The ABC About Collecting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grosvenor Prints CATALOGUE for the ABA FAIR 2008

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN Tel: 020 7836 1979 Fax: 020 7379 6695 E-mail: [email protected] www.grosvenorprints.com Dealers in Antique Prints & Books CATALOGUE FOR THE ABA FAIR 2008 Arts 1 – 5 Books & Ephemera 6 – 119 Decorative 120 – 155 Dogs 156 – 161 Historical, Social & Political 162 – 166 London 167 – 209 Modern Etchings 210 – 226 Natural History 227 – 233 Naval & Military 234 – 269 Portraits 270 – 448 Satire 449 – 602 Science, Trades & Industry 603 – 640 Sports & Pastimes 641 – 660 Foreign Topography 661 – 814 UK Topography 805 - 846 Registered in England No. 1305630 Registered Office: 2, Castle Business Village, Station Road, Hampton, Middlesex. TW12 2BX. Rainbrook Ltd. Directors: N.C. Talbot. T.D.M. Rayment. C.E. Ellis. E&OE VAT No. 217 6907 49 GROSVENOR PRINTS Catalogue of new stock released in conjunction with the ABA Fair 2008. In shop from noon 3rd June, 2008 and at Olympia opening 5th June. Established by Nigel Talbot in 1976, we have built up the United Kingdom’s largest stock of prints from the 17th to early 20th centuries. Well known for our topographical views, portraits, sporting and decorative subjects, we pride ourselves on being able to cater for almost every taste, no matter how obscure. We hope you enjoy this catalogue put together for this years’ Antiquarian Book Fair. Our largest ever catalogue contains over 800 items, many rare, interesting and unique images. We have also been lucky to purchase a very large stock of theatrical prints from the Estate of Alec Clunes, a well known actor, dealer and collector from the 1950’s and 60’s. -

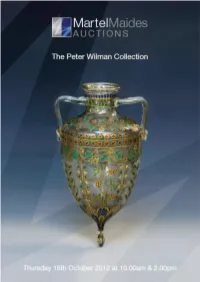

The Wilman Collection

The Wilman Collection Martel Maides Auctions The Wilman Collection Martel Maides Auctions The Wilman Collection Martel Maides Auctions The Wilman Collection Lot 1 Lot 4 1. A Meissen Ornithological part dessert service 4. A Derby botanical plate late 19th / early 20th century, comprising twenty plates c.1790, painted with a central flower specimen within with slightly lobed, ozier moulded rims and three a shaped border and a gilt line rim, painted blue marks square shallow serving dishes with serpentine rims and and inscribed Large Flowerd St. John's Wort, Derby rounded incuse corners, each decorated with a garden mark 141, 8½in. (22cm.) diameter. or exotic bird on a branch, the rims within.ects gilt £150-180 edges, together with a pair of large square bowls, the interiors decorated within.ects and the four sides with 5. Two late 18th century English tea bowls a study of a bird, with underglaze blue crossed swords probably Caughley, c.1780, together with a matching and Pressnumern, the plates 8¼in. (21cm.) diameter, slop bowl, with floral and foliate decoration in the dishes 6½in. (16.5cm.) square and the bowls 10in. underglaze blue, overglaze iron red and gilt, the rims (25cm.) square. (25) with lobed blue rings, gilt lines and iron red pendant £1,000-1,500 arrow decoration, the tea bowls 33/8in. diameter, the slop bowl 2¼in. high. (3) £30-40 Lot 2 2. A set of four English cabinet plates late 19th century, painted centrally with exotic birds in Lot 6 landscapes, within a richly gilded foliate border 6. -

