A Change in Circumstance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOURNAL and PROCEEDINGS

JOURNAL and PROCEEDINGS of The Royal Society of New South Wales Volume 143 Parts 1 and 2 Numbers 435–436 2010 THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF NEW SOUTH WALES OFFICE BEARERS FOR 2009-2010 Patrons Her Excellency Ms Quentin Bryce AC Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia. Her Excellency Professor Marie Bashir AC CVO Governor of New South Wales. President Mr J.R. Hardie, BSc Syd, FGS, MACE Vice Presidents Em. Prof. H. Hora Mr C.M. Wilmot Hon. Secretary (Ed.) Dr D. Hector Hon. Secretary (Gen.) Mr B.R. Welch Hon. Treasurer Ms M. Haire BSc, Dip Ed. Hon. Librarian vacant Councillors Mr A.J. Buttenshaw Mr J. Franklin BSc ANU Ms Julie Haeusler Dr Don Hector Dr Fred Osman A/Prof. W.A. Sewell, MB, BS, BSc Syd, PhD Melb FRCPA Prof. Bruce A. Warren Southern Highlands Rep. Mr C.M. Wilmot EDITORIAL BOARD Dr D. Hector Prof. D. Brynn Hibbert Prof. J. Kelly, BSc Syd, PhD Reading, DSc NSW, FAIP, FInstP Prof. Bruce A. Warren Dr M. Lake, PhD Syd Mr J. Franklin BSc ANU Mr B. Welch The Society originated in the year 1821 as the Philosophical Society of Australasia. Its main function is the promotion of Science by: publishing results of scientific investigations in its Journal and Proceedings; conducting monthly meetings; awarding prizes and medals; and by liason with other scientific societies. Membership is open to any person whose application is acceptable to the Society. Subscriptions for the Journal are also accepted. The Society welcomes, from members and non-members, manuscripts of research and review articles in all branches of science, art, literature and philosophy for publication in the Journal and Proceedings. -

LAYING CLIO's GHOSTS on the SHORES of NEW HOLLAND* the Title Does Not Foreshadow an Ex

EMPTY HISTORICAL BOXES OF THE EARLY DAYS: LAYING CLIO'S GHOSTS ON THE SHORES OF NEW HOLLAND* By DUNCAN ~T ACC.ALU'M HE title does not foreshadow an exhumation of the village Hampdens, as Webb T called them,! buried on the shores of Botany Bay. In fact, they were probably thieves, but let their ;-emains rest in peace. No, the metaphor in the title is from an analogy from a memorable controversy in value theory in Economics. 2 The title was meant to suggest the need for giving some historical content to the emotions that have accompanied discussions of the early period. Some of the figures which seem to have been conjured up by historical writers have been given malignancy but 110t identity. Yet these faceless men of the past, and the roles for which they have been cast, seem to distort the play of life. And indeed, it is perhaps because the historical boxes have remained unfilled, and because the background-the rest of the play and action-has not been fully explored, that some people of the early period, well known to us by name, have been interpreted in the light of twentieth-century prejudice and political controversy. We know all too little about the quality of day-to-day life in early Australia, the spiritual and material existence of the early Europeans, their energies, their activities and outlook. In the first stage of an inquiry I have been pursuing into our early social history, I am concerned not with these more elusive yet in a way more interesting questions, but in what sort of colony it was with the officers, the gaol and the port. -

E-Book Code: REAU1036

E-book Code: REAU1036 Written by Margaret Etherton. Illustrated by Terry Allen. Published by Ready-Ed Publications (2007) © Ready-Ed Publications - 2007. P.O. Box 276 Greenwood Perth W.A. 6024 Email: [email protected] Website: www.readyed.com.au COPYRIGHT NOTICE Permission is granted for the purchaser to photocopy sufficient copies for non-commercial educational purposes. However, this permission is not transferable and applies only to the purchasing individual or institution. ISBN 1 86397 710 4 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012 12345678901234 5 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345 -

