Ashmolean Papers Ashmolean Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tracing the Origin of Blue and White Chinese Porcelain Ordered for the Portuguese Market During the Ming Dynasty Using INAA

Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (2013) 3046e3057 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Tracing the origin of blue and white Chinese Porcelain ordered for the Portuguese market during the Ming dynasty using INAA M. Isabel Dias a,*, M. Isabel Prudêncio a, M.A. Pinto De Matos b, A. Luisa Rodrigues a a Campus Tecnológico e Nuclear/Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, EN 10 (Km 139,7), 2686-953 Sacavém, Portugal b Museu Nacional do Azulejo, Rua da Madre de Deus no 4, 1900-312 Lisboa, Portugal article info abstract Article history: The existing documentary history of Chinese porcelain ordered for the Portuguese market (mainly Ming Received 21 March 2012 dynasty.) is reasonably advanced; nevertheless detailed laboratory analyses able to reveal new aspects Received in revised form like the number and/or diversity of producing centers involved in the trade with Portugal are lacking. 26 February 2013 In this work, the chemical characterization of porcelain fragments collected during recent archaeo- Accepted 3 March 2013 logical excavations from Portugal (Lisbon and Coimbra) was done for provenance issues: identification/ differentiation of Chinese porcelain kilns used. Chemical analysis was performed by instrumental Keywords: neutron activation analysis (INAA) using the Portuguese Research Reactor. Core samples were taken from Ancient Chinese porcelain for Portuguese market the ceramic body avoiding contamination form the surface layers constituents. The results obtained so INAA far point to: (1) the existence of three main chemical-based clusters; and (2) a general attribution of the Chemical composition porcelains studied to southern China kilns; (3) a few samples are specifically attributed to Jingdezhen Ming dynasty and Zhangzhou kiln sites. -

Natalia Khlebtsevich

Natalia Khlebtsevich https://www.khlebtsevich.com/ https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100003401203572 https://www.instagram.com/khlebtsevich_natalia/ [email protected] +7 916 141 84 93 Born in Moscow 1971. Graduated from Stroganov Moscow State University of Industrial and Applied Arts (1990-1996, Department of Ceramics), with postgraduate studies in art history in the same school (1998- 2000). Member of the Moscow Union of Artists, International Artist Federation, International Academy of Ceramics IAC, Professor of the Stroganov University. Starting 1993 constantly participated in Russian and International exhibitions. Many of Natalia Khlebtsevich's installations are marked by the presence of biological components. The primary media of her work are clay and porcelain which, by way of firing, become permanently unchangeable, thus signifying the irrevocable terminality. Juxtaposed to this nominal timelessness, the biological, obviously mortal parts stand as contrapuntal elements embodying life and growth, constantly changing the visual perception of the objects. Some of the installations include light and water and soundtracks epitomizing the passage of time. The work is not in a state of standstill, the accompanying living things and recorded sounds induce the viewers in the process of its creation engaging them to participate in artist’s exploration of human condition and the perception of time. Prizes: • Laureate. International Ceramics Festival. Gzhel. Russia.2018 • Honorable Mention of the Jury. 39th International Ceramics Competition in Gualdo Tadino (Italy). 2017. • Honorable Mention of the Jury. 2017.11 MINO Ceramics Festival (Japan). • Nominee. Kandinsky Prize. 2009 и 2011. Breus Foundation. • Laureate of Young Artist Show 2004. Moscow Union of Artists. • Laureate. International Festival of Archtecture and Design. -

Views of a Porcelain 15

THE INFLUENCE OF GLASS TECHNOLOGY vessels nor to ceramic figurines, but to beads made in imitation of imported glass.10 The original models were ON CHINESE CERAMICS eye-beads of a style produced at numerous sites around the Mediterranean, in Central Asia and also in southern Russia, and current in the Near East since about 1500 Nigel Wood BC.11 A few polychrome glass beads found their way to Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford. China in the later Bronze Age, including one example excavated from a Spring and Autumn period (770-476 BC) site in Henan province.12 This particular blue and ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT AND ENDURING DIFFER- white eye bead was of a style current in the eastern ences between the ceramics of China and the Near East Mediterranean in the 6th to 3rd century BC and proved lies in the role that glass has played in the establishment to have been coloured by such sophisticated, but of their respective ceramic traditions. In the ceramics of typically Near Eastern, chromophores as calcium- Mesopotamia, Persia, Egypt, and Syria glass technology antimonate-white, cobalt-blue and a copper-turquoise, proved vital for the development of glazed ceramics. while its glass was of the soda-lime type, common in 13 Figure 2. Earthenware jar with weathered glazes. Warring States Following the appearance of glazed stone-based the ancient world. period. Probably 3rd century BC (height: 9.5 cm). The British ceramics in the fourth millennium BC, the first glazes These ‘western’ beads would have been wonders in Museum. -

