The Black Power Movement and the Black Student Union (Bsu)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

“The Negroes’ Temporary Farewell” JIM CROW AND THE EXCLUSION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS FROM CONGRESS, 1887–1929 On December 5, 1887, for the first time in almost two decades, Congress convened without an African-American Member. “All the men who stood up in awkward squads to be sworn in on Monday had white faces,” noted a correspondent for the Philadelphia Record of the Members who took the oath of office on the House Floor. “The negro is not only out of Congress, he is practically out of politics.”1 Though three black men served in the next Congress (51st, 1889–1891), the number of African Americans serving on Capitol Hill diminished significantly as the congressional focus on racial equality faded. Only five African Americans were elected to the House in the next decade: Henry Cheatham and George White of North Carolina, Thomas Miller and George Murray of South Carolina, and John M. Langston of Virginia. But despite their isolation, these men sought to represent the interests of all African Americans. Like their predecessors, they confronted violent and contested elections, difficulty procuring desirable committee assignments, and an inability to pass their legislative initiatives. Moreover, these black Members faced further impediments in the form of legalized segregation and disfranchisement, general disinterest in progressive racial legislation, and the increasing power of southern conservatives in Congress. John M. Langston took his seat in Congress after contesting the election results in his district. One of the first African Americans in the nation elected to public office, he was clerk of the Brownhelm (Ohio) Townshipn i 1855. -

The Power to Say Who's Human

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Africana Studies Honors College 5-2012 The Power to Say Who’s Human: Politics of Dehumanization in the Four-Hundred-Year War between the White Supremacist Caste System and Afrocentrism Sam Chernikoff Frunkin University at Albany, State University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_africana Part of the African Studies Commons Recommended Citation Frunkin, Sam Chernikoff, "The Power to Say Who’s Human: Politics of Dehumanization in the Four- Hundred-Year War between the White Supremacist Caste System and Afrocentrism" (2012). Africana Studies. 1. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_africana/1 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Power to Say Who’s Human The Power to Say Who’s Human: Politics of Dehumanization in the Four-Hundred-Year War between the White Supremacist Caste System and Afrocentrism Sam Chernikoff Frumkin Africana Studies Department University at Albany Spring 2012 1 The Power to Say Who’s Human —Introduction — Race represents an intricate paradox in modern day America. No one can dispute the extraordinary progress that was made in the fifty years between the de jure segregation of Jim Crow, and President Barack Obama’s inauguration. However, it is equally absurd to refute the prominence of institutionalized racism in today’s society. America remains a nation of haves and have-nots and, unfortunately, race continues to be a reliable predictor of who belongs in each category. -

How Did the Civil Rights Movement Impact the Lives of African Americans?

Grade 4: Unit 6 How did the Civil Rights Movement impact the lives of African Americans? This instructional task engages students in content related to the following grade-level expectations: • 4.1.41 Produce clear and coherent writing to: o compare and contrast past and present viewpoints on a given historical topic o conduct simple research summarize actions/events and explain significance Content o o differentiate between the 5 regions of the United States • 4.1.7 Summarize primary resources and explain their historical importance • 4.7.1 Identify and summarize significant changes that have been made to the United States Constitution through the amendment process • 4.8.4 Explain how good citizenship can solve a current issue This instructional task asks students to explain the impact of the Civil Rights Movement on African Claims Americans. This instructional task helps students explore and develop claims around the content from unit 6: Unit Connection • How can good citizenship solve a current issue? (4.8.4) Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task 1 Performance Task 2 Performance Task 3 Performance Task 4 How did the 14th What role did Plessy v. What impacts did civic How did Civil Rights Amendment guarantee Ferguson and Brown v. leaders and citizens have legislation affect the Supporting Questions equal rights to U.S. Board of Education on desegregation? lives of African citizens? impact segregation Americans? practices? Students will analyze Students will compare Students will explore how Students will the 14th Amendment to and contrast the citizens’ and civic leaders’ determine the impact determine how the impacts that Plessy v. -

The Limits of “Diversity” Where Affirmative Action Was About Compensatory Justice, Diversity Is Meant to Be a Shared Benefit