Here to See Ceramics in the U.S

www.ceramicsmonthly.org Editorial [email protected] telephone: (614) 895-4213 fax: (614) 891-8960 editor Sherman Hall assistant editor Renee Fairchild assistant editor Jennifer Poellot publisher Rich Guerrein Advertising/Classifieds [email protected] (614) 794-5809 fax: (614) 891-8960 [email protected] (614) 794-5866 advertising manager Steve Hecker advertising services Debbie Plummer Subscriptions/Circulation customer service: (614) 794-5890 [email protected] marketing manager Susan Enderle Design/Production design Paula John graphics David Houghton Editorial, advertising and circulation offices 735 Ceramic Place Westerville, Ohio 43081 USA Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is published monthly, except July and August, by The American Ceramic Society, 735 Ceramic Place, Westerville, Ohio 43081; www.ceramics.org. Periodicals postage paid at Westerville, Ohio, and additional mailing offices. Opinions expressed are those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent those of the editors or The Ameri can Ceramic Society. subscription rates: One year $32, two years $60, three years $86. Add $25 per year for subscriptions outside North America. In Canada, add 7% GST (registration number R123994618). back issues: When available, back issues are $6 each, plus $3 shipping/ handling; $8 for expedited shipping (UPS 2-day air); and $6 for shipping outside North America. Allow 4-6 weeks for delivery. change of address: Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation De partment, PO Box 6136, Westerville, OH 43086-6136. contributors: Writing and photographic guidelines are available on request. Send manuscripts and visual sup port (slides, transparencies, etc.) to Ceramics Monthly, 735 Ceramic PI., Westerville, OH 43081. -

9. Ceramic Arts

Profile No.: 38 NIC Code: 23933 CEREMIC ARTS 1. INTRODUCTION: Ceramic art is art made from ceramic materials, including clay. It may take forms including art ware, tile, figurines, sculpture, and tableware. Ceramic art is one of the arts, particularly the visual arts. Of these, it is one of the plastic arts. While some ceramics are considered fine art, some are considered to be decorative, industrial or applied art objects. Ceramics may also be considered artifacts in archaeology. Ceramic art can be made by one person or by a group of people. In a pottery or ceramic factory, a group of people design, manufacture and decorate the art ware. Products from a pottery are sometimes referred to as "art pottery".[1] In a one-person pottery studio, ceramists or potters produce studio pottery. Most traditional ceramic products were made from clay (or clay mixed with other materials), shaped and subjected to heat, and tableware and decorative ceramics are generally still made this way. In modern ceramic engineering usage, ceramics is the art and science of making objects from inorganic, non-metallic materials by the action of heat. It excludes glass and mosaic made from glass tesserae. There is a long history of ceramic art in almost all developed cultures, and often ceramic objects are all the artistic evidence left from vanished cultures. Elements of ceramic art, upon which different degrees of emphasis have been placed at different times, are the shape of the object, its decoration by painting, carving and other methods, and the glazing found on most ceramics. 2. -

Philippa H Deeley Ltd Catalogue 17 Oct 2015

Philippa H Deeley Ltd Catalogue 17 Oct 2015 1 A Pinxton porcelain teapot decorated in gilt with yellow cartouches with gilt decoration and hand hand painted landscapes of castle ruins within a painted botanical studies of pink roses, numbered square border, unmarked, pattern number 300, 3824 in gilt, and three other porcelain teacups and illustrated in Michael Bertould and Philip Miller's saucers from the same factory; Etruscan shape 'An Anthology of British Teapots', page 184, plate with serpent handle, hand painted with pink roses 1102, 17.5cm high x 26cm across - Part of a and gilt decoration, the saucer numbered 3785 in private owner collection £80.00 - £120.00 gilt, old English shape, decorated in cobalt blue 2 A Pinxton porcelain teacup and saucer, each with hand painted panels depicting birds with floral decorated with floral sprigs and hand painted gilt decoration and borders, numbered 4037 in gilt landscapes with in ornate gilt surround, unmarked, and second bell shape, decorated with a cobalt pattern no. 221, teacup 6cm high, saucer 14.7cm blue ground, gilt detail and hand painted diameter - Part of a private owner collection £30.00 landscape panels - Part of a private owner - £40.00 collection £20.00 - £30.00 3 A porcelain teapot and cream jug, possibly by 8A Three volumes by Michael Berthoud FRICS FSVA: Ridgway, with ornate gilding, cobalt blue body and 'H & R Daniel 1822-1846', 'A Copendium of British cartouches containing hand painted floral sparys, Teacups' and 'An Anthology of British Teapots' co 26cm long, 15cm high - -

