW I Know There's Gonna Be (Good Times)££££ 135635BT Stay High (Habits Remix) ££££ 264296HW Floyd Mayweather ££££ 290984EN Catch Me Outside ££££ 191076BP -

30, 1953 Mrs, Solluria Legal Voters Rounded Ambassador Project up for Quorum1 at Fire Tamer Favors Water Lown Bill on in a M Ed -Presid E N T Dist

Property of the Watertown Historical Society watertownhistoricalsociety.org A,n Oakville-Watertown Weekly (Entered .as second-class Jan. IS, 1948, si the post office aft Oakville, Conn., 'under flic Act of Mar. S, 1839') ¥©!., 6 No. Subscription Price, $&00 Per Year Single Copy, 6 Cents April 30, 1953 Mrs, SolLuria Legal Voters Rounded Ambassador Project Up For Quorum1 At Fire Tamer Favors Water Lown Bill On IN a m ed -Presid e n t Dist. Special Meeting - Tabled This Year To The streets .and, taverns were Library Ass'n" scouted. Tuesday evening in Referendum For Change In Gov't Officers and three trustees were search, of legal voters11 of the Oak- Rep. Arthur E. B. Tanner of elected at the annual meeting of Be Undertaken 1954 ville First, District. A special Woodbury, Speaker of the House, .'the Watertown Library Associa- .meeting of the fire district had told Town Times this week he tion's Board of Trustees held A Community Ambassador pro- been, called but lacked the IS per- Sewer Project Still favored passage of House Bill 752 Tuesday evening' In the library, ject for the town will not be 'un- sons necessary for a quorum to which proposes a. referendum on Officers elected were ' Mrs. Sol dertaken this year, according to open the meeting. the change in the form of govern- B. Luria," president; Barry L. the group of local citizens who A handful of voters were final- Stymied By Rd, Tap ment for the Town of Watertown, Morgan,, vice - president; Mrs. were studying the details, of' the ly located who 'were urged, to at- if the General Assembly fails to Board man G. -

Students Improve Testing Scores

RA"7AT FHSE PUBLIC LZ2P.ARX 1175 ST. GEORGE AVE. RAMSAY, H.J. 07065 RAHWAY ^ ^'* ttatb New Jersey's Oldest Weekly Newspaper-Established 1822 VOL. 165 NO. 48 RAHWAY. NEW JERSEY. THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 26. 1987 USPS 454-160 25 CENTS Students improve testing scores by Pal DiMaggio tuke the test again in the of Schools Frank Brunette Curriculum and Instruc- Student scores have "in- tenth, eleventh or twelfth said that 1987 results show- tion. creased tremendously" on grade. ed that students scored In 1985-86. the first year the High School Proficiency "There has been a above the national norm in the test was used as a Test (HSPT) according to tremendous increase across every one of 39 areas of graduation requirement, 76 1986-87 school year results the board in all areas," said testing. percent passed in reading. announced ut the Board of Alice DeSanlo, Director of Test results in 1983 71 percent passed in writing Education meeting held lust Student Personnel Services, showed 10 out of the 39 and 57 percent passed in week. in a presentation of lest areas scored below the na- math. results to the board. tional norm, he said. The HSPr has been a Scores for the 1987 88 Results of Iowa tests in SIGN OF THE TIMES ... The Informational message state-mandated graduation In 1986-87, 86.2 percent school year will have to grades K-8, HSPT scores in board at Hahway Htrjh School recently displayed a requirement since 1985-86 of the students achieved a meet a standard of u 75 per- grude 9 and Tests of "Thank You" to Merck and Co., Inc., and Junior testing achievement levels passing grade^ in reading, cent passing rate in each of Achievement and Proficien- Achievement (or their participation In the Applied in reading, writing and 86.1 percent"^ achieved a the three areas to achieve cy (TAP) in grades 10-11 Economics Program. -

1 E S T a B L =Sh .. !

==========================================.--�:,================================= 1��E�S_T�A�B�L��=SH�.. !�����86�·_3�._�_��������T�O�PE�K�A�.�K�A���S�Ai��;M�AR�C�H�2�2.�1�88�2�,���������VO�L=.�X�X�.�N=O=,�12�. not one bearer wo cultlvatton. 1'he A.II that Is clalmed as to the ot 'en Inches In diameter, and I have lost by gTIIsse., prevention 01 wldespreadlng and destructive oCany varIety ""n supertortry creamery i 1>-7\ side. com trees Which we '. •• '"\ Inen seon with a ete- produ. ts. wh>tt i hen ? Shall Wo that while my ueighbors, on every plata THE KANSAS FARMER. fires. the� are the Kreat agencies thllt have wrought original acknowledge rabbits, as I It skill and or others cnnnot be aunined of old orchnrds utmost destroyed, Now. snch 1\ wonderful change In lhe cllmateof the easteru cumrerence of trunk or a J nfl.y hu-hes, and the enterprlse having wllh t Are we til thnt sk llled utmost farmer hus trom onc to Cour dogs, why halt of Kamas. Even If no more ratn fILl's on the opre"d or branches or Corty reer, loaned tw,·nty by ourselves acknowledge every beauurut \Vft8 8. worth iabor and bustness with B not themlto xrd IH!:fl A very llLLlt!!trninlllg The Xa'!l.ltu Farmer Company, Proprietorl, earth nnw than In the e"rly d"l'S or the stale'. his bushels or fruit, sight g�llIg abl.Ityare iucompntilJle put g an� to a on wHl do what I have done. Tr, , Are we to trouble Top�ka, KanIa., tory, It fs beuer dlstrtbuted throughout lhe ••••on some distance to sec. -

