Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Century of Scholarship 1881 – 2004

A Century of Scholarship 1881 – 2004 Distinguished Scholars Reception Program (Date – TBD) Preface A HUNDRED YEARS OF SCHOLARSHIP AND RESEARCH AT MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY DISTINGUISHED SCHOLARS’ RECEPTION (DATE – TBD) At today’s reception we celebrate the outstanding accomplishments, excluding scholarship and creativity of Marquette remarkable records in many non-scholarly faculty, staff and alumni throughout the pursuits. It is noted that the careers of last century, and we eagerly anticipate the some alumni have been recognized more coming century. From what you read in fully over the years through various this booklet, who can imagine the scope Alumni Association awards. and importance of the work Marquette people will do during the coming hundred Given limitations, it is likely that some years? deserving individuals have been omitted and others have incomplete or incorrect In addition, this gathering honors the citations in the program listing. Apologies recipient of the Lawrence G. Haggerty are extended to anyone whose work has Faculty Award for Research Excellence, not been properly recognized; just as as well as recognizing the prestigious prize scholarship is a work always in progress, and the man for whom it is named. so is the compilation of a list like the one Presented for the first time in the year that follows. To improve the 2000, the award has come to be regarded completeness and correctness of the as a distinguishing mark of faculty listing, you are invited to submit to the excellence in research and scholarship. Graduate School the names of individuals and titles of works and honors that have This program lists much of the published been omitted or wrongly cited so that scholarship, grant awards, and major additions and changes can be made to the honors and distinctions among database. -

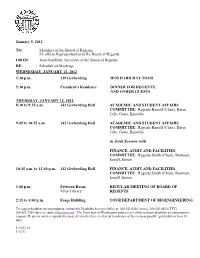

In Joint Session With

January 5, 2012 TO: Members of the Board of Regents Ex officio Representatives to the Board of Regents FROM: Joan Goldblatt, Secretary of the Board of Regents RE: Schedule of Meetings WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 11, 2012 3:30 p.m. 139 Gerberding HUB HARD HAT TOUR 5:30 p.m. President’s Residence DINNER FOR REGENTS, AND OTHER GUESTS THURSDAY, JANUARY 12, 2012 8:30 to 9:35 a.m. 142 Gerberding Hall ACADEMIC AND STUDENT AFFAIRS COMMITTEE: Regents Harrell (Chair), Barer, Cole, Gates, Knowles 9:45 to 10:35 a.m. 142 Gerberding Hall ACADEMIC AND STUDENT AFFAIRS COMMITTEE: Regents Harrell (Chair), Barer, Cole, Gates, Knowles in Joint Session with FINANCE, AUDIT AND FACILITIES COMMITTEE: Regents Smith (Chair), Brotman, Jewell, Simon 10:45 a.m. to 12:40 p.m. 142 Gerberding Hall FINANCE, AUDIT AND FACILITIES COMMITTEE: Regents Smith (Chair), Brotman, Jewell, Simon 1:00 p.m. Petersen Room REGULAR MEETING OF BOARD OF Allen Library REGENTS 2:15 to 4:00 p.m. Foege Building TOUR DEPARTMENT OF BIOENGINEERING To request disability accommodation, contact the Disability Services Office at: 206.543.6450 (voice), 206.543.6452 (TTY), 206.685.7264 (fax), or email at [email protected]. The University of Washington makes every effort to honor disability accommodation requests. Requests can be responded to most effectively if received as far in advance of the event as possible, preferably at least 10 days. 1.1/201-12 1/12/12 UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON BOARD OF REGENTS Academic and Student Affairs Committee Regents Harrell (Chair), Barer, Cole, Gates, Knowles January 12, 2012 8:30 to 9:35 a.m. -

