The Motion for New Trial Based on Inadequacy of Damages Awarded, 39 Neb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Trucking Associations V. Scheiner: Truckers Challenge Pennsylvania's Highway User Fees Under the Dormant Commerce Clause

University of Miami Law Review Volume 41 Number 5 Article 10 5-1-1987 American Trucking Associations v. Scheiner: Truckers Challenge Pennsylvania's Highway User Fees Under the Dormant Commerce Clause Robert J. Borrello Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Part of the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert J. Borrello, American Trucking Associations v. Scheiner: Truckers Challenge Pennsylvania's Highway User Fees Under the Dormant Commerce Clause, 41 U. Miami L. Rev. 1117 (1987) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol41/iss5/10 This Casenote is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CASENOTES American Trucking Associations v. Scheiner: Truckers Challenge Pennsylvania's Highway User Fees Under the Dormant Commerce Clause I. INTRODUCTION .. ....................................................... 1117 II. STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............................................... 1119 III. THE DORMANT COMMERCE CLAUSE ...................................... 1121 A. The Axle Tax Discriminatesin Effect ................................ 1122 B. The Complementary Tax Doctrine ................................... 1124 1. JUSTIFICATION FOR THE COMPLEMENTARY TAX: ONE-SIDED TAX BURDEN . -

Evansville-Vanderburgh Airport Authority Dist. V. Delta Airlines, Inc., 405 U.S

Florida State University Law Review Volume 1 Issue 2 Article 6 1973 Evansville-Vanderburgh Airport Authority Dist. v. Delta Airlines, Inc., 405 U.S. 707 (1972) Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Evansville-Vanderburgh Airport Authority Dist. v. Delta Airlines, Inc., 405 U.S. 707 (1972), 1 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 354 (1973) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol1/iss2/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FloridaState University Law Review [VOL 1 signals the judicial recognition in Florida of a valuable scientific de- vice which will aid in identifying the guilty while protecting the innocent.32 Constitutional Law - STATE TAXATION-AIRPORT USE TAXES IMPOSED ON DEPARTING COMMERCIAL AIRLINE PASSENGERS ONLY AS COMPEN- SATION FOR USE OF FACILITIES VIOLATE No FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS.-Evansville-Vanderburgh Airport Authority Dist. v. Delta Airlines, Inc., 405 U.S. 707 (1972). The rapid increase in private and commercial aviation operations' has necessitated concomitant airport development and expansion. One method of generating funds for these purposes is the so-called air- port use tax. Prior to 1972, only Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey and an Indiana airport authority district had actually imposed such taxes. 2 With slight variations, the tax in each instance took the printed. In such a situation the voiceprint could be excluded as the "fruit" of a con- stitutionally impermissible seizure. -

Recent Cases: Federal Jurisdiction. Erie Railroad Co. V. Tompkins

RECENT CASES in obtaining support if the husband remarries, since the second wife would be in a better position to get at the husband's assets. Apart from the formal adequacy of the wife's legal remedies, the injunction may nevertheless be necessary to protect the interest of the state in the marriage relation- ship.'9 Although New York courts would not give full faith and credit to the Florida decree, the validity of the decree in New York may never be litigated, for a wife who asks for an injunction may not be willing to bring a declaratory judgment action. In that case, the foreign decree would in effect dissolve the marriage. By deterring the husband from procuring the out-of-state divorce, the injunction serves to prevent the 2 state's interest from so being circumvented. 0 This consideration should be of para- mount importance in New York where the underlying domestic relations policy has been a strict enforcement of marital status, as evidenced by strict divorce laws and refusal to give full faith and credit to "Reno" divorces. Denial of an injunction in the present case stands in marked contrast to this policy. Federal Jurisdiction-Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins---"Federal Field" Doctrine- [Federal].-In a suit by an employee against an interstate railroad for back pay, the Supreme Court of Mississippi held that the cause of action was based upon the collec- tive agreement between the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen and the railroad, rather than upon the oral contract of employment between the plaintiff employee and the defendant; and that therefore the six-year state statute of limitations was ap- plicable.' Following the remand of the case for trial, plaintiff amended his pleadings so that an amount of more than $3000 was involved, whereupon defendant secured a removal to a federal court. -