"THE GREAT 'WESTEBN EOAD" Illustrated. by Frank Walker.FRAHS

"THE GREAT 'WESTEBN EOAD" Illustrated. By Frank Walker.F.R.A.H.S MAMULMft VFl A WvMAfclVA/tJt* . * m ■ f l k i n £ f g £ 1 J k k JJC " l l K tfZZ) G uild,n g j XoCKt AHEA . &Y0AtMY. * ' e x . l i e.k «5 — »Ti^ k W^ukeK.^-* crt^rjWoofi. f^jw. ^ . ' --T-* "TTT" CiREAT WESTERN BOAD” Illustrated. —— By Fra^fr talker-F.R.A.H,S Ic&Sc&M The Great Western Hoad. I ■ -— ' "..................... ----------- FORE W ORE ----------------- The Ji5th April,x815,was a"red-letter day" in the history of Hew South Wales,as it signalled the throwing open of the newly“discovered western country to settlement,and the opening of the new road,which was completed by William uox,and his small gang of labourers in January,of the same year. The discovery of a passage across those hither to unassailaole mountains by ulaxland,Lawson and wentworth,after repeated failures by no less than thirteen other expeditions;the extended discoveries beyond Blaxland s furthest point by ueorge William Evans,and the subsequent construction of the road,follow -ed each other in rapid sequence,and proud indeed was i.acquarie, now that his long cherished hopes and ambitions promised to be realised,and a vast,and hitherto unknown region,added to the limited area which for twenty-five years represented the English settlement in Australia. Separated as we are by more than a century of time it is difficult to realise what this sudden expansion meant to the tfeen colony,cribbed,cabbined and confined as it had been by these mysterious mountains,which had guarded their secret so well, '^-'he dread spectre of famine had once again loomed up on the horizon before alaxland s successful expedition had ueen carried out,and the starving stock required newer and fresher pastures if they were to survive. -

NEWSLETTER No 95 July – September 2013 Price $3.00 Free to Members of the Society

1 Bathurst District Historical Society Inc. NEWSLETTER No 95 July – September 2013 Price $3.00 Free to Members of the Society FROM THE PRESIDENT Blaxland’s talk at the Society’s Museum. The Bathurst District Historical Society continues to The various activities being held in conjunction with have a great deal happening at present and in many Ben Hall are in full swing with ever increasing areas. Our first International Museum Day was a interest in the event. It is quite amazing the number great success and there are improvements and of people who are receiving the Ben Hall Raid additions to be added into next year’s event. Weekend Festival e-newsletter to date. See further Samantha Friend did a great job in organising the information in this member’s newsletter. special day which saw several new members join the The Society has organised a ‘Historic Colonial Society. Houses’ bus trip to three homes at Parramatta. It is Since our last member’s newsletter actual taking place on Sunday 25th August and includes - construction work has commenced on the new Hambledon Cottage, Elizabeth Farm and Experiment garden at Old Government Cottage. The Society’s Farm Cottage. See further details in this newsletter training program for the new Mosaic software will but book early now as there are only 53 seats. take place in July to allow the Society to list all its I attended the autumn colours presentation evening collection with one or more photos of each item, which concluded the most successful range of details of the item’s history, who made the donation, functions over the three month period. -

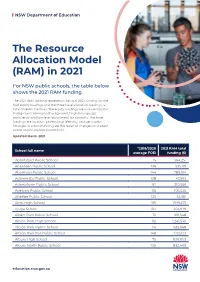

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

Melbourne Suburb of Northcote

ON STAGE The Autumn 2012 journal of Vol.13 No.2 ‘By Gosh, it’s pleasant entertainment’ Frank Van Straten, Ian Smith and the CATHS Research Group relive good times at the Plaza Theatre, Northcote. ‘ y Gosh, it’s pleasant entertainment’, equipment. It’s a building that does not give along the way, its management was probably wrote Frank Doherty in The Argus up its secrets easily. more often living a nightmare on Elm Street. Bin January 1952. It was an apt Nevertheless it stands as a reminder The Plaza was the dream of Mr Ludbrook summation of the variety fare offered for 10 of one man’s determination to run an Owen Menck, who owned it to the end. One years at the Plaza Theatre in the northern independent cinema in the face of powerful of his partners in the variety venture later Melbourne suburb of Northcote. opposition, and then boldly break with the described him as ‘a little elderly gentleman The shell of the old theatre still stands on past and turn to live variety shows. It was about to expand his horse breeding interests the west side of bustling High Street, on the a unique and quixotic venture for 1950s and invest in show business’. Mr Menck was corner of Elm Street. It’s a time-worn façade, Melbourne, but it survived for as long as consistent about his twin interests. Twenty but distinctive; the Art Deco tower now a many theatres with better pedigrees and years earlier, when he opened the Plaza as a convenient perch for telecommunication richer backers. -