University of Washington Special Collections

UNIVERSITY CHRONOLOGY 1850 to 1859 February 28, 1854 Governor Isaac Ingalls Stevens recommended to the first territorial legislature a memorial to Congress for the grant of two townships of land for the endowment for a university. (“That every youth, however limited his opportunities, find his place in the school, the college, the university, if God has given him the necessary gifts.” Governor Stevens) March 22, 1854 Memorial to Congress passed by the legislature. January 29, 1855 Legislature established two universities, one in Lewis County and one in Seattle. January 30, 1858 Legislature repealed act of 1855 and located one university at Cowlitz Farm Prairies, Lewis County, provided one hundred and sixty acres be locally donated for a campus. (The condition was never met.) 1860 to 1869 December 12, 1860 Legislature passed bill relocating the university at Seattle on condition ten acres be donated for a suitable campus. January 21, 1861 Legislative act was passed providing for the selection and location of endowment lands reserved for university purposes, and for the appointment of commissioners for the selection of a site for the territorial university. February 22, 1861 Commissioners first met. “Father” Daniel Bagley was chosen president of the board April 16, 1861 Arthur A. Denny, Edward Lander, and Charles C. Terry deeded the necessary ten acres for the campus. (This campus was occupied be the University until 1894.) May 21, 1861 Corner stone of first territorial University building was laid. “The finest educational structure in Pacific Northwest.” November 4, 1861 The University opened, with Asa Shinn Mercer as temporary head. Accommodations: one room and thirty students. -

Road & Track Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8j38wwz No online items Guide to the Road & Track Magazine Records M1919 David Krah, Beaudry Allen, Kendra Tsai, Gurudarshan Khalsa Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2015 ; revised 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Road & Track M1919 1 Magazine Records M1919 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Road & Track Magazine records creator: Road & Track magazine Identifier/Call Number: M1919 Physical Description: 485 Linear Feet(1162 containers) Date (inclusive): circa 1920-2012 Language of Material: The materials are primarily in English with small amounts of material in German, French and Italian and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Abstract: The records of Road & Track magazine consist primarily of subject files, arranged by make and model of vehicle, as well as material on performance and comparison testing and racing. Conditions Governing Use While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use in research, teaching, and private study. Any transmission or reproduction beyond that allowed by fair use requires permission from the owners of rights, heir(s) or assigns. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Road & Track Magazine records (M1919). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. Note that material must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. -

Zubehör Für Opel Design Mit Zukunft

2020 / 2021 ZUBEHÖR FÜR OPEL DESIGN MIT ZUKUNFT DESIGN KOMFORT INFOTAINMENT SICHERHEIT TRANSPORT PFLEGE E-MOBILITÄT EDITORIAL HERZLICH WILLKOMMEN IN IHREM AUTOHAUS! Die Zukunft fährt vor: auch in unserem Autohaus. Immer mehr Kunden interessieren sich neben den beliebten Opel-Modellen mit ihren gleichermaßen kraftvollen wie effizienten Verbrennungsmotoren für Fahrzeuge mit Hybrid- oder Elektroantrieb. Und diesbezüglich wird die Auswahl immer größer: Ab 2021 laden 8 elektrifizierte Opel-Modelle dazu ein, in die Zukunft der Mobilität durchzustarten. Ein Grund mehr, warum wir auch unser umfangreiches Zubehör- und Ausstattungs-Programm erweitert haben. Neben einer großen Auswahl an 100%ig auf Ihren Opel abgestimmten Artikeln, finden Sie in unserem aktuellen Zubehörkatalog auf Seite 29 eine Vielzahl an Ladestationen für elektrifizierte Fahrzeuge. Aber egal für welches Antriebskonzept Sie sich auch entscheiden – oder bereits entschieden haben: In Sachen Wartungen, Reparaturen und Inspektionen bleiben wir unserem Anspruch auch in Zukunft treu. Unser hochqualifiziertes Werkstatt- und Service-Team ist jederzeit für Sie da und berät Sie gern rund um alle Belange Ihres Fahrzeuges. Das gilt natürlich auch für die Angebote unseres Kataloges. Sollten Sie beim Stöbern zu ausgewählten Artikeln Fragen haben, stehen wir Ihnen jederzeit gerne persönlich beratend zur Seite. Viel Spaß beim Lesen wünscht Ihr Autohaus-Team EDITORIAL 3 Marderschutz ab Seite 50 Beleuchtung ab Seite 44 Autoradios u. Soundsysteme Navigationsgeräte u. Seite 41 + 43 Freisprecheinrichtungen -

