Modern, Modernity, Modernism: the Shaping of Brazil's Soul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feb. 7 to Apr. 30, 2017 Great Hall

Ministry of Culture and Museu de Arte To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Moderna de São Paulo present exhibition that inaugurated Brazilian modernism, Anita Malfatti: 100 Years of Modern Art gathers at FEB. 7 MAM’s Great Hall about seventy different works covering the path of one of the main names in TO Brazilian art in the 20th century. Anita Malfatti’s exhibition in 1917 was crucial to the emergence of the group who would champion modern art in Brazil, so much so that APR. 30, critic Paulo Mendes de Almeida considered her as the “most historically critical character in the 2017 1922 movement.” Regina Teixeira de Barros’ curatorial work reveals an artist who is sensitive to trends and discussions in the first half of the 20th century, mindful of her status and her choices. This exhibition at MAM recovers drawings and paintings by Malfatti, divided into three moments in her path: her initial years that consecrated her as “trigger of Brazilian modernism”; the time she spent training in Paris and her naturalist production; and, finally, her paintings with folk themes. With essays by Regina Teixeira de Barros and GREAT Ana Paula Simioni, this edition of Moderno MAM Extra is an invitation for the public to get to know HALL this great artist’s choices. Have a good read! MASTER SPONSORSHIP SPONSORSHIP CURATED BY REALIZATION REGINA TEIXEIRA DE BARROS One hundred years have gone by since the 3 03 ANITA Exposição de pintura moderna Anita Malfatti [Anita Malfatti Modern Painting Exhibition] would forever CON- MALFATTI, change the path of art history in Brazil. -

The Primitivist Critique of Modernity: Carl Einstein and Walter Benjamin1

The Primitivist Critique of Modernity: Carl Einstein and Walter Benjamin1 David Pan In the “Sirens” episode in Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus, relying on nothing more than the wax in his sailors’ ears and the rope binding him to the mast of his ship, was able to hear the sirens’ song without being drawn to his death like all the sailors before him.2 Franz Kafka, finally giving the sirens their due, points out that their song could certainly pierce wax and would lead a man to burst all bonds. Instead of attributing Odysseus’ sur- vival to his cunning use of technical means, which he calls “childish mea- sures,”3 Kafka attributes it to the sirens’ use of an even more horrible weapon than their song: their silence. Believing his trick had worked, Odysseus did not hear their silence, but imagined he heard the sound of their singing, for no one could resist “the feeling of having triumphed over them by one’s own strength, and the consequent exaltation that bears down everything before it.”4 The sirens disappeared from Odysseus’per- ceptions, which were focused entirely on himself. Kafka concludes: “If the sirens had possessed consciousness, they would have been annihilated at that moment. But they remained as they had been; all that had hap- pened was that Odysseus had escaped them.”5 Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno have argued that this ancient 1. From Primitive Renaissance: Rethinking German Expressionism by David Pan. Copyright 2001 by the University of Nebraska Press. 2. Homer, Odyssey, Book 12, pp.166-200. 3. -

Metamodernism, Or Exploring the Afterlife of Postmodernism

“We’re Lost Without Connection”: Metamodernism, or Exploring the Afterlife of Postmodernism MA Thesis Faculty of Humanities Media Studies MA Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Giada Camerra S2103540 Media Studies: Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Leiden, 14-06-2020 Supervisor: Dr. M.J.A. Kasten Second reader: Dr.Y. Horsman Master thesis submitted in accordance with the regulations of Leiden University 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 1: Discussing postmodernism ........................................................................................ 10 1.1 Postmodernism: theories, receptions and the crisis of representation ......................................... 10 1.2 Postmodernism: introduction to the crisis of representation ....................................................... 12 1.3 Postmodern aesthetics ................................................................................................................. 14 1.3.1 Sociocultural and economical premise ................................................................................. 14 1.3.2 Time, space and meaning ..................................................................................................... 15 1.3.3 Pastiche, parody and nostalgia ............................................................................................ -