Industrial Heritage, Tourism and Old Industrial Buildings: Charting the Difficult Path from Redundancy to Heritage Attraction

RESEARCH Cutting Edge 1997 Industrial heritage, tourism and old industrial buildings: charting the difficult path from redundancy to heritage attraction Rick Ball, Staffordshire University ISBN 0-85406-864-3 INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE, TOURISM AND OLD INDUSTRIAL BUILDINGS: CHARTING THE DIFFICULT PATH FROM REDUNDANCY TO HERITAGE ATTRACTION Dr. Rick Ball Division of Geography Staffordshire University Leek Road Stoke-on-Trent ST4 2DF UK Abstract This exploratory paper considers the processes, problems and constraints involved in the transition of old industrial buildings, often those prone to vacancy, into heritage and tourism- linked uses. It discusses the heritage-property nexus with regard to industrial buildings, and builds an empirical picture of such relationships in a specific local property arena. The discussion is partly based on research projects completed in a number of localities within the British West Midlands. In particular, it draws on work on the evaluation of European Commission Community Initiatives in the West Midlands that have targetted tourism development, as well as on EPSRC funded research focused on vacant industrial buildings in Stoke-on-Trent. As such, in scene-setting style, a structure is developed for the evaluation of heritage-property links with the emphasis on the small number of specific local projects that have at least partly sought to bring buildings back into use with some, perhaps extensive, degree of heritage activity in mind. 1. Heritage and the property domain - some introductory comments The background to this paper is the apparent reassertion of industrial heritage as a flavour of tourism in the late 1990s (Goodall, 1996), a process pursued with vigour in the quest for the renaissance of the urban industrial economy (see Ball and Stobart, 1996). -

The Museum in the City

01 / 2019 ISSN 2520-2472 MUSEUMUSEUMMSS OFOF CITIESCITIES REVIEW REVIEW network.icom.museum/camoc/ Towards the ICOM Kyoto 2019: Get to know the museums of Osaka COnferenCe and GuIde relaTed TO MuseuMs 1 MUSEUMS OF CONTENTS CITIES REVIEW 25 18 21 04 15 08 03 Genk. Engaging with heritage Joana Sousa Monteiro Osaka 04 18 30 City in the Museum / - Introductory note: Museum Since 1918 Museum in the City Countdown to ICOM Kyoto 2019! 21 32 - History of Museum in Osaka: Overview of the development of Osaka city “Maximising the impact of Towards a City Museum and its museums cultural heritage on local Watch - The Museum of development” – Oriental Ceramics Osaka an OECD conference and 33 and the Nakanoshima guide related to From The Museum museums of the City for a Museum of the City 23 34 Culture: Considering the Quantum Culture: The future of museums is plural 38 Future conferences of a Natural History Museum 25 - Towards Conceptualizing A Post-Industrial Walk in Cover Photo: osaka Castle. © en.wikipedia.org Editorial Board: 2 From the Chair The ICOM General Conference happens every three 2019. Historic House Museums. Now that the deadline for the call for papers has is organizing the workshop “Towards a City Museum rd and 4th got the highest number of abstract proposals ever: ICOM Portugal and the Museum of Lisbon. The workshop intends to discuss and set up glad to know that so many good professionals are interested in our work. worldwide. The invited speakers for the workshop are As a learning tool about Japanese museums and museums of Osaka with an assessment of the History of Barcelona and European City Museums by Shugo Kato from the Osaka Museum of History. -

Antiques & Fine

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester Director Shuttleworth Director Director Antiques & Fine Art Auction Tuesday 4th August 2020 at 10.00 Viewing on a rota basis by appointment only Special Auction Services Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL (Sat Nav tip - behind SPX Flow RG14 5TR) Telephone: 01635 580595 Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Harriet Mustard Helen Bennett Antiques & Antiques & Fine Art Fine Art Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price 1. A 1921 Sotheby’s 9. A small group of 19th Century 19. A 20th Century Dunhill lighter, auction catalogue, for ‘the official and later candlestick holders, including the base marked with model numbers, correspondence of General Robert two pairs, one brass and copper pair Dunhill London and Made in Switzerland, Monckton during his service in North dating to the mid 19th Century in the 6.5cm x 2.5cm America 1752-1763, and a few oil classical revival style, height 13.5cm (5+) £50-100 paintings by Benjamin West he property £30-50 of George Edwards Monckton’ 10th 20. A Chinese lacquer tray, with February 1921 10. A small quantity of Middle confronting dragons chasing the flaming £30-50 Eastern metal ware, including a pair pearl, 58cm x 37cm a/f of copper bowls with repousse floral £50-100 2. -