Anniversary Dates 2020 Audi Tradition 2 Anniversary Dates 2020

Audi Tradition Anniversary Dates 2020 Audi Tradition 2 Anniversary Dates 2020 Contents Anniversaries in Our Corporate History May 2005 Body in the Manufacture of Production Cars ..........12 15 Years Audi Forum Neckarsulm ............................5 March 1980 December 2000 40 Years Audi quattro ...........................................13 20 Years Audi Forum Ingolstadt .............................6 October 1975 September 1995 45 Years Audi GTE Engine .....................................14 25 Years Audi TT and TTS .......................................7 November 1975 March 1990 45 Years Start of Porsche 924 Production 30 Years Audi Duo Hybrid Vehicles ...........................8 in Neckarsulm ......................................................15 September 1990 July 1970 30 Years Audi S2 Coupé ..........................................9 50 Years Market Launch of Audi 100 Coupé S .........16 December 1990 1970 30 Years Audi 100 C4 / 50 Years Start-Up Audi’s First Six-Cylinder Engine .............................10 of Technical Development ....................................17 January 1985 March / April 1965 35 Years Renaming of Audi NSU 55 Years End of Production of DKW F 11, Auto Union AG as AUDI AG ...................................11 DKW F 12, AU 1000 Sp ........................................18 September 1985 September 1965 35 Years Audi Introduced the Fully Galvanized 55 Years NSU Prinz 1000 TT & NSU Typ 110 ..........19 Audi Tradition 3 Anniversary Dates 2020 Continued Anniversaries in Our Corporate History April 1940 -

Allgemeine Betriebserlaubnis Unbedingt Im Fahrzeug Mitführen!

Allgemeine Betriebserlaubnis Unbedingt im Fahrzeug mitführen! Nachdruck und jegliche Art der Vervielfältigung dieser ABE, auch auszugsweise, sind untersagt. Zuwiderhandlungen werden gerichtlich verfolgt. Diese ABE ist in den Kfz-Papieren mitzuführen und bei Fahrzeugkontrollen auf Verlangen vorzuzeigen. Ein Eintrag in die Fahrzeugpapiere ist nicht erforderlich. Automobilbau GmbH & Co. KG D-73630 Remshalden • Tel.: 07151/971-300 • Fax.: 07151/971-305 1001 / Stand 09.13 Chevrolet: Es müssen die Radmuttern der Serien-Leichtmetallräder des Fahrzeugherstellers verwendet werden! The wheel nut of the series-light-alloy wheel of the vehicle manufacturer has to be used! Chevrolet-Nr.: Cruze / Orlando : 09594682 / Captiva : 94 837 389 Irmscher Sonderrad 7 61 10 612 8J x 18 ET40; 115/ 5-L Turbo-Star, Schwarz matt Kraftfahrt-Bundesamt DE-24932 Flensburg ALLGEMEINE BETRIEBSERLAUBNIS (ABE) nach § 22 in Verbindung mit § 20 Straßenverkehrs-Zulassungs-Ordnung (StVZO) in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 26.04.2012 (BGBl I S.679) Nummer der ABE: 48734*03 Gerät: Sonderräder für Personenkraftwagen 8 J x 18 H2 Typ: 700 61 10 002 Inhaber der ABE Irmscher Automobilbau GmbH & Co. KG und Hersteller: DE-73630 Remshalden Für die obenbezeichneten reihenweise zu fertigenden oder gefertigten Geräte wird dieser Nachtrag mit folgender Maßgabe erteilt: Die sich aus der Allgemeinen Betriebserlaubnis ergebenden Pflichten gelten sinngemäß auch für den Nachtrag. In den bisherigen Genehmigungsunterlagen treten die aus diesem Nachtrag ersichtlichen Änderungen bzw. Ergänzungen ein. Kraftfahrt-Bundesamt DE-24932 Flensburg 2 Nummer der ABE: 48734*03 Die ABE-Nr. 48734 erstreckt sich nunmehr auf die Sonderräder 8 J x 18 H2 , Typ 700 61 10 002, in den Ausführungen wie im Nachtragsgutachten Nr. -