Wreck of the 'Elizabeth' Rea~ As Follows: Number of Guns Raised

TheWreckof the'Elizabeth' TheV\Teckof the'ElizabetH This is number 1 in the series Studies in Historical Archaeology, GraemeHenderson published by the Australian Society for Assistant Curator of Marine Archaeology Historical Archaeology, in the Western Australian Museum Department of Archaeology, University of Sydney, Sydney, N.S.W. 2006. General editors: Judy Birmingham, M.A., Senior Lecturer in Archaeology, University of Sydney. R. Ian Jack, M.A., Ph.D., F.R.Hist.S., Associate Professor of History, University of Sydney. Further titles in this series include: Elizabeth Farm House, Parramatta; James King's Pottery at Irrawang, N.S. W.; The Tasmanian Aboriginal Settlement at Wybalenna, Flinders Island; Reprinted Catalogues of Some Nineteenth-Century Australian Potteries. Studies in Historical Archaeology No.1 Sydney 1973. Acknowledgments I want to express my thanks to various people who have given me assistance during the preparation of this study. Mr David Hutchison of the Western Australian Museum provided the information con tained in the appendix concerning the chronometer. Dr Barry Wilson of the Western Australian Museum identified the shells found on the site for me. Dr Ian © Graeme Henderson and Crawford of the Western Australian Museum provided the Australian Society for Historical Archaeology some information concerning the iron guns found on National Library of Australia card number and the site. ISBN 0 909797 01 3 Mr Ron Parsons of the Australasian Maritime Registered at the G.P.O., Sydney for transmission Historical Society provided me with information on through the post as a book. the background of the owner of the 'Elizabeth'. Sketch maps given to the Museum by Underwater Explorers Club members and by Mr John Crookes Six hundred copies printed ofwhich this is number were of assistance in locating concentrations of material on the site. -

Grenville Kate 320 Compress.Mp3

Grenville Kate 320 compress.mp3 [00:00:00] Interviewer Welcome to the Inner West Library Speaker series. Before we begin today, I would like to acknowledge the Gadigal and Wangal people of the Eora nation on which this podcast is produced and pay my respects to Elders past, present and emerging from across all lands this podcast reaches. Kate Grenville is one of Australia's most celebrated writers. Her international bestseller, The Secret River, was awarded local and overseas prizes, has been adapted for the stage and as an acclaimed television miniseries and is now a much-loved classic. Grenville's other novels include Sarah Thornhill, The Lieutenant, Dark Places and the Orange Prize Winner The Idea of Perfection. Her most recent books are two works on non-fiction, One Life: My Mother's Story and The Case Against Fragrance. She has also written three books about the writing process. In 2017, Grenville was awarded the Australia Council Award for Lifetime Achievement in Literature. She currently lives in Melbourne. What if Elizabeth Macarthur, wife of the notorious John Macarthur, wool Baron in the earliest days of Sydney had written a shockingly frank secret memoir? And what if novelist Kate Grenville had miraculously found and published it? That's the starting point for A Room Made of Leaves, a playful dance of possibilities between the real and the invented. Marriage to a ruthless bully, the impulses of her heart, the search for power in a society that gave women none. This Elizabeth Macarthur manages her complicated life with spirit and passion, cunning and sly wit. -

12925 ID Bentley1982penrithl

PENRITH LAKES DEVELOPMENT SCHEME REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL STUDY REPORT ON THE NON-ABORIGINAL ENVIRONMENTAL HERITAGE RESEARCHED BY MS. FRAN BENTLEY FOR MS. J. BIRMINGHAM UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY JUNE 1982 -'" --- CITY OF PLNRITH w w o 01 \ o t'27l+ 500 N w' o o PLAN m o "(\,.1. SHOWING PART OF THE LAND ZONED RURAL A2 INTERIM DEVE.LOPMENT ':2:~ 000 N ORDER NI? 93 CITY OF PENRITH. IS u PARISH CA~,TLEREAGH COUNTY CUMBE.RLAND (\ 'O() 200 +O~i 500 ,,,;P SCA~E. ~">/ / / / "', ''<-<:'A' ,-, RAV·\ ~.~ ,"",'l/\J$ / / ...... ',:. ; '. , \, ___ J 1-- I 1271 soc \1 \ ---~---+ ---- ._. ., .,.~~~ ", \ 11 ,I --t ,j j-, i ! , , ~ A q ST1,'\i'SCN -~~--~-------~-~---r - - -f--,----~.-----~~ . /-., , .I1-~ ; < .' w..; I Cl I c l/" w, / 0, o ". b,','I' o -- -~, 4- -'-_-.(."""_ -----t - -" --d-f \, ); / , I ~--' w 1.1);' o ! ,; o<c, Ni 1' N _______ ~ _~ _--,- __'2_7_0000 N . ' C.·,5CC N -, 126", 500 11 \ , , " " !2(C~OOO \ : :-;." ____-l-- - --~---. '. -- ,'. '."l , '~ j~ j I i 1'2:0 8 COO N ----~---t-- --, +-_. ! I / -' -,1.- --'~ I '.'. , , ___ I ... ' ------ - - --- C4MAlCO . ----------- PQODUc1S I/ ' , .... ' PT";' '-r ... ', - - - :..., -,0.< '," 1267000 N -~ -~-"-------o::-.:t_-------:-~, '--,.~,"-------,-.-.~ --~""'------- t-i- --1- ---~-- i- 1206500 N ---+- --- ---·--I----~-- <"\.'" .........", >:- '" I 126::; CC;:) ~i 1266000 N - --,r'-- -i- , I, I / " '; LEGEND --~------ ----NOTE. : ~ .., ....... ;' .. .. BLL'[ ~1ETAL INDUSTRIES LTD PLAN SHOWS LANDS IN WHICH THE FARLEY AND LEWERS LTD RESPECTIVE COMPANIES HAVE A DIRECT .+ •••••• , PIONEER CONCRETE SERVICES LTD OR BENEFICIAL INTEREST AT '2 ,IIOIi£~BO / READY M IXED CONCRETE LTD GRAVEL BOUNDARY FROM B M I ............ PENRITH LAkES DEVUOPMENT DRAWING Ne MS -'291/A AND IS CORPORATION LTD APPROXIMATE ONLY , AREA "ZONED I. RURAL "A '2' UNC'U: I DO. -