CPY Document

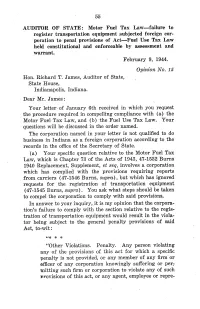

55 AUDITOR OF STATE: Motor Fuel Tax Law-failure to regster transporttion equipment subjected foreign cor- poration to penal provisions of Act-Fuel Use Tax Law held constitutional and enforceable by assment and warrt. February 9, 1944. Opinion No. 15 Hon. Richard T. James, Auditor of State, State House, Indianapolis, Indiana. Dear Mr. James: Your letter. of January 6th received in which you request the procedure required in compellng compliance with (a) the Motor Fuel Tax Law, and (b) the Fuel Use Tax Law. Your questions wil be discussed in the order named. The corporation named in your letter is not qualified to do business in Indiana as a foreign corporation according to the records in the offce of the Secretary of State. (a) Your specific question relative to the Motor Fuel Tax Law, which is Chapter 73 of the Acts of 1943, 47-1532 Burns. 1940 Replacement, Supplement, et seq, involves a corporation which has complied with the provisions requiring reports from carriers (47-1546 Burns, supra,), but which has ignored requests for the registration of transportation equipment (47-1545 Burns, supra). You ask what steps should be taken to compel the corporation to comply with said provisions. In answer to your inquiry,jt is my opinion that the corpora- tion's failure to comply with the section relative to the regis- tration of transportation equipment would result in the viola- tor being subject to the general penalty provisions of said Act, to-wit: "* * * "Other Violations. Penalty. Any person violating any of the provisions of this act for -

Recent Cases

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 26 Issue 1 Issue 1 - January 1973 Article 5 1-1973 Recent Cases Law Review Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Law Review Staff, Recent Cases, 26 Vanderbilt Law Review 139 (1973) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol26/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECENT CASES Antitrust-Horizontal Territorial Restraint-Allocation of Territories Among Members of Cooperative Purchasing Association Is Per Se Violative of Section 1 of the Sherman Act The United States brought suit to enjoin the activities of defendant, a cooperative buying association of small and medium-sized regional supermarket chains,' as unlawful under section 1 of the Sherman Act.2 Defendant obtained merchandise under private label so that member chains, which were allocated exclusive territories3 in which to sell the association's brands, could compete with national and regional chains possessing sufficient economic power to finance their own private label programs.4 The government contended that the horizontal restraints' I. "Topco is a cooperative association of approximately 25 small and medium-sized regional supermarket chains which operate stores in some 33 states. Each of the member-chains operates independently, there is no pooling of earnings, profits, capital, management or advertising re- sources. -

A Requiem for the Sudden Emergency Doctrine - Knapp V

Mississippi College Law Review Volume 2 Issue 3 Article 6 6-1-1981 Torts - A Requiem for the Sudden Emergency Doctrine - Knapp v. Stanford Timothy Lee Murr Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.law.mc.edu/lawreview Custom Citation 2 Miss. C. L. Rev. 305 (1980-1982) This Case Note is brought to you for free and open access by MC Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mississippi College Law Review by an authorized editor of MC Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TORTS-A REQUIEM FOR THE SUDDEN EMERGENCY DOCTRINE-Knapp v. Staqford, 392 So. 2d 196 (Miss. 1980). On December 31, 1977, at eleven o'clock p.m., a one vehi- cle auto accident occurred in which James Stanford was the owner and operator of the automobile. The passenger, Robert Knapp, sustained serious personal injuries. The accident hap- pened as the vehicle approached a sweeping left curve. The vehicle's right wheel left the pavement's right edge and slid onto the shoulder for approximately three or four seconds. Without braking, Stanford attempted to bring the vehicle back onto the hard surfaced road, which was six to eight inches above the shoulder due to recent road construction. The right wheels hung on the raised edge and caused the driver to lose control. The vehicle went into a spin, crossed the highway, turned over two or three times and came to rest in a ditch on the left side of the highway.1 While the resulting injuries to Robert Knapp were not disputed, the parties differed as to the cause of the accident.2 At trial for the recovery of Knapp's personal injuries, Stan- ford requested and was granted a jury instruction commonly referred to as the "sudden emergency" instruction.3 The jury 1. -