Farmer's Repository

absurdities *m<l idelullot), is uoivrrsRlIy, P. S. — If yen have in your -School any poor children, whose parc.ms, guardians LIST OF U-1TTE11S FROM THE and almost exclusively taught; vrhilc the //I the Post-Office, or masters are not able to purchase. Bihl.-s l';r FARMER'S REPOSITORY. children of Christians are carefully in- To Parents <md Guardians of Children, Htnictr-d ia the language* of ancient Italy or Testaments for ihsir use,'- at the fore- going prices, they may be furnished QUA- A. and Masitrs of '4f>prcntirrst through- •nd Greece, and their minds familiariz- Mr. Anderson, Inn-krnprr ; J.,lm Able CHARLES-TOWN, (J.efcrsonCountyyVirgfnia,} PRINTED B7»RICHAR£) WILLIAMS. out the Commonwealth of Virginia. ed to all the impurities of the heathen TUITOt/SLY. FELLOW Cm ZENS, mythology; to the neglect of "thatwis- Q3T The several Printers of News- Pa- W. ld..n Ilrmtnn, Kl'z i Urinton, Wm Urnm, xlom which conaeth from above."—They A'VlreW Itdmii-u, Marti n Uillenyer, Wm C un ,'' In the -following Circular Letter, pers in Virginia, are requested to give Jcilin Hiiclun iBier. «wu, (No. 380. read with delight the history of the deso-' the foregoing LETTER and ADDRESS, at THURSDAY, JULY 20, 1815. (a copy of which is intended to l>c srnt to C, Vol. VIII.] lilting ambition of Alexander and Cffiiar, least one insertion in their respective Pa- John ClRrk,2i Nullmniel OVm.in, Ah • every Teacher of Youth within this Com- O'lUv'll, Josiuh Chiton, Dplin'CirJillc V ' and oth«:r votaries of false glory ; but are pers. -

FRANKIE CARLL PRODUCTIONS DJ SONG LIST Song Title Artist Song Title Artist Song Title Artist

FRANKIE CARLL PRODUCTIONS DJ SONG LIST Song Title Artist Song Title Artist Song Title Artist BEACH BOYS 25 OR 6 TO 4 CHICAGO A SONG FOR MAMA (Shortened Version) METRO STATION 2U DAVID GUETTA FT. JUSTIN BIEBERA SONG FOR MY DAUGHTER RAY ALLAIRE # 41 DAVE MATTHEWS BAND 3 BRITNEY SPEARS A SONG FOR MY SON DONNA LEE HONEYWELL #1 NELLY 3 (REMIX) A SONG FOR MY SON (Shortened Version) #BEAUTIFUL MARIAH CAREY 360 WILL HOGE A SONG FOR MY SON (Shortened Version) MIKKI VIERICK (EVERYTHING I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU BRYAN ADAMS 4 MINUTES MADONNA ft Justin Timberlake A STRING OF PEARLS GLENN MILLER ORCHESTRA (GET UP) I FEEL LIKE BEING A SEX MACHINE JAMES BROWN 4 ON THE FLOOR (Bridal Party Intro) GERALD ALBRIGHT A SUMMER SONG CHAD & JEREMY (GOD MUST HAVE SPENT) A LITTLE MORE TIME NSYNC 4:44 JAY Z A TEENAGER IN LOVE DION & THE BELMONTS (HOT S**T) COUNTRY GRAMMAR NELLY 409 BEACH BOYS A THOUSAND MILES VANESSA CARLTON (I CAN'T GET NO) SATISFACTION ROLLING STONES 5 O'CLOCK (CLEAN VERSION) T-PAIN FT. LILY ALLEN A THOUSAND STAR KATHY YOUNG & THE INNOCENTS (I CAN'T HELP) FALLING IN LOVE UB40 50 WAYS TO LEAVE YOUR LOVER PAUL SIMON A THOUSAND YEARS CHRISTINA PERRI (IT MUST'VE BEEN OL') SANTA CLAUS HARRY CONNICK, JR. 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN A THOUSAND YEARS THE PIANO GUYS (IT) FEELS SO GOOD STEVEN TYLER 500 MILES (I'M GONNA BE) PROCLAIMERS A WELL RESPECTED MAN THE KINKS (I'VE HAD) THE TIME OF MY LIFE BILL MEDLEY / JENNIFER WARNES5-1-5-0 DIERKS BENTLEY A WHITE SPORT COAT (AND A PINK CARNATION) MARTY ROBBINS (KEEP FEELING) FASCINATION HUMAN LEAGUE 7 DRAKE F./WIZKID & KYLA A WHOLE NEW WORLD PEABO BRYSON / REGINA BELLE (KISSED YOU) GOOD NIGHT GLORIANA 7 RINGS ARIANA GRANDE A WINK AND A SMILE HARRY CONNICK JR.