The Limits of “Diversity” Where affirmative action was about compensatory justice, diversity is meant to be a shared benefit. But does the rationale carry weight? By Kelefa Sanneh, THE NEW YORKER, October 9, 2017 This summer, the Times reported that, under President Trump, the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice had acquired a new focus. The division, which was founded in 1957, during the fight over school integration, would now be going after colleges for discriminating against white applicants. The article cited an internal memo soliciting staff lawyers for “investigations and possible litigation related to intentional race-based discrimination in college and university admissions.” But the memo did not explicitly mention white students, and a spokesperson for the Justice Department charged that the story was inaccurate. She said that the request for lawyers related specifically to a complaint from 2015, when a number of groups charged that Harvard was discriminating against Asian-American students. In one sense, Asian-Americans were overrepresented at Harvard: in 2013, they made up eighteen per cent of undergraduates, despite being only about five per cent of the country’s population. But at the California Institute of Technology, which does not employ racial preferences, Asian- Americans made up forty-three per cent of undergraduates—a figure that had increased by more than half over the previous two decades, while Harvard’s percentage had remained relatively flat. The plaintiffs used SAT scores and other data to argue that administrators had made it “far more difficult for Asian-Americans than for any other racial and ethnic group of students to gain admission to Harvard.” They claimed that Harvard, in its pursuit of racial parity, was not only rewarding black and Latino students but also penalizing Asian-American students—who were, after all, minorities, too. -

Untimely Meditations: Reflections on the Black Audio Film Collective

8QWLPHO\0HGLWDWLRQV5HIOHFWLRQVRQWKH%ODFN$XGLR )LOP&ROOHFWLYH .RGZR(VKXQ Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Number 19, Summer 2004, pp. 38-45 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\'XNH8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/nka/summary/v019/19.eshun.html Access provided by Birkbeck College-University of London (14 Mar 2015 12:24 GMT) t is no exaggeration to say that the installation of In its totality, the work of John Akomfrah, Reece Auguiste, Handsworth Songs (1985) at Documentall introduced a Edward George, Lina Gopaul, Avril Johnson, David Lawson, and new audience and a new generation to the work of the Trevor Mathison remains terra infirma. There are good reasons Black Audio Film Collective. An artworld audience internal and external to the group why this is so, and any sus• weaned on Fischli and Weiss emerged from the black tained exploration of the Collective's work should begin by iden• cube with a dramatically expanded sense of the historical, poet• tifying the reasons for that occlusion. Such an analysis in turn ic, and aesthetic project of the legendary British group. sets up the discursive parameters for a close hearing and viewing The critical acclaim that subsequently greeted Handsworth of the visionary project of the Black Audio Film Collective. Songs only underlines its reputation as the most important and We can locate the moment when the YBA narrative achieved influential art film to emerge from England in the last twenty cultural liftoff in 1996 with Douglas Gordon's Turner Prize vic• years. It is perhaps inevitable that Handsworth Songs has tended tory. -

A PSYCHOMETRIC EXAMINATION of the AFRICENTRIC SCALE Challenges in Measuring Afrocentric Values

10.1177/0021934704266596JOURNALCokley, Williams OF BLACK / A PSYCHOMETRIC STUDIES / JULY EXAMINATION 2005 ARTICLE A PSYCHOMETRIC EXAMINATION OF THE AFRICENTRIC SCALE Challenges in Measuring Afrocentric Values KEVIN COKLEY University of Missouri at Columbia WENDI WILLIAMS Georgia State University The articulation of an African-centered paradigm has increasingly become an important component of the social science research published on people of African descent. Although several instruments exist that operationalize different aspects of an Afrocentric philosophical paradigm, only one instru- ment, the Africentric Scale, explicitly operationalizes Afrocentric values using what is arguably the most commercial and accessible understanding of Afrocentricity, the seven principles of the Nguzu Saba. This study exam- ined the psychometric properties of the Africentric Scale with a sample of 167 African American students. Results of a factor analysis revealed that the Africentric Scale is best conceptualized as measuring a general di- mension of Afrocentrism rather than seven separate principles. The find- ings suggest that with continued research, the Africentric Scale will be an increasingly viable option among the handful of measures designed to assess some aspect of Afrocentric values, behavioral norms, and an African worldview. Keywords: African-centered psychology; Afrocentric cultural values For at least three decades, Black psychologists have devoted their lives to undo the racist and maleficent theory and practice of main- stream or European-centered psychological practice. Nobles (1986) succinctly surveys the work and conclusions of prominent European-centered psychologists and concludes that the European- centered approach to inquiry as well as the assumptions made con- JOURNAL OF BLACK STUDIES, Vol. 35 No. 6, July 2005 827-843 DOI: 10.1177/0021934704266596 © 2005 Sage Publications 827 828 JOURNAL OF BLACK STUDIES / JULY 2005 cerning people of African descent are inappropriate in understand- ing people of African descent. -