Diversity Without Integration Kevin Woodson University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2016 Diversity Without Integration Kevin Woodson University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Education Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Woodson, Diversity Without Integration, 120 Penn State L. Rev. 807 (2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diversity Without Integration Kevin Woodson* Abstract The de facto racial segregation pervasive at colleges and universities across the country undermines a necessary precondition for the diversity benefits embraced by the Court in Grutter-therequirement that students partake in high-quality interracial interactions and social relationships with one another. This disjuncture between Grutter's vision of universities as sites of robust cross-racial exchange and the reality of racial separation should be of great concern, not just because of its potential constitutional implications for affirmative action but also because it reifies racial hierarchy and reinforces inequality. Drawing from an extensive body of social science research, this article explains that the failure of schools to achieve greater racial integration in campus life perpetuates harmful racial biases and exacerbates racial disparities in social capital, to the disadvantage of black Americans. After providing an overview of de facto racial segregation at America's colleges and making clear its considerable long-term costs, this article calls for universities to modify certain institutional policies, practices, and arrangements that facilitate and sustain racial separation on campus. -

Sept October 2010.Pub

30th Volume 30, Issue 5 Se Anniversary The BIG Blitz Index OMCOMC Blitz President’sIndex 1985-2010 Message Inside this issue: ptember/October 2010Inside this issue: 1985-2010 Welcome to the Opel Motorsport Club THE OPEL MOTORSPORT CLUB IS CELEBRATING ITS 30TH YEAR OF DEDICATION TO THE PRESERVATION AND APPRECIATION OF ALL GERMAN OPELS, WITH SPECIAL EMPHASIS ON MODELS IMPORTED INTO THE UNITED STATES. WE ARE HEADQUARTERED IN THE LOS ANGELES AREA, AND HAVE CHAPTERS ACROSS THE COUNTRY, IN EUROPE AND IN CANADA. MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS INCLUDE SUBSCRIPTION TO OUR NEWSLETTER, THE BLITZ, LISTINGS FOR PARTS AND SERVICE SUPPLIERS, BLITZ INDEX AND TECH TIP INDEX (1985-DATE), FREE CLASSIFIED ADS (3 PER YEAR), CLUB ITEMS, OWNER SUPPORT AND ACTIVITIES, INCLUDING MEETINGS AND OUR ANNUAL PICNIC AND CAR SHOW. The Club Regional Chapters The Blitz TO APPLY FOR MEMBERSHIP European Chapter (Netherlands) SEND EVENT INFORMATION, TECH CONTACT: Contact Louis van Steen: (011 31) 297 340 TIPS, PARTS INFORMATION, LETTERS, OMC TREASURER, c/o Dick Counsil 536 (please take note of the time zone CHAPTER ACTIVITY ANNOUNCEMENTS, 3824 Franklin Street before calling), fast60gt (at) yahoo.com ADVERTISEMENTS AND ALL OTHER ITEMS OF INTEREST TO: La Crescenta, CA 91214-1607 Florida Chapter (Coral Gables, FL) Opel BLITZ Editor Contact John Malone: 305-443-8513 P.O Box 4004 MEMBERSHIP DUES: Michigan Chapter Sonora, CA 95370-4004 USA Regular: $45 Annually via Checks and Contact John Brooks: 616-233-9050 ext 12 Deadline: (At Discretion of OMC Editor) Money Orders (US funds only, made payable to Opel Motorsport Club) or $47 Johncinquo (at) hotmail.com. -

New Prospects Paul Horn Hall Completes Stuttgart Trade Fair Centre

MessageTRADE FAIRS | CONGRESSES | EVENTS 01 | 2018 New prospects Paul Horn Hall completes Stuttgart Trade Fair Centre RETRO CLASSICS 50 years CMT R+T World record Trade fair classic Expert advice on the Fildern celebrates anniversary at first hand 1 2 3 Ludwigsburg Residential Palace Solitude Palace The Sepulchral Chapel on Württemberg Hill ASTONISHINGLY BEAUTIFUL! Our palaces are full of surprises. Discover the region‘s living history. 60 of the most beautiful fascinating stories from times gone by – it‘s time to make a very palaces, monasteries, gardens and castles in Baden-Württem- special journey of discovery in and around Stuttgart. For more berg await your visit. Splendid sights, diverse experiences and details visit: www.schloesser - und - gaerten.de/en SSG / LMZ: Titel Niels Schubert; 1, 2, 3 Achim Mende // // Mende Schubert; 1, 2, 3 Achim Niels Titel LMZ: / SSG BILDNACHWEIS Designkonzept: www.jungkommunikation.de Designkonzept: CONTENTS 1 2 3 Ludwigsburg Residential Palace Solitude Palace The Sepulchral Chapel on Württemberg Hill NEWS – TRENDS 04 Sustainability as a corporate strategy Messe Stuttgart documents the specific measures ASTONISHINGLY 05 Editorial ”Urgently required” BEAUTIFUL! COVER STORY 08 New prospects The new Paul Horn Hall completes the Stuttgart Our palaces are full of surprises. Trade Fair Centre on time for CMT 2018 Discover the region‘s living history. 60 of the most beautiful fascinating stories from times gone by – it‘s time to make a very LOCATION STUTTGART palaces, monasteries, gardens and castles in Baden-Württem- special journey of discovery in and around Stuttgart. For more 16 Leading position in terms of economic performance berg await your visit. -