Ian Marr Rare Books: Catalogue 18

CATALOGUE 18 VARIA Item 59 IAN MARR RARE BOOKS IAN MARR RARE BOOKS 23 Pound Street Liskeard Cornwall PL14 3JR England Enquiries or orders may be made by telephone, which will be answered by Ian or Anne Marr: 01579 345310 or, if calling from abroad: 0044 1579 345310 or, mobile: 0773 833 9709 PLEASE NOTE OUR NEW EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] Prices are net, postage extra, usual terms apply. Payment may be by cheque, direct transfer, or Paypal. Institutional libraries may have terms to suit their budgetary calendars. We will gladly supply more detailed descriptions, further images, etc. Books may be returned for any reason whatsoever, within the usual time frame, but in that event please let us know as soon as possible. If visiting, please contact us first to make arrangements. The ancient Cornish town of Liskeard is about 20 minutes, by car or railway, west of Plymouth; or 4 ½ hours from London. We are always interested to hear of books, manuscripts, ephemera, etc., which may be for sale, wherever they may be, and we are very happy to travel. Over the years, we have also conducted many cataloguing projects, and valuations for probate, insurance, or family division. 1. [ARMY MUSICIANS] [Changing the Guard at St. James's Palace, 1792] [London, 1792] £275 hand-col’d engraving, 15.2 x 20.6 inches [S], proof before letters, unframed (one or two short marginal repairs and short tear just entering image; paper slightly toned, especially on the verso), paper watermarked “W. King,” numbered “58” within the plate, top right The National Army Museum, which also has this image of the Coldstream Guards, comments on the presence of the three African or Caribbean Musicians in ceremonial dress and “splendid turbans,” and that many such musicians were recruited into the British Army in the 18th century, and that they also had an important role on the battlefield, by communicating orders via their instruments. -

View Or Download the Dealers List Here

DEALERS Compiled by Robin Hildyard FSA (Last updated July 2021) “CHINA-MEN. This business is altogether shopkeeping, and some of them carry on a very considerable trade, joining white flint glass, fine earthenware and stoneware, as well as teas, with their china ware. They usually take with an apprentice from 20 to 50£, give a journeyman 20 to 30£ a year and his board, and employ a stock of 500£ and often more” A General Description of all Trades digested in alphabetical order Printed by T.Walker at the Crown & Mitre, opposite Fetter Lane, Fleet Street 1747. --------------------------------------------------------------- “The Earthen-Ware Shop is a Dependant on the Pot-House. They buy their Goods from several Houses in England, from Holland, and at the Sales of the East-India Company. They generally deal in Tea, Coffee and Chocolate” R.Campbell, The London Tradesman, London 1747 ----------------------------------------------- This list, which can never be complete, includes retailers with their shops and warehouses, factory shops, auctioneers, suppliers of tools and materials to the pottery trade, independent enamellers, gilders and printers together with their suppliers, japanners, glass cutters, glass engravers, glass enamellers, china menders, toymen, jewellers, confectioners, wine merchants and other trades likely to be involved in selling, embellishing or hiring china, earthenware or glass. ----------------------------------------------------------- ANONYMOUS: 1735, at the Glass Sellers Arms, next door to the Globe Tavern in Fleet Street, to be sold very cheap, “very cheap China Ware” and glass etc. (Daily Journal 30 Aug. 1735, Buckley notes Ceramics Dept. library 9B10). This is Benjamin Payne (qv), and see also under Mr.Ward at this address in 1736. -