Clubhouse Network Newsletter Issue

PLEASE Clubhouse Network TAKE ONE Newsletter THEY’RE FREE Hello everyone, this is the twenty-first edition of the Clubhouse Network Newsletter made by volunteers and customers of the Clubhouse Community. Thanks to everyone who made contributions to this issue. We welcome any articles or ideas from Clubhouse customers. Chinese New Year celebrations took place at the City Museum and Art Gallery on 10th February. Members went along and joined in the fun. Things to enjoy included the dancing Chinese dragon, fire- crackers, traditional music, and a children’s theatre. Dragons are of course legendary animals, but they are important to Chinese people who think of dragons as helpful, friendly creatures. They are linked to good luck, long life and wisdom. The Dragon in the dance has features of other animals such as the horns of a stag, the scales of a fish Music, craft and mask making were being and the footpads of a tiger. demonstrated by talented artisans and musicians. Have fun with this Sudoku Puzzle! 2 Recovery Assistance Dogs This month Sasha talks about her life as Vicky’s assistance dog: I am Sasha and I am a Jack Russell cross and I am nine years old. I help my owner Vicky with getting out of our home. When we are together I help my owner to not panic going out to Clubhouse or mixing with people. My owner struggles with depression and anxiety and when together I help keep her calm. I’ll soon have passed my Level 1 ‘paw test’ so I can go to many more places. -

Robert Plot (1641—1696)

( 218 ) SOME EARLY BRITISH ORNITHOLOGISTS AND THEIR WORKS. BY W. H. MULLENS, SI.A., LL.M., M.B.O.U. V.—ROBERT PLOT (1641—1696) AND SOME EARLY COUNTY NATURAL HISTORIES. IN the year 1661, Joshua Childrey (1623—1670), antiquary, schoolmaster, and divine, published in London a small duodecimo work entitled " Britannia Baconia: / or, the Natural / Rarities / of / England, Scotland, & Wales." This book, although of no particular value in itself, being merely a brief and somewhat imperfect compilation, was nevertheless destined to be of some considerable influence on the literature of natural history in this country. For, according to Wood's " Athense Oxonienses" (p. 339), it inspired Robert Plot (1641—1696), the first keeper of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, with the idea of writing the " Natural History of Oxfordshire," which appeared in 1677, and which was followed in 1686 by a " Natural History of Staffordshire," the work of the same author ; who is said to have also contemplated similar histories of Middlesex and Kent. These two works of Robert Plot's also proved in their turn to be the forerunners of a numerous series of county natural histories by different writers. The full title of the " Natural History of Oxfordshire" is as follows :— " The / Natural History / of / Oxford-shire, / being an Essay toward the Natural History / of / England. / By R.P., LL.D. / [quotation from Arat. in Phsenom.] / [engraving] Printed at the Theater in Oxford, and are to be had there: / And in London at Mr. S. Millers, at the Star near the / West-end of SOME EARLY BRITISH ORNITHOLOGISTS. -

9. Ceramic Arts

Profile No.: 38 NIC Code: 23933 CEREMIC ARTS 1. INTRODUCTION: Ceramic art is art made from ceramic materials, including clay. It may take forms including art ware, tile, figurines, sculpture, and tableware. Ceramic art is one of the arts, particularly the visual arts. Of these, it is one of the plastic arts. While some ceramics are considered fine art, some are considered to be decorative, industrial or applied art objects. Ceramics may also be considered artifacts in archaeology. Ceramic art can be made by one person or by a group of people. In a pottery or ceramic factory, a group of people design, manufacture and decorate the art ware. Products from a pottery are sometimes referred to as "art pottery".[1] In a one-person pottery studio, ceramists or potters produce studio pottery. Most traditional ceramic products were made from clay (or clay mixed with other materials), shaped and subjected to heat, and tableware and decorative ceramics are generally still made this way. In modern ceramic engineering usage, ceramics is the art and science of making objects from inorganic, non-metallic materials by the action of heat. It excludes glass and mosaic made from glass tesserae. There is a long history of ceramic art in almost all developed cultures, and often ceramic objects are all the artistic evidence left from vanished cultures. Elements of ceramic art, upon which different degrees of emphasis have been placed at different times, are the shape of the object, its decoration by painting, carving and other methods, and the glazing found on most ceramics. 2. -