In Joint Session With

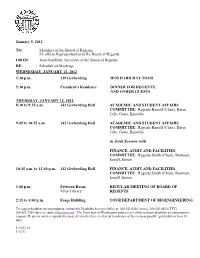

January 5, 2012 TO: Members of the Board of Regents Ex officio Representatives to the Board of Regents FROM: Joan Goldblatt, Secretary of the Board of Regents RE: Schedule of Meetings WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 11, 2012 3:30 p.m. 139 Gerberding HUB HARD HAT TOUR 5:30 p.m. President’s Residence DINNER FOR REGENTS, AND OTHER GUESTS THURSDAY, JANUARY 12, 2012 8:30 to 9:35 a.m. 142 Gerberding Hall ACADEMIC AND STUDENT AFFAIRS COMMITTEE: Regents Harrell (Chair), Barer, Cole, Gates, Knowles 9:45 to 10:35 a.m. 142 Gerberding Hall ACADEMIC AND STUDENT AFFAIRS COMMITTEE: Regents Harrell (Chair), Barer, Cole, Gates, Knowles in Joint Session with FINANCE, AUDIT AND FACILITIES COMMITTEE: Regents Smith (Chair), Brotman, Jewell, Simon 10:45 a.m. to 12:40 p.m. 142 Gerberding Hall FINANCE, AUDIT AND FACILITIES COMMITTEE: Regents Smith (Chair), Brotman, Jewell, Simon 1:00 p.m. Petersen Room REGULAR MEETING OF BOARD OF Allen Library REGENTS 2:15 to 4:00 p.m. Foege Building TOUR DEPARTMENT OF BIOENGINEERING To request disability accommodation, contact the Disability Services Office at: 206.543.6450 (voice), 206.543.6452 (TTY), 206.685.7264 (fax), or email at [email protected]. The University of Washington makes every effort to honor disability accommodation requests. Requests can be responded to most effectively if received as far in advance of the event as possible, preferably at least 10 days. 1.1/201-12 1/12/12 UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON BOARD OF REGENTS Academic and Student Affairs Committee Regents Harrell (Chair), Barer, Cole, Gates, Knowles January 12, 2012 8:30 to 9:35 a.m. -

University of Washington Special Collections

UNIVERSITY CHRONOLOGY 1850 to 1859 February 28, 1854 Governor Isaac Ingalls Stevens recommended to the first territorial legislature a memorial to Congress for the grant of two townships of land for the endowment for a university. (“That every youth, however limited his opportunities, find his place in the school, the college, the university, if God has given him the necessary gifts.” Governor Stevens) March 22, 1854 Memorial to Congress passed by the legislature. January 29, 1855 Legislature established two universities, one in Lewis County and one in Seattle. January 30, 1858 Legislature repealed act of 1855 and located one university at Cowlitz Farm Prairies, Lewis County, provided one hundred and sixty acres be locally donated for a campus. (The condition was never met.) 1860 to 1869 December 12, 1860 Legislature passed bill relocating the university at Seattle on condition ten acres be donated for a suitable campus. January 21, 1861 Legislative act was passed providing for the selection and location of endowment lands reserved for university purposes, and for the appointment of commissioners for the selection of a site for the territorial university. February 22, 1861 Commissioners first met. “Father” Daniel Bagley was chosen president of the board April 16, 1861 Arthur A. Denny, Edward Lander, and Charles C. Terry deeded the necessary ten acres for the campus. (This campus was occupied be the University until 1894.) May 21, 1861 Corner stone of first territorial University building was laid. “The finest educational structure in Pacific Northwest.” November 4, 1861 The University opened, with Asa Shinn Mercer as temporary head. Accommodations: one room and thirty students. -