Action Yes, 1(7): 1-17

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in . Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Bäckström, P. (2008) One Earth, Four or Five Words: The Notion of ”Avant-Garde” Problematized Action Yes, 1(7): 1-17 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-89603 ACTION YES http://www.actionyes.org/issue7/backstrom/backstrom-printfriendl... s One Earth, Four or Five Words The Notion of 'Avant-Garde' Problematized by Per Bäckström L’art, expression de la Société, exprime, dans son essor le plus élevé, les tendances sociales les plus avancées; il est précurseur et révélateur. Or, pour savoir si l’art remplit dignement son rôle d’initiateur, si l’artiste est bien à l’avant-garde, il est nécessaire de savoir où va l’Humanité, quelle est la destinée de l’Espèce. [---] à côté de l’hymne au bonheur, le chant douloureux et désespéré. […] Étalez d’un pinceau brutal toutes les laideurs, toutes les tortures qui sont au fond de notre société. [1] Gabriel-Désiré Laverdant, 1845 Metaphors grow old, turn into dead metaphors, and finally become clichés. This succession seems to be inevitable – but on the other hand, poets have the power to return old clichés into words with a precise meaning. Accordingly, academic writers, too, need to carry out a similar operation with notions that are worn out by frequent use in everyday language. -

Pagu: a Arte No Feminino Como Performance De Si

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS MESTRADO INTERDISCIPLINAR EM PERFORMANCES CULTURAIS LUCIENNE DE ALMEIDA MACHADO PAGU: A ARTE NO FEMININO COMO PERFORMANCE DE SI GOIÂNIA, MARÇO DE 2018. UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS MESTRADO INTERDISCIPLINAR EM PERFORMANCES CULTURAIS LUCIENNE DE ALMEIDA MACHADO PAGU: A ARTE NO FEMININO COMO PERFORMANCE DE SI Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação Interdisciplinar em Performances Culturais, para obtenção do título de Mestra em Performances Culturais pela Universidade Federal de Goiás. Orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Sainy Coelho Borges Veloso. Co-orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Marcela Toledo França de Almeida. GOIÂNIA, MARÇO DE 2018. i ii iii Dedico este trabalho a quem sabe que a pele é fina diante da abertura do peito, que o coração a toca. Por quem sabe que é impossível viver por certos caminhos sem lutar e não brigar pela vida. Para quem entende que a paz e perdão não tem nada de silencioso quando já se viveu algumas guerras. E por quem vive como se sentisse o seu desaparecimento a cada dia, pois as flores não perdem a sua cor, apenas vivem o suficiente para não desbotar. iv AGRADECIMENTOS Não agradecerei neste trabalho a nomes específicos que me atravessaram na minha caminhada enquanto o escrevia, mas sim as experiências que passei a viver nesse período de tempo em que pela primeira vez me permite viver sem ser apenas agredida. Pelos dias que passei a cuidar de mim mesma. Pela minha caminhada em análise que me permitiu entender subjetivamente o que eu buscava quando coloquei essa temática como pesquisa a ser realizada. -

Redalyc.Sérgio Milliet: Críticas a Anita Malfatti

Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros ISSN: 0020-3874 [email protected] Universidade de São Paulo Brasil Gomes Cardoso, Renata Sérgio Milliet: Críticas a Anita Malfatti Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, núm. 63, abril, 2016, pp. 219-234 Universidade de São Paulo São Paulo, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=405645350012 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto Sérgio Milliet: Críticas a Anita Malfatti [ Sérgio Milliet: art criticism on Anita Malfatti Renata Gomes Cardoso¹ RESUMO • A pintura de Anita Malfatti foi co- Brasil. • PALAVRAS-CHAVE • Crítica de mentada por diversos escritores, destacando-se Arte; Sérgio Milliet; Anita Malfatti; Arte Mo- entre eles Mário de Andrade, amigo que sempre derna; Modernismo; Escola de Paris. • ABS- a defendeu no âmbito do modernismo no Bra- TRACT • Many authors have discussed Anita sil, em críticas publicadas ou em cartas. Além Malfatti’s paintings, notably Mário de Andra- de Mário de Andrade e de Oswald de Andrade, de, her close friend and art critic, who wrote outro escritor que avaliou a produção da artis- about her relevance for the Brazilian Modern ta foi Sérgio Milliet, figura muito significativa Art, through articles and letters. Besides Má- naquele contexto, tanto por ter contribuído rio de Andrade and Oswald de Andrade, ano- com artigos para diversos jornais e revistas, ther important author of this period was Sér- quanto por ter viabilizado o contato dos artis- gio Milliet, who promoted the small group of tas e escritores brasileiros com personalidades Brazilian artists and writers in the Parisian relevantes do ambiente cultural francês. -