PHI GAMMA DELTA Riguing New Jew • I Ry and Fine Gifts Are Billed with an Exciting Array of Balfour Parade Favorites to Make the 1946 Editit NOVEMBER, 1945 No

E PHI MM E.' LTA The Salt of Bataan Into Their Wounds Major-General Charles A. Willough-by (Gettysburg '14) Enters Manila Conference Room With Japanese Lieutenant- General Torashiro Kawabe PRESENTING I ff f 1 9 4 6 F. r) r T PHI GAMMA DELTA We HE BALFOUR (Registered U. S. Patent Office) BLUE BOOK A MAGAZINE PUBLISHED CONTINUOUSLY SINCE 1879 BY THE FRATERNITY OP PHI GAMMA DELTA Jut riguing new jew • I ry and fine gifts are billed with an exciting array of Balfour Parade favorites to make the 1946 editit NOVEMBER, 1945 No. 2 the BALFOUli BLUE BOOK the fine,1 Just a few of the many TABLE OF CONTENTS interesting things you will find .. Our War Story—Continued 99 121 Here you will find forty pages of .13:: An Editor Reaches His Anecdotage The NEW 1946 139 edition quality fraternity jewelry: Beautiful rh: The Fraternity His Hobby-Horse 143 BALFOUR BLUE BOOK •(,e the new Identification Ring! — finel Fame's Accolade for 59 Brothers lets, pendants, lockets, chapter weddinit In a Snug Little Nook by the Fireside 147 service billfolds, writing portfolios, Fratres Qui Fuerunt Sed Nunc Ad Astra 152 ery, place cards, honor rolls and schar Gleams of White Star Dust 156 Doing Double Duty scrolls. Fijis Here, There and Everywhere 159 165 Mail post card for Fijis As Press Sees Them 167 FAeTt)RY is proud of Chapter Days—and Nights YOUR FREE COPY! UR 191 O the part it has played dur- This issue as the Editor Sees It ing the war years in the fur- nishing of vital war materials COMPLETE BALF01 1: for the protection and aid of SERVICE the men in the armed forces. -

Eight Secrets of Beijing Snapshots of a 3,000 Year-Old City

Barco company magazine • Volume 3 • Issue 6 magazine Eight secrets of Beijing Snapshots of a 3,000 year-old city Future past 10 accurate predictions from science fiction Tablet truths Can tablet PCs make it in healthcare? 1 redefine_issue_6c.indd 1 2/05/11 11:50 6 Eight secrets of beijing 24 million 735,000 Science pixels visitors Beauty is in the 1. 2. 3. Wireless communication Immersive 3D video conferencing It all just fits. Science fiction is notorious for its continuous attempts to make First mention: First mention: First mention: 1923, in H.G. Wells’s ‘Men like 1889, in Jules Verne’s ‘The Year 2889’ of the operator predictions about future technology. Even if it isn’t the central theme 1956, in Arthur C. Clarke’s ‘The City and the Stars’ Full display roll-out The enclosure for example, Gods’ 30 combines low weight, sealing, of its stories, it’s always involved on the side. And sometimes, it also Clarke described an immersive 3D setup in terms of gaming, and said: “You Video communication was and still is While the description in the common in science fiction, but its first at the Geneva Motor Show inspires scientists to make new technology breakthroughs. were an active participant and possessed—or seemed to possess—free will. booths low cost, noise damping, novel is fairly clunky, Wells The events […] might have been prepared beforehand, but there was enough mention predated the commercially made it clear that his characters flexibility to allow for wide variation.” Since the late 1980s, immersive 3D viable technology by nearly a century.