The National Gallery of Canada: a Hundred Years of Exhibitions: List and Index

Document generated on 09/28/2021 7:08 p.m. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review The National Gallery of Canada: A Hundred Years of Exhibitions List and Index Garry Mainprize Volume 11, Number 1-2, 1984 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1074332ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1074332ar See table of contents Publisher(s) UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des universités du Canada) ISSN 0315-9906 (print) 1918-4778 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Mainprize, G. (1984). The National Gallery of Canada: A Hundred Years of Exhibitions: List and Index. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 11(1-2), 3–78. https://doi.org/10.7202/1074332ar Tous droits réservés © UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Association d'art des universités du Canada), 1984 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ The National Gallery of Canada: A Hundred Years of Exhibitions — List and Index — GARRY MAINPRIZE Ottawa The National Gallerv of Canada can date its February 1916, the Gallery was forced to vacate foundation to the opening of the first exhibition of the muséum to make room for the parliamentary the Canadian Academy of Arts at the Clarendon legislators. -

Oriental & European Ceramics & Glass

THIRD DAY’S SALE WEDNESDAY 24th JANUARY 2018 ORIENTAL & EUROPEAN CERAMICS & GLASS Commencing at 10.00am Oriental and European Ceramics and Glass will be on view on: Friday 19th January 9.00am to 5.15pm Saturday 20th January 9.00am to 1.00pm Sunday 21st January 2.00pm to 4.00pm Monday 22nd January 9.00am to 5.15pm Tuesday 23rd January 9.00am to 5.15pm Limited viewing on sale day Measurements are approximate guidelines only unless stated to the contrary Enquiries: Andrew Thomas Enquiries: Nic Saintey Tel: 01392 413100 Tel: 01392 413100 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 661 662 A large presentation wine glass and a pair of wine glasses Two late 18th century English wine glasses, one similar the former with bell shaped bowl engraved with the arms of and an early 19th century barrel-shaped tumbler the first Weston, set on a hollow knopped stem and domed fold over two with plain bowls and faceted stems, 13.5 cm; the third foot, 27 cm high, the pair each with rounded funnel shaped engraved with floral sprays and on faceted stem, 14 cm; the bowl engraved with an eagle’s head set on a double knopped tumbler engraved with urns, paterae and swags with the stem and conical foot, 23 cm high. initials ‘GS’,11 cm (4). *£200 - 250 *£120 - 180 663 A George Bacchus close pack glass paperweight set with various multi coloured canes and four Victoria Head silhouettes, circa 1850, 8 cm diameter, [top polished]. *£300 - 500 664 665 A Loetz Phanomen glass vase of A Moser amber crackled glass vase of twelve lobed form with waisted neck shaped globular form, enamelled with and flared rim, decorated overall with a a crab, a lobster and fish swimming trailed and combed wave design, circa amongst seaweed and seagrass, circa 1900-05, unmarked, 19 cm high. -

March 2007 Volume 8 Issue 1 T RENTON POTTERIES

March 2007 Volume 8 Issue 1 T RENTON POTTERIES Newsletter of the Potteries of Trenton Society Mayer’s Pottery and a Portneuf /Quebec Puzzle Jacqueline Beaudry Dion and Jean-Pierre Dion Spongeware sherds found in the dump site ENT PROCESS/FEB 1st 1887” and deco- of Mayer’s Arsenal Pottery in Trenton, rated with the cut sponge chain motif so New Jersey, revealed the use of several mo- popular in England and Scotland. Many tifs including the chain or rope border that of the sponge decorated ware found in was used later in Beaver Falls, Pennsyl- the Portneuf-Quebec area (and thus vania. Those cut sponge wares, when found called Portneuf wares) were actually in the Quebec area, are dubbed “Portneuf” made in Scotland, especially those de- and generally attributed to the United picting cows and birds. Finlayson Kingdom, in particular to Scotland. The (1972:97) naturally presumed the barrel mystery of the Portneuf chain design iron- had been produced in Scotland, al- stone barrel (Finlayson, 1972:97 ) is no though his research in England and more a puzzle: a final proof of its United Scotland failed to show any record of States origin is provided by a patent such a name or such a patent. “Could granted to J. S. Mayer in 1887. this J. S. Mayer,” he wrote, “have been associated with the John Thomson Ann- he small ironstone china barrel field Pottery [Glasgow, Scotland]? Per- T found in the Province of Quebec haps his process was used in the Thom- and illustrated here (Figure 1), is ap- son Pottery. -