Sadie Heckenberg Thesis

!! ! "#$%&"'!()#*$!*+! ,&$%#*$!*+!! !"#$%&$'()*+(,')%(#-.*/(#01%,)%.* $2"#-)2*3"41*5'.$#"'%.*4(,*6-1$-"4117*849%* :%.%4"&2* !"4&$'&%.** * * * Sadie Heckenberg BA Monash, BA(Hons) Monash Swinburne University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Of Doctor of Philosophy July 2018 #$%&'#(&!! ! ! ! Indigenous oral history brings life to our community narratives and portrays so well the customs, beliefs and values of our old people. Much of our present day knowledge system relies on what has been handed down to us generation after generation. Learning through intergenerational exchange this Indigenous oral history research thesis focuses on Indigenous methodologies and ways of being. Prime to this is a focus on understanding cultural safety and protecting Indigenous spoken knowledge through intellectual property and copyright law. From an Indigenous and Wiradjuri perspective the research follows a journey of exploration into maintaining and strengthening ethical research practices based on traditional value systems. The journey looks broadly at the landscape of oral traditions both locally and internationally, so the terms Indigenous for the global experience; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander for the Australian experience; and Wiradjuri for my own tribal identity are all used within the research dialogue. ! ! "" ! #$%&'()*+,-*&./" " " " First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge and thank the Elders of the Wiradjuri Nation. Without their knowledge, mentorship and generosity I would not be here today. Most particularly my wonderful Aunty Flo Grant for her guidance, her care and her generosity. I would like to thank my supervisors Professor Andrew Gunstone, Dr Sue Anderson and Dr Karen Hughes. Thank you for going on this journey of discovery and reflection with me. -

Influx of Oriminals Aot

1856. VICTORIA. INFLUX OF ORIMINALS AOT. Return to WIt Address qf the Legislative Assembly, 9th December, 1856. (Mr. G?·eeves.) Ordered by the Legislative Assembly to be p1'inted, IOU. Dccembel', 1856. No. 43. SIR, Toorac, neal' lVlelbourne, 14th April, 1856: In transmitting for the consideration of Her Majesty's Government an Act passed by the Legislature of this Colony, on the 23rd day of January last, entitled "An Act to continuefQ1' a,limited period WIt Act entitled, 'An Act to prevent the influx qf Criminals into Victoria,''' I have the honor to state that acting under the advice of the Attorney-General of this Colony, I have given my assent thereto in the name of Her Majesty. The reasons lYhich actuated Governor, the late Sir Charles Hotham in assenting to the Act of which the present Act is the renewal, and with respect to which he pointed out the policy and expediency in his despatch, No. 150 of the 18th November, 1854, have also greatly influenced my own decision. I have, &c., &c., (Signed) EDWARD MACARTHUR. The Right Honorable, Hy. Labou,chere, M.P. (Gopy.) No. 44. SIR, Toorac, near Melbourne, 15th April, 1856. an tJns occasion I do myself the honor to refer to a despat<lh of Governor, the late Sir Chas. Sir Cbas. Hotllam, to See. Hotham, on the subject of the infiu.."{ of Criminals into Vietoria from tIle neighbouring Colony of of State, No. 1M. of Tasmania. ' 18th November, 1854. As ilie Secretary of State in replying to ws despatch, W!J.'l pleased to address several remarks Lord John R.ussell to Sir to Sir Chas.