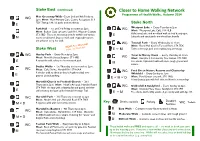

Closer to Home Walking Network

Stoke East (continued) Closer to Home Walking Network Programme of Health Walks, Autumn 2014 Meir Greenway Walk - Every 2nd and 4th Friday at WC 2pm Meet: Meir Primary Care Centre Reception, ST3 7DY Taking in Meir’s parks and woodlands. Stoke North E Westport Lake - Every Tuesday at 2pm Park Hall - 1st and 3rd Friday in month at 2pm WC Meet: Westport Lake Café, ST6 4LB Meet: Bolton Gate car park, Leek Rd., Weston Coyney, A flat canal, lake and woodland walk at local beauty spot. ST3 5BD This is an interesting area for wildlife and various E Lakeside and canal paths are wheelchair friendly. M routes are followed. Dogs on leads with responsible owners are welcome to try this walk. WC Tunstall Park - Every Wednesday at 11am Hartshill NEW! Four Meet: Floral Hall Café in Tunstall Park, ST6 7EX Stoke West walks on Thursdays E or M Takes in heritage park and neighbouring greenways. Hanley Park - Every Monday at 2pm WC WC Trent & Mersey Canal - Every Thursday at 11am Meet: Norfolk Street Surgery, ST1 4PB Meet: Sandyford Community Fire Station, ST6 5BX A canalside walk, taking in the renovated park. E M Free drinks. A pleasant walk with some rough ground and inclines. Stubbs Walks - 1st Thursday in the month at 2pm WC Meet: Cafe Divine, Hartshill Rd. ST4 6AA WC Ford Green Nature Reserve and Chatterley A circular walk of about an hour’s length on fairly level Whitfield - Every Sunday at 1pm E ground. Limited parking. E or M or D Meet: Ford Green car park, ST6 1NG A local beauty spot with hall, lake and historic surroundings. -

England's Biggest FREE Heritage Festival Chat Terl Ey

or by telephone. by or heritage festival heritage Please check details with individual sites before visiting through their websites websites their through visiting before sites individual with details check Please FREE provided. information the of accuracy the for liability no accept publishers the Whilst every effort has been made to ensure that the information is correct, correct, is information the that ensure to made been has effort every Whilst @heritageopenday facebook.com/heritageopendays stoke.gov.uk/heritage England’s biggest England’s information about local events go to to go events local about information www.heritageopendays.org.uk www.heritageopendays.org.uk or for more more for or To search the online directory of events go to to go events of directory online the search To www.stoke.gov/heritage by England Heritage. Heritage. England by ouncil 10002428. ouncil yC it tC ren Stoke-on-T reserved. rights All 2011. opyright nC row ©C Heritage Open Days National Partnership and funded funded and Partnership National Days Open Heritage On a national level, the programme is managed by the the by managed is programme the level, national a On M6 South M6 25 to support our application. our support to opportunity for people to see what we have on offer offer on have we what see to people for opportunity 21 Derby bid to become UK City of Culture 2021, what a great great a what 2021, Culture of City UK become to bid A520 To industrial revolution. This year the city will submit a a submit will city the year This revolution. -

Natural History of Staffordshire Printed in Oxford in 1686, the Subject of This Article

THE NATURAL HISTORY OF STAFFORD-SHIRE. By Robert Plot, LLD. Keeper of the Ashmolean Musæum and Professor of Chymistry in the University of Oxford. Ye shall Describe the Land, and bring the Description hither to Me. Joshua 8. v. 6. Oxford printed at the Theatre, Anno M. DC. LXXXVI. (1686) by Yasha Beresiner Introduction This volume, now in the Masonic Library of the Regular Grand Lodge of Italy, contains the earliest recorded account of accepted masonry and is considered the most implicit report on the fraternity available for the period at the end of the 17th century. It is printed in paragraphs 85 to 88 inclusive, on pages 316 to 318 of the tome. This text is referred to as the Plot Abstract. Its importance lies a) with regard to its content i.e. the summary of the legendary history, the description of contemporary freemasonry, and the criticisms of the fraternity and b) as to the sources from which Plot may have derived his information, most importantly, what he refers to as the ‘large parchment volum they have amongst them . .’ The purpose of this article is not to analyse the text and its content but rather to identify and clarify the reasons behind the importance of this Volume in the context of Masonic bibliography and history. Robert Plot Robert Plot (1640-96) was born in Kent and received a BA degree from Oxford University in 1661, an MA in 1664 and a Law degrees in 1671. In 1677 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and became Secretary in 1682.