Stoke on Trent Parish Register, 1754-1812

1926-27. STOKE-UPON-TRENT. 1754-1812 Staffordshire Staffordshire fldarisb IRegisters Society. E d ito r a n d H o n . S e c r e t a r y : PERCYSample W. CountyL. ADAMS, F.S.A., Woore ‘Manor, via Crewe. Studies D e a n e r y o f S t o k e -u p o n -T r e n t . Stoke Hipon=n*ent pansb IRegtster P A R T IV. P r i v a t e l y p r i n t e d for t h e Staffordshire P a r is h R e g ister s So c i e t y . A ll Comtnu?ticafions respecting the printing and transcription oj Registers and the issue of the parts should be addressed to the Edttor. •% Attention is especially directed to Notices on inside of Cover. Staffordshire The transcription of the Registers of Stoke-upon- Trent was undertaken by the late Rev. Sanford W . Hutchinson, Vicar of Blurton. Before his death in 1919, he completed them down to the year 1797 for Births and Burials, and to 1785 in Marriages, when it was continued by Mr. E. C. SampleMiddleton, of CountyStreetly. The proofs for this Vol. have been corrected for the press by the Rev. Douglas Crick, M .A ., the present Rector of Stoke-upon- Trent. The best thanks are due from the Society to those three gentlemen for their voluntary work. P. W.L.A.Studies i^tnkr flmslj Ulster. Staffordshire Marriages, Apr. 14, 1754, to April 5th, 1796, nearly all signed by J. -

Clubhouse Network Newsletter Issue

PLEASE Clubhouse Network TAKE ONE Newsletter THEY’RE FREE Hello everyone, this is the sixteenth edition of the Clubhouse Network Newsletter made by volunteers and customers of the Clubhouse Community. Thanks to everyone who made contributions to this issue. We welcome any articles or ideas from Clubhouse customers. Appetite’s Big Feast in Hanley September saw Appetite’s Big Feast return to the streets of Hanley. Giant Jenga from Block of NoFit The Amazing Giant Jenga Fillage State Circus and Motionhouse is almost complete here Fillage performed acrobatics Be amazed by the colourful and circus routines all to a jazz world of Fantabulosa. soundtrack. Museum of the Moon Museum of the Moon, displayed at the King’s Hall, was a spectacular seven-metre-wide, floating moon sculpture. Viewers basked under the Fantabulosa by moonlight of this beautifully lit Ticker Tape Parade installation featuring a stellar The performance featured surround soundtrack which wonderful interactive story time Bingo Lingo lifted you away onto another sessions all whilst dressed in An oversized street bingo act! plane. fabulous outfits. Have fun with this Sudoku Puzzle! Gladstone Museum A Plate Jigger Stacks of Saggers Members visited (The solution is on the Gladstone Clubhouse notice boards) Musuem on The Newsletter Online Heritage The current newsletter and back issues are Weekend which now available online. Scan this QR Code to be saw free entry to taken to the webpage where you can view the many museums newsletters. accros the country. People enjoyed watching the skilled workers then followed up with a cuppa in the café. A Ceramic Flower Maker Use the QR code or type in this URL http://www.brighter-futures.org.uk/clubhouse- network-newsletter Newsletter Availability Photography Group As well as the print edition, the newsletter is Learn to take better photos! The available in other formats.