“I Woke up to the World”: Politicizing Blackness and Multiracial Identity Through Activism

“I woke up to the world”: Politicizing Blackness and Multiracial Identity Through Activism by Angelica Celeste Loblack A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Hordge-Freeman, Ph.D. Beatriz Padilla, Ph.D. Jennifer Sims, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 3, 2020 Keywords: family, higher education, involvement, racialization, racial socialization Copyright © 2020, Angelica Celeste Loblack TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ............................................................................................................................ iii Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction: Falling in Love with my Blackness ........................................................................ 1 Black while Multiracial: Mapping Coalitions and Divisions ............................................ 5 Chapter One: Literature Review .................................................................................................. 8 Multiracial Utopianism: (Multi)racialization in a Colorblind Era ..................................... 8 I Am, Because: Multiracial Pre-College Racial Socialization ......................................... 11 The Blacker the Berry: Racialization and Racial Fluidity ............................................... 15 Racialized Bodies: (Mono)racism -

A Critical Analysis of African-Centered Psychology: from Ism to Praxis

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 35 Issue 1 Article 9 1-1-2016 A Critical Analysis of African-Centered Psychology: From Ism to Praxis A. Ebede-Ndi California Institute of Integral Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, Religion Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Ebede-Ndi, A. (2016). A critical analysis of African-centered psychology: From ism to praxis. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 35 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2016.35.1.65 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Special Topic Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Critical Analysis of African-Centered Psychology: From Ism to Praxis A. Ebede-Ndi California Institute of Integral Studies San Francisco, CA, USA The purpose of this article is to critically evaluate what is perceived as shortcomings in the scholarly field of African-centered psychology and mode of transcendence, specifically in terms of the existence of an African identity. A great number of scholars advocate a total embrace of a universal African identity that unites Africans in the diaspora and those on the continent and that can be used as a remedy to a Eurocentric domination of psychology at the detriment of Black communities’ specific needs. -

Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X Talk It out 17

Writing for Understanding ACTIVITY Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X Talk It Out 17 Overview Materials This Writing for Understanding activity allows students to learn about and write • Transparency 17A a fictional dialogue reflecting the differing viewpoints of Martin Luther King Jr. • Student Handouts and Malcolm X on the methods African Americans should use to achieve equal 17 A –17C rights. Students study written information about either Martin Luther King Jr. • Information Master or Malcolm X and then compare the backgrounds and views of the two men. 17A Students then use what they have learned to assume the roles of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X and debate methods for achieving African American equality. Afterward, students write a dialogue between the two men to reveal their differing viewpoints. Procedures at a Glance • Before class, decide how you will divide students into mixed-ability pairs. Use the diagram at right to determine where they should sit. • In class, tell students that they will write a dialogue reflecting the differing viewpoints of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X on the methods African Americans should use to achieve equal rights. • Divide the class into two groups—one representing each man. Explain that pairs will become “experts” on either Martin Luther King Jr. or Malcolm X. Direct students to move into their correct places. • Give pairs a copy of the appropriate Student Handout 17A. Have them read the information and discuss the “stop and discuss” questions. • Next, place each pair from the King group with a pair from the Malcolm X group. -

The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillm

“A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By: Thomas Anthony Gass, M.A. Department of History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Advisor Dr. Kevin Boyle Dr. Curtis Austin 1 Copyright by Thomas Anthony Gass 2014 2 Abstract “A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975” traces the history and activities of the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from its revitalization during the Great Depression to the end of the Black Power Movement. The dissertation examines the NAACP’s efforts to eliminate racial discrimination and segregation in a city and state that was “neither North nor South” while carrying out the national directives of the parent body. In doing so, its ideas, tactics, strategies, and methods influenced the growth of the national civil rights movement. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the Jackson, Mitchell, and Murphy families and the countless number of African Americans and their white allies throughout Baltimore and Maryland that strove to make “The Free State” live up to its moniker. It is also dedicated to family members who have passed on but left their mark on this work and myself. They are my grandparents, Lucious and Mattie Gass, Barbara Johns Powell, William “Billy” Spencer, and Cynthia L. “Bunny” Jones. This victory is theirs as well. iii Acknowledgements This dissertation has certainly been a long time coming.