Modernity, Modernism, and Fascism. a "Mazeway Resynthesis"

0RGHUQLW\PRGHUQLVPDQGIDVFLVP$PD]HZD\UHV\QWKHVLV 5RJHU*ULIILQ Modernism/modernity, Volume 15, Number 1, January 2008, pp. 9-24 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/mod.2008.0011 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mod/summary/v015/15.1griffin.html Access provided by Universitätsbibliothek Bern (1 Mar 2015 12:52 GMT) GRIFFIN / modernity, modernism, and fascism 9 Modernity, modernism, and fascism. A “mazeway resynthesis”1 Roger Griffin MODERNISM / modernity VOLUME FIFTEEN, NUMBER Fascism and modernism: finding the “big picture” ONE, PP 9–24. Researchers combing through back numbers of this journal © 2008 THE JOHNS HOPKINS in search of authoritative guidance to the relationship between UNIVERSITY PRESS modernity, modernism, and fascism could be forgiven for occa- sionally losing their bearings. In one of the earliest issues they will alight upon Emilio Gentile’s article tracing the paternity of early Fascism to the campaign for a “modernist national- ism” which was launched in the 1900s by Italian avant-garde artists and intellectuals fanatical about providing the catalyst to a national program of radical modernization.2 They will also come across the eloquent case made by Peter Fritzsche for the thesis that there was a distinctive “Nazi modern,” that the Third Roger Griffin is Reich embodied an extreme, uncompromising form of politi- Professor in Modern History at Oxford cal modernism, a ruthless bid to realize an alternative vision of Brookes University modernity whatever the human cost.3 But closer to the present (UK), and author of they will encounter Lutz Koepnik’s sustained argument that over 70 publications on the aesthetics of fascism reflected its aspiration “to subsume generic fascism, notably everything under the logic of a modern culture industry, hop- The Nature of Fascism ing to crush the emancipatory substance of modern life through (Pinter, 1991). -

Pushkin and the Futurists

1 A Stowaway on the Steamship of Modernity: Pushkin and the Futurists James Rann UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 Declaration I, James Rann, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Acknowledgements I owe a great debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Robin Aizlewood, who has been an inspirational discussion partner and an assiduous reader. Any errors in interpretation, argumentation or presentation are, however, my own. Many thanks must also go to numerous people who have read parts of this thesis, in various incarnations, and offered generous and insightful commentary. They include: Julian Graffy, Pamela Davidson, Seth Graham, Andreas Schönle, Alexandra Smith and Mark D. Steinberg. I am grateful to Chris Tapp for his willingness to lead me through certain aspects of Biblical exegesis, and to Robert Chandler and Robin Milner-Gulland for sharing their insights into Khlebnikov’s ‘Odinokii litsedei’ with me. I would also like to thank Julia, for her inspiration, kindness and support, and my parents, for everything. 4 Note on Conventions I have used the Library of Congress system of transliteration throughout, with the exception of the names of tsars and the cities Moscow and St Petersburg. References have been cited in accordance with the latest guidelines of the Modern Humanities Research Association. In the relevant chapters specific works have been referenced within the body of the text. They are as follows: Chapter One—Vladimir Markov, ed., Manifesty i programmy russkikh futuristov; Chapter Two—Velimir Khlebnikov, Sobranie sochinenii v shesti tomakh, ed. -

LEISURE PLACES and MODERNITY the Use and Meaning of Recreational Cottages in Norway and the USA