1939 Journal

— — I OCTOBEE TEEM, 1939 STATISTICS Original Appellate Total Number of cases on docket _ _ 15 1, 063 1, 078 Cases disposed of __ 4 942 946 Remaining on docket 11 121 132 Cases disposed of By written opinions 151 By per curiam opinions 97 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 690 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation 8 Number of written opinions 137 Number of admissions to bar 1,016 REFERENCE INDEX Page. Butler, J., death of, announced 73 Butler, J., resolutions of the Bar presented by Attorney Gen- eral Jackson 242 Murphy, J., commission read and oath taken (February 5, 1940) . 146 Eobert H. Jackson, Attorney General, presented his Commis- sion 126 Francis Biddle, Solicitor General, presented 126 Proceedings commemorating 150th Anniversary of Court (February 1, 1940) 136 Address of Attorney General Jackson 136 Address of Charles A. Beardsley, President of American Bar Association 139 Address of the Chief Justice 141 Advisory Committee requested to submit amendments to Eules of Civil Procedure 54 Administrative Office of United States Courts Henry P. Chandler appointed Director 75 Elmore Whitehurst appointed Assistant Director 54 Transfer of appropriations 54,221 Allotment of Justices 158 181208—40 98 — II Page. Disbarment, In the matter of Clyde H. Walker 34 Anna L. Cooke 34,81 David B. Getz 35,81 Walter C. Balderston 46 French B. Loveland (failure to reply to Clerk's communi- cations) 81, 109, 115 Rules of Supreme Court—Rule 41 amended 192 Regulations prescribed in reference to appeals from Court of Claims appearing in 210 U. S. -

JOHN T. HENDRICK, Plff. in Err., V. STATE of MARYLAND

Hendrick v. State of Maryland, 235 U.S. 610 (1915) 35 S.Ct. 140, 59 L.Ed. 385 Requirements of Laws Md.1910, c. 207, for registering automobiles at a cost varying KeyCite Yellow Flag - Negative Treatment according to the horse power, and for the driver Declined to Extend by County of Fond du Lac v. Derksen, Wis.App., May to obtain a license, and that nonresidents, to 29, 2002 have a limited use of the highways without cost, 35 S.Ct. 140 must have complied with a similar law in their Supreme Court of the United States. respective states and have secured a tag, are not unreasonable as to vehicles moving in interstate JOHN T. HENDRICK, Plff. in Err., commerce. v. STATE OF MARYLAND. 233 Cases that cite this headnote No. 77. [3] Commerce Motor Vehicles and Carriers | 83 Commerce Argued November 11 and 12, 1914. 83II Application to Particular Subjects and | Methods of Regulation Decided January 5, 1915. 83II(E) Licenses and Taxes 83k63 Licenses and Privilege Taxes Synopsis 83k63.15 Motor Vehicles and Carriers IN ERROR to the Circuit Court of Prince George's County, Rights of citizens to pass through the several State of Maryland, to review a conviction for violating the states held not unconstitutionally interfered with state motor vehicle law. Affirmed. by Laws Md.1910, c. 207, § 140a, relating to use of highways of the state by nonresident owners The facts are stated in the opinion. of automobiles. 69 Cases that cite this headnote West Headnotes (5) [4] Constitutional Law Discrimination in General [1] Commerce Nonexercise of Power by 92 Constitutional -

The Development of a Congressional Program Dealing with State Taxation of Interstate Commerce

Fordham Law Review Volume 36 Issue 3 Article 1 1968 The Development of a Congressional Program Dealing with State Taxation of Interstate Commerce Emanuel Celler Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Emanuel Celler, The Development of a Congressional Program Dealing with State Taxation of Interstate Commerce, 36 Fordham L. Rev. 385 (1968). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol36/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Development of a Congressional Program Dealing with State Taxation of Interstate Commerce Cover Page Footnote United States Representative from Tenth District of New York; member of the New York Bar. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol36/iss3/1 THE DEVELOPMENT OF A CONGRESSIONAL PROGRAM DEALING WITH STATE TAXATION OF INTERSTATE COMMERCE EMANUEL CELLER* I. BACKGROUND pROMINENT on the list of great legacies which modern America re- ceived from the original framers of the Constitution is the principle of a national common market. It is this principle-the principle of the Com- merce Clause-that has bound our states together in the economic union which is so essential to their political union. At the same time, this prin- ciple has also played a major role in the phenomenal development of our American economy. -

SS025.Mp3 Bill Thomas‐ Spurts and Starts 20 Minutes at a Time

SS025.mp3 Bill Thomas‐ Spurts and starts 20 minutes at a time. We have done about 80 of these tapes. Frank Miles‐ You have done about what? Bill Thomas‐ 80 of the tapes, 85 of the tapes. Frank Miles‐ Is that right? Bill Thomas‐ And what is going to happen is eventually the tapes will go over to Memphis State to the art History department (Tape Cuts) David Yellin‐ This is September 14th 1968 and we are at Frank Miles House interviewing Mr. Miles. Joan Beifuss and David Yellin. This is tape 1. Bill Thomas‐ Ok, Mr. Miles can you tell us a little about your background, where you were born, went to school that type of thing. Frank Miles‐ I was born in the middle part of Nebraska out in what they call the sandhill country. I spent the better part of my life there, I finally grew up there until I was 25 years old in Omaha Nebraska. Went to school at a number of peroquial school around Nebraska, because my mother died when I was about 5 years old. So I moved around a good bit until I wound up going to Craig University High School. I completed what we called classical course at craigmont university high school. I did not go on to college, this was in 1931. David Yellin‐ Of course it is interesting that you mention that and it falls in line why you didn’t, but a lot of young people wouldn’t know what you are talking about. Frank Miles‐ They wouldn’t know about the depression you mean? Yeah, that is a strange thing. -

State and Local Taxation: When Will Congress Intervene?

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications 1997 State and Local Taxation: When Will Congress Intervene? Kathryn L. Moore University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Taxation-State and Local Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kathryn L. Moore, State and Local Taxation: When Will Congress Intervene?, 23 J. Legis. 171 (1997). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. State and Local Taxation: When Will Congress Intervene? Notes/Citation Information Journal of Legislation, Vol. 23, No. 2 (1997), pp. 171-213 This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/476 ARTICLES STATE AND LOCAL TAXATION: WHEN WILL CONGRESS INTERVENE? Kathryn L. Moore* I. INTRODUCTION Our current system of fiscal federalism grants each of the fifty states plus the District of Columbia autonomy to design its own taxing system. Although this system has its advantages, it imposes an extraordinary burden on the interstate taxpayer, and few outside academia dispute that more uniformity is needed in state and local taxation of interstate and foreign commerce.' In theory, uniformity could be achieved in one of three ways: (1) by the United States Supreme Court's interpretation of the dormant Commerce Clause; (2) by the voluntary, joint action of the states; or (3) by congressional action. -

Tennessee State Library and Archives TENNESSEE STATE BOARD OF

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 TENNESSEE STATE BOARD OF EQUALIZATION RECORDS, 1897-1934 RECORD GROUP 43 Processed by: Archival Technical Services SCOPE AND CONTENT Records of the Tennessee State Board of Equalization encompass the period of 1897- 1934 and consist of realty assessment appeals of private individuals, banks, corporations and public utilities, and correspondence, memoranda and minutes. The Board was created pursuant to Chapter 120, Public Acts of 1895, and was know as the State Board of Equalizers and Assessors. Chapter 5, Public Acts of the Extra Session of 1895, was to have abolished the newly-created Board, but an engrossing error prevented the abolishment until Chapter 7, Public Act of 1897. During the interim period of 1897-1919, the responsibility for providing assessment relief was vested in a State Board of Equalization composed of the constitutional officers, Secretary of State, Treasurer and Comptroller. These officers served on the Board ex-officio, or by virtue of the office. Establishment of a more formal State Board was not accomplished until the adoption of Section 12, Chapter 1, Public Acts of 1919. The early activities of this Board are well documented in the First Biennial Report, 1919-1920, although original records are not available until 1927. Assessment appeals provide most of the records, and the Depression years produced most of the appeals for relief from excessive local assessments. A source for information of the economic climate of the times is thus available. Records of the early Board of Equalizers are minute books recorded between 1897 and 1907, several appeals in Polk County, and a Giles County Questionnaire in 1900.