LEISURE PLACES AND MODERNITY The use and meaning of recreational cottages in Norway and the USA Daniel R. Williams and Bjom P Kaltenborn Williams, D. R., & Kaltellbom, B. P. (1999). Leisure places and modernity: The use and meaning of recreational cottages in Norway and the USA. In D. Crouch (Ed.), Leisure practices and geographic Itnowledge (pp. 214-230). London: Routledge. Introduction When we think of tourism we often dunk of travel to exotic destinations, but modernization has also dispersed and extended our network of relatives, friends, and acquaintances. Fewer people live out their lives in a single place or even a single region of their natal country. Modern forms of dwelling, working, and playing involve circulating through a geographically extended network of social relations and a multiplicity of widely dispersed places and regions. Much of the "postmodern" discourse on tourism leaves the impression that tourists seek out only the exotic, authentic "other" and experience every destination through a detached "gaze" that rarely engages the "real" (i.e., uncommodified) aspects of the place (MacCanneU. 1992, Selwyn 1996, Urry 1990). Contrary to images of "gazing" tourists on a pilgrimage for the authentic, much of modern tourism is rather ordinary and involves complex patterns of social and spatial interaction that cannot be neatly reduced to a shallow detached relation. Leisure/tourism is often less packaged, commodified, and colonial than contemporary academic renderings seem to permit. One widespread, but largely unexamined form of leisure travel involves the seemingly enigmatic practice of establishing and maintaining a second home (what we will generally refer to as cottaginl). -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Modernism and the Search for Roots

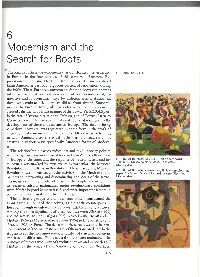

6 Modernism and the Search for Roots THE RADICAL artistic developments that transformed the visual arts 6. 1 Detail of Pl. 6.37. in Europe in the first decades of this century -Fauvism , Ex- pressionism , Cubism, D ada, Purism, Constructivism - entered Latin Ameri ca as part of a 'vigorous current of renovation' during the 1920s. These European movem ents did not, however, enter as intact or discrete styles, but were often adapted in individual, in novative and idiosyncratic ways by different artists. Almost all those who embraced M odernism did so from abroad. Some re mained in Europe; some, like Barradas with his 'vibrationism', created a distinct modernist m anner of their own [Pls 6.2,3,4,5] , or, in the case of Rivera in relation to Cubism , and of Torres-Garcfa to Constructivism, themselves contributed at crucial moments to the development of these m ovem ents in Europe. The fac t of being American, however, was registered in some form in the work of even the most convinced internationalists. Other artists returning to Latin Ameri ca after a relatively brief period abroad set about crea ting in various ways specifically America n forms of Modern ism . The relationship between radical art and revolut ionary politics was perhaps an even more crucial iss ue in Latin America than it was in Europe at the time; and the response of w riters, artists and in 6. 2 Rafa el Barradas, Study, 1911 , oil on cardboard, 46 x54 cm. , Museo Nacional de Arres Plasti cas, tellectuals was marked by two events in particular: the Mexican Montevideo. -

Influence and Cannibalism in the Works of Blaise Cendrars and Oswald De Andrade

Modernist Poetics between France and Brazil: Influence and Cannibalism in the Works of Blaise Cendrars and Oswald de Andrade Sarah Lazur Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 1 © 2019 Sarah Lazur All rights reserved 2 ABSTRACT Modernist Poetics between France and Brazil: Influence and Cannibalism in the Works of Blaise Cendrars and Oswald de Andrade Sarah Lazur This dissertation examines the collegial and collaborative relationship between the Swiss-French writer Blaise Cendrars and the Brazilian writer Oswald de Andrade in the 1920s as an exemplar of shifting literary influence in the international modernist moment and examines how each writer’s later accounts of the modernist period diminished the other’s influential role, in revisionist histories that shaped later scholarship. In analyzing a broad range of source texts, published poems, fiction and essays as well as personal correspondence and preparatory materials, I identify several areas of likely mutual influence or literary cannibalism that defied contemporaneous expectations for literary production from European cultural capitals or from the global south. I argue that these expectations are reinforced by historical circumstances, including political and economic crises and cultural nationalism, and by tracing the changes in the authors’ accounts, I give a fuller narrative that is lacking in studies approaching either of the authors in a monolingual context. 3 Table of Contents Abbreviations ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 – Foreign Paris 20 Chapter 2 – Primitivisms and Modernity 57 Chapter 3 – Collaboration and Cannibalism 83 Chapter 4 – Un vaste malentendu 121 Conclusion 166 Bibliography 170 i Abbreviations ABBC A Aventura Brasileira de Blaise Cendrars: Eulalio and Calil’s major anthology of articles, correspondence, essays, by all major participants in Brazilian modernism who interacted with Cendrars.